“We Have the Right to Live”: NATO’s War on Yugoslavia and the Expulsion of Serbs from Kosovo

Sixteenth Anniversary of the NATO Attack

In the period before the 1999 NATO attack on Yugoslavia, the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) waged a campaign to secede and establish an independent Kosovo dominated by Albanians and purged of every other ethnic group. In October 1998, KLA spokesman Bardhyl Mahmuti spelled the KLA’s vision: “We will never change our position. The independence of Kosovo is the only solution…We cannot live together [with Serbs]. That is excluded.”

Once NATO’s war came to an end, the KLA set about driving out of Kosovo every non-Albanian and every pro-Yugoslav Albanian it could lay its hands on. The KLA left in its wake thousands of looted and burning homes, and the dead and dying.

Two months after the end of the war, I visited Hotel Belgrade, located on Mt. Avala, a short distance outside of Belgrade. Those who had been driven from their homes in Kosovo were housed in hotels throughout Yugoslavia, and in this one lived Serbian refugees.

The moment I entered the hotel, the sense of misery overwhelmed me. Children were crying, and the rooms were packed with people. The two delegation members who accompanied me and I were shown all three floors, and the anger among the refugees was so palpable I felt I could reach out in the air and touch it. Nearly everyone here had a loved one who had been killed by the Kosovo Liberation Army. All had lost their homes and everything they owned.

Initially, many of them refused to talk with us, and one refugee demanded of me in a mocking tone, “Can you get my home back?” It was not until a while later that we discovered that due to a misunderstanding, some of the refugees thought the NATO commander of the attack on Yugoslavia, Wesley Clark, had sent us there. We were quick to correct that misapprehension, and then people were more inclined to talk with us. There was still, however, some residual reluctance based on three prior experiences these refugees had with Western visitors, all of whom had treated them with arrogance and contempt. A reporter from the Washington Post was said to have been particularly abusive and insulting.

Several refugees were too upset to talk. The eyes of one woman and her son still haunt me. I could see everything in their eyes – all that they had suffered.

We climbed the stairs to the third floor and began our interviews there. A family of seven people were crowded into the first room we stopped at. We were told that five of them slept at night on the two beds, and the other two on the floor. Goran Djordjevich told us his family left Kosovo on June 13. “We had to leave because of the bandits. They threatened to kill us, so we had to leave. The moment NATO came we knew that we would have to leave.” After having talked with Roma and pro-Yugoslav Albanian refugees on earlier occasions, his family’s story was a familiar one to us by now, in that threats from KLA soldiers had prompted a hasty departure.

“We not only had a house, but also our farm and our property,” Djordjevich continued. “We just let the cattle free and we fled. I drove the tractor from our village to Belgrade for four nights and five days. When our army withdrew and NATO came in, we followed the army. You know, the Albanian bandits were there all the time in the surrounding forest and the moment NATO advanced, they just joined them and started terrorizing us. They were shooting at us but we were the lucky ones because we were with the army; so we were safer, but the ones who left later were in jeopardy. Very soon after we left our house they came to the village and burned the whole village, razing it to the ground. They were firing and burning everything.”

One young man who appeared to be about twenty years-old would not give his name, but spoke to us in halting English. “The American leader is very bad. He killed too many children. Too many bombs. Too many old men. He’s guilty for too much death. I was in Kosovo when the American Air Force bombed and killed our children. They wanted to kill our children; not just our soldiers. They wanted to kill our people. For them it was just a game”

The young man witnessed a startling development when he encountered NATO’s Kosovo Force (KFOR). “When our soldiers, our boys, started to withdraw from Kosovo, KFOR came in. The first soldiers were American soldiers and German soldiers. They took the weapons from the Serbian people, and in front of our eyes, gave them to the Albanian people to kill the Serbian people. We saw that.” I asked, “You saw KFOR turning arms over to the KLA?” The youth replied, “Yes. And giving them to KLA terrorists.”

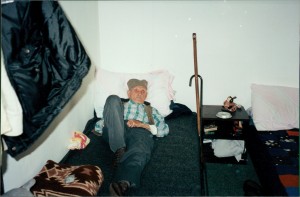

At the end of the hall, a family of eight was packed into a single room, their mattresses arranged side-by-side from one end of the room to the other. An eighty year-old man reclined on a mattress, his cane nearby. His silence conveyed an aura of deep sorrow. Mitra Dragutinovich said they left Kosovo on June 11. “We knew that the moment the army left Kosovo, then the KLA would take over. The terrorists started threatening, killing, and shooting. Many people were wounded. Our cousin is a pediatrician, and an Albanian woman came to his office with a child and took a gun from her trousers and wounded him, He lost a kidney. Pointing to the eighty year-old man, she said, “The pediatrician who was wounded is his grandson.”

