The War on Gaza: A New Global Order in the Making? Part XIII-B

Part XIII-B

[Links to Parts I to XIII-A are provided at the bottom of this article.]

“If the United Nations once admits that international disputes can be settled by using force, then we will have destroyed the foundation of the organization and our best hope of establishing a world order.” (Dwight D. Eisenhower)

1. International Law or ‘Rules-based International Order’?

On 8 March 1992, The New York Times published excerpts from the Pentagon’s draft of the Defense Planning Guidance for the Fiscal Years 1994-1999. This important piece of archive addressed the “fundamentally new situation which has been created by the collapse of the Soviet Union, the disintegration of the internal as well as the external empire, and the discrediting of Communism as an ideology with global pretensions and influence”. The new international environment, it was explained, has “also been shaped by the victory of the United States and its coalition allies over Iraqi aggression – the first post-cold-war conflict and a defining event in U.S. global leadership.”

The drafters of this “Guidance” stated that the United States’ first objective should be “to prevent the re-emergence of a new rival, either on the territory of the former Soviet Union or elsewhere, that poses a threat on the order of that posed formerly by the Soviet Union. This is a dominant consideration underlying the new regional defense strategy and “requires that we endeavor to prevent any hostile power from dominating a region whose resources would, under consolidated control, be sufficient to generate global power. These regions include Western Europe, East Asia, the territory of the former Soviet Union, and Southwest Asia.” And the second objective is “to address sources of regional conflict and instability in such a way as to promote increasing respect for international law, limit international violence, and encourage the spread of democratic forms of government and open economic systems.” They also acknowledged that while the U.S. cannot become the world’s “policeman”, by assuming responsibility for righting every wrong, the U.S. will “retain the pre-eminent responsibility for addressing selectively those wrongs which threaten not only our interests, but those of our allies or friends, or which could seriously unsettle international relations”. They furthermore determined the various types of U.S. interests involved in such instances as being: access to vital raw materials, primarily Persian Gulf oil; proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and ballistic missiles; threats to U.S. citizens from terrorism or regional or local conflict; and threats to U.S. society from narcotics trafficking.”

As a matter of fact, during the whole decade of the 1990s, as the tumultuous twentieth century shuddered toward its close, the global geopolitical landscape was overwhelmingly dominated by a much-heated American internal debate about a big question: will America strive to dominate the world, or lead it?

This topic was the object of an influential book[1] written by Zbigniew Brzezinski, former National Security Advisor under President Jimmy Carter. In it, he reminded Americans that their might should not be confused with omnipotence, and their well-being and the world’s are entwined. He explained that panicky preoccupation with “solitary American security, an obsessively narrow focus on terrorism, and indifference to the concerns of a politically restless humanity neither enhance American security nor comport with the world’s real need for American leadership.” The conclusion Brzezinski then quite logically drew was that “unless it can harmonize its overwhelming power with its seductive but also unsettling social appeal, America could find itself alone and under assault in a setting of intensifying global chaos.”

Such a conclusion was all the more logical, accurate and timely as America – and the world with it – found themselves at the turn of the new millennium in an unprecedented state of disarray in the wake of the 2001 September 11th attacks. These led, among other epochal events, to the American blunders of Afghanistan and Iraq invasions in 2001 and 2003 respectively whose adverse consequences the world at large is still suffering from.

It is equally worthwhile to recall that when G. W. Bush took office in 2000, he brought with him Vice President Dick Cheney, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, and Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, all of whom had served together in Ronald Reagan’s and G. H. Bush’s administrations. In 1992, while he was in the Defense Department, Wolfowitz – long recognized as the intellectual force behind a radical neoconservative fringe of the Republican Party – was asked to write the first draft of a new National Security Strategy, a document entitled “The Defense Planning Guidance”.[2] The most controversial elements of that strategy were that the United States: should dramatically increase its defense spending; be willing to take preemptive military action; and be willing to use military force unilaterally, with or without allies.

Out of power during the Clinton administration, Wolfowitz and his colleagues presided over the creation, in 1997, of the Neoconservative think tank called “Project for a New American Century” (PNAC), which was placed under the chairmanship of William Kristol, the “Godfather” of American neoconservatism. And as soon as it was brought back to power within the G. W. Bush’s administration in 2000, Wolfowitz’s team got involved in shaping the U.S. neoconservative foreign policy, whose main principles were laid down in a defining document titled “Rebuilding America’s Defenses: Strategy, Forces and Resources for a New Century”.[3] This 90-page document was written in September of 2000, a full year before the 9/11 attacks.

Interestingly enough, in its section V entitled “Creating Tomorrow’s Dominant Force”, it stated that “the process of transformation, even if it brings revolutionary change, is likely to be a long one, absent some catastrophic and catalyzing event – like a new Pearl Harbor”. One year later, that event would indeed happen, and two decades later, the most important question of “what did really happen on September 11, 2001?” remains unanswered. Was it the result of a needed conspiracy to execute a premeditated plan? Or was it a mere coincidence exploited by believers in conspiracy theories? Only time will tell. However, what History has already recorded for sure is that this catastrophic event brought about equally catastrophic consequences, both intended and unintended, for America itself, for the Arab and Islamic world, and for the entire world.

In hindsight, Brzezinski’s 2004 assessment and expectations represented something of an unexpected 180-degree turn compared to his previous well-known ideological and geostrategic attitude and writings. In effect, only seven years before, he had written a hugely authoritative book[4] in which he outlined a strategy entirely based on the oft-cited phrase of Sir Halford J. Mackinder, who is generally considered the founding father of geopolitics: “Who rules Eastern Europe rules the continental heart; who rules the continental heart rules the world-island; who rules the world-island rules the world”.[5] Brzezinski argued that the last decade of the twentieth century witnessed a tectonic shift in world affairs:

“For the first time, a non-Eurasian power rose not only to the position of a key arbiter of relations among the states of Eurasia, but also to the position of the dominant global power. The defeat and fall of the Soviet Union completed the rapid rise of a northern hemisphere power, the United States, as the sole and, indeed, the first truly global power. Eurasia, however, retains its geopolitical importance. Not only does its western periphery – Europe – still hold much of the world’s political and economic power, but its eastern region – Asia – has recently become a center of vital economic growth and growing political influence.” That said, the ability of the United States to effectively and sustainably exercise global primacy will depend entirely on how it manages its complex relationships with the powers of this region, and particularly on the absolute imperative of “preventing the emergence of a dominant and antagonistic Eurasian power.”

