Power Play: The Future of Food

New Global Research e-Book

Power Play

The Future of Food

by

Colin Todhunter

Power Play: The Future of Food © 2024 by Colin Todhunter is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International. To view a copy of this licence, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/

This licence requires that reusers give credit to the creator. It allows reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form and for non-commercial purposes only.

BY: Credit must be given to the creator.

NC: Only non-commercial use is permitted. This means not primarily intended for or directed towards commercial advantage or monetary compensation.

ND: No derivatives or adaptations are permitted.

Cover image: Bags of chilli outside a wholesaler in the George Town area of Chennai in 2024 by the author. Emblematic of Chennai’s role as a major spice trading hub. Spices have been a cornerstone of South Indian commerce for centuries, and Chennai, with its strategic port location, has long been a key player in this trade. The prominence of chilli highlights its significance in South Indian cuisine and culture. While modern supermarkets and online platforms are changing consumer habits, wholesale markets like those in George Town continue to serve an essential function in the supply chain.

About the Author

Colin Todhunter is an independent researcher and writer and has spent many years in India. He is a research associate of the Centre for Research on Globalisation (Montreal) and writes on food, agriculture and development issues. In 2018, in recognition of his writing, he was named a Living Peace and Justice Leader and Model by Engaging Peace Inc.

𝐂𝐨𝐥𝐢𝐧 𝐓𝐨𝐝𝐡𝐮𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫 – Academia.edu

Endorsements

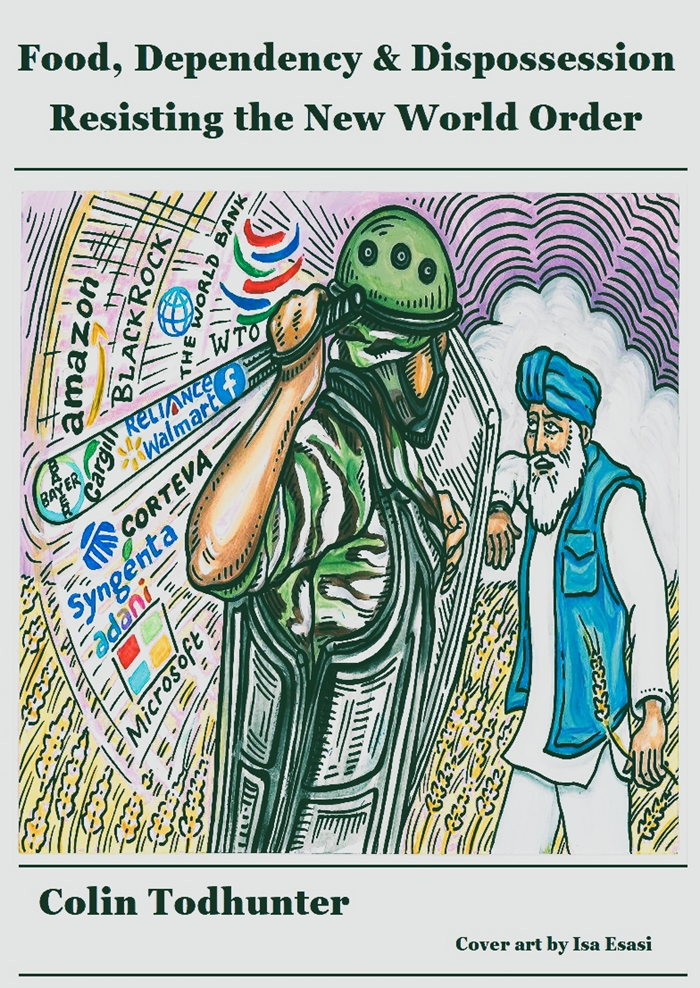

Aruna Rodrigues, lead petitioner in the GMO mustard Public Interest Litigation in the Supreme Court of India, stated the following about the author’s 2022 e-book Food, Dispossession and Dependency. Resisting the New World Order:

“Colin Todhunter at his best: this is graphic, a detailed horror tale in the making for India, an exposé on what is planned, via the farm laws, to hand over Indian sovereignty and food security to big business. There will come a time pretty soon — (not something out there but imminent, unfolding even now), when we will pay the Cargills, Ambanis, Bill Gates, Walmarts — in the absence of national buffer food stocks (an agri policy change to cash crops, the end to small-scale farmers, pushed aside by contract farming and GM crops) — we will pay them to send us food and finance borrowing from international markets to do it.”

Frederic Mousseau, Policy Director at the Oakland Institute, says the following about the author’s work:

“It takes a book to break down the dynamics that are pushing agro-chemical agriculture to farmers and consumers around the world and to reveal the strength of the diverse movement of people and organizations who stand in the way of these destructive and predatory forces.

“Colin Todhunter takes readers on a world tour that makes a compelling case against the fallacy of the food scarcity and Green Revolution arguments advanced by the mainstream media and international institutions on behalf of powerful financial interests such as Blackrock, Vanguard, or Gates. Todhunter makes it obvious that a key factor of world hunger and of the environmental crisis we are facing is a capitalist system that ‘requires constant growth, expanding markets and sufficient demand.’

“Uplifting rather than depressing, after this lucid diagnosis, he highlights some of the countless people-led initiatives and movements, from Cuba, Ethiopia to India, that fight back against destruction and predation with agroecology and farmers-led practices, respectful of the people and the planet. By debunking the “artificial scarcity” myth that is constantly fed to us, Todhunter demonstrates that it is actually not complicated to change course. Readers will just have to join the movement.”

Table of Contents

Introduction

Chapter I:

Consolidated Power

Chapter II:

Sick to Death

Chapter III:

Commodification of Farmland

Chapter IV:

Digital Panopticon and the Future of Food

Chapter V:

Manifesto for Corporate Control and Technocratic Tyranny

Chapter VI:

From Agrarianism to Transhumanism: Long March to Dystopia

Chapter VII:

Platforms of Control and the Unbreakable Spirit

Chapter VIII:

Ongoing Corporate Capture of Indian Agriculture

Chapter IX:

Amazon Gets Fresh, Bayer Loves Basmati

Chapter X:

From Monsanto to Bayer: Worst of Both Worlds

Chapter XI:

Bayer’s ‘Backward’ Claim: Bid for Control of Indian Agriculture

Chapter XII:

You Are Still the Enemy Within

Chapter XIII:

Reclaim the Future

Chapter XIV:

In 1649…

Introduction

This ebook provides insight into aspects of the global food system, including the micronutrient crisis, contested climate emergency rhetoric and its use in implementing the rollout of controlling technologies, the emergence and influence of digital platforms in shaping agricultural practices and the increasing corporate capture of Indian agriculture.

The book is the third installment in a trilogy of ebooks by the author exploring the global food system. It evolved from a series of articles originally published by various media outlets and written by the author and follows the February 2022 publication of Food, Dependency and Dispossession: Resisting the New World Order and the December 2023 release of Sickening Profits: The Global Food System’s Poisoned Food and Toxic Wealth.

When read together, the three books provide an overarching critique of contemporary food systems and possible solutions. For instance, the first book presents a more in-depth discussion of agroecology, the role of the Gates Foundation, the impact of pesticides, the state of agriculture in India, including the 2020-21 farmers protest, and the issue of development.

The second book touches on some of those issues but broadens the debate to look at ecomodernism, food-related ill health, the role of big finance in the food system and the post-Covid food crisis. While readers do not have to read the first two books, it might help in providing added context and insights.

This new book draws on and develops many of the themes presented in the first two. In particular, it returns to India to explore what has happened over the last 22 months (since the publication of the first book).

More generally, it looks at the intertwining of political centralisation and corporate consolidation that is undermining democratic processes, economic diversity and local autonomy. This unholy alliance is creating a self-reinforcing, technocratic dystopia that concentrates power in the hands of a super-wealthy elite, which increasingly depicts anyone who challenges it as the ‘enemy within’.

