When the CIA’s Empire Struck Back

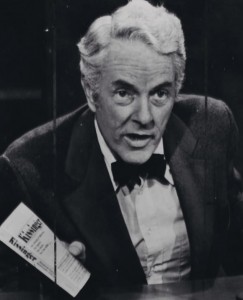

Photo: Rep. Otis Pike, D-New York.

In the mid-1970s, Rep. Otis Pike led a brave inquiry to rein in the excesses of the national security state. But the CIA and its defenders accused Pike of recklessness and vowed retaliation, assigning him to a political obscurity that continued to his recent death.

Otis Pike, who headed the House of Representatives’ only wide-ranging and in-depth investigation into intelligence agency abuses in the 1970s, died on Jan. 20. A man who should have received a hero’s farewell passed with barely a mention. To explain the significance of what he did, however, requires a solid bit of back story.

Until 1961, U.S. intelligence agencies operated almost entirely outside the view of the mainstream media and with very limited exposure to members of Congress. But then, the CIA had its first big public failure in the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba.

CIA Director Allen Dulles lured an inexperienced President John F. Kennedy into implementing a plan hatched under President Dwight Eisenhower. In Dulles’s scheme, the lightly armed invasion by Cuban exiles at the Bay of Pigs was almost surely doomed to fail, but he thought Kennedy would then have no choice but to send in a larger military force to overthrow Fidel Castro’s government. However, Kennedy refused to commit U.S. troops and later fired Dulles.

Despite that embarrassment, Dulles and other CIA veterans continued to wield extraordinary influence inside Official Washington. For instance, after Kennedy’s assassination on Nov. 22, 1963, Dulles became a key member of the Warren Commission investigating Kennedy’s murder. Though the inquiry was named after U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren, it should have been called the Dulles Commission because Dulles spent many more hours than anyone else hearing testimony.

One might say the Warren Commission was the first formal investigation of the CIA, but it was really a cursory inquiry more designed to protect the CIA’s reputation, aided by Dulles’s strategic position where he could protect the CIA’s secrets. Dulles never told the other commission members the oh-so-relevant fact that the CIA had been plotting to knock off leftist leaders for a decade, nor did he mention the CIA’s then contemporary assassination plots against Castro. Dulles made sure the commission never took a hard look in the CIA’s direction.

Fighting Exposure

In 1964, another wave of attention came to the CIA from Random House’s publication of The Invisible Government, by David Wise and Thomas B. Ross, who sought to expose, albeit in a friendly way, some of the CIA’s abuses and failures. Despite this mild treatment, the CIA considered buying up the entire printing, but ultimately decided against it. That CIA leaders thought to do that should have rung alarm bells, but no one said anything.

Then, in 1967, an NSA scandal broke, but then the NSA referred to the National Student Association. Ramparts, the cheeky publication of eccentric millionaire Warren Hinckle, found out that the CIA had recruited ranking members of the student group and involved some of them in operations abroad.

By 1967, the CIA also was using these student leaders to spy on other students involved in Vietnam War protests, a violation of the CIA’s charter which bars spying at home. A reluctant Congress had approved the creation of the CIA in 1947 on the condition that it limit its operations to spying abroad for fear it would become an American Gestapo.

However, when these illegal operations were exposed, no one went to jail. No one was punished. Sure, the CIA was embarrassed again, and CIA insiders who consider maintaining the secrets of the agency as nearly a religious endeavor might have felt simply exposing such operations was punishment enough. But it wasn’t.

During the Vietnam War, the CIA ran a wide range of controversial covert operations, including the infamous Phoenix assassination program which targeted suspected Viet Cong sympathizers for death. Meanwhile, Air America operations in Laos implicated the agency in heroin trafficking. The CIA and its operatives also continued to entangle themselves in sensitive activities at home.

President Richard Nixon recruited a team of CIA-connected operatives to undertake a series of politically inspired break-ins, leading to the arrest of five burglars inside the Watergate offices of the Democratic National Committee on June 17, 1972. Nixon then tried to shut down the investigation by citing national security and the CIA’s involvement, but the ploy failed.

After more than two years of investigations – and with the nation getting a frightening look into the shadowy world of government secrecy – Nixon resigned on Aug. 9, 1974. He was subsequently pardoned by his successor, Gerald Ford, who had served on the Warren Commission and had become America’s first unelected president, having been appointed Vice President after Nixon’s original Vice President, Spiro Agnew, was forced to resign in a corruption scandal.