In a language strongly reminiscent of that of “The Prince” of Niccolò Machiavelli, Brzezinski first specifies that in the blunt terminology of past empires, the three great geostrategic imperatives would be summarized as follows: “Avoid collusion with vassals and maintain them in the state of dependence justified by their security; cultivate the docility of protected subjects; prevent barbarians from forming offensive alliances.” He then advocates, on this basis, a strategy of unilateral domination, which had been called for before him by neoconservative ideologues and would later be adopted as a line of conduct during the terms of George W. Bush.

The essential point to keep in mind, Brzezinski says – giving sense to current events in Ukraine – is that

“Russia cannot be in Europe without Ukraine being there as well, while Ukraine can be in Europe without Russia being there (…) Ukraine, a new and important space on the Eurasian chessboard, is a geopolitical pivot because its very existence as an independent country helps to transform Russia. Without Ukraine, Russia ceases to be a Eurasian empire. Russia without Ukraine can still strive for imperial status, but it would then become a predominantly Asian imperial state (…) However, if Moscow regains control over Ukraine, with its 52 million people and major resources as well as its access to the Black Sea, Russia automatically again regains the wherewithal to become a powerful imperial state spanning Europe and Asia. Ukraine’s loss of independence would have immediate consequences for Central Europe, transforming Poland into the geopolitical pivot on the eastern frontier of a united Europe.”

In the final analysis, and contrary to Brzezinski’s “updated” wishes and predictions, America succeeded in being neither the guarantor of its own and the world’s security nor the promoter of the global common good. Far from it. What the United States effectively did is what all states normally do, as Lord Palmerston once famously proclaimed[6] – most probably having in mind the United States precisely – that’s to say to pursue their interests.

And while Brzezinski seemed to make amends in this respect, many other scholars and ideologues were advocating for American empire. Renowned economist Deepak Lal for one, also in 2004, wrote a controversial book[7] in which he laid out a historical and cross-civilizational examination of the role empires have played to provide the order required for peace and prosperity, and how this imperial role “has come to be thrust on the United States.” Expressing wish fulfillment for America of the exact same Virgil’s hope for Rome, Lal argued that “if the U.S. public does not recognize the imperial burden that history has thrust upon it, or is unwilling to bear it, the world will continue to muddle along as it has for the past century – with hesitant advances, punctuated by various alarms and by periods of backsliding in the wholly beneficial processes of globalization. Perhaps, if the United States is unwilling to shoulder the imperial burden of maintaining the global pax, we will have to wait for one or other of the emerging imperial states – China and India – to do so in the future.” Till then, he concluded, “we may be fated to live with the ancient Chinese curse, ‘May you live in interesting times.’”

To be sure, since its founding, the United States has consistently pursued a grand strategy focused on acquiring and maintaining preeminent power over various rivals, first on the North American continent, then in the Western hemisphere, and finally globally. During the Cold War, this strategy was manifested in the form of “containment”, which provided a unifying vision of how the United States could protect its systemic primacy as well as its security, ensure the safety of its allies, and eventually enable the defeat of its adversary, the Soviet Union. This is exactly what a 2015 Council on Foreign Affairs (CFR) report stated.[8]

Unlike the March 1992 “Guidance” which rarely, if ever, mentions China as being a rival or a foe, CFR’s President, Richard Haas – who has written the forward part of this report – concurs with the authors’ conclusion according to which “Of all the nations – and in most conceivable scenarios – China is an and will remain the most significant competitor to the United States for decades to come.”

Said omission of China in previous similar literature is also explained in the report by the fact that

“the American effort to ‘integrate’ China into the liberal international order has now generated new threats to U.S. primacy in Asia – and could eventually result in consequential challenge to American power globally.”

In reality, behind those openly expressed fears and criticism, lies an undisclosed threat that perhaps supersedes all others. That is the fact that Beijing’s domestic policies that have succeeded in transforming China from an impoverished nation into a world superpower, in a relatively short period of time – more precisely thanks to the reforms implemented by Deng Xiaoping since 1978, after Mao Zedong’s death in 1976 – have been performed within a paradigm that does not fully comply with the conventional fundamental Western liberal values and recipes. Those policies are thought to have contributed to an “economic miracle” distinctively characterized by an eightfold growth in gross national product over two decades. This prompted Joshua Cooper Ramo in 2004 to coin the term “Beijing Consensus”,[9] a moniker that nods to the “Washington Consensus” whose set of political and economic development prescriptions severely impacted the socio-economic situation of so many developing countries, especially in Latin America in the late 1980s.[10]

Hence, the overarching argument for China’s ideological threat to the West in general and the United States in particular is that China’s prodigious and rapid growth is providing an attractive alternative development model for the Global South, thereby signaling a challenge to American soft power. Stefan Halper argued in his 2010 book[11] that the “net effect of these developments is to reduce Western and particularly American influence on the global stage – along both economic and ideational axes.”

In the face of the challenge represented by the meteoric growth of the Chinese economy and its military power, Washington thus needs “a new grand strategy that centers on balancing the rise of Chinese power rather than continuing to assist its ascendancy.” This strategy, the report goes on to say, cannot be built on a bedrock of containment, as earlier effort to limit Soviet power was, because of the current realities of globalization.” And short of a “fundamental collapse of the Chinese state [that] would free Washington from the obligation of systematically balancing Beijing”, even the alternative of a “modest Chinese stumble would not eliminate the dangers presented to the United States in Asia and beyond”, and would constitute a serious threat to the U.S.-dominated international order.

