African Americans, National Liberation and the Vietnamese Revolution, Reject the Pentagon War Machine

Five decades ago global struggles against imperialism united peoples throughout the world

During the height of the genocidal war waged by the United States against the people of Vietnam during the 1960s and early 1970s, African Americans were involved in a life and death campaign aimed at reclaiming their national identity, human rights and racial dignity.

January 30 represented the fiftieth anniversary of the Tet Offensive which shook the foundation of the U.S. war strategy in Vietnam. In a surprise move, the forces of the National Liberation Front (NLF) and the People Army of Vietnam (PAVN) attacked over 100 cities and towns across the country.

Although the anti-war movement during this period is often portrayed as an effort initiated and led by white university students with left wing political leaning and that African Americans were almost exclusively pre-occupied with Civil Rights and Black Power demands within a domestic framework, the reality of the period proves to be quite to the contrary of such false assertions. From the early 1960s, leading figures within the Civil Rights and Black Nationalists movements expressed their opposition to the American role in Vietnam.

Moreover, the most advanced elements offered concrete acts of solidarity with the Democratic Republic of Vietnam in the North and the National Liberation Front (NLF) operating in the South which was occupied by the Pentagon. Both Vietnamese and the African American people were subjected to imperialism and national oppression by an enemy which sought to crush their respective entitlements to peace, social justice, self-determination and sovereignty.

In fact dating back to at least 1924, the man who became known as Ho Chi Minh (Nguyen Ai Quoc) had lived in upper Manhattan as an activist among the African American community during the period known as the Harlem Renaissance. Reports indicate that Ho had worked with the organization led by Marcus Garvey known as the Universal Negro Improvement Association—African Communities League (UNIA-ACL), headquartered in New York City at its zenith in the early 1920s.

Reflecting on his observations conducted just six decades after the conclusion of the U.S. Civil War and the legal dissolution of chattel slavery in a period of extreme state repression, widespread institutional racism and arbitrary violence, Ho published a pamphlet in 1924 labeled ”On Lynching and the Ku Klux Klan.” The work documents various aspects of social conditions prevailing in African American communities throughout the country.

Ho noted in this important work that:

“It is well-known that the Black race is the most oppressed and the most exploited of the human family. It is well-known that the spread of capitalism and the discovery of the New World had as an immediate result the rebirth of slavery. What everyone does not perhaps know is that after sixty-five years of so-called emancipation, American Negroes still endure atrocious moral and material sufferings, of which the most cruel and horrible is the custom of lynching.”

This same publication goes on to chronicle the history of racial terror against African people from the end of the war between the states over the future of slavery to the burgeoning resistance of the people in the aftermath of World War I. During the war and afterward, African Americans migrated in the millions to Northern, Midwestern and Western municipalities, becoming a social force in the struggle for freedom and democratic rights whose impact extended beyond their own population.

This same pamphlet emphasized the significance of this transformation saying:

“The victory of the Federal Government had just freed the Negroes and made them citizens. The agriculture of the South – deprived of its Black labor, was short of hands. Former landlords were exposed to ruin. The Klansmen proclaimed the principle of the supremacy of the white race. Anti-Negro was their only policy. The agrarian and slaveholding bourgeoisie saw in the Klan a useful agent, almost a savior. They gave it all the help in their power. The Klan’s methods ranged from intimidation to murder…. The Klan is for many reasons doomed to disappear. The Negroes, having learned during the war that they are a force if united, are no longer allowing their kinsmen to be beaten or murdered with impunity. They are replying to each attempt at violence by the Klan. In July 1919, in Washington, they stood up to the Klan and a wild mob. The battle raged in the capital for four days. In August, they fought for five days against the Klan and the mob in Chicago. Seven regiments were mobilized to restore order. In September the government was obliged to send federal troops to Omaha to put down similar strife. In various other states the Negroes defend themselves no less energetically.”

The Vietnamese Revolution and the Challenge to Western Imperialism

Ho left the U.S. traveling to other parts of the world including Europe. In 1930, the Indochinese Communist Party was formed encompassing revolutionaries from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia who were battling French colonialism. Later Vietnam was occupied by both Paris and Japan.

