African Emigration and the United States Civil War

Through flight and rebellion enslaved people created the conditions for their own liberation

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Donation Drive: Global Research Is Committed to the “Unspoken Truth”

***

After the United States Congress outlawed participation in the Atlantic Slave Trade in 1808, the kidnapping and importation of Africans into North America continued. (See this)

From the geographical regions on the continent where the trade in human capital thrived, there was resistance from Africans to their bondage which was designed for the purpose of gross exploitation enforced through national oppression.

Numerous revolts among the enslaved African population occurred throughout the Western Hemisphere from Brazil, St. Vincent, Jamaica, Haiti, Cuba, the United States, among others. In the U.S., the plans for rebellion in Richmond led by Gabriel in 1800; the German Coast revolt in Louisiana in 1811; the Charleston incident under the direction of Denmark Vessey in 1822; a widespread revolt in 1831 led by Nat Turner in Southhampton County, Virginia shook the ideological foundations of the slavocracy.

These acts of resistance were the most well known since under the system of African enslavement there was resistance which took many forms on a daily basis. In addition to direct violent confrontation with the slave owners and their functionaries, many people fled the plantations seeking freedom from the tyranny of enforced labor exploitation.

Those Africans who escaped bondage either through legal means after the conclusion of the Revolutionary War in the northeast or migration to areas outside the U.S., played a critical role in the establishment of the Underground Railroad. This term was attributed to an organized cadre of anti-slavery activists who facilitated the departure of Africans from their slave masters.

In areas within the northeast of the U.S. there were newspapers founded in cities such as New York, Philadelphia and Boston which advocated the emancipation of African people. In Philadelphia there was the formation of anti-slavery societies for both men and women. Philadelphia was the scene of the initiation of the Free African Society and later the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) which contributed to the political education and agitation for the dissolution of legalized slavery. (See this)

Mary Ann Shadd and the Debates Surrounding Emigration and Full Equality

One of the key routes of the Underground Railroad was pathed through 19th century Detroit where a community of African Americans by the 1830s-1840s began to build independent institutions in this strategically located municipality bordering what became known as Ontario, Canada. One of the first urban rebellions in the U.S. took place in Detroit in 1833 when a couple which fled from enslavement in Kentucky were jailed in efforts to send them back into bondage.

The plight of Thornton and Lucie Blackburn prompted the African American community in Detroit at the time to forcefully liberate the couple and arrange transport to Canada. After 1833, the British-controlled territories were declared free from slavery. The Blackburns later took up residence in Toronto where they became a self-sufficient couple operating their own transportation business in the city.

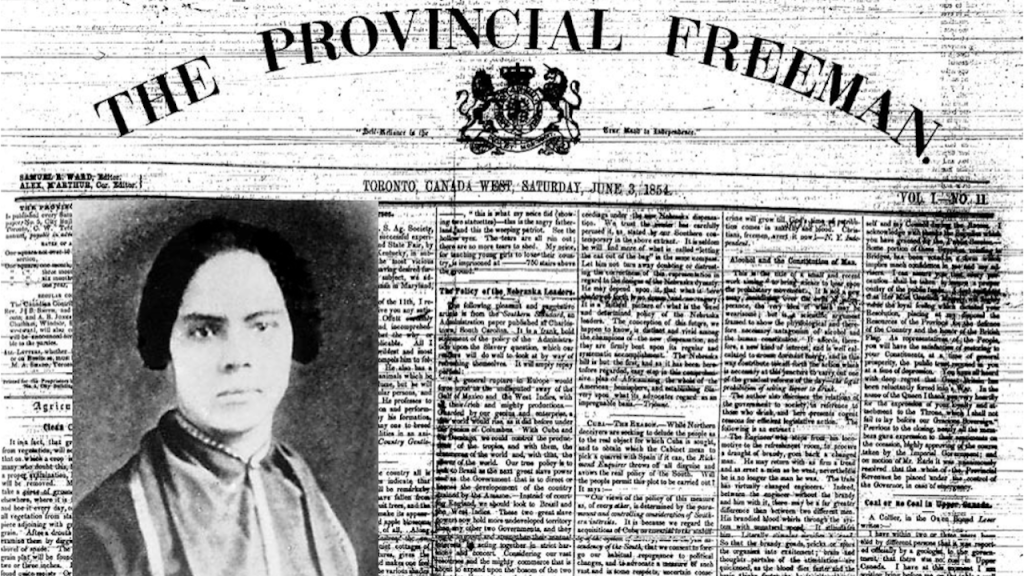

In later years, Mary Ann Shadd Cary represented a prime example of the role of African people in Ontario during the period of the mid-to-late 19th century. Shadd became a journalist, publishing the Provincial Freeman which advocated the abolition of slavery as well as African emigration from areas where they were endangered of being placed in bondage.

