US Firestorming of Tokyo Rivaled the Hiroshima Bombing

At the outbreak of war, Roosevelt had strongly condemned the killing of civilians from the air.

Featured image: Charred remains of Japanese civilians after the firebombing of Tokyo on the night of 9–10 March 1945. (Source: Ishikawa Kōyō / Wikimedia Commons)

In the early hours of 10 March 1945, as America’s heavy aircraft dropped over 1,600 tons of bombs on Tokyo, a firestorm larger and hotter than ever before was brewing. During the firebombings of Dresden and Hamburg, temperatures reached 1,500 degrees Fahrenheit, but in Tokyo it soared to a blinding 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit.

Such was the heat unleashed by US bombers over the Japanese capital, that civilians in their air raid shelters were beginning to suffocate. Rather than be overwhelmed, they fled into the streets, becoming glued to the melting asphalt under their feet. Those now stuck in the roads or pavements were helpless, many of whom were heavily charred by the rapidly growing fires.

Like Venice, the famous northern Italy city, Tokyo is dissected with canals. The people who avoided being rooted to the asphalt in the open, jumped into the many canals, among them numerous women and children. Due to the unprecedented temperatures the canals, particularly the smaller ones, started to boil, cooking to the death further thousands of civilians.

About 280 American B-29 Superfortresses – four-engine heavy bombers – had ignited this unparalleled firestorm. Exiting the scene of destruction, many of the aircraft crews had to quickly attach their oxygen masks; it prevented them from vomiting or passing out, such was the stench of death emanating from about five thousand feet below.

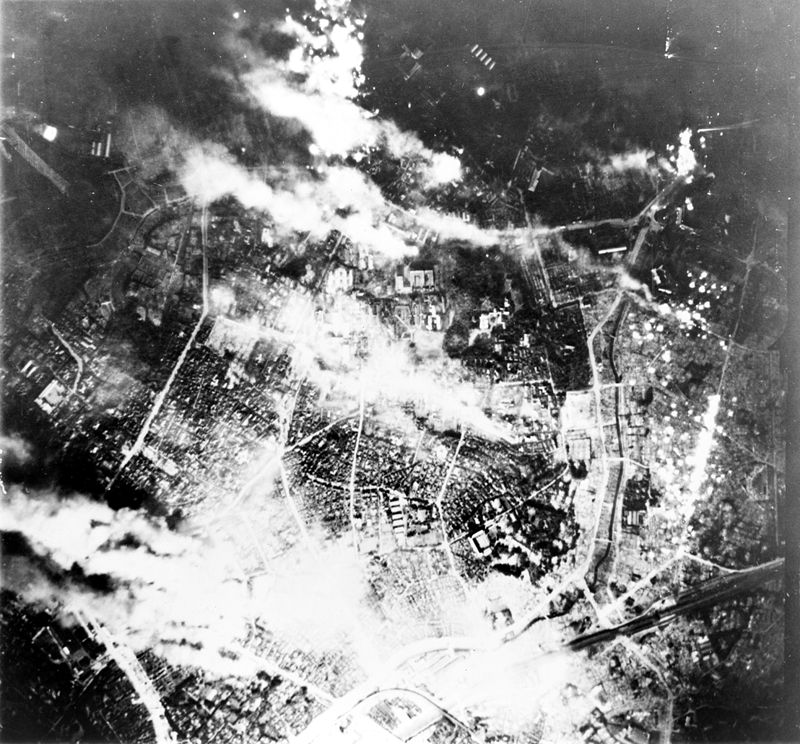

“Tokyo burns under B-29 firebomb assault.” May 26, 1945. (Source: US Army Air Forces / Wikimedia Commons)

US Major General Curtis LeMay had ordered the firebombing of Tokyo, with maximum casualties in mind, living up to his nickname “Bombs away LeMay”. In a June 1981 interview with the American historian Michael Sherry, LeMay said:

“There are no innocent civilians. It is their government and you are fighting a people, you are not trying to fight an armed force anymore. So it doesn’t bother me so much to be killing the innocent bystanders”.

In 1945 Roger Fisher, a First Lieutenant and future Harvard Law professor, was LeMay’s “weather officer” on the island of Guam, in the western Pacific Ocean. Just before the Tokyo firebombing, Fisher revealed that LeMay “asked me a question I’d never heard before”. What LeMay wanted to know was, “How strong are the winds going to be at ground level?” Fisher could not know, informing LeMay that winds can only be predicted (in 1945) “at high altitudes, with reconnaissance flights” and “at intermediate altitudes if we dropped balloons”. LeMay than asked

“How strong does the wind have to be so that people can’t get away from the flames? Will the wind be strong enough for that?”

Fisher stammered and was unable to answer, quickly retiring to his quarters, and saying of LeMay that,

“I didn’t go near him again that night. I had my deputy deal with him. It was the first time it had entered my head that the purpose of our operation was to kill as many people as possible”.

The ground conditions were, as it turned out, exactly to LeMay’s liking, with prevailing winds of up to 28 mph (45 km/h). The blustery weather was akin to a bellows fanning the fires, further aided by the dry atmosphere and Tokyo’s extensive wood-and-paper buildings.

Officially, around 100,000 civilians were said to have died as a result of the bombing raids, which lasted a mere couple of hours. However, noted historians such as Gabriel Kolko, an American-born Canadian academic, estimates the Tokyo body count at 125,000 – which rivals the final death toll from the Hiroshima bombing.

