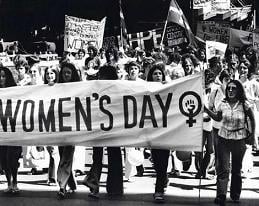

100 Years Ago: Women’s Day (1910-2010)

Socialist Women Declare a Global Feminist Holiday

Women are a revolutionary force. That fact shows in their holiday, International Women’s Day (IWD), both its past and present. Because the profit system depends on the second-class status of women, the day that honors them is bound to be connected to momentous happenings.

There were at least 984 events last year in 64 countries. The day is an official holiday in 29 countries — not accidentally, mostly those with an anti-capitalist history. They include China, Cuba, Vietnam, states in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, and some in Africa.

The wealthier nations — North American and European countries, Australia — don’t recognize it. It’s notable that both IWD and May Day, the international workers’ holiday, were started to commemorate the struggles of workers in the U.S. — but neither is recognized officially in the heart of Capital.

A militant beginning. The holiday’s roots are in the struggles of working women and their socialist supporters. It’s believed that a mass protest by women garment and textile workers in New York City in 1857 occurred on March 8, and that in March two years later the same women won a drive to unionize. They were fighting against brutal working conditions, low wages, and the 12-hour day.

On March 8, 1908, socialist women organized a demonstration of 15,000 in New York. Their demands were pay raises, shorter hours, the vote, and an end to child labor. After that, the Socialist Party of America decided to celebrate a women’s day in the U.S., the first of which was held in 1909.

International Women’s Day was founded the following year, a century ago, at the Second International Socialist Women’s Conference held alongside the International Socialist Congress in Copenhagen, Denmark. The attendees represented socialist parties, working women’s clubs, and unions, and included the first three women elected to the Finnish parliament, at a time when few women had the right to vote.

U.S. delegates went intending to propose an international women’s day, only to find that German feminist Clara Zetkin had beaten them to it. Zetkin was a prominent member of the German socialist party, which had a strong history of defending women’s rights. Women from 17 countries voted unanimously to create the holiday. The next year, 1911, celebrations started with a bang, with more than a million people demonstrating in Germany, Austria, Denmark and Switzerland.

The need for such a day got a chilling but powerful push from the great Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of March 25, 1911, in New York. Locked exits and poor safety measures caused the deaths of 146 workers, mostly women. It became an international scandal that ignited labor organizing. It helped build the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, which was one of the first primarily female unions and became one of the largest unions in the U.S.

In 1913 and 1914, as the drumbeats for World War I were beginning to sound, major IWD demonstrations calling for peace took place in Europe. World War I began in August 1914. For several years, IWD was suppressed both by capitalist governments and by some socialist parties, those that had betrayed international working-class solidarity by backing their own nations in the war.

A revolutionary spark. But the most momentous IWD so far was in Russia on March 8, 1917. The story is told magnificently in Leon Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution. Women started the insurrection that overthrew the all-powerful czar — and led to the Bolshevik revolution eight months later.

Women textile workers in Petersburg were desperate and angry because of severe food shortages and the slaughter of several million Russian soldiers in the war. They went on strike, and called on other factories to support them. The strike and demonstrations grew from day to day, and five days later, the Russian monarchy was gone for good.

Ongoing insurgency. IWD isn’t just a ceremonial occasion. In Iran in 2007, police violently broke up an IWD protest and arrested dozens of women. The day has a militant history in Iran.

On IWD in 1979, in the midst of the revolution that ousted the U.S.-backed shah, and just after the right-wing Islamic regime of Ayatollah Khomeini came to power, 100,000 women and male supporters rallied at Tehran University. Then 20,000 women, wearing western clothes instead of the mandated full-length veil, marched through the city. Protests were organized in other cities, too. Women demanded equal rights, including the right to dress as they wished. Religious vigilantes dispersed the women, although they fought back over the course of several days. It was the failure of left parties to defend the women that led to the ultimate defeat of the revolution.

Female leadership is a high-water mark in struggles too numerous to count. Women workers were instrumental in nationalizing banks during the uncompleted Portuguese revolution in 1977. Women played a vital role in Latin American upheavals of the 1980s, including Nicaragua’s Sandinista rebellion. Europe in the ’80s saw a huge upsurge of feminism, particularly within socialist and communist parties.

Last year, women played a forefront role in the uprising in Honduras against the coup that ousted the democratically elected president, Manuel Zelaya.

In the U.S., the huge feminist movement launched in the late 1960s began with radical aims. Despite the achievement of some reforms and a sea change in social attitudes, those aims remain to be fulfilled — as they do in the rest of the world.

The dynamism and revolutionary role of women workers that IWD commemorates is a key to understanding our times. Revolts by those on the bottom against the crimes of the profit system spring up continually. And those on the bottom are women, of all colors and nationalities and sexual persuasions, and as the most downtrodden part of every other oppressed group.

In the process of accomplishing their own liberation, women will be essential to the liberation of humanity.