Consequently, the struggle for national liberation and unity took on an international character. After the defeat of Japan, the Democratic Republic of Vietnam was proclaimed in September 1945 prompting another guerrilla war against French imperialism. By 1954, France had been humiliated at the battle of Dien Bien Phu. Ho had become a hero within the international movement for independence and socialism.

Nonetheless, U.S. imperialism took over the war of domination from France and by the early 1960s President John F. Kennedy was deploying “advisors” in the form of military personnel in South Vietnam still under occupation. France and the U.S. refused to allow free elections and the war continued.

With specific reference to African American opposition to the Vietnam War and solidarity with the NLF and the government in Hanoi, Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam had been against the involvement of the U.S. since the early 1960s. After leaving the NOI, Malcolm X (El Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) adopted a decisively revolutionary position related to world revolution speaking frequently in solidarity with the People’s Republic of China and the Vietnamese Revolution.

One of the earliest developments in the Civil Rights Movement in the South related to Vietnam was a campaign by the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) in the summer of 1965 when a flyer and petition was circulated calling for African Americans to refuse induction into the military to fight in Vietnam since they were not given equal rights in the U.S. Later leaders of the MFDP clarified their stance after much adverse press attention saying that these views were not the official position of the MFDP. They did reiterate the rationale behind African American opposition to the war based upon the continuing problems of racism. (Source)

During the same year, Detroit activist General Gordon Baker, Jr. wrote a letter to the draft board articulating why he would reject induction. Baker stated to the board that:

“when the call is made to free the black delta areas of Mississippi, Alabama, South Carolina; when the call is made to FREE 12Th STREET HERE IN DETROIT, when these calls are made, send for me, for these shall be Historical Struggles in which it shall be an honor to serve!”

By early January 1966, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) issued an official statement opposing the war and the draft. This intervention took place in the immediate aftermath of the racist murder of SNCC member Sammy Younge, Jr. for his defiance of segregation laws in Alabama.

The SNCC statement read in part:

“The murder of Samuel Younge in Tuskegee, Alabama, is no different than the murder of peasants in Vietnam. For both Younge and the Vietnamese sought and are seeking to secure the rights guaranteed them by law. In each case, the United States government bears a great part of the responsibility for these deaths. Samuel Younge was murdered because United States law is not being enforced. Vietnamese are murdered because the United States is pursuing an aggressive policy in violation of international law. The United States is no respecter of persons or law when such persons or laws run counter to its needs or desires.” (Source)

Julian Bond, a longtime SNCC organizer, had run successfully for the state legislature in late 1965. However, the authorities denied him the right to take his seat after he said publically that the SNCC position on Vietnam was his own as well.

Later in August 1966, the SNCC chapter in Atlanta embarked upon a campaign to expose the racist character of the Vietnam War both domestically and within Southeast Asia. Women and men organizers in and around SNCC set up picket lines outside the induction center located near the heart of the African American community.

These demonstrations soon prompted attacks by hostile mobs of whites along with police officers. Protesters were called racist slurs, had cigarettes dropped out of windows by military personnel onto the picket lines, there was water and other objects thrown as well combined with outright physical assaults. Demonstrators then attempted to occupy a space in the induction center to demand a halt to the racist attacks. (Source)

An ensuing struggle led to arrests and terms in prison. SNCC organizers Michael Simmons and Larry Fox wrote a report summing up their experiences. They discussed a tour after being released from jail which visited cities such as Detroit in an effort to build an alliance of draft resisters, lawyers and political activists working on other related issues. (Source)

1966 was the year that there was a radical change in the character of SNCC’s leadership with the takeover by Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture) as chairman who had direct organizing experience in Mississippi in 1964 and Alabama in 1965-66, where the Lowndes Country Freedom Organization (LCFO) was formed and became known as the Black Panther Party. There was an intensification of anti-war work and the linking of the African American liberation struggle with global developments in Vietnam, notwithstanding events in other regions of Asia along with Africa, the Middle East, the Caribbean and Latin America.

