U.S. “Special Plans”: A History of Deception and Perception Management

A major controversy during the administration of President George W. Bush concerned the use or misuse of intelligence with regard to Iraqi weapons of mass destruction programs and possible links between Iraq and al-Qaida. The best known elements of that controversy were Iraqi motivations behind the procurement of aluminum tubes, whether Iraq had sought to acquire uranium from Niger, if Iraq was seeking to reconstitute its nuclear weapons program, and whether it was producing and stockpiling chemical or biological weapons.

But another aspect of that controversy involved two components of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy — the Office of Special Plans and the Policy Counterterrorism Evaluation Group (PCTEG). During the Bush administration, and after, there have been numerous accounts that either confused the functions of those offices or attributed actions to them that they never undertook.

Photo: Under Secretary of Defense Douglas Feith.

Photo: Under Secretary of Defense Douglas Feith.One potential cause for confusion is that the term “Special Plans” has been a euphemism for deception since World War II, and for ‘perception management’ (which included deception and ‘truth projection’) since at least the mid-1970s. And during the George W. Bush administration the term apparently had a dual use — as a traditional euphemism (for perception management) as well as a temporary title for planning with regard to Iraq, Iran, and counterterrorism.1

Clearing up the confusion requires an examination of four different classes of documents — those concerning deception and special plans prior to the Ronald Reagan administration, those focusing on special plans during the Reagan administration, those related to the Office of Special Plans under Under Secretary of Defense Douglas Feith, and others focusing on the PCTEG.

Deception & Special Plans, 1946-1980

As noted, the term Special Plans was used as a euphemism for deception going back to at least World War II. In March 1944, General Omar Bradley, commander of the U.S. 12th Army Group, established a Special Plans section to “prepare and implement deception and cover plans for all United States forces in the United Kingdom.” Post-war use of the term is illustrated by the existence, in December 1948, of the Special Plans Section of the Strategy Branch of Headquarters U.S. Air Force.2

Over two years earlier, in the summer of 1946, the absence of organizations to conduct cover and deception operations was the subject of several War Department memos. A Top Secret July 5, 1946 memo (Document 1)from the Office of the Chief of Staff assigned responsibility for the supervision of War Department cover and deception matters to the Director of Plans and Operations. Three days later, the department’s Adjutant General directed (Document 2) that the commanding general of the Army Ground Forces manage tactical deception activities — that is deception during battle, and those which might involve radio, sonic, or camouflage deception.

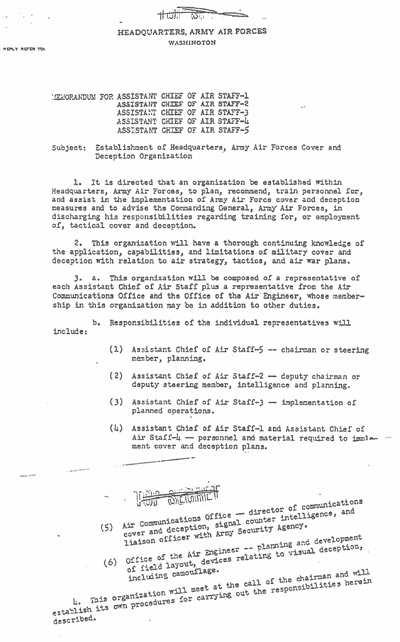

Two further memos from the same period of time addressed the issue of establishing a cover and deception organization for the Army Air Forces (AAF). A memo (Document 3) from the assistant chief of the air staff for intelligence notes the role of cover and deception in World War II, the absence of an organization to conduct such activities, and the need to establish one. He also suggests roles that the assorted AAF assistant chiefs might play in cover and deception operations. Another memo (Document 4) directed creation of an AAF cover and deception organization — although it is not clear what further action, if any, was taken.

A document from three decades later, a Secret September 28, 1976, memo (Document 5) from the director of naval intelligence to the acting chairman of the “United States Evaluation Board,” indicates that the board was involved in managing deception operations. The main subject of the memo was whether information requested by the board was “within the purview of the USEB.” Other parts of the memo note that the board was established for cover and deception purposes and that one of its roles was processing “feed material” — information or documents — to be transmitted to target nations via controlled foreign agents (CFAs) or double agents (DAs).

In August 1980 the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) entry (Document 13) in the Department of Defense telephone directory indicated the existence of a Special Plans Branch within the Joint Staff’s Special Operation Division. A page from the 1980 JCS organization and functions manual (Document 6) indicated that the term “Special Plans” was equivalent to “perception management,” while not explaining that perception management consisted of two distinct and opposite activities — deception and ‘truth projection.’ Not surprisingly, consideration of various attempts at perception management were viewed as part of the U.S. response to the seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and its employees in November 1979.3

Examples of work concerning perception management with regard to Iran include a number of declassified memos or reports produced in 1980. One of those memos, “Perception Management: Iran” (Document 7), after stating its purpose and providing background, specifies its assumptions (e.g. “the principal decision makers who can authorize release of US citizens held in Iran are the Ayotallah Khomeini and/or the terrorists holding the prisoners”) and then goes on to specify 12 possible means of perception management. Those means included radio broadcasts using U.S.-owned transmitters, intrusion into Iranian radio communications frequencies, letter-writing campaigns, and the demonstration of military capabilities.

A more detailed product relating to the hostages (Document 8A, Document 8B), which emanated from the Army’s 4th Psychological Operations Group, examined the target audience and stated themes, assessed effectiveness, examined accessibility, and offered conclusions. Those conclusions asserted that the “most lucrative target audience” were Khomeini loyalists and other religious devotees. The most productive themes with respect to Khomeini and his followers would be those “emphasizing dangers posed to the Islamic revolution by prolongation of the embassy crisis.”

Work on perception management with regard to Iran also included production of a series of background option papers, including one (Document 10) on “interim non-violent options.” Those options included starting a rumor campaign that some hostages had been killed or kidnapped (as prelude to calling for accountability by the “IRC” — presumably the Iranian Revolutionary Council), dropping leaflets stating the case for release of hostages and restatement of U.S. military capability, interdiction of the Tehran power grid, probes of Iranian air space, and an overflight of Iran using the supersonic SR-71. The overflight might include “detonation of photo flash over selected Iranian military, government, and Industrial facilities.”

A June 1980 paper (Document 12) discussed possible psychological operations in support of Project SNOWBIRD — the planning and preparation by a joint task force for a second mission to rescue the U.S. hostages in Tehran. Included among the possible operations were deceptive “small actions and communications” to suggest that the United States was beginning to have second thoughts about employing military force. In addition, the memo stated that some of the proposed actions “are on very tenuous legal ground.”

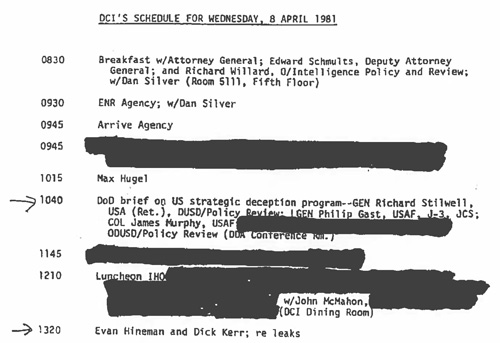

Central Intelligence Agency, “DCI’s Schedule for Wednesday, 8 April 1981.” From Document 14.

Special Plans & Deception, 1981-1990

The DoD telephone directory and JCS organization and functions manual from 1980 provided documentary evidence that by the end of the administration of Jimmy Carter special plans was considered of sufficient importance to have a component of the Joint Staff dedicated to that activity. (According to one former officer in that division, a special plans branch had existed for several years when he joined the division in 1978.)

But the interest in strategic deception and special plans would be raised to another level in the administration of Carter’s successor, Ronald Reagan. One element of that concern was what the Soviet Union was doing to deceive or hide from U.S. intelligence — a concern that led to support for at least two satellite programs, a radar imagery program (LACROSSE) and a stealth imagery satellite (MISTY).4

Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) William J. Casey.

Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) William J. Casey.

Very early in the Reagan administration, Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) William J. Casey was briefed on the “US strategic deception program” (Document 14). Among those briefing Casey were General Richard Stilwell, the deputy under secretary of defense for policy review, and Lt. Gen. Philip Gast, the director of operations for the Joint Staff. Possibly it was another briefing on the same subject later that month to acting CIA deputy director of operations John Stein, that led Stein to write Casey (Document 15) reporting that he had told Stilwell and General Eugene Tighe, director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, that he believed “the project worthwhile and long needed” and that he “offered to them full support from the directorate.”

