African American Resistance in the Rural South from the Sharecroppers Union to the New Farmers of America

During the Great Depression in Alabama, a communist-led agricultural based organization was built in defiance of racial terror and the massive dislocation of millions

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (desktop version)

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Several years prior to the formation of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU) in 1934, a series of events in the state of Alabama would give rise to the formation of the Sharecroppers Union (SCU).

This organization was founded with the assistance of African American leaders within the Communist Party in Alabama largely centered in the steel industry in Birmingham.

After the collapse on Wall Street in October 1929 and the inability of the United States government to enact effective programs to assist people living in rural areas, African American sharecroppers, tenant farmers and agricultural laborers were eager to seek assistance and redress for their burgeoning social problems. The SCU, also known as the Alabama Sharecroppers Union (ASU), arose during a period of efforts by the Communist Party (CP) to organize among the African American people in both the rural and urban areas.

As early as 1925, the CP had established the American Negro Labor Congress (ANLC) utilizing a small cadre of African Americans from the U.S. and the Caribbean who had joined the organization during the post-World War I years. This attempt gained modest results during the mid-to-late 1920s.

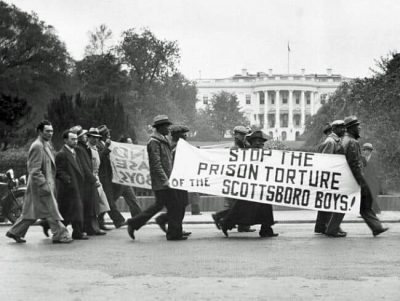

Nonetheless, the Great Depression intensified the levels of exploitation and oppression directed against the African American people in the rural South. On March 25, 1931, nine African American youth jumped onto a freight train in Chattanooga, Tennessee headed for Alabama. They were later falsely accused of raping two white women and faced the death penalty in the state of Alabama.

These youth became known internationally as the Scottsboro Nine. They were Haywood Patterson, Olen Montgomery, Clarence Norris, Willie Roberson, Andy Wright, Ozzie Powell, Eugene Williams, Charley Weems, and Roy Wright. In a sham trial, eight of the nine were convicted and sentenced to death by an all-white jury. In response to national and worldwide protests, their case went to the Supreme Court where their convictions were overturned in Powell v. State of Alabama (1932).

The State of Alabama would retry the defendants resulting in additional convictions. Appeals and other legal actions continued through the late 1940s until the final defendant released and granted parole fled to the state of Michigan.

A year before the Scottsboro Nine travesty of justice, the CP organized the League of Struggle for Negro Rights (LSNR) in 1930 as its continuation of the ANLC project. The LSNR played an important role in building support for the International Labor Defense campaign to free the nine African American youth.

It was within this context that the SCU was established in the summer of 1931. Once the landowners, law-enforcement officers and white racist vigilantes discovered the SCU activities, the organization was met with severe repression resulting in the deaths of several African American farmers and agricultural workers and the framing of others on bogus criminal charges.

Sharecroppers Union and the Right to Self-Determination

After the 1928 Sixth Congress of the Communist International in Moscow, major shifts were carried out in the overall general line and strategy of its affiliates in the U.S. Seeking to combat white chauvinism and taking the lead from African American communists such as Harry Haywood, the party accepted the notion that the Black masses in the South were an oppressed people with the right to self-determination. This position can also be traced back to the Second Congress of the Communist International in 1920 where Lenin acknowledged the plight of the African American people in the U.S. See this.

According to the Encyclopedia of Alabama:

“By 1932, the ASU had attracted nearly 600 members. One such member was Ned Cobb of Tallapoosa County. A successful cotton farmer, he gained greater renown late in his life when his recollections of sharecropping and union activism on behalf of Black farmers were retold in All God’s Dangers: The Life of Nate Shaw, which was published in 1974. Two native Tallapoosa sharecroppers, brothers Ralph and Tommy Gray, were the first to attract a sizable following. They initially arranged for Coad and other organizers to hold a meeting at a local church in Tallapoosa County, but they met heavy resistance from local authorities. On July 15, in a clash between the local sheriff and a number of ASU members, Ralph Gray was killed. The following day, ASU members were arrested and four were lynched for their involvement in the meeting.”

The SCU (or ASU) continued to gain ground in Alabama and some other states in the South. By 1935, the organization claimed 10,000 members which were overwhelmingly African American.

