What Lessons Can Vietnam teach Okinawa about U.S. Military Dioxin?

In December 2015, Urasoe City pledged to conduct a survey of former base employees to ascertain the extent of contamination at Camp Kinser, a 2.7 square kilometer US Marine Corps supply base located in the city.1 Urasoe’s director of planning, Shimoji Setsuo, announced that the municipality would work with prefectural authorities to carry out the investigation and he would also request funding from the national government. This is believed to be the first time that such a large-scale survey of former base workers has been launched in Japan.

Triggering Urasoe’s decision were Pentagon documents released under the U.S. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) revealing serious contamination at Camp Kinser.2 According to the reports, military supplies returned during the Vietnam War leaked substances including dioxin, polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and insecticides within the base, killing marine life. Subsequent clean-up attempts were so ineffective that U.S. authorities worried that civilian workers may have been poisoned in the 1980s and, as late as 1990, they expressed concern that toxic hotspots remained within the installation.

Following the FOIA release, United States Forces Japan (USFJ) attempted to allay worries about ongoing contamination at Camp Kinser. Spokesperson Tiffany Carter told The Japan Times that “levels of contamination pose no immediate health hazard,” but she refused to provide up-to-date environmental data to support her assurances. Asked whether USFJ would cooperate with Urasoe’s survey, Carter replied that they had not been contacted by city authorities. She also ruled out health checks for past and present Camp Kinser military personnel.3

Last year, suspicions that Camp Kinser remains contaminated were heightened when wildlife captured by Japanese scientists near the base was found to contain high levels of PCBs and the banned insecticide DDT.4

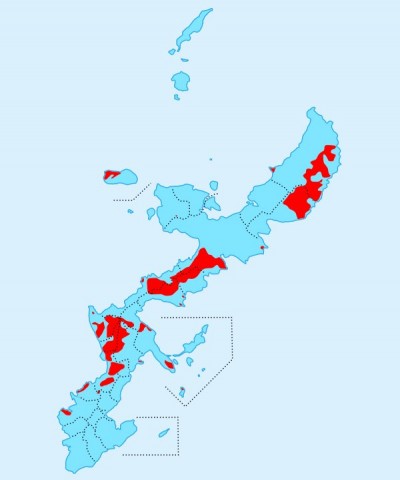

Japanese officials are blocked from directly investigating pollution in U.S. bases because the Japan-U.S. Status Of Forces Agreement does not authorize them access. Although an amendment to the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) last September gave Japanese authorities the right to request inspections following a toxic spill or imminent return of land, permission remains at the discretion of the U.S.5 Consequently, until now research has been limited to land already returned to civilian usage. These checks suggest that the problem of U.S. military contamination on Okinawa is chronic. In recent years, a range of toxins exceeding safe levels have been discovered on the island such as mercury, lead and cadmium.6

|

Three generations of suffering: Former South Vietnamese Army soldier Le Van Dan (left) blames the U.S. military for the health problems afflicting himself and his family. He suffers from skin and heart diseases, his daughter struggles to breathe, one grandchild has cerebral palsy, and another is bedridden. |

In November, the Okinawa Defense Bureau revealed that a housing area in Kamisedo, Chatan Town, was contaminated with dioxin at levels 1.8 times environmental standards. The problem came to light after residents complained of offensive smells emanating from the land which used to be a U.S. military garbage dump prior to return in 1996.7 Meanwhile, in December, Japanese officials released test results on three more barrels unearthed from the Pentagon’s defoliant dumpsite in Okinawa City. The barrels, the latest of 108 found beneath a children’s soccer pitch, measured dioxin levels between 83 and 630 times environmental standards.8

The World Health Organization categorizes dioxin as “highly toxic” and links it to cancer, damage to the immune system and reproductive and developmental problems.9

On Okinawa, awareness of the dangers of dioxin is low. Last year in Okinawa City, for example, laborers at the former soccer pitch were photographed working without safety equipment, and storm water was pumped into a local conduit without any tests for contamination.10

Now expert advice is coming from a country with tragic experience of Pentagon dioxin poisoning: Vietnam.

“On Okinawa, people still don’t know about the risks. The problem is very new for them but they need to take action as soon as possible,” Phan Thanh Tien, Vice President of the Da Nang Association for Victims of Agent Orange / Dioxin (DAVA), said last month.

Created in 2005, DAVA has been raising Vietnamese people’s awareness of the dangers of dioxin left in the environment from the Pentagon’s usage of defoliants in the Vietnam War. Between 1962 and 1971, during Operation Ranch Hand, the U.S. military sprayed 76 million liters of herbicides in southeast Asia. Named after the colored stripes around the barrels, many of these herbicides such as Agents Pink, Purple and – by far the most common – Orange, were heavily contaminated by dioxin during the production process.11

During the Vietnam War, U.S. forces stored approximately 18 million litres of defoliants at Da Nang Airbase and sprayed them over nearby countryside to kill food crops and strip supply routes of jungle cover. The Pentagon particularly targeted rice, sweet potato and cassava crops.

According to U.S. veterans, these defoliants were shipped via Okinawa, America’s most important staging post for the Vietnam War.12 Former service members contend that defoliants were stockpiled at numerous bases – including Camp Kinser, then known as Machinato Service Area – and sprayed to keep runways and perimeter fences clear. Veterans also claim that surplus and damaged barrels of defoliants were buried within Okinawa’s bases.

These burials allegedly took place at Kadena Air Base, Camp Schwab, MCAS Futenma and Hamby Yard, in Chatan Town. At the time, the burial of surplus chemicals – including Agent Orange – was official U.S. military policy. For example, the FOIA documents detailing contamination at Camp Kinser also describe the burial of 12.5 tons of ferric chloride on the installation and the disposal of pesticides at Camp Hansen, Kin Town.

