African Americans Still Subjected to National Oppression: 150 Years Since the Passage of the Fourteenth Amendment

Citizenship, equal protection, due process, privileges and immunities elude the descendants of former enslaved Africans well into the 21st century

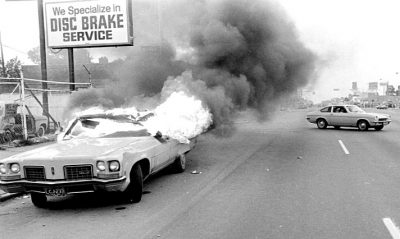

Featured image: Detroit Livernois Rebellion in 1975

After the conclusion of the United States Civil War and the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, the question of the social status of Africans was a subject of sharp debate and political struggle.

Even though the Fourteenth Amendment was approved by a vote of Congress in 1866 it would take another two years for the legislation to be ratified by three-fourth of the states within the reconstituted Union.

The Thirteenth Amendment which was adopted by both Houses of Congress on December 6, 1865, some eight months after the fall of the Confederate capital of Richmond, ostensibly gave Africans citizenship within the U.S. Prior to this constitutional addition, President Abraham Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862 which went into effect on January 1, 1863. This however, Lincoln even knew at the time, would not end slavery in all states after the end of the war.

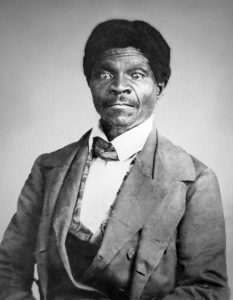

These legislative and administrative acts appeared to contradict the Supreme Court ruling in the Dred Scott Case (Dred Scott v. John F.A. Sandford), where it was ruled in March 1857, in a 7-2 decision that a formerly enslaved African (Dred Scott) who had lived in a non-slave owning state and territory was in any form covered under the constitutional rights guaranteed to whites. The case declared boldly that Africans are not and would never be citizens of the United States. It also reasoned that the Missouri Compromise (1820), which had designated free all territories west of Missouri and north of latitude 36°30′, was a violation of the U.S. Constitutional. (Source)

Even though the character of such a horrendous ruling is reprehensible, the reality of the decision is that it embodies the reality of the ongoing national oppressive conditions under which Africans in the U.S. continue to live. A host of court rulings and legislative acts and amendments have been passed since the advent of the Civil War and Reconstruction period right through to the post World War II Civil Rights era, however, Africans in the U.S. remain the subjects of discriminatory treatment, social containment and super-exploitation.

As stated in the Thirteenth Amendment, which reads that:

“Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

It later goes on to say in section two that Congress has the: “power to enforce” through the passage of “appropriate legislation.”

This notion which upholds that slavery is permissible if someone is convicted and sentenced for a crime is an important exception within section one since it is a social mechanism utilized in the 21st century to incarcerate large segments of the African American population. The disproportionate presence of the descendants of enslaved Africans within the correctional system is a clear manifestation of the failure of the U.S. Constitution to adequately address the guarantees of due process, citizenship along with privileges and immunities.

Nonetheless, even with the adoption of the Civil Rights Act of April 1866, the political and social rights of the former slaves and their offspring were by no means guaranteed. This bill with its ten sections grants full citizenship rights to the African people and authorizes the president, the courts and agents of the state to uphold the violation or attempts at denial of fundamental political rights to anyone inside the U.S. with the exception of Native Americans who are not taxed by the government.

(Source)

Despite this seemingly strong Act approved and signed by the Congress, it was still necessary to navigate the Fourteenth Amendment through the legislative branches at both the national and state levels. Nevertheless, the issues related to full equality and due process for African Americans remain unresolved.

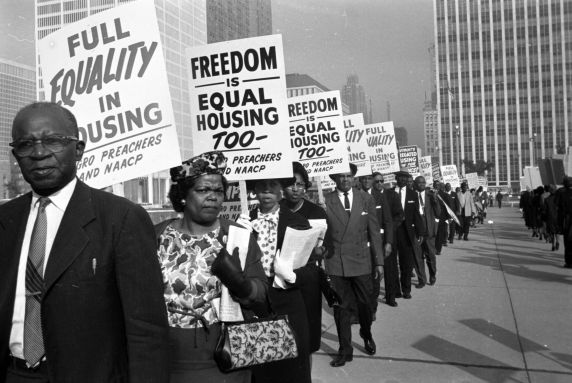

In addition to the disparate representation of African Americans in the criminal justice corporate complex, there is the higher rates of joblessness, employment status, poverty and the far less accumulation of household wealth. Although institutional racism was outlawed again during a second historical round of legislation beginning with the Civil Rights Acts 1957, 1964 along with the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and Fair Housing Act of 1968, these measures have not brought about either full equality for African Americans or their inherent right to self-determination.

