War Crimes and the US Congress: Drone Victims Tell Empty US House Their Story; Is America Listening?

“We do not kill our cattle the way the US is killing humans in Waziristan with drones.”– Rafiq ur Rehman“I no longer love blue skies. In fact, I now prefer grey skies. The drones do not fly when the skies are grey.”– Zubair Rehman,

“Now, I am always scared.” – Nabila Rehman,

Pakistani school teacher Rafiq ur Rehman traveled over 7,000 miles with his children – 13-year-old Zubair and 9-year-old Nabila – from a small, remote village in North Waziristan to tell lawmakers about the US drone strike that killed his 67-year-old mother, Mamana Bibi. It was a harrowing tale that brought many in the room to tears, including Rep. Alan Grayson (D-Fla.), who was responsible for inviting the family to Capitol Hill for the briefing.

In the end, only five members of the US House of Representatives bothered to attend. Grayson was joined by Reps. Jan Schakowsky (D- Ill.), Rush Holt (D-NJ), John Conyers (D-Mich.) and Rick Nolan (D-Minn.).

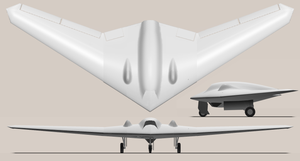

Meanwhile, President Obama, according to his October 29 schedule, was meeting with the CEOs of Lockheed Martin and Northrup Grumman, both of which manufacture drones. More importantly, Lockheed Martin manufactures hellfire missiles, the very weapon fired from the drone that killed Mamana Bibi.

Though Obama did not publicly acknowledge the briefing, his actions the next day suggest he was either unmoved or did not tune in.

Just one day after the Rehman family addressed Congress, a US drone strike killed three people and injured at least three more in North Waziristan. The identities of the dead have yet to be confirmed, but Pakistani intelligence officials say they were suspected militants, the same claim made in the aftermath of Mamana Bibi’s death.

In Their Own Words

“On October 24, 2012, a CIA drone killed my mother and injured my children,” Rehman said, speaking through a translator. And so began the first time members of Congress heard a drone victim tell their story.

“Nobody has ever told me why my mother was targeted that day,” he continued. “Some media outlets reported that the attack was on a car, but there is no road alongside my mother’s house. Others reported that the attack was on a house. But the missiles hit a nearby field, not a house. All of them reported that three, four, five militants were killed. But only one person was killed that day.

“She was the string that held our family together. Since her death, the string has been broken, and life has not been the same. We feel alone and we feel lost.”

Rehman was returning from buying groceries when he learned his mother had been killed. “When I heard this news, all the groceries – the fruits and sweets I had bought – just fell from my hands. It was as if a limb had been cut from my body to hear the news of my mother’s death,” he told Truthout.

“All my neighbors and relatives were telling me to come immediately to the mosque because they were going to start the prayers. But I said no, I want to go to my house, I want to see my mom’s face before they bury her to rest. They were telling me that no, you don’t want to see the condition she is in,” said Rehman. “Later, I realized that because she was blown to pieces, they collected whatever they could and put it in a box. I wanted to see my mom’s face for the last time but they had taken her remains and put it into a box.”

It was the day before Eid and Rehman’s mother was outside with eight of her grandchildren picking okra. Both Zubair and Nabila said they noticed a drone overhead but, as Zubair explained, “I wasn’t worried because we are not militants.”

Nabila described to Truthout what happened next. “All of the sudden I heard this ‘dum dum’ noise, and I saw these two white lights come down and hit right where my grandmother was. Everything had become dark, and it was smelling weird. I was really scared and didn’t know what to do so I started to run, and I just kept running and running,” she said.

“I felt some pain in my hand. When I looked, it was bleeding. I tried to bandage it and wipe it with my scarf to stop the bleeding but the blood just kept coming out. I had lost a lot of blood. Next thing I know I ended up in a hospital and it was evening time.”

Zubair’s experience was equally as horrific. “My grandmother was blown up into pieces, and I got injured in my leg,” he told Truthout. “At the funeral, everyone was trying to console me, saying, ‘We all lost a grandmother.’ There was no one else like her. She would always make sure that we would have something to eat, and she would always make our favorite meals or buy our favorite fruits from the market.”

Zubair has since undergone multiple surgeries to have shrapnel removed from his leg. Medical costs have piled up, forcing Rehman to borrow money and sell his land to pay for treatment. In the meantime, the US government has yet to provide an explanation for the strike or offer any compensation to the family for their loss, which appears to be a widespread problem. The peace group Codepink recently discovered that over the last four years, not a single dime of the $40 million allocated by Congress for that purpose has gone to Pakistani victims of drone strikes.

Rep. Grayson told Truthout he was unaware of the problem but promised to have his office look into it.

Since the briefing, Rehman says no one from the US government has approached him about compensation, though he stressed, “That’s not the reason why I came here. I wasn’t looking for any compensation in any way. What I was coming here to do is tell the truth, to share my story. This is about humanity. This is about the truth. This is about justice.”