A woman approached, and with rising emotion addressed us in a sharp tone. “Why did the Americans and the Germans come? Why did they come? Did they come to protect us, or did they come to massacre us, to drive us from our homes, to violate our women, and to kill our children? I can’t believe that someone who had first bombed you for three months, every day and for 24 hours, that after that he will come to protect you. I wonder how [US President] Clinton can’t be sorry for the children at least. Are there children in your country? Does he know what it means to be a child? You know, we could retaliate. We could also organize terrorist actions and kill your children in the United States. But we are people with a soul. We would never, never, do that to any American child, because we are people with a soul.”

I asked what life had been like in her village during the bombing, and she answered, “It was awful. We were frightened. We were in our country. We were on our soil. But now, we are no longer on our soil, because we are occupied down there. Whoever they are, be they Americans, British, Germans, French, let them take care of their own problems at home and we shall deal with our problems here, in our country, because this is our country.”

We returned to the first floor, where we found a small crowd gathered in the lobby. Nikola Cheko was from Velika Hocha, near Orahovac. He had a strikingly expressive manner of speaking that I found quite moving, injecting each word with intense and sincere feeling. “We were surrounded from the very beginning of the aggression on March 24. We were surrounded by the Albanians. No electricity. No water. No bread. None of the conditions necessary for life. No one is taking care of us. KFOR: Nothing! They couldn’t care less for poor Serbs. They think we are stupid farmers; we’ll survive somehow and no one needs us, so KFOR simply forgets us. It’s a shame. It’s a shame for KFOR, for the United States, for Great Britain, for France, for Germany, for NATO, and all the big powers of the world. We are all human beings. We have the right to live. The nationality, the race and the religion are not important at all. A human being should first be a human being. A true human being is the one who is ready to help the victim in need. I think that KFOR should open its eyes and see what’s going on down there and behave according to Resolution 1244 and the documents signed by our Yugoslav representatives and the UN representatives in Kumanovo. In Kosovo, it’s not only Velika Hocha that is in trouble. There are many, many villages where people are absolutely in great need and dying. It’s high time that we become human beings and behave like human beings in the first place.”

Emotions in the room were running quite high and it took considerable prodding and encouragement to get anyone else to talk. My entreaties were met with silent rejection and it was at this point that our translator discovered that everyone thought that NATO general Wesley Clark had sent us. Once our translator cleared up that matter, the people were still disinclined to speak.

A woman in her thirties shouted out, “I don’t want to talk because no one will help. Two of my brothers have been kidnapped.” It was an opening, and I explained that the American people were unaware of what was happening, and that is why we wanted these interviews. Her name was Biljana Lazich, from Sopin, and pretty soon she began to talk more freely. “You know, we are all dressed in black [for mourning]. When Kosovo was part of Serbia and when our army was there, the KLA took my brothers prisoner. They were farmers and they were kidnapped from their homes. We didn’t hear anything from them for a whole year. My mother did everything possible and impossible, through the tracing service of the Yugoslav Red Cross and International Red Cross. The International Red Cross informed us that my brothers were alive and that they would be exchanged. It was in July last year, ten days after they had been taken prisoner.”

But nothing happened. Months passed and one day Lazich’s mother visited William Walker, who had been installed at U.S. insistence as head of the OSCE Kosovo Verification Mission. The ostensible purpose of the OSCE mission was to reduce the level of conflict between the Yugoslav security forces and the KLA, but the signed agreement applied only to Yugoslavia. The KLA was not part of the agreement, and was free to run wild. Walker packed the mission with CIA agents, who were busy marking targets for the impending NATO attack and providing military training to the KLA. Shortly before departing Kosovo, they handed communications and satellite global positioning equipment to the KLA.

Walker was unresponsive to the pleas, Biljana Lazich told us, and “didn’t say anything.” He was just “beating around the bush,” and “nothing happened.”

Life during the bombing was “awful, awful,” she continued. “We were frightened, both of the bombs coming from the sky and of the KLA. Before the war and the bombing, we had good relations with our neighbors. But when the bombing started, we knew what was in store for us, because we knew the intent of the KLA. We were afraid of the KLA and we wouldn’t allow our kids to leave our houses. They were all locked inside. We didn’t allow the children to play outside at all. We were particularly afraid for the children. The situation was unbearable! We had to flee, to save the children at least.”