In this respect, the book weds the topic of food to the wider dynamics of power in society, which is becoming increasingly concentrated, resulting in the domination of both resources and populations and seeking to shape the very fabric of our lives and beliefs about who we are and what we could or should be. Such an analysis is integral to gaining a deeper understanding of the food system and the influence of global agribusiness and the tech giants that are increasingly moving into the food and agriculture sector.

The following discussion is driven by a conviction in the transformative power of re-localising food systems, revitalising traditional ecological wisdom and rekindling our connection to the land that nourishes us. At its core, it challenges us to question our understanding of human progress and development.

Chapter I:

Consolidated Power

By focusing on the nature of power and certain challenges and issues that we face, this introductory chapter establishes a foundational framework for what appears in the subsequent chapters.

We live in a world that sees political power becoming increasingly centralised. In turn, this creates an environment ripe for corporate influence. Large corporations, with their vast resources, can more easily focus their lobbying efforts and capture policymaking bodies at national and international levels than at a more fragmented local or regional level, leading to regulations and laws that favour big business over small enterprises and the needs and rights of ordinary people. This results in a landscape dominated by a handful of corporate giants, each wielding enormous economic and political clout.

This consolidation of corporate power further reinforces political centralisation, as wealthy corporations (for example, think big pharma and big agribusiness) can effectively dictate policy through campaign contributions, lobbying efforts and the revolving door between government and industry. The voice of the average citizen is drowned out by the influence of corporate power.

As a result of this corporate monopolisation, local markets and small businesses, once the backbone of communities, are being systematically crushed under the weight of centralised state-corporate power. Unable to compete with the economies of scale and political influence of large corporations, they are forced to close their doors or sell out to larger entities. This not only reduces choice and drives up prices but also strips communities of their unique character and economic self-determination.

The global interests served by this system are at odds with local needs and values. Decisions made in distant boardrooms and government offices fail to account for the nuanced realities of diverse communities. Environmental concerns are brushed aside in favour of short-term profits, while cultural traditions are homogenised to fit corporate needs.

Democratic processes, designed to give voice to the many, are subverted to serve the interests of the few. Real power resides in the hands of those who control the purse strings, and public discourse is shaped by the corporate media (often part of larger conglomerates), limiting the range of ideas and stifling dissent.

At the same time, when decision-making is concentrated in a few hands, the potential for catastrophic errors increases. Over-centralised, corporate-dominated supply chains are vulnerable to disruptions, leading to shortages of essential goods that can ripple across the globe.

The consolidation of corporate power in key sectors like agriculture creates dangerous monopolies that can manipulate markets, exploit farmers and ignore environmental safeguards with impunity.

The struggle against the intertwining of political centralisation and corporate consolidation is a battle for a future where power is distributed equitably, where local voices matter and where the interests of communities and the environment take precedence over corporate profits.

The stakes could not be higher. If we fail to check the runaway consolidation of political and corporate power, we risk sliding into a form of corporate feudalism or techno-feudalism, where the vast majority of people are reduced to serfs in service of a powerful elite.

Food and Agriculture

More specifically, the consolidation of corporate power in food and agriculture has far-reaching and deeply concerning implications for farmers, ordinary people and the environment. This concentration of control in the hands of a few transnational corporations has created a system that prioritises profit over ecological sustainability, health and food sovereignty.

For farmers, the consequences are dire. The consolidation of the agriculture industry has led to a dramatic reduction in the number of small farms. The shift towards large-scale industrial farming has not only pushed many small farmers out of business but also trapped those who remain in a cycle of dependency on a handful of corporations for seeds, chemicals and market access. This loss of autonomy leaves farmers vulnerable to exploitative practices and reduces their ability to make decisions based on local needs and conditions.

The impact on the wider population is equally troubling. While the illusion of choice persists in grocery stores, the reality is that a small number of corporations control the majority of food products. This concentration of power allows these companies to manipulate prices via aggressive discounting to destroy competition or to engage in profiteering through unnecessary price increases. Moreover, the focus on highly profitable, low-cost-ingredient processed foods high in fats, sugars and salt has contributed to a global health crisis, with rising rates of obesity and diet-related chronic diseases.

Environmentally, the consequences of this corporate-controlled system are catastrophic. The industrial agricultural model promoted by these large corporations relies heavily on chemical inputs, monoculture farming and practices that degrade soil health, waterways and biodiversity.

The centralisation of food production and distribution has also created a dangerously fragile system. As the COVID event demonstrated, disruptions in this highly consolidated supply chain can quickly lead to food shortages and price spikes. This lack of resilience poses a serious threat to global food security, particularly in times of crisis.

Perhaps most alarmingly, this consolidated system is eroding food sovereignty — the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems. As global corporations increasingly control what is grown and how it is distributed, local communities lose the ability to make decisions about their food systems.

The adverse implications of corporate consolidation in our food and agriculture system are profound and far-reaching. They threaten not only our current food security and public health but also the long-term sustainability of the planet’s food production capacity. Addressing this issue is not just about changing our food system; it’s about reclaiming democratic rights and ensuring a just and sustainable future for all.

In India, as will be shown, the trends outlined above have concerning implications. These trends, driven by neoliberal policies and the growing influence of transnational corporations, are reshaping the landscape of Indian agriculture in ways that threaten traditional farming practices, food security and rural livelihoods.

One of the most significant impacts is on small and marginal farmers, who make up about 85 per cent of India’s farming community (the importance of small farms will be discussed later). As corporate entities gain more control over various stages of the agricultural chain, these farmers face increasing pressure and vulnerability. They often find themselves at a disadvantage when negotiating prices or accessing markets, leading to reduced incomes and increased debt.

The consolidation of power in the hands of a few large corporations also poses a threat to India’s food sovereignty. As these companies gain control over seeds, inputs and distribution channels, we could see a further reduction in crop diversity and a shift towards monoculture (contract) farming.

This may also exacerbate the overuse of money-spinning proprietary chemical inputs, the degradation of soil and human health and the depletion of water resources, which are already major concerns in the country. The environmental costs of this approach are significant and could have long-lasting impacts on India’s agricultural productivity and food security.

Furthermore, the corporatisation of agriculture threatens to erode traditional farming knowledge and practices that have been developed over generations. These practices, often more suited to local ecological conditions and more sustainable in the long term, risk being lost as standardised, corporate-driven farming ends up commodifying knowledge and practices (this will become clear later).

The impact on rural communities extends beyond just the economic sphere. As the corporatisation of agriculture takes hold, there’s a risk of further rural-urban migration, as small farmers are pushed off their land. This can lead to the breakdown of rural social structures and exacerbate urban poverty and unemployment.

The influence of corporate interests on agricultural research and policy is also a matter of concern. When private sector funding becomes more dominant in agricultural research, there is a risk that research priorities become skewed towards corporate interests rather than the needs of small farmers or ecological sustainability.

Across the globe, an insidious corporatisation is reshaping agriculture. The consequences of this shift are far-reaching and deeply troubling, touching every aspect of the food system and, by extension, the very fabric of our societies.

These corporations tell us that such a process goes hand in hand with the modernisation of the sector. The narrative of the need to ‘modernise agriculture’ pushed by corporations like Bayer, Corteva and Syngenta is nothing more than a thinly veiled attempt to secure control of the agricultural sector and ensure corporate dependency.

Their vision of ‘development’ entails decision-making centralised in the hands of government and corporate entities, systematically weakening traditional local governance structures, and pushing top-down policies that favour large-scale industrial farming at the expense of small-scale, diversified agriculture.

Ultimately, the struggle against corporate consolidation in agriculture is not just about changing our food system. It’s about recognising that food is not just a commodity but a fundamental human right and a cornerstone of our cultures and communities.