The “Chinese challenge” continues unabated to haunt the American security establishment – which is largely autonomous and operates behind a wall of secrecy – lending additional credence and great contemporary relevance to the prescient views put forward by French Alain Peyreffitte in his 1973 essay.[12] Indeed, in 2021 the Atlantic Council published a paper titled “Global Strategy 2021: An Allied Strategy for China”.[13] It was prepared in collaboration with policy planning officials and strategy experts from ten “leading democracies”.[14] Its forward part was written by none other than Joseph S. Nye, who has coined the term “soft power” in the late 1980s, before circling the globe and coming into widespread usage following an article he wrote in 1990 in Foreign Policy magazine.[15]

The strategy states that

“China is the foremost geopolitical threat to the rules-based international system since the end of the Cold War, and the return of great-power rivalry will likely shape the global order for decades to come. Likeminded allies and partners need to take deliberate and coordinated action to strengthen themselves and counter the threat China poses, even as they seek longer-term cooperation with Beijing.” The Free world, the concluding remarks read, has “an impressive record of accomplishment in defeating challenges from autocratic great-power rivals and constructing a rules-based system.”, and by pursuing this strategy “with sufficient political will, resilience, and solidarity”, they can “once again outlast an autocratic competitor and provide the world with future peace, prosperity, and freedom.”

In contrast to other similar previous papers, one sentence is repeated time and again in this strategy, namely “the rules-based system”. It has since become the alpha and omega of American – and British – officials, academics, and media pundits.

For example, as recounted by John Dugard in a particularly insightful study,[16] President Biden published an op-ed[17] about Ukraine in the New York Times in which he declared that Russia’s action in Ukraine “could mark the end of the rules-based international order and open the door to aggression elsewhere, with catastrophic consequences the world over”.[18] There is no mention of international law. Later, in a press conference at the conclusion of the June 2022 NATO Summit Meeting in Madrid, he warned both Russia and China that the democracies of the world would “defend the rules-based order” (RBO). Again, there is no mention of international law. On 12 October 2022 the US President published a National Security Strategy which makes repeated reference to the RBO as the “foundation of global peace and prosperity”, with only passing reference to international law.[19]

So, what is this RBO “creature”, that American political leaders have increasingly invoked since the end of the Cold War instead of international law? Is it a harmless synonym for international law, as suggested by European leaders? Or is it something else, a system meant to replace international law which has governed the behavior of states for over 500 years?

The RBO may be seen as the United States’ alternative to international law, an order that encapsulates international law as interpreted by the United States to accord with its national interests, “a chimera, meaning whatever the US and its followers want it to mean at any given time”.[20] Premised on “the United States’ own willingness to ignore, evade or rewrite the rules whenever they seem inconvenient’,[21] the RBO is seen to be broad, open to political manipulation and double standards, and “seems to allow for special rules in special – sui generis – cases”.[22]

According to Dugard and many other scholars who have studied this subject, the rationale behind the reference by Washington to the RBO rather than to international law is that the U.S. is not a party to a number of important multilateral treaties and other legal instruments that constitute the backbone of international law as it is commonly known, including some fundamental legal instruments governing international humanitarian law.[23]

And as it relates to the War on Gaza, the rationale is that the United States is unwilling to hold some states, such as Israel, accountable for violations of international law. They are “treated as sui generis cases in which the national interest precludes accountability.” This exceptionalism in respect of Israel was spelled out by the United States in its joint declaration with Israel on the occasion of President Biden’s visit to Israel in July 2022,[24] which reaffirms “the unbreakable bonds between our two countries and the enduring commitment of the United States to Israel’s security” and the determination of the two states “to combat all efforts to boycott or de-legitimize Israel, to deny its right to self-defense, or to single it out in any forum, including at the United Nations or the International Criminal Court.”

This commitment explains the consistent refusal of the United States to hold Israel accountable for its repeated violations of humanitarian law, support the prosecution of perpetrators of international crimes before the International Criminal Court, condemn its assaults on Gaza, insist that Israel prosecute killers of a US national (journalist Shireen Abu Akleh), criticize its violation of human rights as established by both the Human Rights Council and the General Assembly, accept that Israel applies a policy of apartheid in the Occupied Palestinian Territory,[25] and oppose its annexation of East Jerusalem. And, of course, there is the refusal of the United States to acknowledge the existence of Israel’s nuclear arsenal or allow any discussion of it in the context of nuclear proliferation in the Middle East.[26] Such measures on the part of Israel are possibly seen as consistent with the “rules-based international order” even if they violate basic rules of international law.

Image: Sergey Lavrov

The RBO has been routinely criticized by Russia and China. Thus, in 2020 Sergey Lavrov, the Russian foreign minister, declared that the West advocated a “West-centric rules-based order as an alternative to international law with the purpose of replacing international law with non-consensual methods for resolving international disputes by bypassing international law.”[27] He further explained that the RBO was coined to “camouflage a striving to invent rules depending on changes in the political situation so as to be able to put pressure on disagreeable States and even on allies.” And again, on 25 May 2022 Lavrov, on the occasion of Africa Day, read out a statement by President Putin in which he declared in the context of Russia’s action in Ukraine that: “The main problem is that a small group of US-led Western countries keeps trying to impose the concept of a rules-based world order on the international community. They use this banner to promote, without any hesitation, a unipolar model of the world order where there are “exceptional” countries and everyone else who must obey the “club of the chosen”.[28]

As for China, its foreign minister Wang Yi stated in 2021, at a virtual debate of the UN Security Council on the theme of multilateralism, that “International rules must be based on international law and must be written by all. They are not a patent or privilege of a few. They must be applicable to all countries and there should be no room for exceptionalism or double standards.”[29]

2. The “Global South”: From Fence-Sitter to Arbiter?

The existing world order is at an inflection point, and the times ahead will likely be radically different from those experienced in our lifetimes and will determine the course of decades to come. The last similar epochal circumstances in recent history occurred between 1930 and 1945 and between 1999 and 2008. In both periods a confluence of peculiar political, economic, social, and cultural conditions led to fundamental shifts in world order; and in both instances such conditions paved the way for American leadership, or more accurately, global primacy.[30]

In the currently changing global strategic environment, opposition to and disapproval of the RBO – due to its incompatibility with international law as enshrined in the UN charter, multilateral treaties, and customary rules – are not exclusive to a resurging Russia and a rising China. They also have been, and still are being voiced by an increasing number of emerging countries of a more assertive Global South, determined to play its legitimate part and have a say in the governance of world affairs.