SNCC activists such Diane Nash, a veteran of the Nashville Civil Rights Movement and the freedom rides of 1960-61, traveled to North Vietnam in 1966 to call for the end of U.S. aggression through addresses over Radio Hanoi. Gwen Patton, graduate of Tuskegee University, was instrumental as well in organizing efforts to build the antiwar movement among African Americans.

According to a report by Ashley Farmer on Patton’s contributions, the writer notes that:

“After leaving Tuskegee, she helped organize the National Black Antiwar Antidraft Union (NBAWADU), designed to develop a black-centered anti-war and anti-imperialist front. As the Executive Secretary of the group, Patton penned some of the black freedom movement’s foundational anti-war documents, including speeches on the ‘Role of Women in Revolution.’ She also developed a bevy of position papers that connected American imperialist atrocities abroad with the state’s treatment of black Americans at home. Patton constantly centered black women within her pro-black, anti-imperialist politics, making her a foundational figure in late 1960s black feminist theorizing. Living and working alongside SNCC organizers like Faye Bellamy and Ethel Minor foregrounded the importance of developing emancipatory projects that were gender-inclusive. Patton was largely responsible for creating the Black Women’s Liberation Committee (BWLC), a women’s collective within SNCC. This group engaged in central questions about the ideological underpinnings of women, gender roles, and revolution. The philosophical foundations that Patton developed in BWLC documents became the ideological scaffolding for the Third World Women’s Alliance, or TWWA, one of the first groups to formally organize around an intersectional platform. Patton also authored many articles addressing the complex gender politics embedded in Black Power organizing. She was one of the activists who contributed to Toni Cade Bambara’s now classic The Black Woman: An Anthology. Her article about the ‘Victorian Ethos’ was an early take on the pitfalls of respectability politics in political organizing.”

SNCC viewed the struggle for Black Liberation as part and parcel of the revolutionary movements sweeping Asia, Africa and other areas of the world. An International Section was created and directed by James Forman, the former executive secretary. By 1967, Forman would be presenting papers in national and international forums expressing solidarity with the Vietnamese and independence movements in Southern Africa, among other geo-political areas.

By early 1967, Dr. King was rapidly becoming outspoken about his opposition to the Vietnam War through a series of newspaper columns, speeches in California, an anti-war march in Chicago in late March and the famous Riverside Church address, dubbed Beyond Vietnam on April 4, just one year-to-date before his assassination in Memphis. On April 15, King spoke alongside Carmichael outside the United Nations in New York to thousands of opponents of the war.

Muhammad Ali, the heavyweight champion of the world, was one of the most widely known personalities internationally. Ali had changed his name from Cassius Clay to an Islamic one when he went public with his conversion to the NOI after winning the championship in early 1964. During this period in early 1964, Ali was close to Malcolm X who later left the NOI by late March causing an irreparable breech between the two men, with the heavyweight champion remaining with Elijah Muhammad.

However, after Malcolm X’s assassination on February 21, 1965 in New York, SNCC and other organizations moved more in the ideological direction of the former national spokesman for Elijah Muhammad. By 1966, Ali was being hounded by the draft board. He officially refused induction in early 1967 citing religious grounds. Ali also emphasized that he did not feel obligated to wage war against the Vietnamese people based upon the lack of freedom for the Black man in the U.S.

Both Dr. King and SNCC supported Ali in his decision. This opened the way for broader alliances in opposition to the Vietnam War.

By May 1967, Stokely Carmichael had completed one year as chair of SNCC turning over the reign of leadership to H. Rap Brown (later known as Jamil Abdullah Al-Amin). Carmichael visited England for a conference on the Dialectics of Liberation. He would later go to Cuba and address a summit of Latin American liberation organizations, attracting the attention through his speech of Premier Fidel Castro. During his time outside the U.S., Carmichael also visited Guinea, Egypt, Algeria, Tanzania and other states.

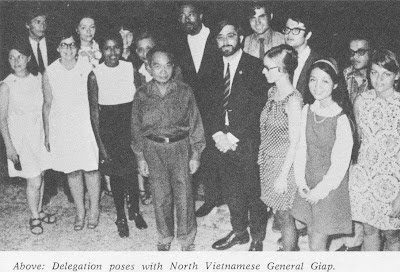

He also traveled to Hanoi and met with Ho Chi Minh. Carmichael subsequently reported that Ho encouraged him to focus more attention on the African Revolution. While in Hanoi, the former SNCC chairman requested a seminar on the building of a united front such as the NLF.