The briefing came one week after the release of several scathing reports by human rights organizations and the UN criticizing the US drone program as a violation of international law. The Obama administration responded to the UN by defending the program as “necessary, legal and just.”

Amnesty International, which investigated 45 drone strikes carried out in Pakistan’s North Waziristan region between January 2012 and August 2013, accused the United States of “exploiting the lawless and remote nature of the local region to evade accountability for violations of the right to life.” Amnesty was particularly concerned about “signature strikes,” where drone operators fire on unidentified groups of people based on patterns of behavior that signify militant activity. A signature strike is believed to have killed 18 laborers and injured 22 others in July 2012, according to the report, which also documents several double-taps or follow-up strikes targeting rescuers and mourners. Amnesty concluded that up to 900 civilians have been killed by US drone strikes in Pakistan in “unlawful killings that may constitute . . . war crimes.”

Despite the mounting evidence to the contrary, the White House has insisted that the president requires “near-certainty” that civilians will not be harmed before approving a drone strike, adding that there is a “wide gap” between the administration’s casualty numbers and those of the nongovernmental organizations. Unfortunately, it is impossible to compare the two because the White House refuses to release its data. That being said, if the president’s numbers are significantly lower, it might be related to his definition of the term “militant.” Obama tallies “all military-age males in a strike zone as combatants . . . unless there is explicit intelligence posthumously proving them innocent,” a counting method that surely lowers the casualty number.

Shahzad Akbar, the Rehman family’s attorney who was refused a visa to attend the briefing, told Truthout that Obama administration claims about low civilian casualties are absurd. “Either [Obama] is lying or he is being lied to,” he said.

Akbar is a legal fellow with the British human rights group Reprieve and the director of the Pakistan-based Foundation for Fundamental Rights, where he represents over 150 drone strike victims. “I didn’t expect this from Obama,” he said. “I liked him. I thought that he was the hope of East meets West. He turned out to be the biggest disappointment.” Akbar continued, “Obama’s first drone strike hit a house filled with civilians, and he was informed of this fact. But what does he do? He escalates the drone strikes.”

At the briefing, the lawmakers were asked repeatedly whether certain drone strikes constituted war crimes, as suggested by Amnesty International. All deflected the question except for Grayson, who argued that US drone strikes are not war crimes because the killing of civilians is not “deliberate.”

Asked whether signature strikes, which target unidentified persons, might constitute war crimes, Grayson declined to speculate, calling instead for more transparency. “I do think that there is overwhelming evidence that we need a different, more reliable system if we’re going to be undertaking operations like this,” he told Truthout.

But according to Reprieve attorney Jennifer Gibson, intention is not the only litmus test.

“[Intention] matters to the degree that you are required to be proportionate in your targeting to minimize civilian casualties,” Gibson told Truthout. “To the extent that you’re being deliberately negligent in minimizing civilian casualties, which is the category that signature strikes would fall into, then yes, in certain instances we very well might be committing war crimes.” But there are no agreed-upon parameters for proportionality. Still, Gibson argued, “What I do know is a grandmother and her eight grandchildren is disproportionate.”

“Before, I would hear the drones but I didn’t think much of it. I would just go about my daily life. I’d want to go to school. There would hardly be a time that I would refuse to go outside,” Zubair told Truthout. “But now, after I’ve seen what’s happened to me and my family and that I’ve had two operations, I’m scared. I don’t want to go outside anymore. I don’t feel like playing cricket, volleyball and soccer with my friends. I don’t even want to go to school. I just fear every time I hear the noise overhead.”

Zubair added that there are already too few schools in his community and due to the fear of drone strikes, “students have stopped going to the ones that exist,” echoing a report published last year by Stanford and NYU, in which researchers observed that the presence of US drones buzzing over northwest Pakistan 24 hours a day “terrorizes men, women and children, giving rise to anxiety and psychological trauma among civilian communities,” who “have to face the constant worry that a deadly strike may be fired at any moment and the knowledge that they are powerless to protect themselves.” As a result, “Some parents choose to keep their children home, and children injured or traumatized by strikes have dropped out of school.”

“As a teacher, my job is to educate. But how do I teach something like this? How do I explain what I myself do not understand?” asked Rehman, bringing his translator to tears. “How can I in good faith reassure the children that the drone will not come back and kill them, too, if I do not understand why it killed my mother and injured my children?”

“In the end I would just like to ask the American public to treat us as equals. Make sure that your government gives us the same status of a human with basic rights as they do to their own citizens,” said Rehman. “This indiscriminate killing has to end, and justice must be delivered to those who have suffered at the hands of the unjust.”

Rafiq, Zubair and Nabila stood bravely before the US Empire and demanded peace. Let’s hope that America listens.

Rania Khalek is an independent journalist living in the Washington, DC, area. She describes herself as a vegan, atheist and feminist troublemaker with a passion for social justice and independent media. Her work has appeared in AlterNet, Truthout, CommonDreams and In These Times Magazine. She’s also been a guest on FAIR’s Counterspin, the Ian Masters program, The Alyona Show and TruthDig Radio.

Copyright Rania Khalek, Truthout, 2013