A year later, in April 1982, Stein, who by then had had the ‘acting’ removed from his title, received a letter (Document 16) from Major General E.R. Thompson, former Army assistant chief of staff for intelligence. The letter indicated that Thompson was director of the Defense Special Plans Office (DSPO), and informed Stein that attached to the letter he would find the DSPO charter as well as an Operational Capabilities Tasking memorandum that Thompson had received from the DIA director. Beyond noting the enclosures, the letter informed Stein that the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence had reduced the office’s budget request to 20 persons and $1.6 million, which “will allow us to stay in business, but only in a planning mode.” Even worse for the future of the office, the House intelligence oversight committee had “zeroed out the request for FY 83” — which Thompson attributed to the lack of a charter at the time and concern about the extent of CIA support for the effort. He also noted that the DCI would be receiving an appeal to support the SSCI recommendation at the Congressional authorization committee’s conference.

Photo right: General Richard G. Stilwell.

Photo right: General Richard G. Stilwell.But whatever efforts the DoD and CIA made to ensure that DSPO continued in operation failed and failed fairly quickly — as indicated by the DoD’s response (Document 18) to a June 1983 Freedom of Information Act request for copies of “the organization chart and mission statement for the Defense Special Plans Office.” A letter from Charles Hinkle, the DoD’s director for Freedom of Information and Security Review, stated that “no record pertaining to [the] request was found and that ‘no such office’ exists.” He did attach a memorandum from DSPO sponsor Richard Stilwell to the director of the Washington Headquarters Service (WHS), which explained why there was “no such office.” It indicated that the DSPO charter had been the subject of two DoD Directives — one classified Confidential and the other classified Top Secret. Stilwell informed the WHS director that “the directives were charter documents establishing a DoD activity whose establishment subsequently was not authorized by Congress.” Stilwell recommended that “holders destroy them immediately.”

A second FOIA response (Document 19), received that fall by Scott Armstrong, then of theWashington Post, provided a bit of additional information about the sensitivity with which DoD viewed information about the office. Armstrong had submitted requests for records relating to the DSPO. Hinkle’s response stated that all relevant DoD documents relating to the office were classified. He also attached the same memo from Stilwell recommending that holders of the directives destroy them — as well as a somewhat more forceful cancellation notice from O.J. Williford, whose title was given as “Director, Correspondence and Directives.” Williford instructed, rather than recommended, with regard to the two DoD directives on DSPO, that receivers of the notice to “remove and destroy immediately all copies you have on file.”

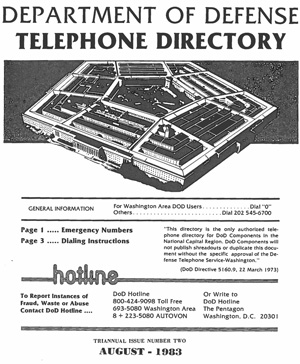

Department of Defense Telephone Directory cover from document 20.

Department of Defense Telephone Directory cover from document 20.

While DSPO did not survive into the winter of 1983, other Special Plans organizations in the Department of Defense continued to function. The department’s December 1983 telephone directory (Document 20) showed that, in addition to the previously noted Special Plans Branch in the Joint Staff Special Operations Division, there was a Special Plans Branch within the Human Resources Division of the Defense Intelligence Agency. Also telling is the fact that the two offices were located side-by-side in the Pentagon — in 2C840 (JCS) and 2C841 (DIA).5

Documents also allude to some of the product of the special plans effort in the Joint Staff — although in highly redacted form. In August 1985, the Joint Staff J-3 produced a Top Secret Report* by the J-3 to the Joint Chiefs of Staff on Special Plans Overview Guidance (Document 21). The only unredacted substantive portions from the original DoD FOIA response were several section titles indicating some of the objectives of possible perception management efforts, including “deterrence of US/Soviet Hostilities,” “crisis stability,”and “advantage in warfighting capability.” A recent request for a less-redacted copy of the document produced a ‘no records’ response.

The following year, press reports suggested two possible deception/perception management efforts by the United States. In October 1986, a front-page story in the Washington Post, written by Bob Woodward, stated that “in August the Reagan administration launched a secret and unusual campaign of deception designed to convince Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi that he was about to be attacked again by U.S. bombers and perhaps be ousted in a coup.” The objective was to increase Gadhafi’s anxiety about his internal strength and U.S. military power with the expectation that he would be less likely to undertake acts of terrorism and be more likely to be toppled from power. Several months earlier, in March, Aviation Week & Space Technology reported that the “Defense Dept., in conjunction with the Central Intelligence Agency, has initiated a disinformation program that it is applying to a number of its aircraft and weapons development programs to impede the transfer of accurate technological information to the Soviet Union.” The effort was reported to cover 15-20 programs, including the B-2 bomber, the Navy’s A-12 Avenger, aircraft being tested at Area 51, and the Strategic Defense Initiative.6

The topic of perception management with regard to strategic defense was the subject of an April 1987 memorandum (Document 23) from the Joint Staff director of operations to 20 different individuals, including the JCS chairman, military service chiefs of staff, the commanders of the unified commands, and the directors of the DIA and National Security Agency. Titled Special Plans Guidance – Strategic Defense, its few unredacted portions defined strategic defense as “all military matter and operations pertaining to the defense of the North American region, including activities involving Canada, against attack by aircraft, missiles, or space vehicles.” It also notes twelve broad areas which possibly warranted additional review when considering [term deleted but likely ‘perception management’] support of Strategic Defense.” Included among those areas were: surveillance and detection, recovery and reconstitution, hardening and survivability, and Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) resources.7

In 1994, the General Accounting Office (GAO) investigated whether a June 1984 Army ballistic missile defense test that had taken place after the establishment of SDI, had involved deception which may have suggested a more successful effort than had actually occurred. The GAO reported (Document 26) that there was a DoD deception program associated with the Homing Overlay Experiment — with the intention of affecting Soviet perceptions of U.S. ballistic missile defense capabilities and influencing arms negotiations and Soviet spending. However, the accounting office also reported that the secretary of defense said the planned deception (which would have involved the explosion of the target if the interceptor failed to hit it but passed sufficiently close to “support the appearance” of an interception) was cancelled prior to the test.

The Office of Special Plans, 2002 – 2003

Twenty years after the disestablishment of the nascent DSPO another special plans office would be at the center of controversy. This time it was the Office of Special Plans, established under Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Douglas Feith. In his memoir, War and Decision, Feith writes that in the summer of 2002, as “the President moved toward challenging Iraq in the United Nations, the Iraq-related workload in Policy became overwhelming.” The “Policy organization had only two staffers devoted full-time to Iraq,” but “this absurd situation was rectified with the creation of the team that became known as the Office of Special Plans.”8

Feith goes on to state that after he and William Luti, who headed the Near East and South Asia (NESA) office, had received permission to hire about an additional dozen people for that office, it became possible to create a distinct division in the office to handle northern Persian Gulf affairs. According to one account, the office was “given a nondescript name to purposely hide the fact that, although the administration was publicly emphasizing diplomacy at the United Nations, the Pentagon was actively engaged in war planning and postwar planning.”9

Feith, while agreeing on the desire to give the office an unrevealing name, explained the office’s title somewhat differently — “The President was emphasizing his desire for a diplomatic solution to the Iraq problem, but various journalists interpreted his intensified attention to Iraq as a sign that he had decided on war.” Bearing in mind a warning from Deputy National Security Adviser Stephen Hadley to administration officials “not to aggravate the problem” and since Feith and Luti “anticipated a flap” if the news media found out that the Pentagon had established a new Iraq office, they decided on an alternative designation for the new organization — Special Plans.10

Feith writes that “the Office of Special Plans was nothing more than a standard geographic office within the Policy organization, with the same kinds of responsibilities that every other geographic office in Policy had. It was simply the office of Northern Gulf Affairs — and indeed, after Saddam was overthrown, that became its name.” However, “although the name ‘Special Plans’ was intended to avert speculation, the two words eventually were taken by conspiracy theorists to imply deep and nefarious motives.”11

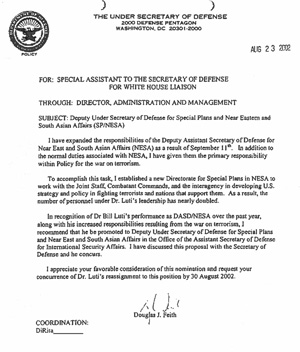

Douglas J. Feith, Undersecretary of Defense, For: Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for White House Liaison, Subject: Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Special Plans and Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs (SP/NESA), August 23, 2002. Unclassified. Document 27.

