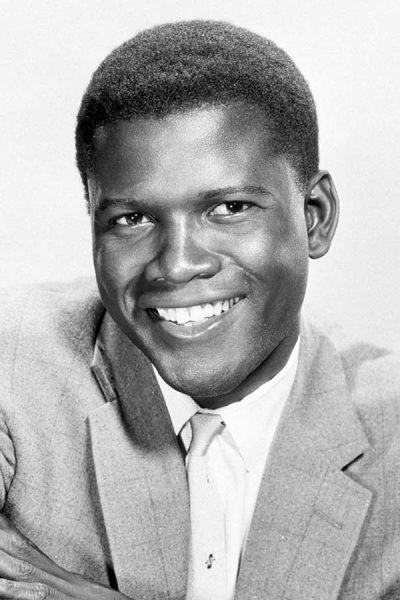

A Tribute to Sidney Poitier

Actor helped break color barrier in Hollywood while starring in films that advanced social justice causes and provoked critical thinking

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @globalresearch_crg.

***

The January 6 death of Sidney Poitier came at a portentous time. The screen’s seminal Civil Rights icon died on the one-year anniversary of an attempted insurrection by Confederate flag-waving white supremacists and as the voting rights he had campaigned for remained in limbo.

More than the career of any other major actor in Hollywood history, the motion picture odyssey of the man who became the first Black male to win an Oscar for playing Homer Smith resembles a tightrope act. Poitier, who was born in 1927 in Miami but raised in the Bahamas, somehow had to fulfill the expectations of two constituencies: Obviously, of Blacks, but also of whites, who formed the dominant majority culture, bought most movie tickets and financed films. To please both audiences Poitier had to somehow perform a delicate, intricate balancing act between appearing to be an Uncle Tom on the one hand and an “uppity” you-know-what on the other.

The following is a motion picture postmortem, an analysis of the political highlights and meanings of Sidney Poitier’s screen career, which stretched for more than half a century and included at least 55 acting credits and more.

In terms of the African-American screen image, Poitier was a transitional figure. In D.W. Griffith’s 1915 racist epic The Birth of a Nation, the Ku Klux Klan put the Reconstruction Era’s Badass Brothers and Sisters back into “their place.” For the next 35 years or so Black actors played mostly subservient, sexless, superstitious, celluloid stereotypes typified by Stepin Fetchit, Mantan Moreland and Butterfly McQueen.

Then three things happened that would change these humiliating onscreen depictions: The independence movements in Africa; the Civil Rights cause in the segregated South; and World War II. Blacks who fought against fascism abroad were unwilling to continue accepting racism at home. One of those WWII-era veterans was Poitier, who lied about his age while he was only 16 to join the Army.

In Sidney’s first credited movie role, 1950’s No Way Out, he plays a doctor who treats the criminal Richard Widmark, despite his abusive racism. The film, directed and co-written by Joe Mankiewicz, also depicts a race riot. In a way, No Way Out set the template for Sidney’s most successful screen image, as the noble Black who loftily sacrifices himself for ignoble whites.

Sidney Poitier in No Way Out (1950). [Source: irishnews.com]

But before he returned to this motion picture persona Poitier played a reverend in the 1951 South Africa-set anti-apartheid drama Cry, the Beloved Country, clandestinely co-written by the blacklisted Communist Party member John Howard Lawson, one of the Hollywood Ten.

Source: imdb.com

In 1957 Poitier co-starred in three roles that were departures from the “Good Negro” characters. In the Civil War drama Band of Angels, featuring Gone with the Wind’s Clark Gable, Poitier plays a plantation “House Negro” who escapes and joins the Union Army. In Something of Value opposite Rock Hudson, Sidney became a leader of the violent Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya against British colonialism. In The Mark of the Hawk, Poitier plays a character with the presidential sounding name of “Obam” (!) and is again embroiled in Africa’s anti-colonial cause, but this time he opts for non-violence.

Poitier achieved greater success in Stanley Kramer’s 1958 The Defiant Ones, as an escaped convict who sacrifices himself for the bigoted prisoner he has been chained to. White audiences cheered when Sidney gave up his chance for freedom to instead help Tony Curtis, but according to James Baldwin, Black ticket buyers jeered this act of self-sacrifice.