The intense public interest about this secretive world of intelligence opened a brief window at mainstream news organizations for investigative journalists to look into stories that had long been off limits. Investigative journalist Seymour Hersh published revelations in the New York Times about CIA scandals, known as the “family jewels” including domestic spying operations. The CIA’s Operation Chaos not only spied on and disrupted anti-Vietnam War protests but undermined media organizations, such as Ramparts, that had dared expose CIA abuses.

Ford tried to preempt serious congressional investigations by forming his own “Rockefeller Commission,” led by Vice President Nelson Rockefeller. It included such blue bloods as former Warren Commission member David Belin, Treasury Secretary C. Douglas Dillon and California Gov. Ronald Reagan, in other words people who were sympathetic to the CIA and who knew how to keep secrets. But the commission was widely seen in the media as an attempt by Ford to whitewash the CIA’s activities.

Congressional Inquiries

So the Senate convened a committee led by Sen. Frank Church, D-Idaho, called the United States Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities but more commonly known as the “Church Committee,” and the House convened a House Select Committee on Intelligence Oversight led originally by Lucien Nedzi, D-Michigan.

Some House Democrats, Rep. Michael Harrington of Massachusetts in particular, complained that Nedzi was too friendly with the CIA and challenged his ability to lead a thorough investigation. Nedzi had been briefed two years earlier on some of the CIA’s illegal activities and had done nothing. Although the House voted overwhelmingly (and disturbingly) to keep this friend of the CIA in charge of the committee examining CIA activities, under pressure, Nedzi finally resigned.

Rep. Otis Pike, D-New York, took over what became known as the “Pike Committee.” Under Pike, the committee put some real teeth into the investigation, so much so that Ford’s White House and the CIA went on a public-relations counterattack, accusing the panel and its staff of recklessness. The CIA’s own historical review acknowledged as much:

“Confrontation would be the key to CIA and White House relationships with the Pike Committee and its staff. … [CIA Director William] Colby came to consider Pike a ‘jackass’ and his staff ‘a ragtag, immature and publicity-seeking group.’ … The CIA Review Staff … pictured the Pike staffers as ‘flower children, very young and irresponsible and naïve.’ …

“Donald Gregg, the CIA officer responsible for coordinating Agency responses to the Pike Committee, remembered, ‘The months I spent with the Pike Committee made my tour in Vietnam seem like a picnic. I would vastly prefer to fight the Viet Cong than deal with a polemical investigation by a Congressional committee, which is what the Pike Committee [investigation] was.’ …

“As for the White House, it viewed Pike as ‘unscrupulous and roguish.’ Henry Kissinger, while appearing to cooperate with the committee, worked hard to undermine its investigations and to stonewall the release of documents to it. Relations between the White House and the Pike Committee became worse as the investigations progressed. …

“The final draft report of the Pike Committee reflected its sense of frustration with the Agency and the executive branch. Devoting an entire section of the report to describing its experience, the committee characterized Agency and White House cooperation as ‘virtually nonexistent.’ The report asserted that the executive branch practiced ‘footdragging, stonewalling, and deception’ in response to committee requests for information. It told the committee only what it wanted the committee to know. It restricted the dissemination of the information and ducked penetrating questions.”

Punishing Pike

Essentially, the CIA and the White House forbade the Pike report’s release by leaning on friendly members of Congress to suppress the report, which a majority agreed to do. But someone leaked a copy to CBS News reporter Daniel Schorr, who took it to the Village Voice, which published it on Feb. 16, 1976.

Mitchell Rogovin, the CIA’s Special Counsel for Legal Affairs, threatened Pike’s staff director, saying, “Pike will pay for this, you wait and see … We [the CIA] will destroy him for this. … There will be political retaliation. Any political ambitions in New York that Pike had are through. We will destroy him for this.”

And, indeed, Pike’s political career never recovered. Embittered and disillusioned by the failure of Congress to stand up to the White House and the CIA, Pike did not seek reelection in 1978 and retired into relative obscurity.

But what did Pike’s report say that was so important to generate such hostility? The answer can be summed up with the opening line from the report: “If this Committee’s recent experience is any test, intelligence agencies that are to be controlled by Congressional lawmaking are, today, beyond the lawmaker’s scrutiny.”

In other words, Otis Pike was our canary in the coal mine, warning us that the national security state was literally out of control, and that lawmakers were powerless against it.

Pike’s prophetic statement was soon ratified by the fact that although former CIA Director Richard Helms was charged with perjury for lying to Congress about the CIA’s cooperation with ITT in the overthrow of Chilean President Salvador Allende, Helms managed to escape with a suspended sentence and a $2,000 fine.