Moreover, the West’s – and especially the US’– support for Israel’s genocide in Gaza, in blatant violation of international and humanitarian law, when combined with condemnation of and imposition of immediate and unprecedented sanctions on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine, proves that the RBO talk is sheer hypocrisy, thereby immensely complicating the West’s position in the battle of narratives and global influence it is engaging with Russia and China.

As I referred to earlier, the essential narrative of the West is built into the U.S. national security strategy, the core idea of which is that China and Russia are implacable foes that are “attempting to erode American security and prosperity” and are determined “to make economies less free and less fair”, and “to control information and data to repress their societies and expand their influence.”

The irony, as remarked by Prof. Jeffrey Sachs – who has served as adviser to three UN Secretaries-General, and is currently serving as a Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Advocate under Secretary-General António Guterres – is that

“since 1980 the US has been in at least 15 overseas wars of choice (Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Panama, Serbia, Syria, and Yemen just to name a few), while China has been in none, and Russia only in one (Syria) beyond the former Soviet Union. The US has military bases in 85 countries, China in 3, and Russia in 1 (Syria) beyond the former Soviet Union.”[31]

The same irony is also manifested in the unconvincing West’s mantra that it is opposing dictatorships and championing freedom, human rights and democracy around the world. No wonder the Global South sees hypocrisy in the US’s framing of its hostility to and competition with such countries as China, Russia, Iran and North Korea – regularly singled out in successive National Security Strategies and lumped together in an “Axis of Upheaval”[32] – as a battle between democracy and autocracy. How else can one explain the fact that Washington continues to support many “undemocratic” and even “dictatorial” regimes and governments, selectively providing them with multifaceted aid and assistance?

Indeed, according to Freedom House, as of fiscal year 2015 the U.S. government has been providing military assistance to 36 of the 49 nations the NGO counts as dictatorships”, a percentage of 73%! In 2021, this proportion had not changed since 35 out of 50 continued to receive such aid. Worst still, Freedom House informed[33] that during the same period, as COVID-19 spread, “governments across the democratic spectrum repeatedly resorted to excessive surveillance, discriminatory restrictions on freedoms like movement and assembly and arbitrary or violent enforcement of such restrictions by police and non-state actors. Waves of false and misleading information, generated deliberately by political leaders in some cases, flooded many countries’ communication system, obscuring reliable data and jeopardizing lives.” Also, and inevitably, the “parlous state of US democracy” did not go unnoticed; it was conspicuous in the early days of 2021 as an “insurrectionist mob, egged on by the words of outgoing president Donald Trump and his refusal to admit defeat in the November election”, stormed the Capitol building, the symbolic heart of US democracy. The United States, the NGO advised, will need “to work vigorously to strengthen its institutional safeguards, restore its civic norms, and uphold the promise of its core principles for all segments of society if it is to protect its venerable democracy and regain global credibility.” All these withering blows marked the 15th consecutive decline in global freedom, the NGO lamented.

An answer to this big and troubling question of the U.S. relations with authoritarian countries was given in a thoroughly-researched study[34] published by Carnegie Endowment for international Peace in 2023. The paper reached three overarching conclusions:

First, Biden’s policy with regard to authoritarian countries represents, on the whole, more continuity with than change from most previous U.S. presidents, reflecting deep structures of interest that have shaped U.S. relations with these countries for decades.

Second, security issues are the dominant driver of U.S. relations with authoritarian countries – for both positive and negative relations – and span a wide range of security concerns, including competition with China and Russia, terrorism, and regional instability. Economic interests – such as energy investments, critical minerals, arms sales, or ensuring U.S. market access – also play a role in spurring positive U.S. relations with some authoritarian states, but overall are far less important than security concerns. Therefore, when the United States has a clear security interest in maintaining friendly relations with an authoritarian country, concerns about democracy are usually on the back burner, if not absent entirely.

Third, the trends going forward appear to be mixed. With U.S.-China and U.S.-Russia tensions continuing to escalate, “the United States will have more reasons to put aside its concerns about democracy and human rights in some authoritarian countries as it tries to convince them to move closer to its camp. It will also be motivated to turn a cold shoulder to other countries that align themselves with its rivals.”

The Carnegie study points to the fact that many people in U.S. policy circles debate the wisdom of the administration’s trade-offs between its stated interest in supporting democracy globally versus countervailing interests that lead it to maintain close ties with some autocrats. But these debates are often confined to a few high-profile cases and rarely draw from a broader understanding of the overall landscape of U.S. relations with authoritarian regimes and the trajectory of such relations across recent decades.

The authors of the paper conclude by saying that Washington’s policy “produces justifiable charges of hypocrisy among observers around the world who see a U.S. administration apply the principle and deliver generous doses of self-righteous rhetoric in one country and then completely ignore democracy and rights issues in another.”

With regard to the Ukraine war, the West’s narrative is that it is a brutal and unprovoked attack by Vladimir Putin in his quest to recreate the Russian empire. Yet the real story of what caused the crisis is the Western promise to the reformist President Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO would not enlarge to the east. “Not one inch eastward”[35] was the assurance given by US Secretary of State James Baker to Gorbachev on February 9th, 1990. What has followed, however, is a wave of aggrandizements that concerned former members of the defunct Warsaw Pact and two Scandinavian nations as of late: three in 1999, seven in 2004, two in 2009, one in 2017 and 2020, and one in 2023 (Finland) and 2024 (Sweden), in addition to the 2008 commitment to incorporate Georgia and Ukraine – two countries in the immediate vicinity of Russia. Since the Alliance was created in 1949, its membership has thus grown from the 12 founding members to today’s 32 members.