Lazich introduced her mother-in-law, Dobrila Lazich, who told us what the KLA had done to her brother’s 13-year-old son in September 1998. The boy “came to see his relatives. First, he came to see one aunt and uncle and then he went to visit the other aunt and uncle, and between the two houses he was kidnapped and killed.” The boy’s mother was reluctant to talk to us, but her relatives pushed her forward and she spoke in a barely audible voice. Her name was Stana Antich and she told us how she sought help from William Walker, but he would not do anything.

At this point, Biljana stepped forward and interjected, “The boy was only 13-years-old. How could he be guilty to anyone? He’s just 13. I have a brother-in-law who was beaten to death, in Dragobilje.” The OSCE Kosovo Verification Mission “knew they were taken prisoner and they communicated to us that they were alive and well, but finally we got their dead bodies.” A third man “was returned alive, but unconscious and very severely beaten.”

Despite some honest members, as a general rule nothing could have been expected from the leadership of an OSCE mission that was riddled with CIA agents. I asked the question that I already could guess the answer to. What did the OSCE Verification mission do in response to these murders? “Nothing,” Biljana responded. “Nothing. They were just sitting idle, waiting for them to beat them to death. They didn’t intervene. They didn’t come to help us. They just came to help the KLA.” Biljana spoke of how people disappeared or were killed outright. “The whole world knew that, but no one wanted to condemn the KLA for these crimes. They put all blame on the Serbian police, constantly accusing them of persecuting the Albanians.”

Dostena Filipovich appeared to be in her sixties and wore a scarf over her head. She told us how she had sent her three children out of Kosovo to ensure their safety. “My husband and I, as elderly people, stayed back to protect and defend the house. Since there were few Serbs who stayed behind in our village, some Albanians started molesting us, threatening and firing guns in front of our windows, so we decided to leave our village. We took only hand luggage and our cow and went to a neighboring village. We have only what we are wearing. We had a lot of poultry. We had a lot of cattle. We didn’t let them loose. We just locked them in the stable and the chicken coop, expecting to return. You remember I said that we decided to go to another Serbian village, but when we arrived there, the people were also fleeing. Since the roads were jammed, we couldn’t move fast and we wanted to go to Brecovica but the roads were so jammed we couldn’t move from Prizren. Even though KFOR was in Prizren, the KLA attacked us in Prizren, firing on our column.” I asked, “And KFOR did nothing?” The tone of Filopovich’s response indicated that she was still astonished to that day. “Nothing! Nothing! Just watching and laughing, watching and laughing.”

The column of refugees eventually made their way to another Serbian village to stay overnight, but at 3:00 AM they heard gunfire in the surrounding area and decided to leave. They arrived at another village, populated by both Serbs and Albanians. “When we arrived in that village, three KLA soldiers wearing different colors of caps came, together with KFOR.” Nevertheless, the refugees spent two nights in the village. “Serbs were not allowed to stand guard. Only local Albanians were allowed to stand guard. Then KFOR called all the Serbian men to surrender their weapons to KFOR. KFOR then handed all the weapons over to the KLA.” Once that happened, it was clear to the refugees that they would have to leave. “KFOR organized our column, one tank in front and the other in back. And then we noticed a lorry full of Albanians came. They were our neighbors. They smeared their faces so as not to be recognized, but we recognized them all the same. They wanted to plunder us. To be honest, KFOR did not allow them to do so. We were honest people. We didn’t have trouble with the neighbors. We didn’t take anything from anyone, so our consciences were quite clear. We thought that we should be protected, as honest people.”

First KFOR collected all out weapons, so we were easy prey. Before my eyes, the KLA killed my uncle. Actually, they slaughtered him with an axe and left his body. They didn’t bury him. They cut him into pieces. KFOR simply doesn’t prevent the KLA from doing anything. They can do anything. They just simply sit and watch and do nothing. We were not allowed to protect ourselves. We were driven out of our own homes. We were unarmed. We were at the mercy of the KLA terrorists. They had support from KFOR. They gave them arms. They took the arms from us. We left our homes with our naked souls and nothing else.

I asked if anyone else would like to be interviewed and all declined. There was a young girl in the room, aged around 12 or 13. A couple of people told me that the KLA had murdered her father. Several people encouraged her to talk but she vigorously shook her head no. They asked the girl again, and she broke into tears. With a loud, heart-rending sob, she spun around and fled down the hallway, leaving behind her a trail of echoing cries. Shaken, I stood there in silent contemplation when someone jarred me back to awareness by asking if I wanted the girl brought back. I could not inflict that on her and said no.