There is a battle for the soul of our food system, for the future of our rural communities, for the health of our ecosystems and for the very nature of our societies. It’s a fight we cannot afford to lose. We must stand united to reclaim our food sovereignty and build a food system that nourishes not just our bodies but our communities.

A fundamental restructuring of our food and agriculture systems is required. This should include antitrust enforcement to break up corporate monopolies, policies that support small and medium-sized farms and investment in research for agroecological farming methods. We must also work to shorten supply chains, promoting local food systems and territorial markets that are more resilient and responsive to community needs.

The path ahead is challenging, but the alternative of a world where our food system is controlled by a handful of corporations, where biodiversity is decimated, where farmers are reduced to serfs on their own land and where our health is sacrificed for corporate profits is simply unacceptable.

Chapter II:

Sick to Death

The world is experiencing a micronutrient food and health crisis. Micronutrient deficiency now affects billions of people. Micronutrients are key vitamins and minerals and deficiencies can cause severe health conditions. They are important for various functions, including blood clotting, brain development, the immune system, energy production and bone health, and play a critical role in disease prevention.

The root of the crisis is due to an increased reliance on ultra processed foods (‘junk food’) and the way that modern food crops are grown in terms of the seeds used, the plants produced, the synthetic inputs required (fertilisers, pesticides etc.) and the effects on soil.

In 2007, nutritional therapist David Thomas noted a precipitous change in the USA towards convenience and pre-prepared foods often devoid of vital micronutrients yet packed with a cocktail of chemical additives, including colourings, flavourings and preservatives.

He noted that between 1940 and 2002 the character, growing methods, preparation, source and ultimate presentation of basic staples had changed significantly to the extent that trace elements and micronutrient contents have been severely depleted. Thomas added that ongoing research clearly demonstrates a significant relationship between deficiencies in micronutrients and physical and mental ill health.

Prior to the Green Revolution, many of the older crops that were displaced carried dramatically higher counts of nutrients per calorie. For instance, the iron content of millet is four times that of rice, and oats carry four times more zinc than wheat. As a result, between 1961 and 2011, the protein, zinc and iron contents of the world’s directly consumed cereals declined by 4 per cent, 5 per cent and 19 per cent, respectively.

The authors of a 2010 paper in the International Journal of Environmental and Rural Development state that cropping systems promoted by the Green Revolution have resulted in reduced food-crop diversity and decreased availability of micronutrients. They note that micronutrient malnutrition is causing increased rates of cancer, heart disease, stroke, diabetes and osteoporosis in many lower income nations. They add that soils are increasingly affected by micronutrient disorders.

In 2016, India’s Central Soil Water Conservation Research and Training Institute reported that the country was losing 5,334 million tonnes of soil every year due to soil erosion because of indiscreet and excessive use of fertilisers, insecticides and pesticides over the years. On average, 16.4 tonnes of fertile soil is lost every year per hectare. It concluded that the non-judicious use of synthetic fertilisers had led to the deterioration of soil fertility causing loss of micro and macronutrients leading to poor soils and low yields.

The high-input, chemical-intensive Green Revolution with its hybrid seeds and synthetic fertilisers and pesticides helped the drive towards greater monocropping and has resulted in less diverse diets and less nutritious foods. Its long-term impact has led to soil degradation and mineral imbalances, which, in turn, have adversely affected human health.

But micronutrient depletion is not just due to a displacement of nutrient-dense staples in the diet or unhealthy soils. Take wheat, for example. Rothamsted Research in the UK has evaluated the mineral concentration of archived wheat grain and soil samples from the Broadbalk Wheat Experiment. The experiment began in 1843, and the findings show significant decreasing trends in the concentrations of zinc, copper, iron and magnesium in wheat grain since the 1960s.

The researchers say that the concentrations of these four minerals remained stable between 1845 and the mid 1960s but have since decreased significantly by 20-30 per cent. This coincided with the introduction of Green Revolution semi-dwarf, high-yielding cultivars. They noted that the concentrations in soil used in the experiment have either increased or remained stable. So, in this case, soil is not the issue.

A 2021 paper that appeared in the journal of Environmental and Experimental Botany reported that the large increase in the proportion of the global population suffering from zinc and iron deficiency over the last four decades has occurred since the Green Revolution and the introduction of its cultivars.

Reflecting the findings of Rothamsted Research in the UK, a recent study led by Indian Council of Agricultural Research scientists found the grains eaten in India have lost food value. They conclude that many of today’s crops fail to absorb sufficient nutrients even when soil is healthy.

The January 2024 article Indians consuming rice and wheat low in food value, high in toxins on the Down to Earth website reported on a study that found that rice and wheat, which meet over 50 per cent of the daily energy requirements of people in India, have lost up to 45 per cent of their food value in the past 50 years or so.

The concentration of essential nutrients like zinc and iron has decreased by 33 per cent and 27 per cent in rice and by 30 per cent and 19 per cent in wheat, respectively. At the same time, the concentration of arsenic, a toxic element, in rice has increased by 1,493 per cent.

Down to Earth also cites research by the Indian Council of Medical Research that indicates a 25 per cent rise in non-communicable diseases among the Indian population from 1990 to 2016.

India is home to one-third of the two billion global population suffering from micronutrient deficiency. This is partly because modern-bred cultivars of rice and wheat are less efficient in sequestering zinc and iron, regardless of their abundance in soils. Plants have lost their capacity to take up nutrients from the soil.

Increasing prevalence of diabetes, childhood leukaemia, childhood obesity, cardiovascular disorders, infertility, osteoporosis and rheumatoid arthritis, mental illnesses and so on have all been shown to have some direct relationship to diet and specifically micronutrient deficiency.

The large increase in the proportion of the global population suffering from zinc and iron deficiency over the last four decades has coincided with the global expansion of high-yielding, input-responsive cereal cultivars released in the post-Green Revolution era.

Agriculture and policy analyst Devinder Sharma says that high yield is inversely proportionate to plant nutrition: the drop in nutrition levels is so much that the high-yielding new wheat varieties have seen a steep fall in copper content, an essential trace mineral, by as much as 80 per cent, and some nutritionists ascribe this to a rise in cholesterol-related incidences across the world.

India is self-sufficient in various staples, but many of these foodstuffs are high calorie-low nutrient and have led to the displacement of more nutritionally diverse cropping systems and more nutrient-dense crops.

The importance of agronomist William Albrecht should not be overlooked here and his work on healthy soils and healthy people. In his experiments, he found that cows fed on less nutrient-dense crops ate more while cows that ate nutrient-rich grass stopped eating once their nutritional intake was satisfied. This may be one reason why we see rising rates of obesity at a time of micronutrient food insecurity.

It is interesting that, given the above discussion on the Green Revolution’s adverse impacts on nutrition, the paper New Histories of the Green Revolution (2019) by Prof. Glenn Stone debunks the claim that the Green Revolution boosted productivity: it merely put more (nutrient-deficient) wheat into the Indian diet at the expense of other food crops. Stone argues that food productivity per capita showed no increase or even actually decreased.

.

.

With this in mind, the table below makes for interesting reading. The data is provided by the National Productivity Council India (an autonomous body of the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade, Ministry of Commerce and Industry).

As mentioned earlier with reference to Albrecht, obesity has become a concern worldwide, including in India. This problem is multi-dimensional and, as alluded to, excess calorific intake and nutrient-poor food is a factor, leading to the consumption of sugary, fat-laden ultra processed food in an attempt to fill the nutritional gap. But there is also considerable evidence linking human exposure to agrochemicals with obesity.

The September 2020 paper Agrochemicals and Obesity in the journal Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology summarises human epidemiological evidence and experimental animal studies supporting the association between agrochemical exposure and obesity and outlines possible mechanistic underpinnings for this link.

