Using Arable Land for Bio-fuels: Carbon Credits in the ‘Valley of Death’

The ugly effects of U.N.-backed ‘clean development’ in Honduras.

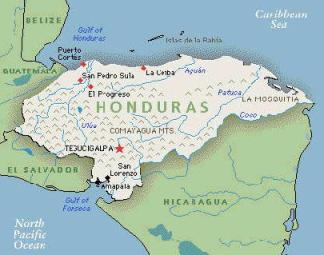

A boy stands next to a hut on a palm plantation in the Aguan Valley in August. The slogan reads “Area recovered by the MUCA,” which stands for “United Peasant Movement of Aguan.” (Photo by Orlando Sierra/AFP/Getty Images)

AGUAN VALLEY, HONDURAS– At 3,000 square miles, the Aguan River Valley in northeastern Honduras is about the same size as California’s Death Valley. But despite being green and fertile, the Aguan basin is becoming famous as a “valley of death.” Since January 2010, at least 45 displaced peasants have been killed in clashes over land rights in Aguan, and “the actual number of killings is probably much higher,” according to Annie Bird, co-director of the human rights advocacy group Rights Action (RA), who visited Honduras in September.

Bird and other critics say that the violence in Aguan is driven by competition over resources between local farmers and large-scale, biofuel production facilities. The valley is home to more than a dozen African palm plantations that supply “green” energy to Europe and Asia, as well as a pair of biogas plants that operate as part of a United Nations carbon-credit initiative.

“The agribusinesses are after all the prime farmland in Aguan,” Bird says. “That’s what’s driving the conflict here.”

African palm plantations have also been linked to land-based violence in Indonesia, Africa, and elsewhere in Latin America, as worldwide demand for biofuels has soared in recent years. But using arable land for fuels, as opposed to food production, has caused a spike in global food prices. In October 2011, the U.N. Committee on Food Security issued a report citing biofuel production as one of the leading causes of food shortages worldwide.

Ignoring its own committee’s report, the U.N. continues to endorse the two biogas plants attached to African palm plantations in the Aguan Valley as part of its controversial Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) program. A product of the Kyoto Protocol, CDMs allow governments and companies from Western countries to trade carbon credits with businesses in developing nations that utilize renewable energy and other carbon-saving techniques. Critics of the CDM program point to the food-vs-fuel dilemma, as well as the issue of “additionality”–that is, whether or not a given CDM would exist without U.N.-sanctioned investments. But Bird says there is a moral component as well.

“By approving investment in these projects, the U.N. has made itself an accomplice to a human rights crisis,” Bird says. “It’s just shameful.”

Killings and forced evictions

Both the CDMs in Aguan use the bacteria-rich wastewater left over from palm-oil extraction to produce methane for biogas. But the methane capture process is only cost-effective on a large scale–and observers say that gives local companies a direct incentive to expand operations.

David Calix, spokesman for the Campesino Movement of Aguan (MCA), says, “Within the last two years more than 1,500 peasant families have lost their homes, schools and communities due to forceful evictions,” all of which have been linked to African Palm expansion efforts in the Aguan valley.

In July, the International Federation of Human Rights (FIDH) released a report on Aguan alleging evictions and armed attacks against local communities by “plantation security guards and private militia groups” allowed to act with impunity. The FIDH paper forced a couple of powerful European investors to back out of the Aguan CDM project and caused the European Parliament to order a fact-finding mission. So far, however, these measures don’t seem to have had any impact on the escalating violence.

Over just two days in August, skirmishes between guards and peasants left 11 people dead. A few days later, two more campesino leaders were assassinated–one of them, Pedro Salgado, was shot down in his home along with his wife. An entire peasant village was burned to the ground. The international outcry became so severe that in early September, the Honduran government dispatched a force of about 1,000 special police officers and soldiers to occupy the valley.

But Bird says that instead of protecting peasants’ human rights, the occupation forces have aided in their persecution. Reports have emerged of police and soldiers cracking down on peasant communities, and even taking part in evictions. “Death squad” attacks on peasants have continued at about the same pace during the occupation, with four assassinations in the same week in early October. No arrests have been made in any of the killings, and no suspects have been named.

Hazardous occupation

“The troops say they have come to bring us security, but that is a lie,” says MCA President Rodolfo Cruz. “They are here to serve the interests of the rich land owners, the same ones who control the politicians back in [the Honduran capital of] Tegucigalpa.” Cruz is also acting mayor of a small peasant community called Rigores, which he claims has been threatened several times with eviction by both security guards and law enforcement.

Cruz also reports that citizens are being searched at random, and that there have been mass round-ups and arrests as the authorities hunt down leaders of the movement.

“They are accusing us of having weapons, of forming an insurgency,” says Cruz, whose 16-year-old son, Santos, was allegedly tortured for information while in police custody on September 19. Cruz maintains that the MCA and other organizations are pacifist movements dedicated to nonviolent resistance.

Bird, who has researched the case, believes there is no doubt that Cruz’ son was targeted by authorities because his father is a prominent spokesman for land reform. “It’s all part of their pattern of intimidation,” she says. “There is no functional justice system in Honduras.” As further evidence of legal dysfunction, Bird points out that the businessman with the most holdings in Aguan, Miguel Facusse Barjum, was recently revealed by WikiLeaks to have strong ties to Colombian cocaine traffickers. “The police are evicting peasants from the property of a known drug lord,” she says. “That just shows you how rotten the system is.”

Although in September there were hints in the Honduran press that the police have captured cell phones that prove the existence of a rebel army some 300 strong, Honduran Police Chief Julio Benitez is much more circumspect. “We really don’t know what is going on in Aguan,” Avila says. “We know there are armed groups. We know people are being shot up under mysterious circumstances. But it is very complicated.”

When asked about the charges of police brutality, Avila declined to respond, saying only, “[The Honduran police] are a professional organization. We behave in a professional manner. We are working hard to safeguard the peasants of Aguan and to protect them from violent criminals.”

Push for reform

“The situation in Honduras is, of course, of great concern to us,” CDM board Chair Martin Hession says. “We don’t want to be associated with this type of thing in any way.” Hession says that as a result of the violence in Aguan, the CDM Board has “increased surveillance” in regard to approving new projects.

But Eva Filzmoser, program director of the Brussels-based CDM Watch, believes that’s too little, too late. “We are deeply disappointed … that the [Aguan] project was registered despite the serious concerns about alleged human rights abuses,” Filzmoser wrote in an e-mail.

Filzmoser charges that Hession and the rest of the board chose to ignore early reports of violence coming out of Honduras when they approved the project in July of 2011. Part of the problem is systemic, she writes, stemming from a lack of stakeholder oversight by the CDM board itself. “The [Aguan] project would never have been registered if the proper rules were in place,” Filzmoser wrote.

Bird also sees an inherent flaw in the CDM program. “If you’re taking away land from poor people to generate biofuels, you’re effectively condemning them to death by starvation,” she says.

Hession says such things are beyond the purview of the CDM board. “We can’t be the arbiter of human rights across the world.” To which Bird responds: “That’s the single, fundamental mandate of the U.N. Human rights are what the U.N. was created to promote. And the CDM board is still part of the U.N.”

For Cruz, who is also a farmer, the issue at stake is less philosophical than practical: “All we want is a place to grow our corn, to grow our beans,” he says. “All we want is a right to work the land.”

Jeremy Kryt is a graduate of the Indiana University School of Journalism and the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He has been reporting from Honduras since August 2009, and his coverage of the crisis there has appeared, or is forthcoming, in The Earth Island Journal, Huffington Post, Alternet and The Narco News Bulletin, among other publications.