|

There was, during the course of the 2016 campaign, a small but vocal group of antiwar libertarians and conservatives who had convinced themselves that Donald Trump was preferable to Hillary Clinton because he, Trump, had made his (fictitious) opposition to the Iraq War a cornerstone of his candidacy.

Trump, some believed, was a Republican in the mold of Senator Robert Taft, someone who would turn away from neoconservative, interventionist orthodoxy.

Donald Trump speaking with supporters at a campaign rally at Fountain Park in Fountain Hills, Arizona. March 19, 2016. (Flickr Gage Skidmore) If, as the adage suggests, we can judge a man by his enemies, a cursory look at Trump’s most vocal Republican critics would seem to confirm this judgment. Why, here’s Bill Kristol in January 2016, asking “Isn’t Donald Trump the very epitome of vulgarity?” Commentary’s John Podhoretz declared that Trump “would be, unquestionably, the worst thing to happen to the American common culture in my lifetime.” Professor Eliot A. Cohen and his merry band of think tank militarists published an open letter in opposition to Trump’s candidacy while National Review convened a symposium of anti-Trumpers for a special issue titled “Against Trump.”

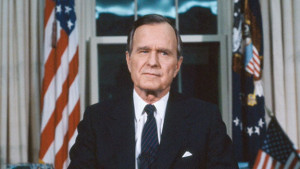

Perhaps, though, Kristol, Cohen, Podhoretz, NR and the rest needn’t have worried so. Trump, it turns out, seems every bit as captive to the bipartisan foreign policy consensus as was his predecessor. Many supporters of Barack Obama held the errant hope that Obama would finally break the cycle of wars begun a quarter-century ago when George H.W. Bush launched Operation Desert Storm against Iraq and in defense of desert petro-states, Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

Trump partisans may object that he’s only been in office for about two months. Give him time, they say. That’s fair enough, but it is worth reviewing Trump’s foreign policy record up to this point.

An administration’s budget is generally a reliable indicator of its priorities. Here we find, in Trump’s first budget proposal, nearly $11 billion in cuts to the U.S. Department of State, a cut of roughly 29 percent, while the Pentagon is budgeted for an additional $54 billion, an increase of 9 percent.

Afghanistan, where the U.S. has been at war for 15½ years, is by far American’s longest and perhaps most futile overseas engagement. Here the Trump administration seems intent on ratcheting up airstrikes on the Taliban in a departure from the narrower focus on anti-terrorism that characterized the late Obama administration policy.

The head of U.S. Central Command, U.S. Army Gen. Joseph Votel, told the Senate Armed Services Committee last week that he will recommend an increase in troops in order “to make the advise-and-assist mission more effective.” This comes on the heels of testimony by the top commander in Afghanistan, Army General John Nicholson telling Congress in February that he would need “a few thousand more” troops to carry out the mission.

More Troops

Meanwhile, more troops are being deployed to Kuwait. On March 9, the Army Times reported that the U.S. is sending “an additional 2,500 ground combat troops to a staging base in Kuwait from which they could be called upon to back up coalition forces battling the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria.” This is in addition to the already roughly 6,000 American troops that are currently in Syria and Iraq assisting in the fight against the Islamic State. American units are now in the northern Syrian city of Manbij and on the outskirts on Raqqa.

Saudi defense minister, Prince Mohammad bin Salman Al Saudi The latter deployment of Marines from the 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit marks, according to the Washington Post, “a new escalation in the U.S. war in Syria, and puts more conventional U.S. troops in the battle.” The Post, like all other mainstream outlets, leaves out mention that this new deployment is illegal under international law, a point Syrian President Bashar al-Assad made in an interview with Chinese state media last weekend.

And then, perhaps worst of all, there is the ongoing American support for Saudi Arabia’s war on Yemen. As Council on Foreign Relations analyst Micah Zenko recently pointed out, Trump has already “approved at least 36 drone strikes or raids in 45 days — one every 1.25 days.” These include, according to Zenko, “three drone strikes in Yemen on January 20, 21, and 22; the January 28 Navy SEAL raid in Yemen; one reported strike in Pakistan on March 1; more than thirty strikes in Yemen on March 2 and 3; and at least one more on March 6.” The strikes, we are told, are a necessary part of the “global war on terror” and are portrayed by military and administration spokesmen as such.