One source on the political organizing work being done during this period points out:

“In 1823, Mary Ann Shadd was born in Delaware to a free couple. Shadd is recognized today as the first Black female editor in the United States and, after emigrating as an adult, one of the first female journalists in Canada. After the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Shadd and one of her brothers left the U.S. to move to Canada. Encouraged by Henry and Mary Bibb—two active attendants at the 1854 Emigration Convention—Shadd later became a teacher. After doing so, she successfully established a school for Black children and, in 1852, published several pro-emigration booklets. One of her most well-known pieces is titled A Plea for Emigration: or Notes of Canada West, which encouraged her Black readers to emigrate to Canada. The year before, Shadd has been the only woman present at the first Convention of Colored Freemen.”

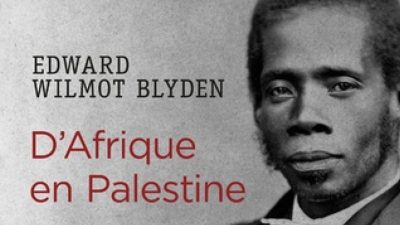

These developments were by no means isolated. Others advocated a return to the African continent such as Edward Wilmot Blyden (1832-1912) who eventually moved to Liberia and Sierra Leone while working for many years as a journalist, educator, diplomat and politician. The Republic of Liberia was established formally in 1847. Nonetheless, the American Colonization Society (ACS) remained controversial among Africans in the U.S. during the antebellum period. (Edward Wilmot Blyden (1832-1912) (blackpast.org))

Due to the prevalence of institutional racism, many whites believed that African Americans legally manumitted from enslavement could not live a productive existence in the U.S. Earlier Sierra Leone, also in West Africa, was established after the conclusion of the Revolutionary War for those who fought alongside the British who had promised freedom in the aftermath of the conflict.

However, the experiences of Shadd Cary embodied the contradictions and rigorous debate among the African American people. This same above-mentioned document emphasized:

“Much like her father, who edited the Liberator alongside William Lloyd Garrison, Shadd was inspired to create her own newspaper in order to pursue her pro-emigration and abolitionist goals. She did just that, publishing the first issue of Provincial Freeman on March 25, 1854. Shadd did not place her name under the masthead of the paper, ‘thus concealing the paper’s editorship.’ In addition to including her own articles (without crediting herself) in the paper, Shadd incorporated the work of other influential abolitionists and pro-emigrationists such as Martin Delany. Although Mary Ann Shadd was not in attendance at the 1854 Emigration Convention, it can be said that her pro-emigration pieces in the Provincial Freeman were incredibly influential as associated textual pieces engaging the convention event. The following year, Shadd maneuvered her way into the 1855 Colored Convention. Although her emigration ideas clashed with some delegates, Shadd presented a speech at the convention. It proved convincing to the delegates so much so that they granted permission to extend her speaking time.”

Nevertheless, when the Civil War erupted in the U.S. in 1861, Shadd and her husband, Thomas F. Cary, returned to the U.S. Shadd worked as a recruiting officer for the Union army encouraging African Americans to enlist to fight for the end of slavery. After the war, Shadd studied law and became one of the first women lawyers to practice in the U.S.

African Labor and the Civil War

At the beginning of the Civil War in April 1861, there were nearly 4.5 million Africans living in the U.S., 90 percent of whom were enslaved. The profits accrued from the theft of Indigenous land, the importation of enslaved African labor and its super-exploitation economically benefited the slavocracy and the burgeoning industrial capitalists largely based in the northern states.

The contradictions between the systems of slavery and industrial capitalism underlined the outbreak of the Civil War. The valuable enslaved labor of African people served as the basis for the prosperity and social status of the planters.

Dr. W.E.B. Du Bois during the Great Depression in 1935 published his seminal work entitled “Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880.” In the first chapter of this book, The Black Worker, Du Bois puts forward his thesis which emphasizes that the African agricultural proletariat played a central role in the defeat of the Confederacy.

Du Bois writes saying:

“It was thus the black worker, as founding stone of a new economic system in the nineteenth century and for the modern world, who brought civil war in America. He was its underlying cause, in spite of every effort to base the strife upon union and national power.”

After the Civil War and the failure of Federal Reconstruction by 1877, African Americans were thrust back into a social situation reminiscent of the antebellum period. It would take nearly another century to regain those rights granted through the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments to the Constitution as well as the Civil Rights Acts passed between 1866-1875.

Today in the third decade of the 21st century the right to the universal franchise, access to public accommodations and education remain contested in the U.S. Consequently, the issues which drove the country into a civil war could resurface threatening the very existence of the bourgeois democratic system which has developed since the latter decades of the previous century.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Abayomi Azikiwe is the editor of the Pan-African News Wire. He is a regular contributor to Global Research.

All images in this article are from the author