Numerous other studies have also noted that exposure to pesticides has been associated with obesity and diabetes. For example, a 2022 paper in the journal Endocrine reports that first contact with environmental pesticides occurs during critical phases of life, such as gestation and lactation, which can lead to damage in central and peripheral tissues, subsequently programming disorders early and later in life.

A 2013 paper in the journal Entropy on pathways to modern diseases reported that glyphosate (the active ingredient in Bayer-Monsanto’s Roundup), the most popular herbicide used worldwide, enhances the damaging effects of other food borne chemical residues and environmental toxins. The negative impact is insidious and manifests slowly over time as inflammation damages cellular systems throughout the body, resulting in conditions associated with a Western diet, which include gastrointestinal disorders, obesity, diabetes, heart disease, depression, autism, infertility, cancer and Alzheimer’s disease.

Despite these findings, campaigner Rosemary Mason has drawn attention to how official government and industry narratives try to divert attention from the role of glyphosate in obesity (and other conditions) by urging the public to exercise and cut down on “biscuits”.

In a January 2024 article, Kit Knightly, on the OffGuardian website, notes how big pharma is attempting to individualise obesity and make millions by pushing its ‘medical cures’ and drugs for the condition.

To deal with micronutrient deficiencies, other money-spinning initiatives for industry are being pushed, not least biofortification of foodstuffs and plants and genetic engineering.

Industry narratives have nothing to say about the food system itself in terms of food being regarded as just another commodity to be rinsed for profit regardless of the impacts on human health or the environment. We simply witness more techno-fix ‘solutions’ being rolled out to supposedly address the impacts of previous ‘innovations’ and policy decisions that benefitted the bottom line of Western agribusiness (and big pharma, which profits from the rising rates of disease and conditions).

Quick techno-fixes do not offer genuine solutions to the problems outlined above. Such solutions involve challenging corporate power that shapes narratives and policies to suit its agenda. Healthy food, healthy people and healthy societies are not created at some ever-sprawling life sciences park that specialises in manipulating food and the human body (for corporate gain) under the banner of ‘innovation’ and ‘health’ while leaving intact the power relations that underpin bad food and ill health.

A radical overhaul of the food system is required, from how food is grown to how society should be organised. This involves creating food sovereignty, encouraging localism, local markets and short supply chains, rejecting neoliberal globalisation, supporting smallholder agriculture and land reform while incentivising agroecological practices that build soil fertility, use and develop high-productive landraces and a focus on nutrition per acre rather than increased grain size, ‘yield’ and ‘output’.

That’s how you create healthy food, healthy people and healthy societies.

Chapter III

Commodification of Farmland

The relationship between financial investment and the commodification of farmland is increasingly significant for understanding the dynamics of modern agriculture and its implications for food systems. Financial institutions, including pension funds and investment firms, have turned farmland into a lucrative asset class, helping to fuel a paradigm shift in agricultural practices.

This financialisation of farmland not only affects the economic landscape, opening up fresh investment opportunities, but also perpetuates an industrial agricultural model that prioritises profit over sustainability, sound agricultural practices and public health.

The commodification of farmland involves transforming land into a tradable commodity, which is driven by the interests of big financial entities seeking high returns on their investments. This financial pressure leads to the aggregation of land into larger, industrial-scale farms owned by corporations or investment funds, which tend to employ input-intensive farming practices that degrade soil health and reduce biodiversity.

The influx of capital into farmland has further fuelled an industrial agricultural model characterised by monocultures, heavy reliance on chemical inputs and a focus on maximising yields at the expense of human health, ecological balance and a systems approach (more on this later).

The shift towards large-scale intensive farming operations has also diminished the role of smallholder farmers, who have traditionally played a major role in local food security and rural economies, thereby undermining community resilience and exacerbating food insecurity.

Financial Asset

Between 2008 and 2022, land prices nearly doubled throughout the world and tripled in Central-Eastern Europe. In the UK, an influx of investment from pension funds and private wealth contributed to a doubling of farmland prices from 2010-2015. Land prices in the US agricultural heartlands of Iowa quadrupled between 2002 and 2020.

.

A wheat field in Essex (Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

.

Agricultural investment funds rose ten-fold between 2005 and 2018 and now regularly include farmland as a stand-alone asset class, with US investors having doubled their stakes in farmland since 2020.

Meanwhile, agricultural commodity traders are speculating on farmland through their own private equity subsidiaries, while new financial derivatives are allowing speculators to accrue land parcels and lease them back to struggling farmers, driving steep and sustained land price inflation.

Moreover, top-down ‘green grabs’ now account for 20 per cent of large-scale land deals. Government pledges for land-based carbon removals alone add up to almost 1.2 billion hectares, equivalent to total global cropland. Carbon offset markets are expected to quadruple in the next seven years.

These are some of the findings published in the report ‘Land Squeeze’ (May 2024) by the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems (IPES), a non-profit thinktank headquartered in Brussels.

The report says that agricultural land is increasingly being turned into a financial asset at the expense of small- and medium-scale farming, leading to land price inflation. Furthermore, the COVID-19 event and the conflict in Ukraine helped promote the ‘feed the world’ panic narrative, prompting agribusiness and investors to secure land for export commodity production and urging governments to deregulate land markets and adopt pro-investor policies.

However, despite sky-rocketing food prices, there was, according to the IPES in 2022, sufficient food and no risk of global food supply shortages. The increased food prices were due to speculation on food commodities, corporate profiteering and a heavy reliance on food imports. But the self-serving narrative pushed by big agribusiness and land investors prevailed.

At the same time, carbon and biodiversity offset markets are facilitating massive land transactions, bringing major polluters into land markets. The IPES notes that Shell has set aside more than $450 million for carbon offsetting projects. Land is also being appropriated for biofuels and green energy production, including water-intensive ‘green hydrogen’ projects that pose risks to local food cultivation.

In addition, much-needed agricultural land is being repurposed for extractive industries and mega-developments. For example, urbanisation and mega-infrastructure developments in Asia and Africa are claiming prime farmland.

According to the IPES, between 2000 and 2030, up to 3.3 million hectares of the world’s farmland will have been swallowed up by expanding megacities. Some 80 per cent of land loss to urbanisation is occurring in Asia and Africa. In India, 1.5 million hectares are estimated to have been lost to urban growth between 1955 and1985, a further 800,000 hectares lost between 1985 and 2000, with steady ongoing losses to this day.

In a December 2016 paper on urban land expansion, it was projected that by 2030, globally, urban areas will have tripled in size, expanding into cropland. Around 60 per cent of the world’s cropland lies on the outskirts of cities, and this land is, on average, twice as productive as land elsewhere on the globe.

This means that, as cities expand, millions of small-scale farmers are being displaced. These farmers produce the majority of food in lower income countries and are key to global food security. In their place, as their land is concreted over, we are seeing the aggregation of remaining agricultural land into large-scale farms, land buy ups and further land investments and the spread of industrial agriculture and all it brings, including poor food and diets, illness, environmental devastation and the destruction of rural communities.

Investment funds have no real interest in farming or ensuring food security. They tend to invest for between only 10 and 15 years and can leave a trail of long-term environmental and social devastation and serve to undermine local and regional food security. Short- to medium-term returns on investments trump any notions of healthy food or human need.

The IPES notes that, globally, just 1 per cent of the world’s largest farms now control 70 per cent of the world’s farmland. These tend to be input-intensive, industrial-scale farms that are straining resources, rapidly degrading farmland and further squeezing out smallholders. Additionally, agribusiness giants are pursuing monopolistic practices that drive up costs for farmers. These dynamics are creating systematic economic precarity for farmers, effectively forcing them to ‘get big or get out’.

Factor in land degradation, much of which is attributable to modern chemical-intensive farming practices, and we have a recipe for global food insecurity.

