Afghanistan, the Forgotten Proxy War

Part I

First published on April 30, 2019

July 3, 2019 marks the 40th anniversary of when the United States’ first military assault against Afghanistan with the CIA-backed Mujahideen began. It would be a mistake to treat the present-day conflict as being separate from the U.S. intervention that began in 1979 against the then-government of the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan. Afghanistan was not always known as the chaotic, ‘failed state’ overrun by warlords as it is now; this phenomenon is a product of that U.S.-led regime change operation. The article below, originally published on March 30, 2019, summarizes and analyzes the events that transpired during and after the Cold War years as they relate to this often misunderstood, if not overlooked, aspect of the long war against Afghanistan.

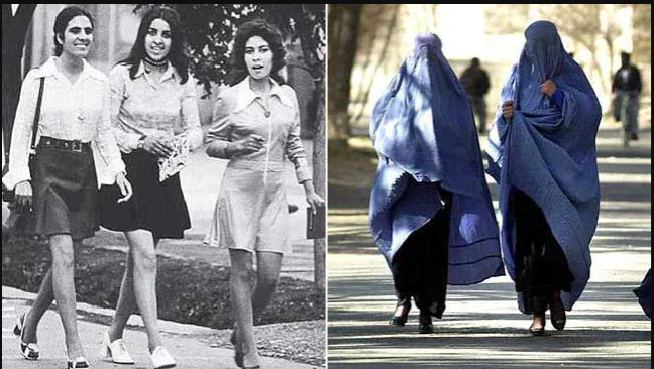

When it comes to war-torn Afghanistan and the role played by the United States and its NATO allies, what comes first to mind for most is the ‘War on Terror’ campaign launched in 2001 by George W. Bush almost immediately after the 9/11 attacks. And understandably so, considering that the United States and its allies established a direct “boots-on-the-ground” military presence in the country that year. Not only that, but during the Bush-Cheney years, there was an aggressive propaganda campaign being played out across U.S. media outlets which used women’s rights as one of the pretexts for the continued occupation. The irony of this, however, is not lost on those who understand that the conflict in Afghanistan has a long history which, much like Syria, stretches as far back as the Cold War era — especially when it was the United States that provided support for the Mujahideen in destabilizing the country and stripping away the modernizing, progressive economic and social gains, including Afghan women’s emancipation, which the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) had fought for. With the overthrow of the independent Soviet-aligned PDPA government, the Taliban emerged as a powerful faction of the Mujahideen; the U.S. would develop a working relationship with the Taliban in 1995. The war was never truly about women’s rights or other humanitarian concerns, as Stephen Gowans explains:

“Further evidence of Washington’s supreme indifference to the rights of women abroad is evidenced by the role it played in undermining a progressive government in Afghanistan that sought to release women from the grip of traditional Islamic anti-women practices. In the 1980s, Kabul was “a cosmopolitan city. Artists and hippies flocked to the capital. Women studied agriculture, engineering and business at the city’s university. Afghan women held government jobs.” There were female members of parliament, and women drove cars, and travelled and went on dates, without needing to ask a male guardian for permission. That this is no longer true is largely due to a secret decision made in the summer of 1979 by then US president Jimmy Carter and his national security adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski to draw “the Russians into the Afghan trap” and give “to the USSR its Vietnam War” by bankrolling and organizing Islamic fundamentalist terrorists to fight a new government in Kabul led by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan.

The goal of the PDPA was to liberate Afghanistan from its backwardness. In the 1970s, only 12 percent of adults were literate. Life expectancy was 42 years and infant mortality the highest in the world. Half the population suffered from TB and one-quarter from malaria.”

Moreover, and contrary to the commonly held belief that the conflict in Afghanistan started in 2001, it would be more accurate to say that the war started in 1979. As a matter of fact, the Carter Administration’s 1979 decision to overthrow the PDPA and destabilize Afghanistan is at the root of why the country is in the state that it continues to be in today.

Afghan women during the PDPA era vs. Afghan women today.

The Cold War – a new phase in the age of imperialism

The Democratic Republic of Afghanistan’s military welcome their Soviet counterparts

In the early 1900s, Vladimir Lenin observed that capitalism had entered into its globalist phase and that the age of imperialism had begun; this means that capitalism must expand beyond national borders, and that there is an internal logic to Empire-building and imperialist wars of aggression. Lenin defines imperialism as such:

“the concentration of production and capital has developed to such a high stage that it has created monopolies which play a decisive role in economic life; (2) the merging of bank capital with industrial capital, and the creation, on the basis of this “finance capital”, of a financial oligarchy; (3) the export of capital as distinguished from the export of commodities acquires exceptional importance; (4) the formation of international monopolist capitalist associations which share the world among themselves, and (5) the territorial division of the whole world among the biggest capitalist powers is completed. Imperialism is capitalism at that stage of development at which the dominance of monopolies and finance capital is established; in which the export of capital has acquired pronounced importance; in which the division of the world among the international trusts has begun, in which the division of all territories of the globe among the biggest capitalist powers has been completed.”