.

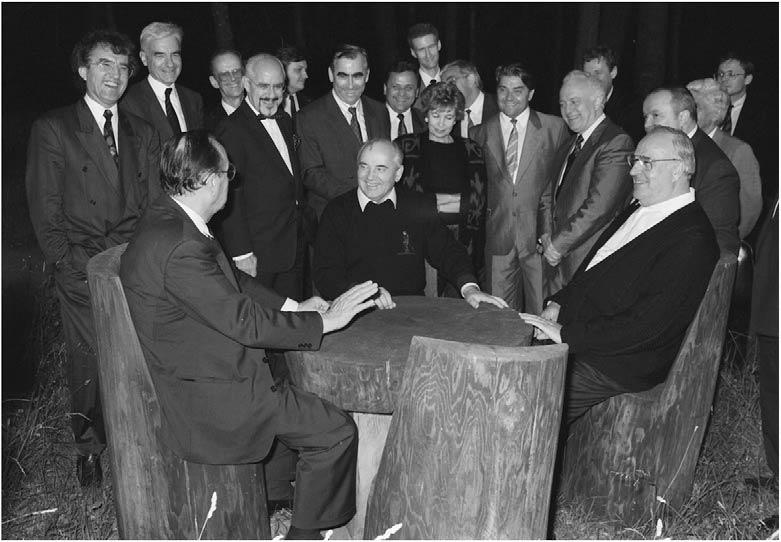

Michail Gorbachev discussing German unification with Hans-Dietrich Genscher and Helmut Kohl in Russia, July 15, 1990. Photo: Bundesbildstelle / Presseund Informationsamt der Bundesregierung.

.

All this despite early warnings emanating from very experienced U.S. diplomats. In fact, on 5 February 1997, diplomat-historian George Kennan did not mince words in arguing that “expanding NATO would be the most fateful error in American policy in the entire post-cold war era. Such a decision may be expected… to impel Russian foreign policy in directions decidedly not to our liking.”[36] And one year later, on 1 February, William Burns – then U.S. ambassador in Moscow and now CIA Director – sent a confidential cable to Washington D.C., which he titled “Nyet Means Nyet: Russia’s NATO Enlargements Redlines”. The main part of that famous cable read: “Ukraine and Georgia’s NATO aspirations not only touch a raw nerve in Russia, they engender serious concerns about the consequences for stability in the region. Not only does Russia perceive encirclement, and efforts to undermine Russia’s influence in the region, but it also fears unpredictable and uncontrolled consequences which would seriously affect Russian security interests. Experts tell us that Russia is particularly worried that the strong divisions in Ukraine over NATO membership, with much of the ethnic-Russian community against membership, could lead to a major split, involving violence or at worst, civil war. In that eventuality, Russia would have to decide whether to intervene; a decision Russia does not want to have to face.”[37]

President Valdimir Putin also sent strong messages to the West at least on three occasions: in his speech at the Munich Security Conference in 2007 where he denounced the U.S.-led unipolar order; through his war against Georgia, at the end of which Tbilisi lost Abkhazia and South Ossetia in 2008; and finally with the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Retrospectively, one may conclude that those messages have been inadequately understood, to put it mildly.

Back in 2022, John Mearsheimer said in this regard that

“My argument is that the West, especially the United States, is principally responsible for this disaster. But no American policymaker is going to acknowledge that line of argument. So they will say the Russians are responsible.”[38] More recently, he reiterated this same conviction in a conference titled “The Causes and Consequences of the Ukraine Crisis”.[39]

For all these main reasons and others, Jeffrey Sachs was perfectly right to conclude that

“Europe should reflect on the fact that the non-enlargement of NATO and the implementation of the Minsk II agreements would have averted this awful war in Ukraine”, and that “It’s past time that the US recognized the true sources of security: internal social cohesion and responsible cooperation with the rest of the world, rather than the illusion of hegemony.”

With such a revised foreign policy, he added, the US and its allies would avoid war with China and Russia, and enable the world to face its myriad environment, energy, food and social crises.[40]

Sachs’s good advice is precisely what China in particular has been advocating and applying through a series of eye-catching initiatives aimed at increasing its power and boosting its diplomatic clout and global prestige to fulfil President Xi Jinping’s “Chinese Dream” vision, all the while countering Western hegemony.

On that account, Beijing launched the “Belt and Road Initiative” (BRI) in 2013, the “Community of Shared Future of Mankind” in 2015, the “Global Development Initiative” (GDI) in 2021, and the “Global Security Initiative” (GSI) in 2022. Moreover, in light of President Biden’s “Democracy vs. Authoritarianism” narrative and ahead of the second Summit for Democracy,[41] President Xi Jinping announced the “Global Civilization Initiative” (GCI).[42] At the Communist Party of China’s “Dialogue with World Political Parties High-level Meeting”, he said that the initiative will allow nations worldwide to adopt a new type of modernization and development and assist them in having a firm hold on their future development and progress.[43] He also declared that China wants other nations to uphold the principle of equality, have an open mindset, refrain from imposing its values and models, and build a global network for inter-civilizational dialogue and cooperation.

As a result of this frantic battle of narratives, today more than ever the Global South is being courted by both sides, hence finding itself in an historically favorable condition to pursue its own interests, which have, for too long, been cynically disregarded by too often condescending world’s great powers. And the answer to the important question of which direction the majority of the Global South’s countries and public opinion will be tipped seems to be embodied in the compelling fact that bold actions and initiatives are being undertaken together with China and Russia, not with the West.

Among other significant common undertakings that signal a new age of international relations ushering the world into a multipolar global order is the creation of the BRICS group in 2009 and the “Group of Friends in Defense of the Charter of the United Nations” in 2021.