U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs records show more than 200 retired service members are sick with illnesses they believe are caused by exposure to Agent Orange on Okinawa. A number of military documents corroborate their claims. These include a U.S. army report citing the presence of 25,000 barrels of the defoliant on the island prior to 1972 and the latest FOIA release which describes the discovery of “dioxin (agent orange component)” at Camp Kinser.13

|

“America’s use of Agent Orange in Vietname was a war crime; it was chemical warfare. Today, we are starting to see the fourth generation of victims, so you can even call it a form of biological warfare”, says Pha Hanh Tien, vice-president of the Da Nang Association For Victims of Agent Orange/Dioxin. |

Despite this evidence, the Department of Defense continues to deny that Agent Orange was ever on the island. In 2013, it published a report which concluded that there were no “records to validate that Herbicide Orange was shipped to or through, unloaded, used or buried on Okinawa.” The report caused anger among U.S. veterans claiming dioxin exposure on Okinawa since none of them was interviewed for the report, nor were any environmental tests of Okinawa bases conducted.14 The same Pentagon-funded scientist who wrote the report later attributed the discovery of dioxin beneath Okinawa City’s soccer pitch to the disposal of kitchen or medical waste.15

Such denials do not surprise DAVA vice president Phan. For decades, he explained, the U.S. government has been trying to mislead people about the impact of dioxin in Vietnam, too. For example, during the war, it assured people that defoliants would only harm trees.

“They lied. They knew about the human impact but they said nothing,” said Phan.

According to DAVA, today there are approximately 5,000 dioxin victims in Da Nang, which has a total population of 1 million. Nationwide, the Vietnamese Red Cross calculates 3 million are sick; DAVA estimates the number as closer to 4 million.16 DAVA – and the national organization Vietnam Association for Victims of Agent Orange / Dioxin – helps these survivors with vocational training, rehabilitative therapy and business start-up loans.

Le Van Dan is one of those helped by DAVA – and he knows firsthand the truth that contradicts the Pentagon’s lies.

During the war, he fought on America’s side in the South Vietnamese Army and he witnessed U.S. planes spraying the mountain ridges near Da Nang; later he saw the dead trees left in their wake. The U.S. military had assured the Vietnamese public that the spray was harmless so he and his fellow soldiers drank the local water and ate the fruit and vegetables. Today, the 66-year old suffers from skin and heart diseases, his daughter struggles to breath, one grandchild has cerebral palsy and another is bedridden.

Vietnam’s Ministry of Health categorizes 17 illnesses as related to dioxin – including cancers of the prostate and lung, type 2 diabetes and spina bifida. The U.S. government recognizes a similar list of dioxin-linked diseases – and it compensates sick American veterans who served in Vietnam. But it does nothing to help dioxin-poisoned Vietnamese people.17

The U.S. government’s refusal to acknowledge the human impact of Operation Ranch Hand angers Phan: “America’s use of Agent Orange in Vietnam was a war crime; it was chemical warfare. Today, we are starting to see the fourth generation of dioxin victims so you can even call it a form of biological warfare. And the problem still isn’t over.”

A number of dioxin hotspots remain on former U.S. military land in Vietnam; one of them is at Da Nang Air Base, today the site of the city’s international civilian airport. Although the U.S. government refuses to recognize the human impact of its dioxin in Vietnam, at Da Nang Airport it has engaged in environmental clean-up work since 2012. The estimated date of completion is later this year.18

Many have praised the cleanup as a positive first step – albeit one that is long overdue. The U.S. has also promised to help to remediate dioxin hotspots in other former bases in Vietnam.

This stands in stark contrast to Japan, including Okinawa, where SOFA places the financial burden of cleaning up U.S. military contamination entirely on Japanese taxpayers – and Tokyo has made no attempts to make the U.S. more responsible.

In November 2014, Phan visited Okinawa to attend the island’s first international symposium about military contamination and the inadequacies of SOFA.19 When he inspected the dioxin dumpsite in Okinawa City, he noted that it carried the same distinct odor as Da Nang Airport’s hot-spot. Given Japan’s reputation for technological expertise, Phan was surprised by the low safety standards at the site such as the lack of warning signs and tarpaulins to prevent the spread of contaminated dust.

Now Phan worries about what Urasoe’s base workers’ survey might uncover.

“When Da Nang airport was enlarged before 2007, the workers didn’t wear protective gear so they were exposed to dioxin. Prior to working at the site, these men had children born in perfect health. But afterwards, a number of them had children born with cerebral palsy and mental deficiencies,” he said.

Phan’s message for Okinawan authorities is clear.

“First they need to prevent the spread of dioxin from the dumpsite to outside. Stop pumping waste water into the river. Then they need to inform the public of the problem. Finally there needs to be research to check the health of residents in the area – particularly the children.”

Phan believes Urasoe’s survey is a move in the right direction. But to fully address the issues, action must originate from the national level.

“The Japanese government needs to research and push America to reveal the truth. But the Japanese government doesn’t want to damage its relationship with America. This is why they stay silent – even when Okinawa’s land is poisoned by dioxin.”

In May 2015, Welsh journalist, Jon Mitchell, was awarded the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan Freedom of the Press Award for Lifetime Achievement for his reporting about human rights issues – including military contamination – on Okinawa. He is the author of Tsuiseki: Okinawa no Karehazai(Chasing Agent Orange on Okinawa) (Kobunken 2014) and a visiting researcher at the International Peace Research Institute of Meiji Gakuin University, Tokyo. Mitchell is an Asia-Pacific Journal contributing editor. This is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared in The Japan Times.