Source: amazon.com

A Hollywood favorite, both of these were Oscar-nominated and The Defiant Ones received five more nominations, including for Best Picture, and won two Academy Awards (including for blacklisted screenwriter Ned Young, who used a pseudonym but was glimpsed in the opening credits).

Sidney played the crippled title character in Otto Preminger’s 1959 adaptation of the George Gershwin opera Porgy and Bess. He attained well-deserved acclaim for playing the chauffeur who yearns for a better life in 1961’s screen adaptation of Lorraine Hansberry’s “moving-on-up” Broadway hit A Raisin in the Sun.

That year, Poitier also co-starred with Paul Newman as expatriate jazz musicians who romance Diahann Carroll and Joanne Woodward in Paris Blues, directed and written by Martin Ritt and Walter Bernstein, who had both been blacklisted. Carroll pointedly reminds her expat beau that after their Parisian idyll, they eventually must return home to fight for their people’s rights.

In 1962’s Pressure Point, Poitier once again played a Black medical practitioner caring for a white racist, this time as a psychiatrist treating Bobby Darin’s imprisoned neo-Nazi.

In 1964—as LBJ was launching the Great Society—Poitier became the first Black performer to win a Best Actor Academy Award for a leading role and the first Black to win any Oscar since Hattie McDaniel had won for playing the slave-cum-servant Mammy in 1939’s Gone with the Wind.

As Homer Smith in 1963’s Lilies of the Field, Poitier is the lord’s servant, henpecked by nuns into building a chapel. Because they are celibate women of the cloth, handsome Sidney is allowed close proximity to these white females.

Source: wikipedia.org

But four years later, at the pinnacle of his stardom, Poitier was permitted to openly woo a white woman in Kramer’s Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? The year this tepid interracial romance was lensed, Sidney also starred in two other major releases, including as a teacher presiding over troubled white pupils from the slums of London’s East End in James Clavell’s pseudo-hip To Sir, with Love.

In 1967, Poitier had become the world’s number one box office star. Until that point, Poitier’s career trajectory had reflected the pro-integration, non-violent, Civil Rights Movement. But by 1967, as militants such as Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown and the Black Panthers vied with Dr. Martin Luther King for hegemony over the African-American masses, as civil disobedience competed with armed struggle. “Black Power” impacted movies, too.

In the third and best of the trilogy of Sidney’s 1967 productions, he played a Philadelphia detective who confronted Southern bigotry. Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won five, including for Best Picture, Best Writing and Best Actor for Rod Steiger.

There’s a key, compelling scene that has been repeatedly screened in TV tributes to Sidney after his death, wherein Poitier the tightrope walker transcended passive resistance, moved toward militancy and helped set the stage for the return of the Badass Brothers (who’d been banished from the screen by Griffith and his Klansmen in 1915) in militant and Blaxploitation pictures.

In this pivotal, singular sequence a prominent plantation owner slaps Poitier who, instead of just simply, subserviently taking it, slaps whitey back. When the powerful Endicott (Larry Gates) asks the police chief what he’s going to do about the blow, Steiger is staggered, at a loss as to how to react. It was the slap heard ’round the world, which may have cost Poitier another Oscar nomination but announced the emergence of a new movie militancy.

Poitier’s leftward-veering screen image reflected the offscreen Stokely vs. King, “The-Fire-Next-Time” vs. the “We-Shall-Overcome” dynamic and dialectic. As the title to Heat’ssequel suggests, Poitier insists upon his honorific—and, like Aretha, respect—in 1970’s They Call Me Mister Tibbs! Male Blacks are second-class “boys” no more. As the picket signs of protesters way down yonder in the land of cotton had been poignantly proclaiming: “I am a Man.”

The 1968 assassination of Reverend King and ensuing urban rebellions also marked the death knell of passive resistance as a viable tactic in the equal rights crusade. That same year, when the revolutionary H. Rap Brown (who famously said: “Violence… is as American as cherry pie”) became its Chairman, SNCC (which had already expelled all white members and staffers by 1967) changed its name from the Student NONVIOLENT Coordinating Committee to the Student NATIONAL Coordinating Committee.