In India, more than 70 per cent of its arable land is affected by one or more forms of land degradation.

Also consider that the Indian government has sanctioned 50 solar parks, covering one million hectares in seven states. More than 74 per cent of solar is on land of agricultural (67 per cent) or natural ecosystem value (7 per cent), causing potential food security and biodiversity conflicts. The IPES report notes that since 2017 there have been more than 15 instances of conflict in India linked with these projects.

What is the impact of all this on farming and what might the future hold?

Nettie Wiebe, from the IPES, explains:

“Imagine trying to start a farm when 70 per cent of farmland is already controlled by just 1 per cent of the largest farms — and when land prices have risen for 20 years in a row, like in North America. That’s the stark reality young farmers face today. Farmland is increasingly owned not by farmers but by speculators, pension funds and big agribusinesses looking to cash in. Land prices have skyrocketed so high it’s becoming impossible to make a living from farming. This is reaching a tipping point — small and medium scale farming is simply being squeezed out.”

Susan Chomba, also from the IPES, says that soaring land prices and land grabs are driving an unprecedented ‘land squeeze’, accelerating inequality and threatening food production. Moreover, the rush for dubious carbon projects, tree planting schemes, clean fuels and speculative buying is displacing not only small-scale farmers but also indigenous peoples.

Huge swathes of farmland are being acquired by governments and corporations for these ‘green grabs’, despite little evidence of climate benefits. This issue is particularly affecting Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa. The IPES notes that some 25 million hectares of land have been snapped up for carbon projects by a single ‘environmental asset creation’ firm, UAE-based ‘Blue Carbon’, through agreements with the governments of Kenya, Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Zambia and Liberia.

According to the IPES, the ‘land squeeze’ is leading to farmer revolts, rural exodus, rural poverty and food insecurity. With global farmland prices having doubled in 15 years, farmers, peasants, and indigenous peoples are losing their land (or forced to downsize), while young farmers face significant barriers in accessing land to farm.

The IPES calls for action to halt green grabs and remove speculative investment from land markets and establish integrated governance for land, environment and food systems to ensure a just transition. It also calls for support for collective ownership of farms and innovative financing for farmers to access land and wants a new deal for farmers and rural areas, and that includes a new generation of land and agrarian reforms.

Capitalist Imperative

Capital accumulation based on the financialisation of farmland accelerated after the 2008 financial crisis. However, financialisation of the economy in general goes back to the 1970s and 1980s when we witnessed a deceleration of economic growth based on industrial production. The response was to compensate via financial capitalism and financial intermediation.

Professor John Bellamy Foster, writing in 2010, not long after the 2008 crisis, stated:

“Lacking an outlet in production, capital took refuge in speculation in debt-leveraged finance (a bewildering array of options, futures, derivatives, swaps etc.).”

The neoliberal agenda was the political expression of capital’s response to the stagnation and included the raiding and sacking of public budgets, the expansion of credit to consumers and governments to sustain spending and consumption and frenzied financial speculation.

With the engine of capital accumulation via production no longer firing on all cylinders, the emergency backup of financial expansion took over. We have seen a shift from real capital formation in many Western economies, which increases overall economic output, towards the appreciation of financial assets, which increases wealth claims but not output.

Farmland is being transformed from a resource supporting food production and rural stability to a financial asset and speculative commodity. An asset class where wealthy investors can park their capital to further profit from inflated asset prices.

The net-zero green agenda also has to be seen in this context: when capital struggles to make sufficient profit, productive wealth (capital) over accumulates and depreciates; to avoid crisis, constant growth and, in this case, the creation of fresh ‘green’ investment opportunities is required.

The IPES report notes that nearly 45 per cent of all farmland investments in 2018, worth roughly $15 billion, came from pension funds and insurance companies. Based on workers’ contributions, pension fund investments in farmland are promoting land speculation, industrial agriculture and the interests of big agribusiness at the expense of smallholder farmers. Workers’ futures are tied to pension funds, which are supporting the growth and power of global finance and the degradation of other workers (in this case, cultivators).

Sofía Monsalve Suárez, from the IPES, states:

“It’s time decision-makers stop shirking their responsibility and start to tackle rural decline. The financialisation and liberalisation of land markets is ruining livelihoods and threatening the right to food. Instead of opening the floodgates to speculative capital, governments need to take concrete steps to halt bogus ‘green grabs’ and invest in rural development, sustainable farming and community-led conservation.”

With pensions tied to an increasingly commodified food system, ordinary people have become deeply incorporated into a capitalist economy that requires private profit at the expense of public well-being. The links between big finance, the food system, illness and big pharma were described in Sickening Profits: The Global Food System’s Poisoned Food and Toxic Wealth.

That book highlighted a cyclical relationship where financial institutions like BlackRock benefit from both their investments in the global food system and their investments in pharmaceuticals. At the same time, the relationship between ordinary people’s pensions and investments and the commodification of farmland further illustrates a complex interplay between finance and agriculture.

Addressing these challenges requires a critical examination of how financial interests shape agricultural practices and a concerted effort towards more sustainable food systems that prioritise ecological integrity and community well-being over mere profitability.

Systems Approach

Earlier in this chapter, it was stated that the influx of capital into farmland has further fuelled an industrial agricultural model characterised by monocultures, heavy reliance on chemical inputs and a focus on maximising yields at the expense of ecological balance and a systems approach. But what is a systems approach?

It involves understanding agriculture as part of a broader ecological and social system. It acknowledges that agricultural practices affect and are affected by environmental health, community well-being and economic viability.

However, industrial agriculture often overlooks these interconnections, leading to detrimental outcomes such as soil degradation, polluted waterways, loss of biodiversity, the destruction of rural communities, small-scale farms and local economies and negative health impacts. By contrast, a systems approach promotes agroecological principles that prioritise local food security, sustainable practices and the resilience of farming communities.

Agroecology serves as a primary framework within this systems approach. It integrates scientific research with traditional knowledge and grassroots participation, fostering practices that enhance ecological balance while ensuring farmers’ livelihoods. This method encourages diverse cropping systems, natural pest management and sustainable resource use, which collectively contribute to more resilient agricultural ecosystems. Agroecology not only addresses immediate agricultural challenges but also engages with broader political and economic issues affecting food systems.

Moreover, a systems approach prioritises diverse nutrition production per acre, which contrasts sharply with conventional, reductionist agricultural models that focus predominantly on maximising yields of a single crop. Agroecological methods, which are foundational to this systems perspective, can lead to improved nutritional outcomes: by cultivating a wider variety of crops, farmers can enhance the nutritional quality of food produced on each acre, thereby addressing issues of malnutrition and food insecurity more effectively.

Localised food systems and the primacy of small farms are critical to a systems approach. By reducing dependency on global supply chains dominated by big finance and large agribusiness, localised systems can enhance food sovereignty and empower communities.

This shift not only mitigates vulnerability to global market fluctuations and supply chain crises but also fosters self-sufficiency and resilience against environmental changes. A systems approach thus advocates for policies that support smallholder farmers and promote sustainable practices tailored to local conditions. (For further insight into agroecology and its feasibility, successes and scaling up, there is an entire chapter on agroecology in Food, Dependency and Dispossession: Resisting the New World Order.)

Chapter IV

Digital Panopticon and the Future of Food

Throughout the world, from the Netherlands to India, farmers are protesting. The protests might appear to have little in common. But they do. Farmers are increasingly finding it difficult to make a living, whether, for instance, because of neoliberal trade policies that lead to the import of produce that undermines domestic production and undercuts prices, the withdrawal of state support or the implementation of net-zero emissions policies that set unrealistic targets.

The common thread is that, by one way or another, farming is deliberately being made impossible or financially non-viable. The aim is to drive most farmers off the land and ram through an agenda that by its very nature seems likely to produce shortages and undermine food security.

.