Douglas J. Feith, Undersecretary of Defense, For: Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for White House Liaison, Subject: Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Special Plans and Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs (SP/NESA), August 23, 2002. Unclassified. Document 27.

Released documentation on the creation and disestablishment of the Office of Special Plans begins with an August 23, 2002 memo (Document 27) from Feith to an assistant to the secretary of defense. In the memo Feith notes his expansion of the responsibilities of the deputy assistant secretary of defense for Near East and South Asian affairs “as a result of September 11th,” that he had established a “new Directorate for Special Plans in NESA,” and had requested that Luti be promoted to deputy under secretary of defense for special plans and Near East and South Asian affairs (within the Office of International Security Affairs). The deputy secretary of defense approved the request via a September 13, 2002 memo (Document 28), and a month later the department’s director of administration and management followed suit (Document 29). That approval covered both the creation of the new position and Luti’s reassignment to that position.

A description of Luti’s responsibilities were part of an undated document (Document 31) that ran a little over two single-spaced pages. The description, in accord with the desire to avoid press reaction, never specifies what was meant by the term ‘special plans,’ and notes the incumbent’s responsibility to support the department’s policy and ISA’s “in developing U.S. strategy for a wide-range of contingencies and assessing the adequacy of U.S. campaign planning to carry out the strategy.” It also noted the deputy under secretary’s role in planning and policy direction on ISA programs concerning all nations in the Middle East and South Asia.

Another undated document (Document 32), consisting of a cover page and three charts, provides a clearer description of the changes. The cover itself indicates that the Office of Special Plans was actually the Office of Special Plans and Near East and South Asia Affairs and its expansion was motivated by a need to “deal with Iran, Iraq, and War on Terrorism.” A chart shows that within the office was a “Director, Special Plans,” who was formerly the “Director, Northern Gulf.”

Products of the office include two briefing papers. One, focused on the pros and cons of a provisional government for Iraq (Document 29). Another (Document 34) concerned “Iraqi Opposition Strategy.” Among its key points were that “U.S.-led coalition forces will have the lead in liberated Iraq,” and that “Iraqis will initially have only an advisory role.” It noted disagreement with the State Department’s view that the external opposition should be treated differently from “newly-liberated Iraqis.”

In July 2003, as Feith noted, in the aftermath of the fall of the Saddam Hussein regime, the office’s name and its components were changed (Document 35). The term ‘special plans’ was removed and Luti’s title reverted to deputy under secretary of defense for Near Eastern and South Asian affairs while the director of special plans became the director for Northern Gulf affairs.

As Feith also observed, the office’s existence and purpose became the subject of numerous articles and papers – attention which continued during and after the office’s demise. Two of the earliest examples of that attention include a response from the department’s public affairs office (Document 33) to a series of questions from journalist Seymour Hersh — who was researching an article for The New Yorker that would be published in the May 12, 2003 issue under the title “Selective Intelligence” — and a June 4, 2003, Department of Defense press briefing (Document 35).12

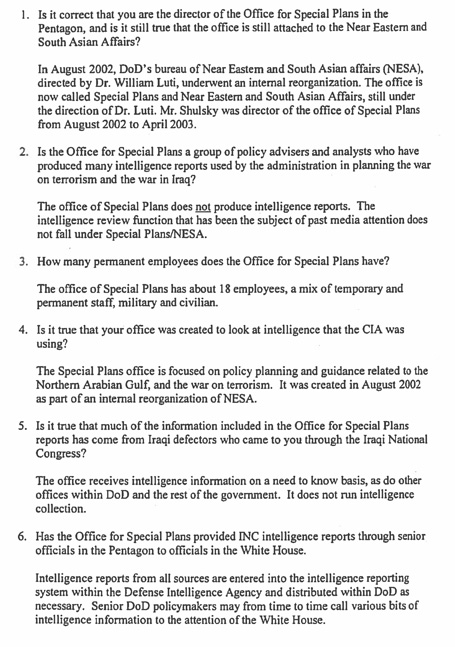

Answers 1 through 8 from the Department of Defense. Document 33.

The DoD public affairs response (Document 33) consisted of answers to the 20 questions posed byThe New Yorker. The information in the response related to personnel strength, its basic mission and reason for the office’s creation, its role (or lack of) in intelligence production, whether the office had disputes over the validity of intelligence data with the CIA and State Department, the activities of specific individuals believed to be associated with the Special Plans unit, and whether Special Plans employees referred to themselves as “The Cabal.”

The DoD briefing (Document 35), which included participation from Feith and Luti, followed The New Yorker article and disputed several of its statements (thus, repeating some of the comments made in the DoD response to The New Yorker‘s questions). Among the assertions disputed by Feith was that the Special Plans unit was responsible for reviewing intelligence concerning terrorist organizations and their state sponsors. He stated, “it’s a policy planning office.” He also asserted that “the reports that were obtained from the debriefings of these Iraqi defectors were disseminated in the same way that other intelligence reporting was disseminated, contrary to one particular journalist account who suggested that the Special Plans Office became a conduit for intelligence reports from the Iraqi National Congress to the White House,” adding, “That’s just flatly not true.”13

Policy Counterterrorism, 2002-2003 and Beyond

In the DoD briefing (Document 35), Feith did not dispute that he formed a team to review intelligence concerning terrorist groups and their sponsors — just that it was not the Office of Special Plans.

During the briefing he told his audience that after September 11, he “identified a requirement to think through what it means for the Defense Department to be at war with a terrorist network.” Thus, he asked some people “to review the large amount of intelligence on terrorist networks, and to think through how the various terrorist organizations relate to each other and how they relate to different groups that support them; in particular, state sponsors. And we set up a small team to help digest the intelligence that already existed on this very broad subject. And the so-called cell comprised two full-time people.” He added that “I think it’s almost comical that people think that this was set up as somehow an alternative … to the intelligence community or the CIA.”14

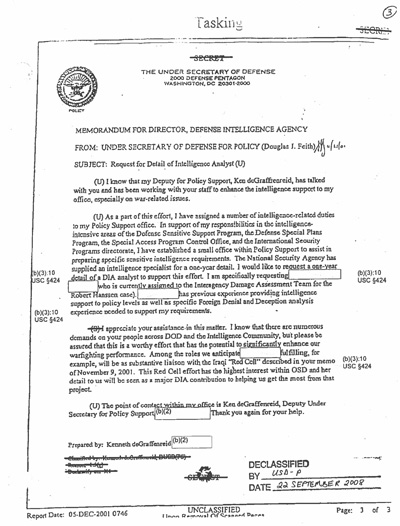

Douglas J. Feith, Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Memorandum for Director, Defense Intelligence Agency, Subject: Request for Detail of Intelligence Analyst, December 5, 2001. Secret. Document 37.

As with the Office of Special Plans, there are a series of released memos depicting the origins of the intelligence review office. An apparently initial, undated (but no later than December 5, 2001), memorandum (Document 37) from Feith to Vice Adm. Thomas R. Wilson, the director of DIA, requested detail of an intelligence analyst. The memo noted that Feith had assigned “a number of intelligence-related duties to my Policy Support office,” that he had established “a small office … to assist in preparing specific sensitive intelligence requirements, and that the National Security Agency had supplied an intelligence specialist for a year. One anticipated aspect of the analyst’s duties, Feith notes, would be as “substantive liaison” to a DIA Iraqi “Red Cell.”15

That memo to Wilson did not assign a name to the “small office” — and referred to a two-person team established in October 2001 to examine the connections between terrorist groups and state sponsors. In his memoir, Feith wrote that “as the need for actionable intelligence became more apparent, I determined to get help in reviewing the intelligence that already existed on terrorist networks.” He further elaborated that “a vast quantity of intelligence reporting routinely landed on my desk, including ‘raw’ intelligence reports … It was my responsibility to make use of the reports and for this I needed staff assistance.” The two individuals Feith assigned to provide assistance were David Wurmser, a John Hopkins University Ph.D. and an intelligence officer in the Naval Reserve, and Michael Maloof, “a veteran Defense Department professional” who specialized in analyzing international criminal networks.16

The result of their work was a 154-slide presentation, Understanding the Strategic Threat of Terror Networks and their Sponsors — described in one account as a “sociometric diagram of the links between terrorist organizations and their supporters around the world.”17 Among the key observations, Feith informed Senator John Warner in June 2003 (Document 43A), was that “terrorist groups and their state sponsors often cooperated across ideological divides (secular vs. religious; Sunni vs. Shi’a) which some terrorism experts believed precluded cooperation.

