While No One Was Looking: America, Guyana, and Venezuela

The border dispute that the US is exploiting and manipulating

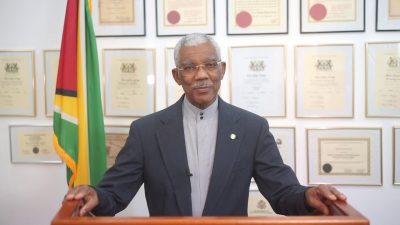

On March 2, 2020, the people of Guyana went to the polls. According to the Carter Center, at first things went really well. And then they didn’t. At the close of the day, President David Granger had been re-elected. But, though nine of ten districts reported cleanly, the largest district was mired in confusion. And the promise became chaos.

As the Granger government and Irfaan Ali’s opposition convicted each other of fraud and accused each other of coups, the battle between throwing out the election and recounting the large district four ended with a recount. And the recount reversed the decision. Granger was pressured to hand over power to Irfaan Ali.

The US was a leading voice in the call for a recount and the US applied a great deal of pressure on Granger to hand over the office of President. Two weeks after the initial count, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo warned Granger not to form an “illegitimate government” based on “electoral fraud” or he would “be subjected to a variety of serious consequences from the United States Government.” Then, on July 15, five weeks after the June 7 recount was completed, Pompeo announced “visa restrictions on individuals who have been responsible for, or complicit in, undermining democracy in Guyana.”

After undermining democracy, declaring fair elections frauds and supporting coups in Bolivia and Venezuela, why is America so concerned about fair elections in Guyana?

Like what really happened in the election, the answer is not clear. But what is clear is that Irfaan Ali now holds the Presidential office in Guyana. And, now in office, Ali has agreed to hold joint maritime patrols near waters that are importantly contested with Venezuela. In his joint announcement with Irfaan Ali, Pompeo referred to “Greater security, greater capacity to understand your border space, what’s happening inside your Exclusive Economic Zone” as “things that give Guyana sovereignty.”

Ali’s willingness to cooperate with the US, who is actively and aggressively pressing for regime change in Guyana’s neighboring Venezuela, is in sharp contrast to Granger’s reluctance. Granger rejected a request that came just after the March election from Voice of America for permission to use Guyana to broadcast into Venezuela. Just after the new election results, Ali agreed to partner with America against Venezuela. Granger’s campaign manager suggested that the Guyanese election “seem no longer to be about the Guyanese people but about other interests.”

Miguel Tinker Salas, Professor of Latin American History at Pomona College, and one of the world’s leading experts on Venezuelan history and politics, told me in a personal correspondence that “The US has been attempting to manipulate relations between Guyana and Venezuela, especially the long standing border dispute between both countries over the issue of the Essequibo which Venezuela has historically claimed.” He added the reminder that “Pompeo was recently in Guyana and Suriname to promote the US policy of isolating Venezuela.”

But, as Miguel Tinker Salas’ comment points out, the US has more than Venezuela in its sights. It also has its sights on the oil discoveries in the disputed waters of the Essequibo. As Miguel Tinker Sala told me, “Add to that oil, and the role of Exxon which is still smarting over their exit from Venezuela and you have the conditions which allow the US to exacerbate tensions between both countries.” But to understand the important role of oil in the US’s interference in the relationship between Guyana and Venezuela requires an understanding of two hundred years of history. And a half century of hypocrisy.

History

The border dispute that the US is exploiting and manipulating was born almost two centuries ago in 1835 when the British gently eased over the western borders of the Guyanese colony it had inherited from the Dutch and usurped a large portion of land from Venezuela.

In 1899, the matter of the disputed territory came up before an international tribunal. But the tribunal ruled in favor of Britain and granted British Guyana control over the disputed territory. Of course it did: the tribunal was stacked. Rather than being an impartial tribunal made up of Latin American countries as it should have been, the dispute was adjudicated by an international body dominated by the United States and – of all countries – Britain. Britain was hardly a disinterested party. Worst of all, Venezuela was not permitted a delegate to the tribunal! The Venezuelans were represented by former U.S. President Benjamin Harris.

“Needless to say,” Miguel Tinker Salas says in his book Venezuela: What Everyone Needs to Know, Venezuela’s “prospects of prevailing in a tribunal dominated by foreign powers appeared slim.” And slim it was. The tribunal, which was dominated by Britain and excluded Venezuela, ruled in favor of Britain and against Venezuela. The tribunal issued its decision without any supporting rationale. The ruling gave Britain possession of over 90% of the disputed territory it had stolen from Venezuela sixty-four years earlier.

Years later, it would be revealed that the tribunal was not only stacked, it was fixed. The official secretary of the American represented Venezuelan delegation to the international tribunal, Severo Mallet-Prevost, confirmed Venezuela’s allegation when he revealed in a posthumously published letter that the governments of Britain and Russia influenced the president of the tribunal to exert pressure on the arbitrators to rule in Britain’s favor.

That letter was not published until 1949. Seventeen years later, in 1966, citing the corruption that usurped the territory that was rightfully theirs, Venezuela claimed the territory at the United Nations. At that time, Venezuela, Guyana and Britain signed the Treaty of Geneva, agreeing to resolve the dispute and promising that neither Venezuela nor Guyana would do anything on the disputed territory until a border settlement had been arrived at that was acceptable to all.

That treaty is violated by Pompeo’s agreement with Ali to hold joint maritime patrols that reinforce Guyana’s “security”, “border space”, “Exclusive Economic Zone” and “sovereignty,” in the words of Mike Pompeo.