It should be clear that imperialism is not just merely the imposition of a country’s will on the rest of the world (although that is certainly a part of it). More precisely: it is a result of capital accumulation and is a process of empire-building and maintenance, which comes with holding back development worldwide and keeping the global masses impoverished; it is the international exercise of domination guided by economic interests. Thus, imperialism is less of a cultural phenomenon, and more so an economic one.

Lenin also theorized that imperialism and the cycle of World Wars were the products of competing national capitals between the advanced nations. As he wrote in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, World War I was about the competition between major imperialist powers — such as the competing capitals of Great Britain and Germany — over the control of and the split of plunder from colonies. Thus, finance capital was the driving force behind the exploitation and colonization of the oppressed nations; these antagonisms would eventually lead to a series of world wars as Lenin had predicted. During the First World War, the goals of the two imperial blocs of power were the acquisition, preservation, and expansion of territories considered to be strategic points and of great importance to their national economies. And during the Great Depression, protectionist measures were taken up by Britain, the United States, and France to restrict the emerging industrial nations — Germany, Italy, and Japan, also known as the Axis states — from access to more colonies and territories, thereby restricting them from access to raw materials and markets in the lead up to World War II. In particular, the two advanced capitalist industrialized powers of Germany and Japan, in their efforts to conquer new territory, threatened the economic space of Britain, the U.S., and France and threatened to take their territories, colonies, and semi-colonies by force — with Germany launching a series of aggressions in most of Europe, and Japan in Asia. WWII was, in many ways, a re-ignition of the inter-imperialist rivalry between the Anglo-French bloc and the German bloc, but with modern artillery and the significant use of aerial assaults. It was also a period of the second stage of the crisis of capitalism which saw the rise of Fascism as a reaction to Communism, with the Axis states threatening to establish a world-dominating fascist regime. For the time being, WWII would be the last we would see of world wars.

At the end of WWII, two rival global powers emerged: the United States and the Soviet Union; the Cold War was a manifestation of their ideological conflict. The Cold War era was a new phase for international capital as it saw the advent of nuclear weapons and the beginning stages of proxy warfare. It was a time when the imperialist nations, regardless of which side they were on during WWII, found a common interest in stopping the spread of Communism and seeking the destruction of the Soviet Union. By extension, these anti-communist attacks would be aimed at the Soviet-allied nations as well. This would increase the number of client states with puppet governments acting in accordance with U.S. interests who would join the NATO bloc with the ultimate aim of isolating the Soviet Union. It should also be noted that the end of WWII marked the end of competing national capitals such that now, financial capital exists globally and can move instantaneously, with Washington being the world dominating force that holds a monopoly over the global markets. Those countries who have actively resisted against the U.S. Empire and have not accepted U.S. capital into their countries are threatened with sanctions and military intervention — such as the independent sovereign nations of Syria and North Korea who are, to this day, still challenging U.S. hegemony. Afghanistan under the PDPA was one such country which stood up to U.S. imperialism and thus became a target for regime change.

In addition to implementing land reforms, women’s rights, and egalitarian and collectivist economic policies, the PDPA sought to put an end to opium poppy cultivation. The British Empire planted the first opium poppy fields in Afghanistan during the 1800s when the country was still under the feudal landholding system; up until the king was deposed in 1973, the opium trade was a lucrative business and the Afghan poppy fields produced more than 70 percent of opium needed for the world’s heroin supply. These reforms in 1978 would eventually attract opposition from the United States, which had already embarked on its anti-communist crusade, providing backing to reactionary forces dedicated to fighting against various post-colonial progressive governments, many of which were a part of the ‘Soviet Bloc’ — such as the right-wing Contras in Nicaragua who mounted violent opposition to the Sandinista government. Despite having gained independence on its own merits, Afghanistan under the PDPA — much like other Soviet-allied, postcolonial successes such as Cuba, Nicaragua, Syria, Libya, and North Korea — was seen as a “Soviet satellite” that needed to be brought back under colonial domination, and whose commodities needed to be put under the exclusive control and possession of the United States. Not only that, but it was considered a strategic point of interest that could be used to enclose upon the Soviet Union.