By January 2002, both Wurmser and Maloof had left their positions. On January 22, Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz sent a short memo to Feith titled “Iraqi Connections to Al Qaida,” that stated, “we don’t seem to be making much progress pulling together intelligence on links between Iraq and Al Qaida,” and added, “We owe SecDef some analysis of this subject.”18

On January 31, Peter W. Rodman, the assistant secretary of defense for international security, requested and received (Document 38) Feith’s approval — probably at Feith’s request — to establish a Policy Counter Terror Evaluation Group (PCTEG) “to conduct an independent analysis of the Al-Qaida terrorist network.”19 It specified four elements of PCTEG studies — studying al-Qaida’s worldwide organization (including its suppliers, its relations with States and with other terrorist organizations), identifying “chokepoints” in cooperation and coordination, identifying vulnerabilities, and recommending strategies to render the terrorist networks ineffective.

As recommended by Rodman, Feith signed a February 2, 2002, memo (Document 39) to DIA director Wilson informing him of the creation of a Policy Counter Terrorism Evaluation Group and what it would be doing. In addition, he asked for three individuals — two working for the DIA element that supported the Joint Staff – to be assigned to the group for 90 days. Approximately two weeks later, Wilson responded (Document 40), informing Feith that he could assign two of the three requested individuals to the evaluation group. While their names are deleted from Wilson’s response, numerous accounts identified one as Chris Carney, a naval reservist and subsequently a congressman (2007-2011).20

But even before Feith’s request for assistance, the PCTEG had produced an initial analysis of the links between al-Qaida and Iraq — according to a February 21, 2002, memo (Document 41) from Rodman to Feith. The memo told the deputy under secretary that a further analysis would follow in two weeks — and would include suggestions “on how to exploit the connection” between al-Qaida and Iraq and recommend strategies.

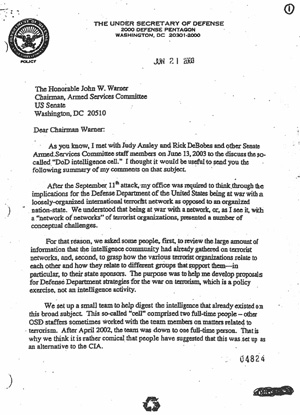

Douglas J. Feith, Under Secretary of Defense, to The Honorable John Warner, June 21, 2003. Unclassified. Document 43.

In a pair of June 21, 2003, letters (Document 43A,Document 43B) to Senate Armed Services Committee chairman John Warner and Rep. Jane Harman, Feith informed them that in the summer of 2002 the one remaining group member, along with an OSD staffer, produced a briefing, Assessing the Relationship between Iraq and al Qaida.21 It was first presented to the secretary of defense on August 8, and then, on August 15, DCI George Tenet and several other members of the CIA. A meeting between Feith’s representatives and Intelligence Community experts followed on August 20. In September, the briefing was presented to Stephen Hadley and I. Lewis Libby, chief of staff for the Office of the Vice President. Subsequently, Feith reported, the one-member team focused on “related issues, including work in support of the interrogation of al Qaida detainees,” until January 2003 when the final member of PCTEG departed.22

A “Key Questions” slide posed four questions which concerned the probability that there were contacts between Iraq and al Qaida; the probability that there was cooperation regarding such support functions as finances, expertise, training, and logistics; the probability that Iraq and al Qaida actually coordinated decisions or operations; and the probability that if a relationship existed, Iraq and al-Qaida could conceal its depth and characteristics from the United States.23

The only unclassified substantive slide from any of the briefings (Document 42) is titled “Fundamental Problems with How Intelligence Community is Assessing Information.” It identified three perceived problems — that the IC was applying a standard it would not normally employ, that there was a consistent underestimation of the importance Iraq and al-Qaeda would attach to concealing a relationship between the two, and that there was an assumption that secularists and Islamists will not cooperate, even when they have common interests.” That slide was not employed in the briefing to Tenet because, according to Feith, “it had a critical tone.”24

Another slide presented in the briefings was titled “What Would Each Side Want from a Relationship?” It identified one Iraqi objective — to obtain “an operational surrogate to continue war.” Another, titled “Summary of Known Iraq-al Qaida Contacts,1990-2002,” noted an alleged meeting between 9/11 hijacker Mohammed Atta and an Iraqi intelligence officer stationed in Prague. A slide that was employed in the September briefing, but not the others, was titled “Facilitation: Atta Meeting in Prague.” A slide titled “Findings” discussed alleged contacts, cooperation, and shared interests between Iraq and al-Qaida. It also contained a statement about coordination between Iraq and al-Qaida on 9/11 — with the exact wording differing from briefing to briefing. Five findings common to all the briefings were: “more than a decade of numerous contacts,” “multiple areas of cooperation,” “shared anti-US goals and common bellicose rhetoric — Unique in calling for killing of Americans and praising 9/11,” and “shared interest and pursuit of WMD,” and the “relationship would be compartmented by both sides, closely guarded secret, indications of excellent operational security by both parties.” The briefing for the secretary of defense asserted there was “one indication of Iraqi Coordination with al-Qaida,” while the briefing for Hadley and Libby stated there “were some indications of possible Iraqi coordination with al-Qaida.” In the briefing to Tenet, the slide claimed there was “one possible indication of Iraqi coordination with al-Qaida.”25

Feith’s efforts to dispell concern about the PCTEG continued , later that month, with a one-page “Fact Sheet on So-Called Intel Cell (or Policy Counter Terrorism Evaluation Group, PCTEG)” (Document 44). The fact sheet noted that the group’s focus was analysis of “the connections among terrorist groups and their government supporters in Iran, Syria, Iraq, Libya, Saudi Arabia, and the Palestinian Authority” — specifics not provided in earlier memos or statements. The fact sheet also reported that by April 2002 the PCTEG had decreased to one staffer, that it did not focus on the issue of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, and that the Iraq-al-Qaida briefing grew out the PCTEG’s review of interconnections among terrorist groups and “the discovery by a staffer of some intelligence reports of particular interest.” The one-pager would not defuse the controversy over the organizations established under Feith’s tenure, with a number of articles continuing to repeat the disputed claims.26

In October 2004, Senator Carl Levin (D-Michigan) issued a 46-report (Document 45A), entitledReport of an Inquiry into the Alternative Analysis of the Issue of an Iraq-al-Qaeda Relationship, which consisted of two key parts. One focused on what Levin characterized as the development and dissemination of an “alternative” assessment of the relationship between Iraq and al-Qaida. That assessment, he argued, “went beyond the judgments of intelligence professionals in the [Intelligence Community], and … resulted in providing unreliable intelligence information about the Iraq-al-Qaeda relationship to policymakers.” Another presented Levin’s argument that the alternative analysis became the preferred view of the Bush administration concerning any Iraq – al Qaida connection, in contrast to the judgments reached by the Intelligence Community — which were more skeptical than those of Feith’s group.

A somewhat different, although overlapping, focus can be found in a report (Document 45B) issued by the Republican Policy Committee in February 2006. Among the issues it addressed was the organization and functions of the Office of Special Plans, the nature of the PCTEG, whether the PCTEG collected its own intelligence regarding an Iraq-al Qaida connection, whether the alternative work on the Iraq-al Qaida connection was hidden from the Intelligence Community, and whether it was wrong for staff from the Office of the Secretary of Defense to question Intelligence Community analysis. It also posed the question whether Senator Levin had evidence for “his allegations about deception of Congress?” — specifically the allegation that Feith inaccurately told congressional committees that DOD made CIA-requested changes to a document that DOD delivered to the committees. The policy committee claimed that “the CIA has confirmed in writing that DOD did, in fact, make all the CIA-requested changes.”

Photo right: Cover to Document 47.

Photo right: Cover to Document 47.