But this is not the first time. As Miguel Tinker Salas said, Exxon “is still smarting over their exit from Venezuela” in the Hugo Chavez years. So, despite the Treaty of Geneva, Guyana has begun extracting oil in the disputed territory. In 2015, ExxonMobil made a huge oil discovery in the very waters disputed by Guyana and Venezuela. In order to get around the laws enacted by Chavez that nationalized the oil and natural gas industries of Venezuela that had previously been controlled mostly by American oil interests, ExxonMobil and Guyana simply asserted that the oil was in Guyanese territory. That assertion was made in flagrant defiance of the Treaty of Geneva, which stipulated that neither country could act in that territory until the border had been resolved. America can now portray Venezuela as an aggressor, attempting to steal oil from its tiny, impoverished neighbor.

That flagrant violation has continued as ExxonMobil “ramps up crude output from Guyana’s massive” offshore oil reserves. ExxonMobil has been extracting and exporting this oil at least since December of 2019.

So, the US is concerned with Guyana as a tool for exerting pressure on Venezuela both for regime change and to steal back the oil that Chavez took back to use for his own people: oil reserves so large, they could now make Guyana one of the richest countries in the world.

Hypocrisy

There is also a historical hypocrisy to America using Guyana as a tool to bring about a coup against the left wing, nationalist government of Venezuela because Guyana just got over the effects of the American coup that brought down its left wing, nationalist government. Though the US is using Guyana to help bring down the government of Venezuela, documents just declassified in April of 2020 reveal clearly that in the first half of the 1960’s, Guyana was the Venezuela of its day.

Cheddi Jagan was the popularly elected Prime Minister of British Guyana. He had been elected by a large majority in 1953 and reelected in 1957 and 1961. But, by then, the Americans had had enough, and in 1962, the CIA undertook to organize and finance anti-Jagan protests: President Kennedy would use the CIA to remove Jagan in a coup.

For decades after the thirty year rule on classified documents had expired, the CIA and the State Department refused to declassify the documents on British Guyana. But now they have finally been declassified. As The New York Times reported on October 30, 1994, at the end of the thirty years, the then “Still-classified documents depict in unusual detail a direct order from the President to unseat Dr. Jagan, say Government officials familiar with the secret papers. . . . The Jagan papers are . . . a clear written record . . . of a President’s command to depose a Prime Minister.”

Jagan was a nationalist politician who considered himself a socialist. A 1962 National Intelligence Analysis admitted that Jagan was not a communist and that his posture would probably be one of nonalignment. Nonetheless, the CIA feared that Jagan demonstrated susceptibility to being receptive of advice from communists; the NSA said he could become one. Later, US intelligence would call him a communist while admitting he was not under the sway of the Soviet Union. By the middle of 1962, Kennedy had told the British Prime Minister “that we simply cannot afford to see another Castro-type regime established in this Hemisphere. It follows that we should set as our objective an independent British Guiana under some other leader.” Kennedy called for a coup.

To achieve that goal, he would unleash a full spectrum political action to remove the democratically elected Jagan from power. So, the CIA set about changing the direction of Guyanese domestic affairs: it boosted Jagan’s opponents, engaged in propaganda, pushed against his popularity and tried to discredit him. The focus of the political action was the so called “General Strike” that began in April of 1963. The CIA advised union leaders on how to organize and sustain the strike and trained strikers. They provided strike pay for workers and food and funds to keep the strike going. They also provided money for propaganda on behalf of the strike. Is estimated that the CIA spent about $800,000, which today is the equivalent of around $6.7 million.

The CIA also created new parties that were positioned to bleed off Jagan supporters. They provided those parties with advisors and support. According to National Security Advisor McGeorge Bundy’s assistant, Gordon Chase, the CIA “in a deniable and discreet way” had begun financing party workers. US money paid for leaflets, campaign buttons and more. The CIA helped with slogans and campaign strategy. Labor operatives and some campaign workers had their salaries paid by the US. McGeorge Bundy even approved paramilitary training: just in case.

The coup de grâce of the coup was getting the British to amend the Guyanese constitution to transform the Guyanese political system into one of proportional representation. That change, it was expected, would work to gain opponents seats sufficient to deny Jagan another majority government.

Simultaneously with all of these political maneuvers, the States was crippling Guyana’s economy by closing markets to its exports, imposing an embargo and refusing to provide oil. The deprivation would force Jagan to turn increasingly to Cuba and the U.S.S.R, and old trick to allow the States to declare an opponent a communist.

Despite all of these actions, Jagan won the most votes – 47%, which was more than he won in the last election – and a plurality of the seats (24 out of 53). But the CIA’s political action succeeded in denying him his majority, and, in a blatant move, the British governor simply refused to allow Jagan his opportunity to put together a government and called on the second place finisher, CIA supported Forbes Burnham, to form the government.

Burnham would go on to rule Guyana as a corrupt dictator until his death, ending democracy in Guyana until 1992, when, in its first free election since the coup, the Guyanese elected . . . Cheddi Jagan.

In 1990, Kennedy advisor Arthur Schlesinger publicly apologized to Cheddi Jagan and admitted that it was his recommendation that got the British to make the constitutional change to proportional representation that cost Jagan his government.

So, the US interference in, and manipulation of, the relationship between Guyana and Venezuela is long on history and hypocrisy that needs to be remembered in understanding the events of today being maneuvered by Mike Pompeo in the contested waters near Venezuela.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Ted Snider has a graduate degree in philosophy and writes on analyzing patterns in US foreign policy and history.