The Tokyo firestorming, code-named “Operation Meetinghouse”, was the single deadliest air raid of World War II by quite some distance. In addition, around one million of Tokyo’s residents suffered injury during the attack, while one million were also left homeless. Over 250,000 of the city’s buildings were destroyed, a quarter of all structures in Tokyo at the time, one of the world’s largest cities. Indeed, the size of the area destroyed (almost 16 square miles) was larger than the destruction wrought by both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings.

Many of the American aircraft that inflicted the devastation, upon return to their base in the Mariana Islands, were found to be streaked with ashes from Tokyo’s buildings. The Japanese anti-aircraft defenses proved especially inadequate, shooting down only 14 American planes. LeMay was satisfied with the results. After the war he acknowledged that,

“Killing Japanese didn’t bother me very much at that time… I suppose if I had lost the war, I would have been tried as a war criminal… Every soldier thinks something of the moral aspects of what he is doing. But all war is immoral and if you let that bother you, you’re not a good soldier”.

Had LeMay been on the German or Japanese side, there is a great probability he would have been tried as a war criminal – along with others, such as his British counterpart Arthur “Bomber” Harris. The brutal air assaults ordered by both LeMay and Harris made those of the Luftwaffe chief, Hermann Goering, appear puny by comparison. After conflict ends, it seems only the defeated are held to account for their crimes. In the months following the war two military tribunals were held, the Nuremberg Trials and Tokyo Trials. There was no clamoring call for similar proceedings to be held in Washington or London.

On 1 September 1939, the day the Nazis invaded Poland, US president Franklin D. Roosevelt made an appeal:

“The ruthless bombing from the air of civilians in unfortified centers of population… has sickened the hearts of civilized men and women and has profoundly shocked the conscience of humanity… under no circumstances undertake the bombardment from the air of civilian populations, or of unfortified cities”.

Roosevelt was referring to the Japanese bombing of Shanghai in 1937 – and also the German and Italian bombardment of the Basque and Catalonian cities of Guernica, Barcelona and Granollers, during the Spanish Civil War.

Roosevelt’s words would prove hollow. Less than four years after his address, the American Eight Air Force combined with the Royal Air Force in firebombing Hamburg, Germany’s second largest city. The outright targeting of civilians over Hamburg, lasting just over a week in July 1943, killed over 40,000 people – slightly more than those that died during the Luftwaffe’s eight month blitz of Britain, ending in May 1941. Roosevelt was still in office when large sections of Tokyo were being burned to a cinder, along with great numbers of its civilians. On these occasions, there were no objectives put forth by Roosevelt regarding “the ruthless bombing from the air of civilians”.

Indeed, it was Roosevelt who was a key figure in the formulation of the atomic bomb. He oversaw its continuing development until his death on 12 April 1945, even after it had long become clear to the Allies that Hitler had no nuclear program. Roosevelt had previously said the reason to produce the atomic bomb “was to see that the Nazis don’t blow us up”. Yet, by 1944, this logic was no longer valid, as Roosevelt surely knew.

Hitler had shunned nuclear research for a variety of reasons, on both racial and pragmatic grounds, also foreseeing that these weapons “would force humanity down the road to extinction”. This earth-shattering concern was not expressed by Roosevelt, successor Harry Truman or Winston Churchill. As a result, the shadow of nuclear weapons hovers over humanity to this day.

Meanwhile, in February 1942, Churchill had himself green-lighted the first strategic bombing of urban centers in the war – with the real aim of killing and terrorizing Germany’s civilian population. A British Air Staff directive, dated February 14 1942, outlined that the air war “should now be focused on the morale of the enemy’s civil population”.

Also in February 1942, Britain had launched the famous Avro Lancaster heavy bomber, hundreds of which participated in the murderous firestorming of Hamburg the following year. Already, by 1940 and 1941, the RAF had introduced two other four-engine heavy bombers, the Handley Page Halifax and the Short Stirling – both of which were involved in the “first ever 1,000 bomber raid” over Cologne, in the early hours of 31 May 1942. Almost 1,500 tons of bombs were dropped on Cologne, a city of significant size in western Germany.

The Luftwaffe possessed not a single four-engine bomber aircraft. That is, planes capable of flying extended distances, with large payloads of explosives, thereby inflicting significant damage. The Germans only had two-engine medium and short range bombers. Hitler was not a proponent of strategic bombing and targeting of urban populations en masse, nor had he prepared for it. He only switched focus after the RAF inflicted serious damage upon the medieval city of Lubeck, in late March 1942. Just over a fortnight later, 14 April, Hitler relayed an order declaring that the German air war “be given a more aggressive stamp”, focusing on areas “where attacks are likely to have the greatest possible effect on civilian life”. When it came to terror bombing of civilians, it was something of a British and American specialty.

The German Blitz itself – which began on 7 September 1940 – was Hitler’s direct response to a series of British attacks on Berlin over the previous fortnight. The German capital was bombed for the first time in the early hours of 25 August 1940, a sure sign of things to come. The bombings were a result of Churchill’s increasingly belligerent war strategy.

*

Shane Quinn obtained an honors journalism degree. He is interested in writing primarily on foreign affairs, having been inspired by authors like Noam Chomsky. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.