In recounting this event, Carmichael revealed that after the seminar started the U.S. began bombing Hanoi. The Vietnamese party leaders then moved Carmichael into a bunker in order to continue the course. One bomb struck near the location of the session causing some debris to fall on the notes of the instructor. Carmichael recounted how the dust was wiped away quickly and the class continued without interruption.

“When I saw this I knew that the Americans would be defeated“, he jovially said. (Lecture delivered at Wayne State University in Detroit, March 13, 1992)

Robert F. Williams had been the president of the NAACP chapter in Monroe, North Carolina when he advocated and practiced armed self-defense against the Ku Klux Klan. Williams’ refusal to categorically accept the nonviolent approach to civil rights later resulted in his expulsion from the NAACP in 1961. Eventually he was forced to leave North Carolina amid an attempt to frame him on false kidnapping charges of a white couple.

After being transported out of North Carolina by supporters, Williams eventually settled in Cuba and later the People’s Republic of China. He spent time as well in North Vietnam addressing radio broadcasts to African American GIs, exposing the racist and imperialist character of the war.

Perhaps the apex of solidarity between African Americans and the Vietnamese Revolution emerged when the Black Panther Party leader Bobby Seale attended a conference in Montreal, Quebec in late 1968 where the NLF representatives recognized the party as the vanguard of the revolutionary movement in the U.S. The BPP in return pledged their full recognition of the NLF as the legitimate government of South Vietnam.

The following year saw efforts at deeper cooperation when the North Vietnamese government offered to release American POWs in exchange for the freedom of BPP leaders Chairman Bobby Seale and Minister of Defense Huey P. Newton. This offer was immediately rejected by the administration of then President Richard M. Nixon.

However, in August 1970, after the release of Huey P. Newton on appeal bond related to charges of murdering and wounding two white Oakland police officers, the BPP Minister of Defense pledged to send some of his members to join the armed wing of the Vietnamese Revolution as an act of solidarity. In 1971, Newton and Elaine Brown, Central Committee members of the BPP, visited China where they met with Premiere Chou En Lai.

Burgeoning opposition to the Vietnam War among African American liberation organizations inspired resistance within the armed forces. Groups such as the GIs United Against the War and the Malcolm X Society posed a challenge to the largely white officers’ corps which utilized discrimination as a means of intimating African Americans and controlling discord within the ranks.