The DoD Inspector General published a more detailed report in February 2007 (Document 47) — Review of the Pre-Iraqi War Activities of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy —many of whose key findings were presented in a briefing on the report (Document 46). The report was the result of requests by two senators. One was Senator Pat Roberts (R-Kansas), who at the time was chairman of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. On September 9, 2005, he requested a review of whether the Office of Special Plans “at any time conducted unauthorized, unlawful or inappropriate intelligence activities.” The other senator was Carl Levin, who about two weeks after the Roberts request, also asked the inspector general to review the activities of the under secretary of defense for policy, including the PCTEG and Policy Support Office, “to determine if any of the activities were either inappropriate or improper and if so, to provide recommendations for remedial actions.”27

Since, as the report noted, the “actual Office of Special Plans had no responsibility for and did not perform any of the activities examined in this review,” the report focused on the activities of the Policy Support Office and PCTEG. It defined its objective as being “to determine whether personnel assigned to the [Office of Special Plans, the Policy Counterterrorism Evaluation Group, and the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy] conducted unauthorized, unlawful, or inappropriate intelligence activities from September 2001 through June 2003.”28

The Inspector General’s primary conclusion was that the “Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy … developed, produced, and then disseminated alternative intelligence assessments on the Iraq and al Qaida relationship, which included some conclusions that were inconsistent with the consensus of the Intelligence Community, to senior decision makers.” While such actions were not, in the inspector general’s opinion, “illegal or unauthorized, the actions were … inappropriate given that the products did not clearly show the variance with the consensus of the Intelligence Community and were, in some cases, shown as intelligence products.” In addition, the inspector general concluded that, as a result, Feith’s office “did not provide ‘the most accurate analysis of intelligence’ to senior decision makers.”29

The intelligence assessments the report referred to essentially constituted the briefing Assessing the Relationship between Iraq and al Qaida. With regard to the study on Understanding the Strategic Threat of Terror Networks and their Sponsors, the inspector general noted that it served as “an example of an appropriate application of intelligence information.” But with regard to the August/September briefings, it pointed to various CIA and DIA reports that, it judged, did not support some of the findings stated in the briefing. The CIA reports included a June 21, 2002, document titled Iraq and al-Qaida: Interpreting a Murky Relationship and an August 20, 2002, draft, Iraqi Support for Terrorism. DIA products cited by the report included a July 31, 2002, assessment, Iraq’s Inconclusive Ties to Al-Qaida and an August 9, 2002, memorandum by an analyst with the agency’s Joint Intelligence Task Force Combating Terrorism — “JITF-CT Commentary: Iraq and al-Qaida, Making the Case.” The latter was a response to a paper, “Iraq and al-Qaida, Making the Case,” that was reportedly the basis of the August and September briefings.30

By the time the Inspector General’s report was published, Feith had left government, so the official, 47-page, response came from his successor — Eric S. Edelman.31 The response, as published in the Inspector General’s report, consisted of the comments on the draft version of the report but serve as a response to the final report in the many areas where the two were the same.

Among the comments was the assertion that the briefing’s reference to a “cooperative” relationship between Iraq and al-Qaida “was consistent with the DCI’s own comments to Congress in 2002 and 2003.” In addition, Edelman argued that “senior decision-makers already had the IC’s reports and assessments on Iraq and al-Qaida,” thus they “already had ‘the most accurate intelligence'” — that is, he noted, “if one accepts, as the Draft Report seems to do, that the IC’s assessments are the ‘most accurate.'” He also objected that, since no laws were broken or DoD directives violated, there was no reason to characterize the work as inappropriate. In addition, “The Secretary, and by extension, the Deputy, unequivocally had the latitude to obtain an alternative, critical assessment of IC work on Iraq and al-Qaida from non-IC OSD staff members rather than from the DIA or the Assistant Secretary of Defense for C3I, without vetting such critique through any Intelligence Community process.”32

Conclusion

The term “special plans” was coined over seventy years ago as a euphemism for deception, and subsequently became a euphemism for perception management, one element of which was deception. Thus, confusing actual or potential enemies was always an objective of special plans activities. During the George W. Bush administration the term produced confusion of a different kind — including over attempts to sort out the activities of components of the Defense Department’s policy office.

THE DOCUMENTS

DECEPTION AND PERCEPTION MANAGEMENT, 1946-1980.

Document 1: Office of the Chief of Staff, War Department, Memorandum, Subject: Cover and Deception, July 5, 1946. Top Secret

Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

This memo assigns responsibility for the supervision of War Department cover and deception matters to the Director of Plans and Operations — including supervision and training as well as preparation of future military strategic cover and deception plans and policies. It also assigns the director responsibility for evaluating the results of World War II cover and deception activities.

Document 2: Office of the Adjutant General, War Department, Memorandum, Subject: Tactical Cover and Deception, July 8, 1946. Top Secret.

Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

Responsibility for tactical deception to be employed by ground forces is assigned, by this memo, to the Commanding General, Army Ground Forces. It identifies three specific types of units involved in tactical deception activities — radio, sonic, and camouflage.

Document 3: Maj. Gen. George C. McDonald, Assistant Chief of Air Staff -2, to Commanding General, Army Air Forces, Subject: Army Air Force Cover and Deception Organization, n.d., circa 1946. Top Secret.

Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

This memo, from an Air Force Assistant Chief of Staff to the commander of the Army Air Forces addresses the issue of an Army Air Force cover and deception organization. It notes use of cover and deception during World War II, the current absence of such an organization and need to establish one, as well as suggesting responsibilities for various Army Air Force officials and components in a cover and deception effort.

Document 4: Headquarters, Army Air Forces, Memorandum, Subject: Establishment of Headquarters, Army Air Forces Cover and Deception Organization, n.d. Top Secret.

Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

This memorandum, to the assistant chiefs of the Air Staff, following up General McDonald’s recommendation (Document 3), directs establishment of an Army Air Forces Cover and deception organization and assigns responsibilities to different assistant chiefs of staff. (It is not clear whether such an organization was ever established).

Document 5: Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Department of the Navy, Memorandum for the Acting Chairman, United States Evaluation Board, Subj: Rewrite of USEB Charter, September 28, 1976. Secret.

Source: National Archives and Records Administration.

This memo, from the Director of Naval Intelligence, is addressed to the Acting Chairman of the “United States Evaluation Board.” The memo notes that the board was established “for cover and deception purposes,”with counterintelligence agencies being responsible for CFAs/DAs (presumably ‘controlled foreign agents’ and ‘double agents’), and the role of the Evaluation Board in processing “feed material” — information or documents to be passed to foreign intelligence services via the CFAs/DAs.

Document 6: Joint Chiefs of Staff, JCS Pub 4, Joint Chiefs of Staff Organization and Functions Manual, 1980 (Extract)

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

This extract from the Joint Chiefs of Staff 1980 organization and function manual discloses the existence of a Special Plans Branch within the Joint Staff and its responsibility to “provide guidance and instructions to appropriate agencies on the conduct of special planning (perception management) activities.”

Document 7: Joint Chiefs of Staff, “Perception Management: Iran,” 1980. Secret.

Source: DoD Freedom of Information Act Release.

This memo was written during the hostage crisis that began with the seizure of the U.S. Embassy in Tehran on November 4, 1979. Its purpose is stated as outlining a concept for employing psychological operations in support of resolving the “crisis in Iran on terms favorable to the interests of the United States.” It summarizes the situation, specifies assumptions, target groups, potential themes, and the concept — including both the organization and management of the effort as well as twelve possible measures.

Document 8A: Maj. Gen. Jack V. Mackmull, Commander, John F. Kennedy Center for Military Assistance, Subject: Psychological Operations Plan – Iranian Hostage Crisis, February 14, 1980. Secret.

Document 8B: Colonel Alfred H. Paddock Jr., Headquarters, 4th Psychological Operations Group, Subject: Psychological Operations Plan – Iranian Hostage Plan, February 13, 1980. Secret w/att: Statement of PSYOP Objective. Secret.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

General Mackmull’s February 14 letter transmits the February 13 letter and attached document from Colonel Paddock of the 4th Psychological Operations Group. Paddock’s letter notes the specific objectives of expanding the National Strategic Psychological Operations Plan to address the “captors” responsible for the seizure of the U.S. embassy in Tehran. The attached plan provides a statement of PSYOP objectives, defines the target audience, states themes, assesses effectiveness, and offers conclusions.

Document 9: Lt. Col. [Deleted], Memorandum to JCS, Subject: Strategic Political [Deleted], March 6, 1980, Confidential. w/att: Memorandum for the Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff, Subject: Strategic/Political [Deleted] RICE BOWL Ops, March 6, 1980. Top Secret.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

This memo, whose title is partially redacted, concerns psychological operations to be conducted during Operation RICE BOWL — the planning phase of Operation EAGLE CLAW, the attempted U.S. mission to rescue American hostages in Tehran in April 1980.

