Venezuela’s Rightwingers Are No ‘Beleaguered Democrats’

A study of five instances the right-wing opposition have been anti-democratic in Venezuela shows their real nature, writes Susan Grey

Venezuela’s right-wing opposition groups are often portrayed in parts of the international media as defenders of democracy, but nothing could be further from the truth.

Since Hugo Chavez was first elected president in 1998, right-wing groups have used every method imaginable to undermine and destabilise the country’s elected presidents, first Chavez and then Nicolas Maduro.

Chavez’s first few years of office saw the introduction of wide-ranging reforms designed to tackle poverty and inequality, meaning Venezuela’s resources were used to benefit the majority instead of the wealthy elite.

However, Chavez’s reforms made enemies among the old elite. They disliked his land reforms and his plans to halt the privatisation of the oil industry and they feared his mobilisation of the poor.

Almost immediately the right-wing opposition began their relentless, undemocratic and often violent attacks on the government and its allies, which continue until this day.

Perhaps the most well-known example of their anti-democratic actions was the April 2002 coup d’etat which temporarily removed Chavez, when an alliance of sections of Venezuela’s corrupt old ruling elite — including industrialists and businessmen, media owners and conservative military officers, with the support of the US government — conspired to overthrow Venezuela’s elected government.

The leaders of the coup refused Chavez’s offer to negotiate and engineered his arrest, falsely claiming that he had resigned the presidency.

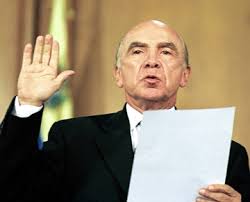

Pedro Carmona (Source: umbvrei.blogspot.com)

They installed a new president — Pedro Carmona — who immediately decreed the abolition of democratic institutions such as the National Assembly and granted himself the right to select and remove governors and mayors.

Another decree suspended a series of popular laws passed by Chavez.

But, as crowds demonstrated in support of Chavez, word reached the generals in the President’s Guard that no resignation had taken place and that the attempted change of government was unconstitutional.

Chavez was then released and democracy restored.

During the two-day coup over 60 “Chavistas” were killed in Venezuela, but the coup’s defeat didn’t deter Venezuela’s right-wing opposition from carrying on with their unconstitutional attempts to oust Chavez.

Later in 2002 and into 2003, Venezuela’s oil industry was paralysed by management lockouts, resulting in billions of dollars of lost revenue, with catastrophic effects on the government’s social investment programmes.

Shortages of petrol for transport led to a wave of shortages of essential goods.

The lockout was initiated by various right-wing groups calling for a “national strike,” including managers within the oil industry and the Venezuelan Chamber of Commerce.

Once again the aim of the lockout was to create enough chaos and hardship to force Chavez to resign. But again the right wing was defeated.

The lockout ended after 63 days, with workers loyal to the government managing to restart production.

While the right wing continued their anti-democratic antics — and to receive large amounts of funding from the US — throughout the rest of Chavez’s presidency, it was with his tragic death in 2013 that they again a saw chance to overturn social progress, and have stepped up their efforts to this end since.

After Chavez’s successor Nicolas Maduro’s victory in the 2013 presidential elections, losing candidate Henrique Capriles refused to accept the results and called his supporters onto the streets to “vent their anger.”

Thousands of right-wing protesters took to the streets and attacked the homes of prominent politicians and the head of the electoral council.

Health clinics and other social services built by the government also came under attack.

Capriles’s supporters set fires in the streets and marched through Caracas demanding a recount.

Eleven government supporters died in the violence. Opposition leaders insisted on a full recount, as well as the usual 46 per cent audit, despite the excellent reputation of the Venezuelan electronic voting system.

The Electoral Council agreed a full audit of the paper records and fingerprint registry, which confirmed Maduro’s victory.

Then in 2014, following an inflammatory speech by right-wing opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez, anti-democratic sections of the opposition took to the street in violent protest, demanding La Salida (“the ousting”) of Maduro.

Barricades in the roads, known as “guarimbas,” were constructed with burning tyres, rubbish and barbed wire, whilst protesters attacked anyone who appeared to be a government supporter.

Motor cyclists were killed by barbed wire stretched across the roads. Universities were ransacked, health clinics were set on fire, bus stations wrecked and food delivery vehicles attacked.

The death toll, including members of the public from all sides as well as police and security forces, reached 43 before the violence subsided.

Now, again, this year, antidemocratic elements of Venezuela’s right-wing opposition have again sought to force the removal of Venezuela’s elected president, no doubt encouraged by increasingly hostile statements from the US Trump administration towards Maduro’s government, with leading right-wing opposition figures openly encouraging sections of the military to oust the government.

As part of this we have seen a new wave of right-wing opposition violence, as exemplified by a recent armed attack from a stolen helicopter on the Supreme Court and Ministry of Justice.

Some of the worst (but by no means all) examples have seen protesters topple the main gate of a commune for low-income citizens, firing guns at residents, burning several homes and mortally wounding a child.

Other deaths have occurred in street violence, roadblocks, fire-setting and attacks on police officers trying to keep order.

Again this week, President Maduro has called for dialogue to find a peaceful way forward for the country to solve its difficulties but these calls have been rejected by much of the right-wing opposition, many of whom are hoping for a military coup or external intervention to remove Maduro before his term ends.

Progressives internationally shouldn’t be taken in by those seeking to portray Venezuela’s antidemocratic, right-wing opposition as beleaguered democrats, and should support dialogue and self-determination as the peaceful way forward for Venezuela to meet the challenges it currently faces.

Susan Grey is a member of the Venezuela Solidarity Campaign executive committee — you can join up at www.venezuelasolidarity.co.uk/join

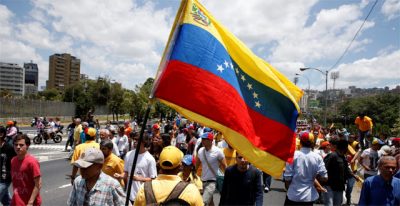

Featured image from Land Destroyer Report