Unrigging the System of “Money in Politics”: Harvard’s Lawrence Lessig for US President?

“A democracy cannot function effectively when its constituent members believe laws are being bought and sold.”

Justice John Paul Stevens, Citizens United v Federal Election Commission, 558 US 310 (2010).

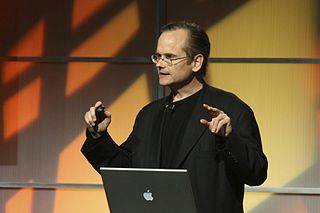

There have been stranger suggestions, though this one does come close. Last Tuesday, the known authority on campaign finance reform Lawrence Lessig of Harvard University launched a committee to explore the options for commencing a campaign for a “referendum president” of which Jimmy Wales is its president.

The vast majority of Americans believe their government has been captured. If there was a referendum to end that corruption, it’s clear that America would vote overwhelmingly to support it. But the American constitution doesn’t give the people the power of a referendum. So Lessig has a plan to hack one instead. [1]

The target is the raising of sufficient funds by Labor Day (September 7) to enable Lessig to run in the 2016 Democratic Primaries. If the money is not raised, the charged committee will return it except in cases when the contribution is non-contingent. In any case, even if Lessig is elected, he promises to quit. Take the crown, in short, and discard it. An interesting development indeed.

As Lessig explained in the Daily Beast,

“My candidacy would be a referendum. Elected with a single mandate to end this corrupt system, I would serve as long as it takes to pass fundamental reform. I would then resign and the vice president would become president.”[2]

The structural nature of the campaign is what stands out. This is largely because the US electoral system, sluiced with cash, mediates and determines candidates in advance, weaning the less-moneyed while privileging plutocrats. The system thereby acts as its own, self-sorting sieve, replete with calculating lobbies and vested interests.

Lessig’s hobby horse remains campaign finance reform, something made seemingly impossible after the Supreme Court upended matters in Citizens United v Federal Election Commission 558 US 310 (2010). The First Amendment was cited, in rather novel fashion, to bar government regulations prohibiting independent expenditures by corporations and unions. Associations of individuals in addition to individual speakers were also held to be covered by the amendment.

Free speech and the imperative of the wallet became indivisible – to disseminate speech, one needs to expend money. A disgruntled Justice Stevens, in dissent, would warn that the decision “threatens to undermine the integrity of elected institutions across the Nation.” It rejected “the common sense of the American people, who have recognised a need to prevent corporations from undermining self-government since the founding, and who have fought against the distinctive corrupting potential of corporate electioneering since the days of Theodore Roosevelt.”

In Lessig’s political vision, there are no suppurating super PACs with engorged wallets, of which the 2016 campaign is already rife with. But more to the point, Lessig’s argument is that such contrarians as Bernie Sanders, while they speak against the corrupting hue of money in politics, do not necessarily have a line of attack on that influence. “You’re talking about a string of reforms that simply cannot happen in the Washington of today. The ‘system is rigged’.”

Change cannot be a matter of simply influencing a few individuals on the Hill, and tidying a few corners in the Capitol. If one does not un-rig the system, “collective amnesia” will take its usual quarry. Reform will simply be another empty word among an entire collection of vacuous phrases.What of a Citizen’s Equality Act limiting donations from billionaires? That could be something else, though it has been deemed “in the modern money-flush electoral landscape… the equivalent of political suicide.”[3] As Lessig’s site outlining the Act explains, reform is to happen in three seminal areas.[4] The first is the equal right to vote, a “meaningfully equal freedom to vote”. This would entail the enactment of the Voting Rights Advancement Act of 2015 and the Voter Empowerment Act of 2015.

Then comes the hallowed principle of equal representation. Lessig takes the lead on this from the FairVote plan as the most “comprehensive”, entailing the drawing up of districts and structuring of election systems that would “give each citizen as close to equal political influence as possible.” The object here is ending rampant gerrymandering with a Ranked Choice Voting system.

The last of the three principles centres on ending one of the core causes of corruption in the US political system, notably “the concentration of funders of political campaigns.” At the lowest threshold, there should be a hybrid of John Sarbanes’ Government by the People Act and Represent.US’s “American Anti-Corruption Act.” This would incorporate a voucher system, allowing each voter the means to contribute to congressional and presidential campaigns. Matching funds would be provided for small-dollar contributions. And limits would be introduced on breaking the links between those in government employ and the lobby sector.

All of these proposals would only seem obscene to those who have deemed the condition of US congressional and presidential elections inalienably linked to capital. Those with capital magnify their influence via their political servants. The business civilization has its own rankings, its own sense of whether to allocate preferences, or withdraw them. There is no market place for ideas, so much as a market place for politicians.

Lessig will have none of that, and nor should citizens. As with so many seemingly radical projects, Lessig’s near religious mania harks back to a certain purity of voting equality, an attempt to cleanse a corrupt, pockmarked body. Those happy with the muddied state of things will be ganging up to stop him, and remind him of a previous effort when he vainly attempted to form his own super PAC and lost $10 million.

This is something of a different order, reminding the electorate, as Justice Stevens did in Nixon v Shrink Missouri Government PAC (2000), that, while money is property, speech is not. Ideas, rather than the secondary means of implementing them, are what counts in terms of protection.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email:[email protected]

Notes

[1] https://medium.com/@JimmyWales/let-s-light-up-the-internet-1337441393a4

[2] http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/08/13/i-m-running-for-president-to-quit.html

[3] http://www.psmag.com/politics-and-law/run-lawrence-run

[4] https://lessigforpresident.com/the-act/