Farmers’ protest in The Hague 1 October 2019. (Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0)

.

A ‘one world agriculture’ global agenda is being promoted by the likes of the Gates Foundation and the World Economic Forum. It involves a vision of food and farming that sees companies such as Bayer, Corteva, Syngenta and Cargill working with Microsoft, Google and the big-tech giants to facilitate AI-driven farmerless farms, laboratory-engineered ‘food’ and retail dominated by the likes of Amazon and Walmart. A cartel of data owners, proprietary input suppliers and e-commerce platforms at the commanding heights of the economy.

The agenda is the brainchild of a digital-corporate-financial complex that wants to transform and control all aspects of life and human behaviour. This complex forms part of an authoritarian global elite that has the ability to coordinate its agenda globally via the United Nations, the World Economic Forum, the World Trade Organization (WTO), the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund and other supranational organisations, including influential think tanks and foundations (Gates, Rockefeller etc.).

Its agenda for food and farming is euphemistically called a ‘food transition’. Big agribusiness and ‘philanthropic’ foundations position themselves as the saviours of humanity due to their much-promoted plans to ‘feed the world’ with high-tech ‘precision’ farming’, ‘data-driven’ agriculture and ‘green’ (net-zero) production — with a warped notion of ‘sustainability’ being the mantra.

A much talked about ‘food transition’ goes hand in hand with an energy transition, net-zero ideology, programmable central bank digital currencies, the censorship of free speech and clampdowns on protest.

Economic Crisis

To properly understand these processes, we need to first locate what is essentially a social and economic reset within the context of a collapsing financial system.

Writer Ted Reece notes that the general rate of profit has trended downwards from an estimated 43 per cent in the 1870s to 17 per cent in the 2000s. By late 2019, many companies could not generate enough profit. Falling turnover, squeezed margins, limited cashflows and highly leveraged balance sheets were prevalent.

Professor Fabio Vighi of Cardiff University has described how closing down the global economy in early 2020 under the guise of fighting a supposedly new and novel pathogen allowed the US Federal Reserve to flood collapsing financial markets (COVID relief) with freshly printed money without causing hyperinflation. Lockdowns curtailed economic activity, thereby removing demand for the newly printed money (credit) in the physical economy and preventing ‘contagion’.

According to investigative journalist Michael Byrant, €1.5 trillion was needed to deal with the crisis in Europe alone. The financial collapse staring European central bankers in the face came to a head in 2019. The appearance of a ‘novel virus’ provided a convenient cover story.

The European Central Bank agreed to a €1.31 trillion bailout of banks followed by the EU agreeing to a €750 billion recovery fund for European states and corporations. This package of long-term, ultra-cheap credit to hundreds of banks was sold to the public as a necessary programme to cushion the impact of the ‘pandemic’ on businesses and workers.

In response to a collapsing neoliberalism, we are now seeing the rollout of an authoritarian great reset — an agenda that intends to reshape the economy and change how we live.

Shift to Authoritarianism

The new economy is to be dominated by a handful of tech giants, global conglomerates and e-commerce platforms, and new markets will also be created through the financialisation of nature, which is to be colonised, commodified and traded under the notion of protecting the environment.

In recent years, we have witnessed an overaccumulation of capital, and the creation of such markets will provide fresh investment opportunities (including dodgy carbon offsetting Ponzi schemes) for the super-rich to park their wealth and prosper.

This great reset envisages a transformation of Western societies, resulting in permanent restrictions on fundamental liberties and mass surveillance. Being rolled out under the benign term of a ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’, the World Economic Forum (WEF) says the public will eventually ‘rent’ everything they require (remember the WEF video ‘you will own nothing and be happy’?): stripping the right of ownership under the guise of a ‘green economy’ and underpinned by the rhetoric of ‘sustainable consumption’ and ‘climate emergency’.

.

Klaus Schwab, Bill Gates – World Economic Forum Annual Meeting Davos 2008 (Copyright World Economic Forum by Remy Steinegger)

.

Climate alarmism and the mantra of sustainability are about promoting money-making schemes.

But they also serve another purpose: social control.

Neoliberalism has run its course, resulting in the impoverishment of large sections of the population. But to dampen dissent and lower expectations, the levels of personal freedom we have been used to will not be tolerated. This means that the wider population will be subjected to the discipline of an emerging surveillance state.

To push back against any dissent, ordinary people are being told that they must sacrifice personal liberty in order to protect public health, societal security (those terrible Russians, Islamic extremists or that Sunak-designated bogeyman George Galloway) or the climate; in the case of the climate, this means, for instance, travelling less and eating synthetic ‘meat’.

Unlike in the old normal of neoliberalism, an ideological shift is occurring whereby personal freedoms are increasingly depicted as being dangerous because they run counter to the collective good.

A main reason for this ideological shift is to ensure that the masses get used to lower living standards and accept them. Consider, for instance, the Bank of England’s chief economist Huw Pill saying that people should ‘accept’ being poorer. And then there is Rob Kapito of the world’s biggest asset management firm BlackRock, who says that a “very entitled” generation must deal with scarcity for the first time in their lives.

At the same time, to muddy the waters, the message is that lower living standards are the result of the conflict in Ukraine and supply shocks that both the war and ‘the virus’ have caused.

The net-zero carbon emissions agenda will help legitimise lower living standards (reducing your carbon footprint) while reinforcing the notion that our rights must be sacrificed for the greater good. You will own nothing, not because the rich and their neoliberal agenda made you poor but because you will be instructed to stop being irresponsible and must act to protect the planet.

Net-zero Agenda

But what of this shift towards net-zero greenhouse gas emissions and the plan to slash our carbon footprints? Is it even feasible or necessary?

Gordon Hughes, a former World Bank economist and current professor of economics at the University of Edinburgh, says in a 2024 report that current UK and European net-zero policies will likely lead to further economic ruin.

Apparently, the only viable way to raise the cash for sufficient new capital expenditure (on wind and solar infrastructure) would be a two decades-long reduction in private consumption of up to 10 per cent. Such a shock has never occurred in the last century outside war; even then, never for more than a decade.

But this agenda will also cause serious environmental degradation. So says Andrew Nikiforuk in the article The Rising Chorus of Renewable Energy Skeptics, which outlines how the green techno-dream is vastly destructive.

He lists the devastating environmental impacts of an even more mineral-intensive system based on renewables and warns:

“The whole process of replacing a declining system with a more complex mining-based enterprise is now supposed to take place with a fragile banking system, dysfunctional democracies, broken supply chains, critical mineral shortages and hostile geopolitics.”

All of this assumes that global warming is real and anthropogenic. Not everyone agrees. In the article Global warming and the confrontation between the West and the rest of the world, journalist Thierry Meyssan argues that net zero is based on political ideology rather than science. But to state such things has become heresy in the Western countries and shouted down with accusations of ‘climate science denial’.

Regardless of such concerns, the march towards net zero continues, and key to this is the United Nations Agenda 2030 for Sustainable Development Goals.

.

A proposal to visualize the 17 SDGs in a thematic pyramid (Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0)

.

Today, almost every business or corporate report, website or brochure includes a multitude of references to ‘carbon footprints’, ‘sustainability’, ‘net zero’ or ‘climate neutrality’ and how a company or organisation intends to achieve its sustainability targets. Green profiling, green bonds and green investments go hand in hand with displaying ‘green’ credentials and ambitions wherever and whenever possible.

It seems anyone and everyone in business is planting their corporate flag on the summit of sustainability. Take Sainsbury’s, for instance. It is one of the ‘big six’ food retail supermarkets in the UK and has a vision for the future of food that it published in 2019 that dovetails with the so-called food transition and the interrelated net-zero agenda — you must change your eating habits and eat synthetic food to save the planet!