As Pike’s committee report stated: “These secret agencies have interests that inherently conflict with the open accountability of a political body, and there are many tools and tactics to block and deceive conventional Congressional checks. Added to this are the unique attributes of intelligence — notably, ‘national security,’ in its cloak of secrecy and mystery — to intimidate Congress and erode fragile support for sensitive inquiries.

“Wise and effective legislation cannot proceed in the absence of information respecting conditions to be affected or changed. Nevertheless, under present circumstances, inquiry into intelligence activities faces serious and fundamental shortcomings.

“Even limited success in exercising future oversight requires a rethinking of the powers, procedures, and duties of the overseers. This Committee’s path and policies, its plus and minuses, may at least indicate where to begin.”

The Pike report revealed the tactics that the intelligence agencies had used to prevent oversight, noting the language was “always the language of cooperation” but the result was too often “non-production.” In other words, the agencies assured Congress of cooperation, while stalling, moving slowly, and literally letting the clock run out on the investigation.

The Pike Committee, alone among the other investigations, refused to sign secrecy agreements with the CIA, charging that as the representatives of the people they had authority over the CIA, not the other way around.

Pike’s Recommendations

The Pike Committee issued dozens of recommendations for reforming and revamping the U.S. intelligence community. They included:

– A House Select Committee on Intelligence be formed to conduct ongoing oversight of intelligence agencies. This now exists, although it has often fallen prey to the same bureaucratic obfuscations and political pressures that the Pike Committee faced.

– “All activities involving direct or indirect attempts to assassinate any individual and all paramilitary activities shall be prohibited except in time of war.” We are now in a perpetual state of war against the (so we are told) omnipresent threat of terrorism, meaning that assassinations (or “targeted killings”) have become a regular part of American statecraft.

– “The existence of the National Security Agency (which to that time had been a state secret) should be recognized by specific legislation and that such legislation provide for civilian control of NSA. Further, it is recommended that such legislation specifically define the role of NSA with reference to the monitoring of communications of Americans.” As NSA contractor Edward Snowden exposed last year, the NSA is collecting metadata on the communications of virtually every American and many others across the globe.

– A true Director of Central Intelligence be established to coordinate information sharing among the numerous intelligence agencies and reduce redundant collection of data. After the 9/11 attacks, Congress created a new office, the Director of National Intelligence, to oversee and coordinate the various intelligence agencies, but the DNI has struggled to assert the office’s authority over CIA and other U.S. intelligence fiefdoms.

Not all of the Pike Committee’s recommendations appeared sound. For example, the committee recommended abolishing the Defense Intelligence Agency and transferring all control of covert operations to the CIA. President Kennedy had expressly created the DIA as a way to take unregulated CIA activities out of the hands of the cowboys who ran unaccountable operations with untraceable funds and put them under the control of the (then) more orderly and hierarchically controlled Pentagon.

Possibly, the most important recommendation, because it could have such a far-reaching impact, was this: “The select committee recommends that U.S. intelligence agencies not covertly provide money or other valuable considerations to persons associated with religious or educational institutions, or to employees or representatives of any journal or electronic media with general circulation in the United States or use such institutions or individuals for purposes of cover. The foregoing prohibitions are intended to apply to American citizens and institutions.”

In other words, the Pike Committee wanted the CIA to stop paying journalists and academics to cover for U.S. intelligence and to stop providing cover for U.S. spying and propaganda operations. The committee also recommended that intelligence agencies “not covertly publish books or plant or suppress stories in any journals or electronic media with general circulation in the United States.”

Otis Pike’s final and lasting legacy may be that he tried to warn the country that the American Republic and its democratic institutions were threatened by an out-of-control national security state. He thought there might be a solution if Congress asserted itself as the primary branch of the government (as the Framers had intended) and if Congress demanded real answers and instituted serious reforms.

But the Ford administration’s successful pushback against Pike’s investigation in 1975-76 – a strategy of delay and deflection that became a model for discrediting and frustrating subsequent congressional inquiries into intelligence abuses – represented a lost opportunity for the United States to protect and revive its democracy.

Though Otis Pike failed to achieve all that he had hoped – and his contribution to the Republic faded into obscurity – the reality that he uncovered has become part of America’s cultural understanding of how this secretive element of the U.S. government functions. You see it in the “Bourne” movies, where an abusive national security elite turns on its own agents, and in ABC’s hit series “Scandal,” where a fictional branch of the CIA, called B613, is accountable to no one and battles even the President for dominance.

At one point in the TV show, the head of B613 refuses to give information to the President, saying: “That’s above your pay grade, Mr. President.” It’s a storyline that Otis Pike would have understood all too well.

Lisa Pease is a writer who has examined issues ranging from the Kennedy assassination to voting irregularities in recent U.S. elections.