.

The plenary session of the Outreach/BRICS Plus meeting. (By Alexei Danichev / Photohost agency brics-russia2024.ru)

.

Named after its five founding members (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), the BRICS group is a collective of emerging economies eager to sustain and improve their economic trajectory. The four fundamental values and principles that underpin this non-Western grouping are: economic development, multilateralism, global governance reform, and solidarity.

The inclusion of Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, and the United Arab Emirates in the 16th BRICS Summit in Kazan, Russia, in October 2024 formally marked its expansion. During that Summit convened under the theme “Strengthening Multilateralism for Just Global Development and Security”, the leaders of the member states commended the Russian chairship for hosting an “Outreach”/ BRICS Plus” Dialogue with participation of emerging developing countries from Africa, Asia, Europe, Latin America, and Middle East under the motto: “BRICS and Global South: Building a Better World Together”. Almost three dozen more countries – including NATO member Türkiye, close US partners Thailand and Mexico, and Indonesia, the world’s largest Muslim country – have applied to join the henceforth BRICS+.

The group now dwarfs the Western G7, both demographically (46% of the world’s population, compared with the G7’s 8.8%) and economically (35% of global GDP, compared to the G7’s 30%). It also has the potential “to serve as a catalyst for a long-overdue revamping of global governance so that it better reflects twenty-first-century realities.”[44]

As far as the “Group of Friends of the Charter of the United Nations” (GoF), so far composed of 18 member states[45], it concurs that “one of the key elements for ensuring the realization of the three pillars of the Organization of the United Nations and of the yearnings of its peoples, as well as of a peaceful and prosperous world and a just and equitable world order, is ensuring precisely, compliance with and strict adherence to the purposes and principles enshrined in the Charter, for it is the consolidation of relations and cooperation among States that will ensure peace, security, stability and development to the international community as a whole.” It, however, considers that multilateralism, which is at the core of the Charter, is currently under an unprecedented attack, which, in turn, threatens global peace and security.

The GoF members also reject the attempt to establish a RBO. On the occasion of the first meeting of national coordinators of the GoF held in Tehran, Iran, on 5 November 2022, the participants reiterated their “serious concern” at continued attempts aimed at replacing the tenets enshrined in the UN Charter, which have been agreed upon by the entire international community for conducting their international relations, with a “so-called ‘rules-based order, that remains unclear, “that has not been discussed or accepted by the wide membership”, and that has the “potential, among others, to undermine the rule of law at the international level”. Further, they called for the redoubling of efforts toward “democratization of international relations”, the “strengthening of multilateralism and of a multipolar system”, while expressing their “categorical rejection of all unilateral coercive measures, including those applied as tools for political or economic and financial pressure against any country, in particular against developing countries.”

It is worth recalling that the GoF’s initial creation came shortly after the U.S. and a number of its allies and partners supported Venezuelan opposition-controlled National Assembly head’s claim to the presidency in defiance of President Nicolás Maduro, who stood accused of engineering his win at the elections, and that the group’s recurrent calls for additional membership come amid renewed great power competition between the U.S. and its top rivals, China and Russia.[46]

In 2023, just a few months before the wreckage of the international and humanitarian law in the mass killing fields of Gaza, Foreign Affairs magazine’s executives had the good idea of devoting much of the May/June issue[47] to the topic of the state of world order. On that occasion, several policymakers and scholars from Africa, Latin America, and South and Southeast Asia were invited to explore the dangers, as well as the new opportunities, that the war in Ukraine and the broader return of great-power conflict present for their respective countries and regions.

The overarching conclusion of the different contributors was that Russia’s war in Ukraine has drawn Western allies together, but it has not unified the world’s democracies in the way U.S. President Joe Biden might have hoped for when the war started. Instead, the unfolding events highlighted just how different much of the rest of the world sees not only the war but also the broader global landscape.

Voicing the point of view of Africans, South African Prof. Tim Murithi[48] pointed out that many African countries declined to take a strong stand against Moscow, and more and more nations in the continent and elsewhere in the Global South are refusing to align with either the West or the East, “declining to defend the so-called liberal order but also refusing to seek to upend it as Russia and China have done.” The reason for that, Murithi argues, is that the rules-based international order has not served the African interests. On the contrary, it has preserved a status quo in which major world powers, be they Western or Eastern, have maintained their positions of dominance over the Global South, relegated African governments to “little more than bystanders in their own affairs”, and ignored their longstanding calls for the UN Security Council to be reformed and the broader international system to be reconfigured on more equitable terms. If the West wants Africa to stand up for the international order, he says, then “it must allow that order to be remade so that it is based on more than the idea of might makes right.”

For Brazilian Prof. Matias Spektor[49], developing countries are increasingly seeking to avoid costly entanglements with the major powers, trying to keep all their options open for maximum flexibility; they are pursuing a strategy of hedging because they see the future distribution of global power as uncertain and wish to avoid commitments that will be hard to discharge. They hedge not only to gain material concessions but also to raise their status, and they embrace multipolarity as an opportunity to move up in the international order. If the United States wants to remain first among the great powers in a multipolar world, Prof. Spektor concludes, it “must meet the Global South on its own terms.”

For her part, Nirupama Rao[50], India’s Foreign Secretary from 2009 to 2011 and formerly ambassador to China and the United States, believes that India has “limited patience for U.S. and European narratives which are both myopic and hypocritical”, and although Europe and Washington may be right that Russia is violating human rights in Ukraine, “Western powers have carried out similar violent, unjust, and undemocratic interventions – from Vietnam to Iraq.” New Delhi is therefore uninterested in Western calls for Russia’s isolation. To strengthen itself and address the world’s shared challenges, Rao added, “India has the right to work with everyone.” This perspective isn’t unique to her country, and much of the Global South is wary of being dragged into siding with the U.S. against China and Russia. Developing countries, she rightly observes, are “understandably more concerned about their climate vulnerability, their access to advanced technology and capital, and their need for better infrastructure, health care, and education systems. They see increasing global instability – political and financial alike – as a threat to tackling such challenges. And they have watched rich and powerful states disregard those views and preferences in pursuit of their geopolitical interests.” That’s why Rao goes on to say, India “wants to make sure the voices of these poorer states are heard in international debates” and is positioning itself as “a heartland of global South – a bridging presence that stands for multilateralism.”