Fair Housing Demonstration in the 1960s

Historic Opposition to the Legal Assumptions of the Fourteenth Amendment

Just five years after the ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court decision in the Slaughter-House Cases of 1873 limited the application of the privileges and immunities clause of the legislation. The ruling in this constitutional case set the stage for the evisceration of the Civil Rights of African Americans well into the middle of the following 20th century.

A review of the challenges to the Fourteenth Amendment, by the Constitutional Center website cites the Slaughter-House Cases decision to be the first significant erosion of the legislation which grew directly out the efforts to grant citizenship rights to African people in the U.S. Paralleling this decision was the growth of white terrorist organizations such as the Ku Klux Klan, the widespread existence of lynching, state and local legislative actions providing pseudo-legal covers for segregation known as Jim Crow, among other measures.

The entry by the Constitutional Center says:

“The Court said that the Privileges and Immunities Clause only prevented the federal government from abridging privileges and immunities guaranteed in the 14th Amendment and that the clause did not apply to the states. The move gutted the Privilege and Immunities Clause of its effect and kept the door open for Jim Crow laws in the South. To this day the Privileges and Immunities Clause is seldom invoked.”

Following the Slaughter-House Cases was of course the infamous Plessy v. Ferguson Decision in May of 1896, which was a challenge to the segregation of public accommodations in the state of Louisiana involving train stations. The racist state legislation in Louisiana was passed as a by-product of the federal government’s withdrawal of troops from the South and its abandonment of enforcement of the Fourteenth Amendment.

The state courts and the Supreme Court ruled against African American Homer Adolph Plessy saying that as long as the facilities are equal racial segregation was not unconstitutional. This was the legal standard within the Supreme Court until Brown v. Topeka was decided in May 1954 reversing Plessy v. Ferguson, declaring the legal basis for separate but equal as being without a doubt unconstitutional.

This 1954 ruling was used to forge ahead with the Civil Rights Movement aimed at abolishing all forms of legalized segregation whether in the realm of public life, labor markets and education funded by tax revenues. The cluster of Civil Rights legislation and federal court decisions facilitated the breaking down of institutional racism within the U.S. state.

The Reversal and Reinforcement of Racism and National Oppression

Even amid these apparent advances, the continued divisions resulting from economic exploitation and national oppression continued in the U.S. By the 1960s, African Americans and their allies engaged in mass demonstrations, boycotts, urban rebellions and electoral campaigns with the objective of achieving both full equality and self-determination.

The advent of affirmative action and quota systems of admission and advancement provided guidelines in the desegregation trajectory. These developments did not go without vigorous resistance from the racists and their agents within the government. By 1978, some 110 years after the advent of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Regents of the University of California v. Bakke resulted in the legal abrogation of any form of effective Affirmative Action on a national scale. A series of cases since then has weakened and even outlawed any form of guaranteeing the right of African Americans and other oppressed groups from participation in higher education and other sectors within the U.S. society.

Constitutional Center in its summary of the ruling notes of the Bakke Decision:

“The medical school set aside 16 spots for minority candidates in an attempt to address unfair minority exclusion from medical school. All 16 candidates from both years had test scores lower than Bakke’s but gained admission. Bakke contested that his exclusion from the Medical School was entirely the result of his race. The Supreme Court ruled in a severely fractured plurality that the university’s use of strict racial quotas was unconstitutional and ordered that the medical school admit Bakke, but it also said that race could be used as one of several factors in the admissions process. Justice Lewis F. Powell, Jr., cast the deciding vote ordering the medical school to admit Bakke. However, in his opinion, Powell said that the rigid use of racial quotas violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.”

Implications for the Way Forward in the 21st Century

Some forty years later this is the general atmosphere prevailing in the U.S. in regard to the legal and social status of African Americans. More than a decade ago beginning with the Great Recession of 2007-2010, over 50 percent of African American household wealth was stolen through the predatory lending and other aspects of the policies of finance capital. Much of this loss was a direct result of fraudulent mortgage lending (notwithstanding the Fair Housing Act of 1968), labor market restructuring and the denial of democratic rights through systems of emergency management.

Citing a report published by the National Association of Real Estate Brokers in 2013, the National Low Income Housing Coalition emphasizes:

“According to the report, African Americans have lost over half of their wealth since the beginning of the recession through falling homeownership rates and loss of jobs. Further, African American homeownership peaked in 2004, indicating that the housing crisis hit this community earlier than the nation as a whole. Since 2007, nearly 8 percent of African Americans and Latinos have lost their homes to foreclosure compared to 4.5 percent of non-Hispanic whites at similar income levels. The disparity ratio shows that African Americans are more than 70 percent more likely to have been foreclosed upon than non-Hispanic whites.”

Consequently, in order for any semblance of progress related to preserving and enhancing the household wealth, social equality, self-determination and independence of the African American people, there must be a struggle waged against finance capital. The radical redistribution of the overall wealth and economic power of the U.S. is a prerequisite for genuine social transformation and the elimination of national oppression and institutional racism.

*

All images in this article are from the author.