Document 10: Joint Staff, Memorandum to Major General Vaught, Subject: Background Option Papers, May 16, 1980. Top Secret.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

One of the background option papers prepared by the Joint Staff included one on “interim non-violent options.” Those included a rumor campaign, dropping of leaflets, interdiction of the Tehran power grid, a supersonic overflight by an SR-71 (accompanied by photo flash bombs), and periodic semi-overt probes of Iranian air space.

Document 11: Colonel [Deleted], Chief of Staff, Memorandum for Major General Vaught,Subject: “Backburner,” June 2, 1980. Secret.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

This memo reveals the existence of a perception management effort designated “Backburner” but provides no specifics. It does recommend some actions in support of the plan — including withdrawal of the U.S. carrier task groups from the Indian Ocean and employing hostage families to create “an illusion of well being among the hostages.”

Document 12: Lt. Col. [Deleted], Memorandun for General Vaught, Subject: Psychological Operations Support for SNOWBIRD, June 2, 1980. Secret.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

This memo discusses possible psychological operations in support of a second possible attempted mission to rescue U.S. hostages in Iran. Included among the possible operations were “small actions and communications” to indicate that the US was beginning to have second thoughts about employing military force. The memo also noted that some of the actions proposed “are on very tenuous legal ground.”

Document 13: Department of Defense, Department of Defense Telephone Directory, August 1980 Unclassified. (Extract)

Source: U.S. Government Printing Office.

These pages from the August 1980 issue of the Department of Defense’s telephone directory indicates the existence of a Special Plans Branch within the Joint Staff’s Special Operations Division.

PERCEPTION MANAGEMENT AND SPECIAL PLANS, 1981-1990

Document 14: Central Intelligence Agency, “DCI’s Schedule for Wednesday, 8 April 1981,” April 8, 1981. Secret.

Source: www.cia.gov/err

This page from DCI William Casey’s schedule includes an entry for a meeting on the Defense Department’s “strategic deception program” — a briefing given by Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Review Gen. Richard Stillwell as well Lt. Gen. Philip Gast, the chief of operations for the Joint Staff.

Document 15: John H. Stein, Acting Deputy Director for Operations, Memorandum for: Director of Central Intelligence, Subject: Briefing Provided Acting DDO by General Tighe and General Stillwell, April 24, 1981. Secret.

Source: CIA Records Search Tool (CREST).

This memorandum from the CIA’s acting deputy director of central intelligence for the Director of Central Intelligence reported on a briefing Stein received from General Stillwell (Document 14) and the director of the Defense Intelligence Agency “on their special project” — which may be a reference to the DoD perception management/deception program.

Document 16: Major General E. R. Thompson to Mr. John Stein, April 23, 1982. Top Secret.

Source: CREST.

This letter to CIA deputy director of operations John Stein is signed by Major General E. R. Thompson, who had served as the Army assistant chief for intelligence, and who the letter identifies as the director of the Defense Special Plans Office (DSPO). The letter focuses on the need for resources to operate the office. It also notes the existence of a charter for the DSPO and an Operational Capabilities Tasking memorandum (copies of which were attached to the letter but not released).

Document 17: Martin Hurwitz, Director, General Defense Intelligence Program, to Mr. James S. Wagenen, June 11, 1982. Secret.

Source: CREST.

This letter, from the director of the General Defense Intelligence Program, responds to a request from a staff member of the House Appropriations Committee for sources of funds, via realignment, for the Defense Special Plans Office.

Document 18: Charles W. Hinkle, Director, Freedom of Information and Security Review, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense, to Dr. Jeffrey Richelson, July 25, 1983. Unclassified w/att: General Richard G. Stilwell, Deputy Under Secretary of Defense, Memorandum for the Director, Washington Headquarters Services, Subject: Cancellation of DoD Directives TS-5155.2 and C-5155.1, February 2, 1983. Unclassified.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

In response to a June 22, 1983 Freedom of Information Act for copy of the organization chart and mission statement for the Defense Special Plans Office, the DoD’s Director of Freedom of Information and Security Review stated that “no such office exists” and encloses a relevant memorandum. The memorandum explains that the office did exist and why it no longer did as of July 25, 1983.

Document 19: Charles W. Hinkle, Director, Freedom of Information and Security Review, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense, to Mr. R. Scott Armstrong, July 25, 1983.Unclassified.

Source: R. Scott Armstrong.

This DoD response to FOIA requests by Washington Post writer Scott Armstrong for records related to the Defense Special Plans Office states that the DoD copies of the directives were classified in their entirety — as were all other documents cited in the letter, including those related to the office’s creation and budget and accounting issues.

Document 20: Department of Defense, Department of Defense Telephone Directory, December 1983, Unclassified. (Extract)

Source: U.S. Government Printing Office.

While the DSPO no longer existed as of December 1983, the Special Plans units in the Special Operations Division and the Defense Intelligence Agency (created subsequent to August 1980) remained in existence — and occupied adjoining suites in the Pentagon — as indicated by this extract from the December 1983 Department of Defense Telephone Directory.

Document 21: Joint Chiefs of Staff, Report* by the J-3 to the Joint Chiefs of Staff on Special Plans Overview Guidance, August 9, 1985. Top Secret.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

The title of this almost entirely redacted document indicates that, in 1985, the Joint Chiefs of Staff produced an overview guidance for special plans activities. (A recent request for the document produced a ‘no records’ response).

Document 22: John H. Fetterman, Jr. Deputy and Acting Chief of Staff, U.S. Atlantic Command, Subj: Deception Planning Organization, October 28, 1985, Confidential.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

This Atlantic Command instruction illustrates the existence of deception planning organizations not only at the Defense Department and defense agency level but also at the unified commands. Among the topics discussed were planning considerations as well as ‘Special Means and Feed Material’ — that is use of agents of deception and the material to be fed to deception targets.

Document 23: Lt. Richard A. Burpee, Director of Operations, Joint Staff, SM-224-87, Subject: Special Plans Guidance – Strategic Defense, April 6, 1987. Top Secret.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

A key element of the Reagan administration’s defense policy was strategic defense, which included the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), better known as ‘Star Wars.’ This document, most which has been redacted, focuses on special plans related to U.S. strategic defense programs. It notes a number of areas that “may warrant additional review when considering [perception management] support of Strategic Defense.”

Document 24: Joint Chiefs of Staff, JCS Admin Pub 1.1, Organization and Functions of the Joint Staff, October 1, 1988. Unclassified. (Extract)

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release

This extract from the Joint Chiefs of Staff organization and functions manual shows the structure of the J-3 (Operations) directorate of the Joint Staff and the locus of Special Plans management for the JCS in the directorate’s Operations Planning and Analysis Division. It also reveals the existence of an “Interdepartmental Special Plans Working Group.”

Document 25: United States Central Command, Regulation 525-3, Military Deception Policy and Guidance, August 11, 1990. Secret.

Source: Central Command Freedom of Information Act Release.

As did the 1985 Atlantic Command instruction (Document 22) this document concerns military deception activity at the unified command level. It notes that US military deceptions “shall not be designed to influence the actions of US citizens or agencies, and they will not violate US law, nor intentionally mislead the American public, US Congress, or the media.”

Document 26: General Accounting Office, GAO/NSIAD-94-219, Ballistic Missile Defense: Records Indicate Deception Program Did Not Affect 1984 Test Results, July 1994. Unclassified.

Source: http://gao.gov

This GAO report was produced in response to a request by a member of Congress that the office investigate claims made in 1993 of DoD deception in its June 1984 ballistic missile defense test – Homing Overlay Experiment 4 (HOE 4). It reports on DoD’s acknowledgment of a deception program associated with the HOE, that there was no evidence that DoD deceived Congress about HOE 4 intercepting its target (although the department did not disclose how it made interception easier), and that plans for a deceptive explosion was dropped prior to the test in the event of a near miss.

SPECIAL PLANS, 2002 – 2003

Document 27: Douglas J. Feith, Undersecretary of Defense, For: Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for White House Liaison, Subject: Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Special Plans and Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs (SP/NESA), August 23, 2002. Unclassified.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release

This memo, from Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Douglas Feith, announces his plans to create a Directorate of Special Plans within the office of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs. The directorate, Feith explained, was to assume responsibility within his office for the war on terrorism. Feith requests approval of his nominee to head the new office.