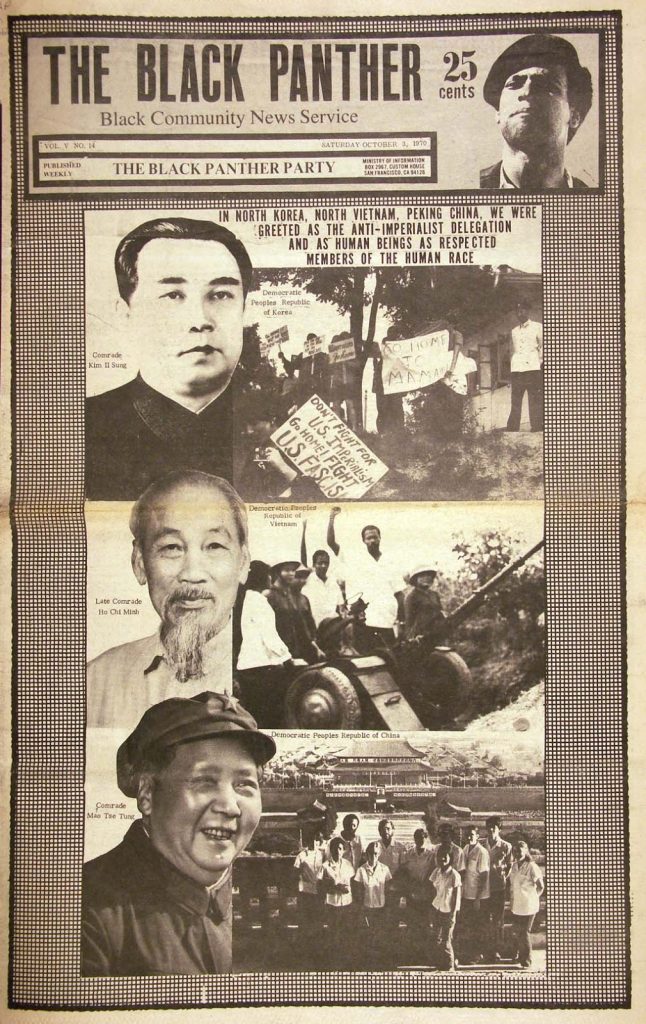

Black Panther newspaper in solidarity with DPRK, China and North Vietnam

Black soldiers grew Afro hairstyles and beards as acts of protest and defiance. Many were radicalized through their experience in Vietnam swelling the ranks of groups such as the BPP and the Black Liberation Army (BLA) upon their discharge.

Although the U.S. announced its withdrawal of ground forces from Vietnam in late 1972 after a horrendous round of bombings that December, the war continued until the fall of Saigon on April 30, 1975. After a decade of continuing defeats and Vietnamese advances, the U.S. Congress halted the funding of the war resulting in the collapse of the puppet regime in Saigon.

Contrastingly in the U.S., the political toll of state repression and cooptation from Washington and Wall Street severely derailed the revolutionary wing of the African American movement by the early 1970s. Robert F. Williams returned to the U.S. in late 1969. The BPP was wracked by an internal split in 1971 from which either faction was able to fully recover.

The onset of the restructuring of the world economy in 1975, coinciding with the defeat of imperialism in Southeast Asia, led to massive capital flight and disinvestment from American municipalities resulting in structural unemployment, deepening poverty among the working class reinforced by the rapid expansion of the prison-industrial-complex. A greater emphasis on electoral politics and business development could not fulfill the national aspirations of the African American people.

Some four decades or more since the end of the Vietnam War the African American people are still fighting against national oppression, class exploitation and government repression. The experience acquired during the successive administrations of the likes of Lyndon B. Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George Bush, Sr. through Bill Clinton, George Bush, Jr. to Barack Obama and now Donald Trump, necessitates a renewed effort to overcome the ruling class and its state apparatuses.

Lessons from the African American and Vietnamese Liberation Struggles

These events during the period of the 1950s through the mid-1970s are important to recount in light of the revisionist history surrounding the role of both white radicals and African Americans during the Vietnam War. Absent the persistent military and political fortitude of the Vietnamese people along with resistance from African Americans, both outside and inside the military, victory against imperialism would not have been possible without additional years of fighting.

The selective service system in the U.S. suffered a monumental setback when the draft was abolished in 1973. Later in 1980, registration was reinstituted while the draft has not been fully reinstated. However, there is an economic draft due to poverty and joblessness that has fueled the war machine through the wars launched by Washington in Iraq, Afghanistan, Haiti and the present targeted attacks, deployment and commando operations prevalent in Somalia, Niger, Yemen, Syria and Iraq.

In the first year of the administration of Trump, tensions have escalated with the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) whose nuclear program has served as a pointed warning to the Pentagon and other potential adversaries. People’s China has developed into the second largest economy in the world while its conventional military forces total more than three million well-trained and armed soldiers.

Expenditures by the taxpayers in the U.S. to the military and security apparatus totals at least $1trillion annually when the funding for both the Pentagon and intelligence services are taken into account. Washington’s defense budget is larger than all other states combined although it cannot create a sense of sustainable security for the ruling class.

Despite all of its rhetoric and sloganeering, the U.S. ruling class remains insecure. The advent of Trump is a manifestation of the paranoid atmosphere existing among the imperialists in the Western capitalist nations.

African Americans have no other choice than to reject the Pentagon war machine since it has only resulted in their underdevelopment, displacement and ongoing national oppression. The eventual demise of U.S. imperialism can only strengthen the struggle for liberation and social emancipation of the oppressed.

*

All images in this article are from the author.