Nonetheless, the degree of violent repression and racism throughout Alabama and other areas where the SCU had opened branches, had forced the organizing efforts underground since 1931 when several organizers were lynched. Despite its successful membership drives and underground activities, the CP after 1934-35 moved towards its “Popular Front” strategy seeking to coalesce its organizational efforts with non-communist groupings such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the all-Black Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and Maids headed by African American socialist, journalist and trade unionist, A. Phillip Randolph, among others.

In 1935, a decision was made to convene a National Negro Congress (NNC) which met in February 1936 in Chicago with 800 delegates. A. Phillip Randolph was elected as president along with journalist John P. Davis as vice-president.

These developments resulted in the withdrawal of support for the SCU after 1936 by the Communist Party leadership. The fact that the SCU had operated on a clandestine basis with semi-autonomous branches throughout Alabama and other areas, they were able to continue as independent units well into the 1940s.

New Deal Agricultural Policy and the New Farmers of America

Independent organizing on the part of African Americans outside the influence of the Republican and Democratic Parties was by no means contingent upon the efforts of the CP and its mass groupings. The existence of numerous organizations such as the National Colored Farmers Alliance of the late 19th century and the Progressive Farmers and Household Union in Arkansas after World War I, was reflective of the self-organizing traditions which emerged during the period of enslavement and Reconstruction in the U.S.

The Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU) formed in 1934 composed of a majority African American base existing among farmers and agricultural workers, did enjoy the administrative support of some leading figures within the Socialist Party. However, if there had not been the mass enthusiasm on the part of the African American people in the South, particularly within the churches, the efforts of the STFU would not have gained significant political traction.

Image: New Farmers of America was an all-African American youth organization during the 1930s to the 1960s

The New Farmers of America (NFA) is one such example among African Americans which emerged during the late 1920s and early 1930s. By the time of the second administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, farm policy had shifted after the Supreme Court decision which declared the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) as unconstitutional in 1936. (See this)

By 1937, resettlement and assistance programs for impoverished, exploited and dislocated farmers and agricultural workers were established. The Bankhead-Jones Farm Tenant Act was passed and provided the legal authority of the federal government to acquire damaged and unproductive land for rehabilitation and redistribution to destitute sharecroppers.

Although the NFA was more associated with the Department of Education and operated through the segregated school systems in the South, a source on the organization reported that:

“The NFA started as a localized movement in Virginia around 1927. H.O. Sargent, Federal Agent for Agricultural Education for Negroes, and G.W. Owens, Teacher-Trainer at Virginia State College, were two of the earliest proponents of an organization for African American farm youth. While Owens wrote the constitution for the New Farmers of Virginia and helped lay the foundation for what would become a national organization, Sargent lobbied within the Department of Education to officially create an organization in segregated schools. As the idea grew in popularity, chapters formed sporadically throughout the southern states and region. In reaction to the emergence of chapters, the states organized into state and sectional associations based on proximity. These sections held conferences and contests unifying the state associations until a national organization was officially created on August 4, 1935.”

The NFA provided educational resources to improve production and efficiency among African American farmers. The organization continued from 1935 to 1965, when in response to the Civil Rights Movement and the passage of the Civil and Voting Rights Acts of 1965, merged with the white-dominated Future Farmers of America (FFA).

Black Land Loss and the Great Migration

During World War II and its aftermath, there were additional incentives for African Americans and whites to leave the rural South. Racial terror continued after 1945 when over one million African American men and women soldiers returned to their communities with a renewed determination to end Jim Crow and its economic underpinnings.

Several high-profile lynchings and the advent of the Cold War during 1946-1949, stiffened the ruling class resistance to the demands for civil rights and universal suffrage. Land accumulated by African Americans after the Civil War and Reconstruction rapidly declined as the system of segregation and economic exploitation forced millions more off their farms.

Nonetheless, the struggle would continue with the emergence of the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955-56, the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in 1960 and the growing militancy of African Americans in the South. In future articles we will examine the nexus between organizing in the rural areas and the advent of the mass Civil Rights Movement during the 1950s and 1960s.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Abayomi Azikiwe is the editor of the Pan-African News Wire. He is a regular contributor to Global Research.

Featured image: Scottsboro case demonstration in Washington, D.C. during 1933 (Source: Abayomi Azikiwe)