Document 28: Jacqueline G. Arends, Special Assistant to the Secretary for White House Liaison, For: Deputy Secretary of Defense, Subject: Candidate Approval Position Adjustment – Liu, September 13, 2002. Unclassified w/att: Douglas J. Feith, Under Secretary of Defense, For: Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense for White House Liaison, Subject; Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Special Plans and Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs (SP/NESA), August 23, 2002. Unclassified.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

This memo from the special assistant to the Secretary of Defense for White House Liaison to the Deputy Secretary of Defense requests approval to establish the office proposed by Feith in his August 23 memorandum (Document 27) as well as to appoint William Luti to the position.

Document 29: OSD/SP/NESA, “Pros and Cons of a Provisional Government,” October 10, 2002, Secret/Noforn.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

The organizational authorship attributed to this memo concerning the formation of a provisional Iraqi government — “OSD/SP/NESA” — indicates the memo is a product of the Special Plans component of the Office of the Secretary of Defense.

Document 30: Assistant Director for Executive and Political Personnel, To: Director, Personnel and Security, Director of Administration and Management, Subject: Establishment of the SES General Position of Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Special Plans & Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs) and Noncareer Reassignment of William J. Luti, October 13, 2002. Unclassified w/att: Approval/certification, October 21, 2002. Unclassified.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release

This memo follows up on the earlier memos from Feith (Document 27) and Arends (Document 28) on creation of the position of Deputy Under Secretary of Defense (Special Plans & Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs). It describes the position as advising and exercising “responsibility for all policy matters of Defense interest pertaining to special plans and the defense policy on the countries of the Middle East and South Asia.” It recommends approval of the proposed position and nominee — recommendations which the last page indicates were accepted.

Document 31: Department of Defense, Deputy Under Secretary of Defense Special Plans and Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs, n.d. Unclassified.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

This document describes, inter alia, the nature and purpose of the position of the Deputy Under Secretary of Defense Special Plans and Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs.

Document 32: Department of Defense, Office of Special Plans and Near East and South Asian Affairs: Expansion to Deal with Iran, Iraq, and the War on Terrorism, circa late 2002- 2003.

Source: www.waranddecision.com

These briefing slides, intended to describe the expansion of the Office of Special Plans and Near East and South Asian Affairs, includes a organization chart for the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, a description of the organization prior to October 2002, and a depiction of the post-October 2002 reorganization. The last chart indicates that the Director, Special Plans was responsible for “Iran, Iraq, War on Terrorism.”

Document 33: Office of Public Affairs, Department of Defense, Answers to Questions Posed by Seymour Hersh/The New Yorker, circa 2003.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

This document, consists of questions posed by The New Yorker/Seymour Hersh for a story being researched as well as the answers provided by the Department of Defense. The questions concerned the personnel strength, personnel histories, mission, and activities of the Office of Special Plans.

Document 34: Office of the Secretary of Defense/Special Plans/Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs, “Iraqi Opposition Strategy,” January 30, 2003, Secret.

Source: www.dod.mil/pubs/foi

This paper, prepared by the office of William Luti, Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Special Plans and Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs, focused on the strategy of the Iraqi opposition. Its states the office’s opposition to the State Department position with regard to the treatment of the external opposition to Saddam’s regime and discusses a number of specific issues (including the Judicial Council, Consultative Council, and Census).

Document 35: Department of Defense, News Transcript, DoD Briefing on Policy and Intelligence Matters, June 4, 2003. Unclassified.

Source: www.defenselink.mil

The briefing covered in this transcript involved participation by Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Douglas J. Feith and Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Special Plans and Near East and South Asian Affairs William J. Luti. Among the topics to be discussed, Feith noted at the beginning of the briefing was the “so-called, or alleged intelligence cell and its relation to the Special Plans Office.”

Document 36: William J. Luti, Deputy Under Secretary of Defense, Memorandum for: Principal Director, Organizational Management, and Support OUSDP, Subject: Office Redesignations, July 14, 2003. Unclassified.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release.

This memo from William J. Luti requests that his office designation be changed to Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Near Eastern and South Asian Affairs and that the title of Director for Special Plans be changed to Director for Northern Gulf Affairs.

POLICY COUNTERTERRORISM EVALUATION GROUP, 2002 – 2008

Document 37: Douglas J. Feith, Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Memorandum for Director, Defense Intelligence Agency, Subject: Request for Detail of Intelligence Analyst, December 5, 2001. Secret.

Source: www.dod.gov/pubs/foi

In this memorandum to the Director of the Defense Intelligence Agency, Under Secretary of Defense for Policy Douglas Feith notes that he had “assigned a number of intelligence-related duties to my Policy Support office,” requests that a DIA analyst be detailed for a year to help carried out those duties, and notes that the National Security Agency had responded favorably to a similar request. Feith’s memo also reveals the existence of a Defense Special Plans Program, in a context which suggests that Special Plans was being used as a euphemism for perception management.

Document 38: Peter W. Rodman, Assistant Secretary of Defense International Security Affairs, to Under Secretary of Defense (Policy), Subject: Policy Evaluation Group (PCTEG), January 31, 2002 Secret.

Source: Department of Defense Freedom of Information Act Release

This memo, from the assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs, to deputy under secretary Feith, requests his approval to established a Policy Counter Terror Evaluation Group “to conduct an independent analysis of the Al-Qaida terrorist network.” It goes on to specify what subjects the group would focus on. Feith indicates his approval at the end of the memo.

Document 39: Douglas J. Feith, Memorandum for Director, Defense Intelligence Agency, Subject: Request for Support, February 2, 2002. Secret.

Source: www.dod.gov/pubs/foi

Similar to his memorandum of December 5, 2001 (Document 37) to the DIA director, deputy under secretary Feith requests the detail of three DIA analysts (by name) to become part of the Policy Counter Terrorism Evaluation Group — although he asks only for 90-day deployments. The memo also describes the focus of the group’s planned analytical effort.

Document 40: Vice Adm. Thomas R. Wilson, Director, Defense Intelligence Agency, to Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, Subject: Request for Support, February 15, 2002,. Confidential.

Source: www.dod.gov/pubs/foi

In his response to Feith’s request (Document 39), DIA director Thomas Wilson agrees to provide two of the request analysts to the PCTEG, who would serve with the group as U.S. Navy reservists.

Document 41: Peter W. Rodman, Assistant Secretary of Defense, International Security Affairs, to Deputy Secretary of Defense, Subject: Links between Al-Qaida and Iraq, February 21, 2002. Secret.

Source: www.waranddecision.com

This memo from international security affairs chief Rodman to Feith notes that the PCTEG had provided the results of their initial work on links between Al-Qaida and Iraq and restated the four components of the group’s analytical focus. It also promises to provide further analysis along with suggestions “on how to exploit the connection and recommend strategies.”

Document 42: Office of the Secretary of Defense, Assessing the Relationship Between Iraq and Al Qaida, n.d., August 2002. Classification Not Available.

Source: www.levin.senate.gov

The forerunner to the PCTEG produced a 154-page report on links between terrorist organizations and state sponsors of terrorism. A follow-up effort, focusing on links between al-Qaeda and Iraq, resulted in briefings to several briefings, including one to DCI George Tenet. The single substantive slide that has been released is one that was briefed to the Department of Defense, but not to the DCI.

Document 43A: Douglas J. Feith, Under Secretary of Defense, to The Honorable John Warner, June 21, 2003. Unclassified.

Document 43B: Douglas J. Feith, Under Secretary of Defense, to The Honorable Jane Harman, June 21, 2013. Unclassified.

Source: www.dod.gov/pubs/foi

These letters from Feith to chairman of the Senate Armed Services Committee and Representative Jane Harman concerns the “so-called ‘DoD intelligence cell.'” He writes that “we set up a small team to help digest the intelligence that already existed” on links between terrorist networks and state sponsors and that after April 2002 “the team was down to one full-time person.” He also addresses the work on the team member after April 2002 and the identification of the team with the Office of Special Plans.

Document 44: Under Secretary of Defense, Policy, Draft, “Fact Sheet on So-Called Intell Cell (or Policy Counterterrorism Evaluation Group, PCTEG), “February 3, 2004. Unclassified.

Source: www.dod.gov/pubs/foi

As with the letters to John Warner and Jane Harman (Document 43A, Document 43B) this document focuses on the “so-called Intell Cell” — the Policy Counter Terrorism Evaluation Group. This one-page fact sheet discusses the reason for establishing the group, the focus of its research, its product, and the size of the group.

Document 45A: Senator Carl Levin, Report of an Inquiry into the Alternative Analysis of the Issue of an Iraq-al Qaeda Relationship, October 21, 2004. Unclassified.