In order to undermine the then-newly formed and popular PDPA government, the Carter administration and the CIA began the imperialist intervention by providing training, financial support, and weapons to Sunni extremists (the Mujahideen) who started committing acts of terrorism against schools and teachers in rural areas. With the assistance of the Saudi and Pakistani militaries, the CIA gathered together ousted feudal landlords, reactionary tribal chiefs, sectarian Sunni clerics, and cartel drug lords to form a coalition to destabilize Afghanistan. On September 1979, Noor Mohammed Taraki — the first PDPA leader and President of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan — was assassinated during the events of the CIA-backed coup, which was quickly stopped by the Afghan army. However, by late 1979, the PDPA was becoming overwhelmed by the large-scale military intervention by U.S. proxy forces — a combination of foreign mercenaries and Afghan Ancien Régime-sympathizers — and so they decided to make a request to the USSR to deploy a contingent of troops for assistance. The Soviet intervention provided some much-needed relief for the PDPA forces — if only for the next ten years, for the U.S. and Saudi Arabia “upped the ante” by pouring about $40 billion into the war and recruiting and arming around 100,000 more foreign mercenaries. In 1989, Mikhail Gorbachev would call on the Soviet troops to be withdrawn, and the PDPA was eventually defeated with the fall of Kabul in April 1992. Chaos ensued as the Mujahideen fell into infighting with the formation of rival factions competing for territorial space and also wreaking havoc across cities, looting, terrorizing civilians, hosting mass executions in football stadiums, ethnically-cleansing non-Pashtun minorities, and committing mass rapes against Afghan women and girls. Soon afterwards in 1995, one of the warring factions, the Taliban, consolidated power with backing from the United States, Saudi Arabia, and Pakistan. On September 28, 1996 the last PDPA Presidential leader, Mohammad Najibullah, was abducted from his local UN compound (where he had been granted sanctuary), tortured, and brutally murdered by Taliban soldiers; they strung his mutilated body from a light pole for public display.

A renewed opium trade, and the economic roots of Empire-building

U.S. troops guarding an opium poppy field in Afghanistan.

“Once the heroin left these labs in Pakistan’s northwest frontier, the Sicilian Mafia imported the drugs into the U.S., where they soon captured sixty percent of the U.S. heroin market. That is to say, sixty percent of the U.S. heroin supply came indirectly from a CIA operation. During the decade of this operation, the 1980s, the substantial DEA contingent in Islamabad made no arrests and participated in no seizures, allowing the syndicates a de facto free hand to export heroin.”

It is apparent that by putting an end to the cultivation of opium poppy, in addition to using the country’s resources to modernize and uplift its own population, the independent nationalist government of the PDPA was seen as a threat to U.S. interests that needed to be eliminated. A major objective of the U.S.-led Mujahideen — or any kind of U.S. military-led action for that matter — against Afghanistan had always been to restore and secure the opium trade. After all, it was during the 1970s that drug trafficking served as the CIA’s primary source of funding for paramilitary forces against anti-imperialist governments and liberation movements in the Global South, in addition to protecting U.S. assets abroad. Also, the CIA’s international drug trafficking ties go as far back as 1949, which is the year when Washington’s long war on the Korean Peninsula began. The move by the PDPA to eradicate opium-poppy harvesting and put an end to the exploitation brought about by the drug cartels was seen as “going too far” by U.S. imperialists. A significantly large loss in opium production would mean a huge loss in profits for Wall Street and major international banks, which have a vested interest in the drug trade. In fact, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) reported that money-laundering made up 2-5% of the world economy’s GDP and that a large percentage of the annual money-laundering, which was worth 590 billion to 1.5 trillion dollars, had direct links to the drug trade. The profits generated from the drug trade are often placed in American-British-controlled offshore banks.

The rationale behind the PDPA’s campaign to eradicate the opium poppy harvest was based not only on practical health reasons, but also on the role played by narcotics in the history of colonialism in Asia. Historically, cartel drug lords enabled imperialist nations, served bourgeois interests, and used cheap exploited slave labour. Oftentimes, the peasants who toiled in these poppy fields would find themselves becoming addicted to heroin in addition to being, quite literally, worked to death. Cartels are understood to be monopolistic alliances in which partners agree on the conditions of sale and terms of payment and divide the markets amongst themselves by fixing the prices and the quantity of goods to be produced. Now, concerning the role of cartels in ‘late-stage capitalism’, Lenin wrote:

“Monopolist capitalist associations, cartels, syndicates and trusts first divided the home market among themselves and obtained more or less complete possession of the industry of their own country. But under capitalism the home market is inevitably bound up with the foreign market. Capitalism long ago created a world market. As the export of capital increased, and as the foreign and colonial connections and “spheres of influence” of the big monopolist associations expanded in all ways, things “naturally” gravitated towards an international agreement among these associations, and towards the formation of international cartels.