In a remarkably balanced piece he wrote in the same Foreign Affairs issue, former UK Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, David Miliband concurred with the views and legitimate demands of the “fence-sitting” Global South. It is to be hoped that Miliband’s fellow Western citizens will listen carefully to his message and, more importantly, heed his wise advice, because as he rightly highlighted in the subtitle of his contribution[51], what is also at stake in the present historical juncture is no less than “the survival of the West”.

*

Click the share button below to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Global Research’s Holiday Fundraiser

Amir Nour is an Algerian researcher in international relations, author of the books “L’Orient et l’Occident à l’heure d’un nouveau Sykes-Picot” (The Orient and the Occident in Time of a New Sykes-Picot) Editions Alem El Afkar, Algiers, 2014 and “L’Islam et l’ordre du monde” (Islam and the Order of the World), Editions Alem El Afkar, Algiers, 2021.

Notes

[1] Zbigniew Brzezinski, “The Choice: Global Domination or Global Leadership”, Basic Books, 2004.

[2] See this document which has been declassified under authority of the Interagency Security classification Appeal Panel https://www.archives.gov/files/declassification/iscap/pdf/2008-003-docs1-12.pdf

[3] Read the document on https://cryptome.org/rad.htm

[4] Zbigniew Brzezinski, “The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and its Geostrategic Imperatives”, Basic Books, 1997.

[5] Halford J. Mackinder, “Democratic Ideals and Reality”, Holt, New York, 1919.

[6] Twice UK Prime Minister (1855-58 and 1859-65) Lord Palmerston, also known as Henry John Temple, said before Parliament in 1848: “Therefore I say that it is a narrow policy to suppose that this country or that is to be marked out as the eternal ally or the perpetual enemy of England. We have no eternal allies, and we have no perpetual enemies. Our interests are eternal and perpetual, and those interests it is our duty to follow.”

[7] Deepak Lal, “In Praise of Empires: Globalization and Order”, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2004.

[8] Robert D. Black will and Ashley J. Tellis, “Revising U.S. Grand Strategy Toward China”, Council Special Report No. 72, March 2015.

[9] Joshua Cooper Ramo, “The Beijing Consensus”, The Foreign Policy Centre, 2004. Later on, in 2016, Ramo explained that the Beijing Consensus shows not that “every nation will follow China’s development model, but that it legitimizes the notion of particularity as opposed to the universality of a Washington model”. See Maurits Elen, “Interview: Joshua Cooper Ramo”, The Diplomat, August 2016.

[10] See Jhana Gottlieb, “The Beijing Consensus: A Threat of Our Own Creation”, Center for International Maritime Security, 22 April 2017.

[11] Stefan Hapler, “The Beijing Consensus: Legitimizing Authoritarianism in Our Time”, Basic Books, 2010.

[12] Alain Peyreffitte, “Quand la Chine s’éveillera… le monde tremblera” (When China Awakens… the World Will Tremble), Fayard, Paris, 1973. The essay’s main thesis is that given the size and growth of the Chinese population, it will inevitably end up imposing itself on the rest of the world as soon as it masters sufficient technology, and that “Today’s China only makes sense if we put it in perspective with yesterday’s China.” As for the title, it comes from a phrase attributed to Napoléon I: “Let China sleep, because when China awakens the whole world will tremble.” Napoléon would have uttered this sentence in 1816 in Saint Helena after reading “Voyage en Chine et en Tartarie” (Journey to China and Tartary) written by Lord George Macartney, Great Britain’s first envoy to China.

[13] To read the Strategy: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/global-strategy-2021-an-allied-strategy-forchina/#:~:text=cooperating%20within%2C%20rather,Government%0AHarvard%20University

[14] United States, Italy, Japan, Germany, Australia, India, France, Canada, UK, and South Korea.

[15] Joseph S. Nye, “Soft Power”, Foreign Policy No. 80. 1990: “These trends suggest a second, more attractive way of exercising power than traditional means. A state may achieve the outcomes it prefers in world politics because other states want to follow it or have agreed to a situation that produces such effects. In this sense, it is just as important to set the agenda and structure the situations in world politics as to get others to change in particular cases. This second aspect of power – which occurs when one country gets other countries to want what it wants – might be called co-optive or soft power in contrast with the hard or command power of ordering others to do what it wants.”

[16] John Dugard, “The choice before us: International law or a ‘rules-based international order’?”, Cambridge University Press, 21 February 2023.

17] Joe R. Biden Jr., “How the US Is Willing to Help Ukraine”, The New York Times International Edition, 2 June 2022.

[18] The White House Briefing Room, “Remarks by President Biden in Press Conference (Madrid, Spain)”, The White House, 30 June 2022, available at: www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2022/06/30/remarks-by-president-biden-in-press-conference-madrid-spain.

[19] The White House, “National Security Strategy”, The White House, October 2022. Available at: www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf.

[20] See further, R. Falk, “‘Rules-based International-Order’: A New Metaphor for US Geo-Political Primacy”, Eurasia Review, 1 June 2021, available at” www.eurasiareview.com; G. Cross, “Rules-based Order: Hypocrisy Masquerading as Principle”, China Daily, 3 May 2022, available at: www.chinadailyhk.com/article/269894#Rules-based-order-masquerading-as-principle.

[21] S. Walt, “China Wants a ‘Rules Based International Order’ Too”, Foreign Policy, 31 March 2021, available at: www.belfercenter.org/publication/china-wants-rules-based-international-order-too. See also A. Tuygan, “The Rules-based International Order”, Diplomatic Opinion, 10 May 2021, available at: www.diplomaticopinion.com/2021/05/10/the-rules-based-international-order/.