Here’s a quote from it:

“Personalised Optimisation is a trend that could see people chipped and connected like never before. A significant step on from wearable tech used today, the advent of personal microchips and neural laces has the potential to see all of our genetic, health and situational data recorded, stored and analysed by algorithms which could work out exactly what we need to support us at a particular time in our life. Retailers, such as Sainsbury’s could play a critical role to support this, arranging delivery of the needed food within thirty minutes — perhaps by drone.”

Tracked, traced and chipped — for your own benefit. Corporations accessing all of our personal data, right down to our DNA. The report is littered with references to sustainability and the climate or environment, and it is difficult not to get the impression that it is written so as to leave the reader awestruck by the technological possibilities. We shall return to this report in the next chapter.

The report appears to be part of a paradigm that promotes a brave new world of technological innovation but has nothing to say about power — who determines policies that have led to massive inequalities, poverty, malnutrition, food insecurity and hunger and who is responsible for the degradation of the environment in the first place — is nothing new.

The essence of power is conveniently glossed over, not least because those involved in the prevailing food regime are also shaping the techno-utopian fairytale where everyone lives happily ever after eating synthetic food while living in a digital panopticon.

Fake Green

The type of ‘green’ agenda being pushed is not just about social engineering and behavioural change; it is also a multi-trillion market opportunity for lining the pockets of rich investors and subsidy-sucking green infrastructure firms.

It is, furthermore, a type of green that plans to cover much of the countryside with wind farms and solar panels with most farmers no longer farming. A recipe for food insecurity.

Those investing in the ‘green’ agenda care first and foremost about profit. The supremely influential BlackRock is not only promoting this agenda; it also invests in the current food system and the corporations responsible for polluted waterways, degraded soils, the displacement of smallholder farmers, a spiralling public health crisis, malnutrition and much more.

It also invests in healthcare — an industry that thrives on the illnesses and conditions created by eating the substandard food that the current system produces.

Did Larry Fink, the top man at BlackRock, suddenly develop a conscience and become an environmentalist who cares about the planet and ordinary people? Of course not. He smells ever more profit in ‘climate-friendly’, ‘precision’ agriculture, genetic engineering and facilitating a new technocratic fake-green normal.

Any serious deliberations on the future of food would surely consider issues like food sovereignty, the role of agroecology and the strengthening of family farms — the backbone of current global food production.

The aforementioned article by Andrew Nikiforuk concludes that, if we are really serious about our impacts on the environment, we must scale back our needs and simplify society.

In terms of food, the solution rests on a low-input approach that strengthens rural communities and local markets and prioritises smallholder farms and small independent enterprises and retailers, localised democratic food systems and a concept of food sovereignty based on self-sufficiency, agroecological principles and regenerative agriculture.

It would involve facilitating the right to culturally appropriate food that is nutritionally dense due to diverse cropping patterns and free from toxic chemicals while ensuring local ownership and stewardship of common resources like land, water, soil and seeds.

That’s where genuine environmentalism, ‘sustainability’, social justice and the future of food begins. But there’s no profit or role in that for Fink or the big agribusiness and tech giants that despise such approaches.

Chapter V

Manifesto for Corporate Control and Technocratic Tyranny

Sainsbury’s Future of Food report (2019), mentioned in the previous chapter, is not merely a misguided attempt at forecasting future trends and habits; it reads more like a manifesto for corporate control and technocratic tyranny disguised as ‘progress’. This document epitomises everything wrong with the industrial food system’s vision for our future. It represents a dystopian roadmap to a world where our most fundamental connection to nature and culture — our food — is hijacked by corporate interests and mediated through a maze of unnecessary and potentially harmful technologies.

.

Illustration by Margarita Mitrovic / Screenshot from Sainsbury’s Report

.

The wild predictions and technological ‘solutions’ presented in the report reveal a profound disconnection from the lived experiences of ordinary people and the real challenges facing our food systems. Its claim (in 2019) that a quarter of Britons will be vegetarian by 2025 seems way off the mark. But it fits a narrative that seeks to reshape our diets and food culture. Once you convince the reader that things are going to be a certain way in the future, it is easier to pave the way for normalising what appears elsewhere in the report: lab-grown meat, 3D-printed foods and space farming.

Of course, the underlying assumption is that giant corporations — and supermarkets like Sainsbury’s — will be controlling everything and rolling out marvellous ‘innovations’ under the guise of ‘feeding the world’ or ‘saving the planet’. There is no concern expressed in the report about the consolidation of corporate-technocratic control over the food system.

By promoting high-tech solutions, the report seemingly advocates for a future where our food supply is entirely dependent on complex technologies controlled by a handful of corporations.

The report talks of ‘artisan factories’ run by robots. Is this meant to get ordinary people to buy into Sainsbury’s vision of the future? Possibly, if the intention is to further alienate people from their food sources, making them ever more dependent on corporate-controlled, ultra-processed products.

It’s a future where the art of cooking, the joy of growing food and the cultural significance of traditional dishes are replaced by sterile, automated processes devoid of human touch and cultural meaning. This erosion of food culture and skills is not an unintended consequence — it’s a core feature of the corporate food system’s strategy to create a captive market of consumers unable to feed themselves without corporate intervention.

The report’s enthusiasm for personalised nutrition driven by AI and biometric data is akin to an Orwellian scenario that would give corporations unprecedented control over our dietary choices, turning the most fundamental human need into a data-mined, algorithm-driven commodity.

The privacy implications are staggering, as is the potential for new forms of discrimination and social control based on eating habits. Imagine a world where your insurance premiums are tied to your adherence to a corporate-prescribed diet or where your employment prospects are influenced by your ‘Food ID’. The possible dystopian reality lurking behind Sainsbury’s glossy predictions.

The report’s fixation on exotic ingredients like jellyfish and lichen draws attention away from the real issues affecting our food systems — corporate concentration, environmental degradation and the systematic destruction of local food cultures and economies. It would be better to address the root causes of food insecurity and malnutrition, which are fundamentally issues of poverty and inequality, not a lack of novel food sources.

Nothing is mentioned about the vital role of agroecology, traditional farming knowledge and food sovereignty in creating truly sustainable and just food systems. Instead, what we see is a future where every aspect of our diet is mediated by technology and corporate interests, from gene-edited crops to synthetic biology-derived foods. A direct assault on the principles of food sovereignty, which assert the right of peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods.

The report’s emphasis on lab-grown meat and other high-tech protein sources is particularly troubling. These technologies, far from being the environmental saviours they are promoted as, risk increasing energy use and further centralising food production in the hands of a few tech giants.

The massive energy requirements for large-scale cultured meat production are conveniently glossed over, as are the potential health risks of consuming these novel foods without long-term safety studies. This push for synthetic foods is not about sustainability or animal welfare — it’s about creating new, patentable food sources that can be controlled and monetised by corporations.

Moreover, the push for synthetic foods and ‘precision fermentation’ threatens to destroy the livelihoods of millions of small farmers and pastoralists worldwide, replacing them with a handful of high-tech facilities controlled by multinational corporations.

Is this meant to be ‘progress’?

It’s more like a boardroom recipe for increased food insecurity, rural poverty and corporate monopolisation. The destruction of traditional farming communities and practices would not only be an economic disaster but a cultural catastrophe, erasing millennia of accumulated knowledge and wisdom about sustainable food production.

The report’s casual mention of ‘sin taxes’ on meat signals a future where our dietary choices are increasingly policed and penalised by the state, likely at the behest of corporate interests.

The Issue of Meat

However, on the issue of the need to reduce meat consumption and replace meat with laboratory-manufactured items in order to reduce carbon emissions, it must be stated that the dramatic increase in the amount of meat consumed post-1945 was not necessarily the result of consumer preference; it had more to do with political policy, the mechanisation of agriculture and Green Revolution practices.