This is a new stage of world concentration of capital and production, incomparably higher than the preceding stages.”

International cartels, especially drug cartels, are symptoms of how capital has expanded globally and has adapted to create a global wealth divide based on the territorial division of the world, the scramble for colonies, and “the struggle for spheres of influence.” More specifically, international cartels serve as stewards for the imperialist nations in the plundering of the oppressed or colonized nations. Hence the mass campaigns to help end addictions and to crack down on drug traffickers which were not only implemented in Afghanistan under the PDPA, but in Revolutionary China in 1949 and by other anti-imperialist movements as well. Of course, the opium traffickers and their organized crime associates in Afghanistan saw the campaign against opium poppy cultivation, among other progressive reforms, as an affront; this made them ideal recruits for the Mujahideen.

But why the “breakdown” in the relationship between the U.S. and the Taliban from the early 2000s and onwards? Keep in mind that, again, the members of the Taliban were amongst the various factions that made up the Mujahideen whose partnership with the United States extends as far back as the late 1970s; and it was clear that the U.S. was aware that it was working with Islamic fundamentalists. The human rights abuses committed by the Taliban while in power were well-documented before their relations with the U.S. soured by the year 2000. What made these relations turn sour was the fact that the Taliban had decided to drastically reduce the opium poppy cultivation. This led to the direct U.S. military intervention of 2001 in Afghanistan and the subsequent overthrow of the Taliban; the U.S. used the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon as a pretext even if there was no proof that the Taliban had a hand in them or had been in contact with Osama bin Laden at all during that time. The U.S. would soon replace the Taliban with another faction of the Mujahideen that was more compliant with the rules that the imperialists had set out. In other words, the Taliban were ousted not necessarily because they posed a significant challenge to U.S. hegemony as the PDPA had, or because of their treatment of women — nor were they hiding Osama bin Laden; it was because they had become more of liabilities than assets. It is yet another case of the Empire discarding its puppets when they have outlived their usefulness due to incompetence and being unable to “follow the rules properly” — not unlike the U.S. removal of military dictator Manuel Noriega who was staunchly pro-American and who, in collaboration with fellow CIA asset and notorious cartel drug kingpin Pablo Escobar, previously sold drugs for the CIA to help finance the anti-communist campaign in Central America.

George W. Bush visits Hamid Karzai, who participated in the Mujahideen in the past and led the puppet government that replaced the Taliban.

Although the United States has always been one of the top producers of oil in the world, another reason for establishing a permanent U.S. military presence in Afghanistan was to gain control over its vast untapped oil reserves, which the U.S. had known about prior to 9/11. Oil is yet another lucrative commodity, and ensuring that Afghanistan had a compliant government that would acquiesce to its demands was important for the U.S. in this aspect as well. Naturally, the nationalist government of the PDPA was also seen as a threat to the profit-making interests of U.S. oil companies, and any nation that was an independent oil producer (or merely a potential independent oil producer, in Afghanistan’s case) was seen as an annoying competitor by the United States. However, Afghanistan would not begin its first commercial oil production until 2013, partly because of the ongoing geopolitical instability, but also because opium production continues to dominate the economy. Plus, it is likely that neither the monarchy nor the PDPA realized that there existed such vast untapped oil reserves since there were very limited volumes of oil (compared to the higher volumes of natural gas) being produced from 1957 to 1989, and which stopped as soon as the Soviet troops left. Later, reassessments were made during the 1990s; hence the U.S. ‘discovery’ of the untapped petroleum potential. But, when intensive negotiations between U.S.-based oil company Unocal and the Taliban went unresolved in 1998 due to a dispute over a pipeline deal that the latter wanted to strike with a competing Argentine company, it would lead to growing tensions between the U.S. and the Taliban. The reason for the dispute was that Unocal wanted to have primary control over the pipeline located between Afghanistan and Pakistan that crossed into the Indian Ocean. From this point on, the U.S. was starting to see the Taliban as a liability in its prerogative of establishing political and economic dominance over Central and West Asia.

In either case, oil and other “strategic” raw materials such as opium are essential for the U.S. to maintain its global monopolistic power. It is here that we see a manifestation of the economic roots of empire-building.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Continued in Part 2.

Originally published by LLCO.org on March 30, 2019. For the full-length article and bibliography, click here.

Janelle Velina is a Toronto-based political analyst, writer, and an editor and frequent contributor for New-Power.org and LLCO.org. She also has a blog at geopoliticaloutlook.blogspot.com.

All images in this article are from the author; featured image: Brzezinski visits Osama bin Laden and other Mujahideen fighters during training.