Bozhe Antich was sitting on a folding chair. Before he uttered a word, one could sense that terrible things had happened to him. He spoke out, “I have experienced a great tragedy.” We walked over to listen to his story. “It’s difficult for me to talk. I am from the village of Sopin, in the municipality of Suva Reka. The KLA killed my brother’s son. He was 42 years old. They killed him because he was a Serb. They killed my best friend, a mechanic. His name is Ranchel Antich, from Ljeshane village. They also killed Dr. Boban Vuksanovich, director of the health center in Suva Reka. They also killed my daughter-in-law’s brother, 32-years-old, just because he was a Serb. He was killed 200 meters from his home. They were not in politics. They were ordinary workers, mechanics. They went to the monastery to repair a machine there, and the road was bombed. They were on the way to the Holy Trinity Monastery, a very old monastery from the 14th century. They left Suva Reka, on the way to repair the machine. It’s four kilometers from Suva Reka. The KLA ambushed them, first killing the driver of the car. Then they pushed the car down over a cliff. Several of the passengers in the car were wounded. The terrorists were not satisfied with killing the driver, the doctor and my cousin. They wanted to kill everyone in the car. So when the car came to a stop at the bottom of the hill, they followed the car and killed my other nephew with sixteen bullets in his body.”

This incident took place during the NATO war. Not long after the murders occurred, a criminal investigator visited the site and KLA soldiers killed him, too. The Holy Trinity Monastery, where Antich’s friends and family were headed the day they were killed, also met a sad fate. When KFOR entered Kosovo in mid-June 1999, KLA soldiers looted and burned the monastery, and the next month they returned and demolished it with explosives. The Holy Trinity Monastery was one of 84 churches and monasteries the KLA destroyed during its rampage in the first few months under the protective wing of NATO. Many of the buildings dated back to the Middle Ages, and some were designated by UNESCO as world historic sites. KFOR would eventually place under guard some of the more historic sites that had managed to survive, but the demolition of religious sites nevertheless continued on a sporadic basis. In March 2004, Albanian extremists launched a new pogrom, killing, beating and driving away Serbs and setting their homes ablaze. During those attacks, another 35 churches and monasteries were destroyed or damaged.

“We can’t go back as long as the KLA has KFOR protection, a shield for their murderous activities,” Bozhe Antich explained. “If someone is human, he should at least be sorry for the little children who have been murdered. Because all the children of this world are children in the first place, regardless of their religion, race, and ethnic origin. What is the future of our children now? They have no homes. They have no schools for now. We were not poor people. We had our property down there. We had houses. We had land. For example, in my case, I worked for 33 years. Now, I am a beggar. I have nothing. Our country, Serbia, is in deep economic crisis. Serbia cannot help. What is our future? All those supporting these criminal activities, committed by Albanian terrorists, should face the truth and see in us human beings, because we are human beings.”

Sava Jovanovich presented photographs of his demolished home in Kosovo. Scrawled on one wall was ‘UCK’, the initials for ‘KLA’ in the Albanian language. Another graffiti message read, “Return of Serbs prohibited.” Jovanovich and his four brothers lived in houses that were next to each other. They left Kosovo on June 11 and 12. “It was an exodus,” Sava recalled. “My father decided to protect the houses. I asked about my father, and they told me, “We don’t know anything. We have no news from him. We don’t know.” The KLA “took everything, all the wheat, and then they burned down the granary. They also plundered the wheat and corn from my brothers’ property and then burned down the building. We had about 15 cows, 20 pigs, and lots of poultry, and now we have nothing.”

The lack of news of his father’s fate distressed him, and he blamed Western intervention for the tragedy that had befallen his family. “My father remembers the stories from his grandfather, from the time when he lived while the region was still under the Ottoman Empire. And my father lived under German occupation during the [Second] World War. They didn’t have to leave their homes. Now is the first time we were forced to leave. It is worse than under the Ottomans and the Germans.”

I mentioned to him that U.S. officials were saying that members of the KLA could join the new police force being established in Kosovo. Jovanovich was startled. “This is impossible, because they hate the Serbs and they are against the Serbs. This is not possible.” But that is precisely what happened, as KLA soldiers filled the ranks of the newly formed police force in NATO-occupied Kosovo.

About one month after I returned to the United States, I read an article from the Yugoslav press. A reporter had interviewed many of the same refugees at Mt. Avala, including Sava Jovanovich. In the intervening time, Jovanovich had finally received news of his father. “I heard that Albanian robbers hanged my father, who didn’t want to leave, at his doorstep.”

Gregory Elich is on the Board of Directors of the Jasenovac Research Institute and the Advisory Board of the Korea Policy Institute. He is a columnist for Voice of the People, and one of the co-authors of Killing Democracy: CIA and Pentagon Operations in the Post-Soviet Period, published in the Russian language.