That much was made clear by Laila Kassam, who, in her 2017 article What’s grain got to do with it? How the problem of surplus grain was solved by increasing ‘meat’ consumption in post-WWII US, asked:

“Have you ever wondered how ‘meat’ became such a central part of the Western diet? Or how the industrialisation of ‘animal agriculture’ came about? It might seem like the natural outcome of the ‘free market’ meeting demand for more ‘meat’. But from what I have learned from Nibert (2002) and Winders and Nibert (2004), the story of how ‘meat’ consumption increased so much in the post-World War II period is anything but natural. They argue it is largely due to a decision in the 1940s by the US government to deal with the problem of surplus grain by increasing the production of ‘meat’.”

Kassam notes:

“In the second half of the 20th century, global ‘meat’ production increased by nearly 5 times. The amount of ‘meat’ eaten per person doubled. By 2050 ‘meat’ consumption is estimated to increase by 160 percent (The World Counts, 2017). While global per capita ‘meat’ consumption is currently 43 kg/year, it is nearly double in the UK (82 kg/year) and almost triple in the US (118 kg/year).”

Kassam notes that habits and desires are manipulated by elite groups for their own interests. Propaganda, advertising and ‘public relations’ are used to manufacture demand for products. Agribusiness corporations and the state have used these techniques to encourage ‘meat’ consumption, leading to the slaughter and untold misery of billions of creatures, as Kassam makes clear.

People were manipulated to buy into ‘meat culture’. Now they are being manipulated to buy out, again by elite groups. But ‘sin taxes’ and Orwellian-type controls on individual behaviour are not the way to go about reducing meat consumption.

So, what is the answer?

Kassam says that one way to do this is to support grassroots organisations and movements which are working to resist the power of global agribusiness and reclaim our food systems. Movements for food justice and food sovereignty which promote sustainable, agroecological production systems.

At least then people will be free from corporate manipulation and better placed to make their own food choices.

As Kassam says:

“From what I have learned so far, our oppression of other animals is not just a result of individual choices. It is underpinned by a state supported economic system driven by profit.”

Misplaced Priorities

Meanwhile, Sainsbury’s vision of food production in space and on other planets is perhaps the most egregious example of misplaced priorities. While around a billion struggle with hunger and malnutrition and many more with micronutrient deficiencies, corporate futurists are fantasising about growing food on Mars.

Is this supposed to be visionary thinking?

It’s a perfect encapsulation of the technocratic mindset that believes every problem can be solved with more technology, no matter how impractical or divorced from reality.

Moreover, by promoting a future dependent on complex, centralised technologies, we become increasingly vulnerable to system failures and corporate monopolies. A truly resilient food system should be decentralised, diverse and rooted in local knowledge and resources.

The report’s emphasis on nutrient delivery through implants, patches and intravenous methods is particularly disturbing. This represents the ultimate commodification of nutrition, reducing food to mere fuel and stripping away all cultural, social and sensory aspects of eating. It’s a vision that treats the human body as a machine to be optimised, rather than a living being with complex needs and experiences.

The idea of ‘grow-your-own’ ingredients for cultured meat and other synthetic foods at home is another example of how this technocratic vision co-opts and perverts concepts of self-sufficiency and local food production. Instead of encouraging people to grow real, whole foods, it proposes a dystopian parody of home food production that still keeps consumers dependent on corporate-supplied technologies and inputs. A clever marketing ploy to make synthetic foods seem more natural and acceptable.

The report’s predictions about AI-driven personal nutrition advisors and highly customised diets based on individual ‘Food IDs’ raise serious privacy concerns and threaten to further medicalise our relationship with food. While personalised nutrition could offer some benefits, the level of data collection and analysis required for such systems could lead to unprecedented corporate control over our dietary choices.

Furthermore, the emphasis on ‘artisan’ factories run by robots completely misunderstands the nature of artisanal food production. True artisanal foods are the product of human skill, creativity and cultural knowledge passed down through generations. It’s a perfect example of how the technocratic mindset reduces everything to mere processes that can be automated, ignoring the human and cultural elements that give food its true value.

The report’s vision of meat ‘assembled’ on 3D printing belts is another disturbing example of the ultra-processed future being proposed. This approach to food production treats nutrition as a mere assembly of nutrients, ignoring the complex interactions between whole foods and the human body. It’s a continuation of the reductionist thinking that has led to the current epidemic of diet-related diseases.

Sainsbury’s is essentially advocating for a future where our diets are even further removed from natural, whole foods.

The concept of ‘farms’ cultivating plants to make growth serum for cells is yet another step towards the complete artificialisation of the food supply. This approach further distances food production from natural processes. It’s a vision of farming that has more in common with pharmaceutical production than traditional agriculture, and it threatens to complete the transformation of food from a natural resource into an industrial product.

Sainsbury’s apparent enthusiasm for gene-edited and synthetic biology-derived foods is also concerning. These technologies’ rapid adoption without thorough long-term safety studies and public debate could lead to unforeseen health and environmental impacts. The history of agricultural biotechnology is rife with examples of unintended consequences, from the development of herbicide-resistant superweeds to the contamination of non-GM crops.

Is Sainsbury’s uncritically promoting these technologies, disregarding the precautionary principle?

Issues like food insecurity, malnutrition and environmental degradation are not primarily technical problems — they are the result of inequitable distribution of resources, exploitative economic systems and misguided policies. By framing these issues as purely technological challenges, Sainsbury’s is diverting attention from the need for systemic change and social justice in the food system.

The high-tech solutions proposed are likely to be accessible only to the wealthy, at least initially, creating a two-tiered food system where the rich have access to ‘optimized’ nutrition while the poor are left with increasingly degraded and processed options.

But the report’s apparent disregard for the cultural and social aspects of food is perhaps its most fundamental flaw. Food is not merely fuel for our bodies; it’s a central part of our cultural identities, social relationships and connection to the natural world. By reducing food to a series of nutrients to be optimised and delivered in the most efficient manner possible, Sainsbury’s is proposing a future that is not only less healthy but less human.

While Sainsbury’s Future of Food report can be regarded as a roadmap to a better future, it is really a corporate wish list, representing a dangerous consolidation of power in the hands of agribusiness giants and tech companies at the expense of farmers, consumers and the environment.

The report is symptomatic of a wider ideology that seeks to legitimise total corporate control over our food supply. And the result? A homogenised, tech-driven dystopia.

A technocratic nightmare that gives no regard for implementing food systems that are truly democratic, ecologically sound and rooted in the needs and knowledge of local communities.

The real future of food lies not in corporate labs and AI algorithms, but in the fields of agroecological farmers, the kitchens of home cooks and the markets of local food producers.

The path forward is not through more technology and corporate control but through a return to the principles of agroecology, food sovereignty and cultural diversity.

Chapter VI

From Agrarianism to Transhumanism: Long March to Dystopia

“A total demolition of the previous forms of existence is underway: how one comes into the world, biological sex, education, relationships, the family, even the diet that is about to become synthetic.” — Silvia Guerini, radical ecologist, in From the ‘Neutral’ Body to the Posthuman Cyborg (2023)

We are currently seeing an acceleration of the corporate consolidation of the entire global agri-food chain. The big data conglomerates, including Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook and Google, have joined traditional agribusiness giants, such as Corteva, Bayer, Cargill and Syngenta, in a quest to impose their model of food and agriculture on the world.

The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and big financial institutions, like BlackRock and Vanguard, are also involved, whether through buying up huge tracts of farmland, pushing biosynthetic (fake) food and genetic engineering technologies or more generally facilitating and financing the aims of the mega agri-food corporations.

The billionaire interests behind this try to portray their techno-solutionism as some kind of humanitarian endeavour: saving the planet with ‘climate-friendly solutions’, ‘helping farmers’ or ‘feeding the world’. But what it really amounts to is repackaging and greenwashing the dispossessive strategies of imperialism.