A Pentagon spokesman told longtime CNN stenographer Barbara Starr that the wave of 30 strikes on March 2 and 3 were “precision strikes in Yemen against al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula” in order to “maintain pressure against the terrorists’ network and infrastructure in the region.” The U.S.-Saudi war on Yemen has predictably resulted in a humanitarian catastrophe. According to the Brookings Institution’s Bruce Reidel,

“a Yemeni child dies every 10 minutes from severe malnutrition and other problems linked to the war and the Saudi blockade of the north.”

All this on behalf of our old friends the Saudis. In the decade and a half after aiding the 9/11 hijackers, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has, with American acquiescence, embarked on a campaign to destroy Yemen because of an illusory threat posed by Iran. Yet the reason behind KSA’s aggression on the southern end of the Arabian peninsula has not a bit to do with “security” or Iranian “aggression” or fighting “terrorism”; it is a sectarian campaign waged by Saudi extremists, nothing more. What could possibly be America’s interest in assisting the Saudis in such an endeavor?

Yet, despite the heinous nature of Saudi Arabia’s anti-Houthi campaign in Yemen, its mastermind, the young Saudi Defense Minister Prince Mohammed bin Salman, was treated to lunch at the White House with the President this week. In an ominous sign of things to come, a statement from the Saudis noted that Trump and bin Salman “share the same views on the gravity of the Iranian expansionist moves in the region.”

And so, to sum up: President Trump, in the space of two months, has proposed a budget that slashes funding for diplomacy, spends lavishly on military, has committed thousands of troops, conducted dozens of airstrikes, and cemented the U.S. commitment to the wars in Iraq, Syria, Yemen and Afghanistan for the foreseeable future. Meanwhile, he and his team have signaled to the Saudis that they fully share the Kingdom’s obsession with Iranian “expansion.”

An Unending Cycle

What can be done to break the seemingly unending cycle of American intervention in the Middle East? What all the aforementioned interventions have in common is that they are, as the constitutional lawyer and former Justice Department official Bruce Fein has pointed out, presidential wars, which he defines as “wars in which the President decides to take the United States from a state of peace to a state of war.”

President George H. W. Bush addresses the nation on Jan. 16, 1991, to discuss the launch of Operation Desert Storm.

Fein, a founding member of the anti-interventionist Committee for The Republic, has written at length on what he views as the steady erosion of the congressional prerogative in matters of war and peace. Fein writes that the Founders “unanimously entrusted to Congress exclusive responsibility for taking the nation to war in Article I, section 8, clause 11 of the Constitution” because they understood “to a virtual certainty that Congress would only declare war in response to actual or perceived aggression against the United States, i.e., only in self-defense.”

Accordingly, the Committee for The Republic has embarked on a timely project aimed at having “the House pass a resolution that defines presidential wars under the Constitution going forward and declares them unconstitutional in violation of Article I, section 8, clause 11 (Declare War Clause).” Furthermore, the “End Presidential Wars” project seeks a further resolution, which would warn “the President that such wars will be deemed high crimes and misdemeanors under Article II, section 4 of the Constitution resulting in his or her impeachment, conviction, and removal from office.”

Fein points to Alexis de Tocqueville’s observation in Democracy in America that,

“All those who seek to destroy the liberties of a democratic nation ought to know that war is the surest and shortest means to accomplish it.”

Unless we come to grips with our current mania for overseas intervention and find a remedy for Congress’s abdication of its constitutional responsibilities, we are doomed to remain in the 25-year grip of endless, counterproductive and illegal military interventions in the Middle East and beyond.

James W Carden is a contributing writer for The Nation and editor of The American Committee for East-West Accord’s eastwestaccord.com. He previously served as an adviser on Russia to the Special Representative for Global Inter-governmental Affairs at the US State Department.

|