[22] S. Talmon, “Rules-based Order v International Law?”, German Practice in International Law, 20 January 2019, available at: www.gpil.jura.uni-bonn.de/2019/01/rules-based-order-v-international-law.

[23] Among others: the 1977 Protocols to the Geneva Conventions on the Laws of War, the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the 1989 Rights of the Child Convention, the 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Convention, the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, the 2006 Convention of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions.

[24] The White House Briefing Room, “The Jerusalem US-Israel Strategic Partnership Joint Declaration”, The White House, 14 July 2022, available at: www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/07/14/the-jerusalem-u-s-israel-strategic-partnership-joint-declaration/.

[25] B. Samuels, “The US State Department Rejects Amnesty’s Apartheid Claim against Israel”, Haaretz, 1 February 2022.

[26] V. Gilinsky and H. Sokolski, “Biden Should End US Hypocrisy on Israeli Nukes”, Foreign Policy, 19 February 2022.

[27] Cited in A. N. Vylegzhanin et al., “The Term ‘Rules-Based Order in International Legal Discourse’”, Moscow Journal of International Law 35, 2021.

[28] K. K. Klomegah, “Russia Renews its Support to Mark Africa Day”, Modern Diplomacy, 27 May 2022, available at: www.moderndiplomacy.eu/2022/05/27/russia-renews-its-support-to-mark-africa-day/.

[29] State Councilor and Foreign Minister W. Yi, ‘Remarks by State Councilor and Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the United Nations Security Council High-level Meeting on the Theme ‘Maintenance of International Peace and Security: Upholding Multilateralism and the United Nations-centered International System”’, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, 8 May 2021, available at: www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjdt_665385/zyjh_665391/202105/t20210508_9170544.html.

[30] See Ray Dalio, “Principles for Dealing with the Changing World Order: Why Nations Succeed and Fail”, Simon & Schuster, 2021.

[31] Jeffrey Sachs, “The West’s False Narrative about Russia and China”, 22 August 2022; available at: https://www.jeffsachs.org/newspaper-articles/h29g9k7l7fymxp39yhzwxc5f72ancr

[32] Andrea Kendall-Taylor and Richard Fontaine, “The Axis of Upheaval: How America’s Adversaries Are Uniting to Overturn the Global Order”, Center for a New American Security, 23 April 2024.

[33] Sarah Repucci and Amy Slipowitz, “Freedom in the World: Democracy under Siege”, Freedom House.

[34] Thomas Carothers and Benjamin Feldman, “Examining U.S. Relations With Authoritarian Countries”, The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 13 December 2023.

[35] To read the related declassified document: https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/russia-programs/2017-12-12/nato-expansion-what-gorbachev-heard-western-leaders-early

[36] George F. Kennan, “A Fateful Error”, The New York Times, 5 February 1997.

[37] This document, which was revealed Wikileaks.org, is available at: https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/08MOSCOW265_a.html\

[38] Cited in Isaac Chotiner, “Why John Mearsheimer Blames the U.S. for the Crisis in Ukraine”, The New Yorker, 1 March 2022.

[40] Jeffrey Sachs, “The West’s False Narrative about Russia and China”, Op Cit.

[41] See United States Department of State’s Presentation of the Summit at: https://www.state.gov/summit-for-democracy-2023

[42] Kashif Anwar, “Xi Jinping’s Global Civilization Initiative”, 22 April 2023.

[43] To read “Full text of Xi Jinping’s keynote address at the CPC in Dialogue with World Political Parties High-level Meeting”, Xinhua, 16 March 2023: https://english.news.cn/20230316/31e80d5da3cd48bea63694cee5156d47/c.html?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email

[44] Brahma Chellany, “The BRICS Effect”, Project Syndicate, 18 October 2024.

[45] Algeria, Belarus, Bolivia, China, Cuba, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, the Islamic Republic of Iran, the Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Mali, Nicaragua, the State of Palestine, the Russian Federation, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Syria, Venezuela, and Zimbabwe.

[46] Tom O’Connor, “China, Russia, Iran, North Korea and More Join Forces ‘in Defense’ of U.N.”, 3 December 2021.

[47] Foreign Affairs, “The Nonaligned world: The West, the Rest, and the New Global Disorder”, May/June 2023.

[48] Tim Murithi, “Order of Oppression: Africa’s Quest for an International System”.

[49] Matias Spektor, “In Defense of the Fence Sitters: What the West Gets Wrong About Hedging”.

[50] Nirupama Rao, “The Upside of Rivalry: India’s Great-Power Opportunity”.

[51] David Miliband, “The World Beyond Ukraine: The Survival of the West and the Demands of the Rest”.

Links to Parts I to XIII-A:

The War on Gaza: Might vs. Right, and the Insanity of Western Power

By , December 01, 2023

The War on Gaza: How the West Is Losing. Accelerating the Transition to a Multipolar Global Order?

By , December 04, 2023

The War on Gaza: Debunking the Pro-Zionist Propaganda Machine

By , December 11, 2023

The War on Gaza: Why Does the “Free World” Condone Israel’s Occupation, Apartheid, and Genocide?

By , December 22, 2023

The War on Gaza: How We Got to the “Monstrosity of Our Century”

By , January 25, 2024

The War on Gaza: Towards Palestine’s Independence Despite the Doom and Gloom

By , February 02, 2024

The War on Gaza: Whither the “Jewish State”?

By , April 17, 2024

The Twilight of the Western Settler Colonialist Project in Palestine

By , August 17, 2024

The War on Gaza: Perpetual Falsehoods and Betrayals in the Service of Endless Deception. Amir Nour

By , August 25, 2024

By , September 07, 2024

The War on Gaza: Requiem for the Deeply Held Two-State Delusion. Amir Nour

By , September 21, 2024

By , October 26, 2024

The War on Gaza: A New Global Order in the Making?

By , December 02, 2024