Trying to stay timely and relevant, Poitier appeared in several movies with Black Power themes, although his characters were not necessarily militants per se. Carol Reed’s 1947 Odd Man Out IRA drama was adapted and updated, relocated to a Black militant milieu in Philadelphia in 1969’s The Lost Man. Poitier uses the activist group as a diversion in order to pull a heist.

When Poitier returns home in a small Southern town to attend his sister’s funeral in 1971’s Brother John, he is suspected of being an outside agitator from the North on a mission to incite Black folks. Instead, in a version of the “magical Negro” trope, this mystical movie reveals that John Kane is the messiah—and he’s Black! (Call it “Guess Who’s Second Coming to Dinner?”) In 1971 Sidney also reprised his role as Lt. Virgil Tibbs in The Organization, cooperating with a band of Black radicals to stop drug trafficking in the community.

While Poitier fights with a white lawman in Brother John, Melvin Van Peebles actually shoots and kills a Caucasian policeman for using excessive force as the title character in Sweet Sweetback’s Badasssss Song in the actor/writer/director’s trendsetting militant movie made the same year as the tamer Brother John. Like Van Peebles’ 1970 Watermelon Man, both of these indies were far more militant than any of Poitier’s political pictures and openly advocated armed self-defense.

In 1975’s South Africa-set, Kenya-shot The Wilby Conspiracy, Poitier is an anti-apartheid activist teamed up with Michael Caine, a pairing reminiscent of The Defiant Ones. Sidney went on to portray Thurgood Marshall in the 1991 TV miniseries Separate But Equal and as Nelson Mandela opposite Michael Caine again in another South Africa-set production, the so-so 1997 made-for-TV movie Mandela and de Klerk.

Source: imdb.com

But Poitier never fully made the transition for the new Black Consciousness audience and its expectations. His smooth, middle class, integrationist image and oeuvre were too ingrained for more politically aware, nationalistic, militant moviegoers of the sizzling sixties and seventies, as the Black proletariat replaced the Black bourgeoisie.

Although Poitier continued to act, he started directing mass entertainment pictures that he sometimes also acted in and were particularly popular with African-American audiences, starting with the 1972 Western Buck and the Preacher, co-starring Harry Belafonte. Most of the nine movies Sidney helmed featured Black casts and were more lighthearted fare, comedies and/or shoot-’em-ups, starring actors such as Bill Cosby, Richard Pryor, and also Gene Wilder.

Poitier’s movie moment as the top box office attraction for the Civil Rights period had passed as he became increasingly passe. The Blaxploitation genre largely stripped Sweetback of its political awareness while perpetuating some of Van Peebles’ empowering elements with muscular, sexualized, nitty-gritty characters such as Shaft, Superfly or “Dracula’s soul brother,” Blacula. With an eye on the dominant majority culture, which bought most movie tickets and financed all Hollywood productions, and only one foot in the changing Black community, the superstar never shed his turn-the-other-cheek, Civil Rights skin to successfully evolve into a more assertive, empowered persona that connected with theatergoers.

Poitier never resolved the contradictions engendered by a new “Black and Proud” nationalist sense of self and ethnic pride. And after the upsurge of the “We-Shall-Overcome” and Black Power periods from the 1950s to the 1970s had subsided, and Reaganism reigned, there was less of a demand for Black-themed films and stars. President Reagan’s racial rants about “welfare queens” replaced Blaxploitation characters such as Pam Grier as Coffy and Foxy Brown or Tamara Dobson as Cleopatra Jones or Vonetta McGee as Blacula’s wife and the Angela Davis-like political prisoner in 1977’s Brothers.

As the current iteration of America’s racial reckoning unfolds, it is up to Black artists of today, such as Daniel Kaluuya, who won an Oscar for portraying a Black Panther revolutionary in Judas and the Black Messiah, Michael B. Jordan who was in the Africa-set Black Panther superhero blockbuster, directors Spike Lee and Ava DuVernay, et al., to complete the image arc in the 21st century that Sidney Poitier helped launch in 1950.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @globalresearch_crg. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Ed Rampell is an L.A.-based film historian and critic who also also reviews culture, foreign affairs and current events. Ed can be reached at [email protected].

Featured image: Sidney Poitier in his glory days. [Source: achievement.org]