Document 45B: Republican Policy Committee, The Department of Defense, the Office of Special Plans and Iraq Pre-War Intelligence, February 7, 2006. Not classified.

Sources: www.levin.senate.gov, www.dougfeith.com

These two reports, from differing political perspectives address the interrelated issues of the analysis of the Iraq- al-Qaeda relationship produced by the PCTEG, the mission of the Office of Special Plans, and various reports about the Special Plans office’s activities.

Document 46: Inspector General, Department of Defense Report on Review of the Pre-Iraqi War Activities of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy (Report No. 07-INTEL-04), February 9, 2007. Unclassified.

Source: www.dodig.mil

These briefing slides summarize the purpose and results of the Department of Defense Inspector General’s report on the activities of the Office of Special Plans and PCTEG. It notes separate requests from Sen. Pat Roberts, a Republican, and Carl Levin (Document 45A) to review the activities of either the OSP or the PCTEG and Policy Support Office, states review objectives, the scope of the review, and findings. The final five slides provide answers to questions posed by Senator Levin.

Document 47: Inspector General, Department of Defense, 07-INTEL-04, Review of the Pre-Iraqi War Activities of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy, February 9, 2007. Secret/Noforn.

Source: www.dodig.mil

This report, whose origins and reports are summarized in briefing slides released the same day (Document 46) was released in redacted form by the DoD Inspector General’s Office. It provides background to its origins, describes its results, and presents its evaluation — which includes the statement that “The assessments produced evolved from policy to intelligence products, which were then disseminated” and that such actions “were inappropriate because a policy office was producing intelligence products and was not clearly conveying to senior decision-makers the variance with the consensus of the Intelligence Community.”

Document 48: U.S. Senate, Select Committee on Intelligence, Intelligence Activities Relating to Iraq Conducted by the Policy Counterterrorism Evaluation Group and the Office of Special Plans Within the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy , June 2008. Unclassified.

Source: www.senate.gov

Despite its title, this report largely focuses on one particular incident – a meeting in Rome that occurred between December 10 and December 13, 2001. The meeting involved a number of DoD officials, including one who subsequently became a member of the Office of Special Plans, and Iranian exiles.

NOTES

[1] On the multiple forms of deception and the components of perception management see, Joseph W. Caddell, Deception 101 – Primer on Deception, December 2004, available at: www.fas.org/irp/eprint/deception.pdf; Jeffrey T. Richelson, “Planning to Deceive,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Mach/April 2003, pp. 64-69.

[2] Michael Howard, British Intelligence in the Second World War, Volume 5: StrategicDeception (London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, 1990), p. 110; Thaddeus Holt, TheDeceivers: Allied Military Deception in the Second World War (New York: Skyhore Publishing 2007), p. 795. The book, originally published in 1975, that first popularized the history of World War II deception is Anthony Cave Brown, Bodyguard of Lies: The Extraordinary True StoryBehind D-Day (Guilford, Ct.: The Lyons Press, 2002).

[4] On LACROSSE and MISTY, see Jeffrey T. Richelson, The Wizards of Langley: Inside theCIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology (Boulder, Co.: Westview, 2001), pp. 247-249. On the Reagan administration’s concern with Soviet denial and deception, see Ronald Reagan, National Security Decision Directive 108, “Soviet Camouflage, Concealment and Deception,” October 12, 1983.

[5] In the same time period special plans units could found at both the service and command levels. Examples included the Special Plans Division of the Directorate of Plans of the Air Force office of the Deputy Chief of Staff, Plans & Operations; a Special Plans component of the Tactical Air Command; and the CINCPAC Special Plans Committee.

[6] Bob Woodward, “Gadhafi Target of Secret U.S. Deception Plan,” Washington Post , October 2, 1986, pp. A1, A12-A13; David M. North, “U.S. Using Disinformation Policy To Impede Technical Data Flow,” Aviation Week & Space Technology, March 17, 1986, pp. 16-17; “A Bodyguard of Lies,” Newsweek, October 13, 1986, pp. 43-46.

[7] The most recent known official document related to deception is: Department of Defense Instruction S-3604.01, “Department of Defense Military Deception,” March 11, 2013. (It is still classified.)

[8] Douglas J. Feith, War and Decision: Inside the Pentagon at the Dawn of the War onTerrorism (New York: Harper 2008), p. 293.

[13] See Ibid., pp. 44-45. The New Yorker article reportedly resulted in a letter to the magazine’s editor, David Remnick, from a senior DoD public affairs official in which the official complained that “There are more inaccuracies that can be addressed in this letter, and it is particularly disappointing given the time and effort taken by my staff to ensure The New Yorker has its facts straight prior to publication.” See, Bill Gertz and Rowan Scarborough, “Inside the Ring,” The Washington Times, May 21, 2004. A FOIA request for the letter produced a “no records” response from DoD.

[14] On the creation of this group — the Policy Counterterrorism Evaluation Group (PCTEG) — also see Feith, War and Decision, pp. 116-117.

[15] The memo also suggested that the term Special Plans continued, in some instances, to have its traditional association with deception/perception management — since it stated that Feith directed a number of activities that required sensitive intelligence support, including the “Defense Special Plans Program.”

[17] Inspector General, Department of Defense, Report 07-INTEL-04, Review of the Pre-IraqiWar Activities of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy , February 9, 2007, p.12; Priest, “Pentagon Shadow Loses Some Mystique.” Another examination of the activities of PCTEG and its untitled predecessor is by James Risen, “How Pair’s Finding on Terror Led To Clash on Shaping Intelligence,” New York Times, April 28, 2004, pp. A1, A19.

[18] Peter Spiegel, “Investigation fills in blanks on how war groundwork was laid,” Los AngelesTimes , April 6, 2007, p. A10.

[21] The one PCTEG member (Chris Carney) plus two OSD staffers (veteran DIA analyst Christina Shelton and James Thomas) produced and presented the briefing — as Feith noted in War and Decision , pp. 265-266.

[22] Inspector General, Department of Defense, Report 07-INTEL-04, Review of the Pre-IraqiWar Activities of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy , February 9, 2007, p.10; Feith, War and Decision, p.119n; Senator Carl Levin, Report of an Inquiry into the Alternative Analysis of the Issue of an Iraq-al Qaeda Relationship , October 21, 2004, pp. 14, 16. What Tenet said and thought about the briefing has been a subject of controversy — See Priest, “Pentagon Shadow Loses Some Mystique”; Feith, War and Decision, pp. 266-267; George J. Tenet with Bill Harlow, At the Center of the Storm: My Years at the CIA (New York: Harper Collins, 2007), pp. 346-348. The briefing and related issues are discussed at length in U.S. Congress, Senate Committee on Armed Services, Briefing on the Department of Defense Inspector General’s Report on the Activities of the Office of Special Plans Prior to the War inIraq (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 2008).

[23] Inspector General, Department of Defense, Report 07-INTEL-04, Review of the Pre-IraqiWar Activities of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy , p. 72

[26] See Jason Leopold, “CIA Probe Finds Secret Pentagon Group Manipulated Intelligence on Iraqi Threat,” www.Antiwar.com, July 25, 2003; Robert Dreyfuss and Jason Vest, “The Lie Factory,”Mother Jones, January/February 2004; Karen Kwiatowski, “The new Pentagon papers,” www.salon.com, March 10, 2004; James Bamford, A Pretext for War: 9/11, Iraq, andthe Abuse of America’s Intelligence Agencies (New York: Doubleday, 2004), pp. 307-308, 314-316, 318-320, 324; Peter Eisner and Knute Royce, The Italian Letter: How the Bush Administration Used a Fake Letter to Build the Case for War in Iraq (New York: Rodale, 2007), pp. 58-63.

[27] Inspector General, Department of Defense, Report 07-INTEL-04, Review of the Pre-IraqiWar Activities of the Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Policy , p. ii.

[30] Ibid., pp.7-9, 12, 14, 29. Declassified versions of the two CIA reports can be found at:http://www.fas.org/irp/congress/2005_cr/levin041505.html. The topic of Iraqi – al Qaida links is also the subject of Kevin M. Woods with James Lacey, Institute for Defense Analyses, Saddamand Terrorism: Emerging Insights from Captured Iraqi Documents, Volume 1 (Redacted), November 2007.

[31] Feith’s reaction appeared in War and Decision , pp. 270-271 as well as on his website — www.dougfeith.com