Towards the Destabilization and Breakup of Thailand?

The Economist's Absurd "Divided Thailand" Commentary

The Economist has recently floated a narrative that the current Thai regime could flee to the north and “separate” the region from Thailand. Far from a legitimate government seeking to “preserve democracy,” it a Western-backed proxy regime carrying out the tried by true modern imperial agenda of divide and rule.

First, it should be remembered that the Economist publishes paid-for op-eds. It is not news, it is not analysis, it is simply the message told by the highest bidders – the corporate-financier interests of Wall Street and London. These interests are passed to the Economist via their impressive network of lobbying firms. The Economist itself sits among the corporate membership of large Wall Street-London policy think-tanks like the Chatham House, right along side these lobbying firms.

In their latest article, “Political crisis in Thailand: You go your way, I’ll go mine,” one of these lobbying firms comes to mind – fellow Chatham House corporate member Amsterdam & Partners. Robert Amsterdam is currently representing deposed dictator, accused mass murderer, and convicted criminal Thaksin Shinawatra, as well as his “red shirt” enforcers. It claims:

Indeed, many red shirts say Bangkok is already lost. Mr Suthep has nearly free rein there, closing down most government offices. The police have charged him with insurrection and seizing state property, but no attempt has been made to arrest him. The imposition of a state of emergency for 60 days may not make much difference.

Thus most red shirts in the north and north-east now contemplate—indeed they seem to be preparing for—a political separation from Bangkok and the south. Some can barely wait. In Chiang Mai a former classmate of Mr Thaksin’s says that in the event of a coup “the prime minister can come here and we will look after her. If…we have to fight, we will. We want our separate state and the majority of red shirts would welcome the division.” Be afraid for Thailand as the political system breaks down.

Thaksin Shianwatra is at the very center of Thailand’s current political crisis which includes the ongoing “Occupy Bangkok” campaign that has paralyzed the government for now nearly 2 weeks, and has drawn out the largest street protests in decades. Pro-government rallies have fizzled and many of the regime’s supporters, including rural farmers have in fact joined the opposition after being cheated in a vote-buying rice subsidy scam that has gone bankrupt and left them unpaid now for nearly half a year.

Why Secession is Impossible & Why the Lie is Being Repeated in Economist

It was in 2010 that the Asia Foundation conducted its “national public perception surveys of the Thai electorate,” (2010’s full .pdf here). In a summary report titled, “Survey Findings Challenge Notion of a Divided Thailand.” It summarized the popular misconception of a “divided” Thailand by stating:

“Since Thailand’s color politics began pitting the People’s Alliance for Democracy’s (PAD) “Yellow-Shirt” movement against the National United Front of Democracy Against Dictatorship’s (UDD) “Red-Shirt” movement, political watchers have insisted that the Thai people are bitterly divided in their loyalties to rival political factions.”

The survey, conducted over the course of late 2010 and involving 1,500 individuals, revealed however, a meager 7% of Thailand’s population identified themselves as being “red” Thaksin supporters, with another 7% identifying themselves only as “leaning toward red.”

Graph: Up from 62% the year before, the public perception of the military as an important independent institution stood at 63%. Even in in the regime’s rural strongholds, support stood at 61%. The only individually polled group that did show majority support for the military, was the regime’s tiny “red” minority, but even among them, 30% still supported the army. .

Since taking office, it has bankrupted a disastrous vote-buying rice subsidy and has subsequently failed to pay rice farmers, fumbled its response twice during catastrophic flooding in 2011 and again just this year – all while spending the vast majority of its time consolidating its power and attempting to exonerate Thaksin Shinawatra of his many crimes.

Conversely, it was the Royal Thai Army that came to the aid of the rural countryside when flooding hit, and assisted in both rescue and logistics during the floods, as well as cleaning up afterwards.

The number of armed supporters Thaksin could possess in Thailand to actually fight a “civil war” are minimal. Of the 10,000-30,000 supporters he is able to mobilize with cash payments and bus services at any given time, only about 1,000 could be considered fanatical, and out of that, fewer still who are of military age, willing, and physically able to take up arms against Thaksin’s enemies. Thaksin had clearly augmented this with professional mercenaries, drawn from paramilitary border units in the north and northeast, but these numbered only about 300 and were easily outmatched by the Thai military in 2010.

Thaksin’s grip on the nation’s police forces allows him to produce on demand thousands from across his north and northeast political stronghold, but even if these police were armed, they lack the training, organizational skills, and coordination to pose any threat to the nation’s armed forces. They have proven in recent weeks to be completely ineffectual (and in some cases unwilling) against even unarmed protesters.

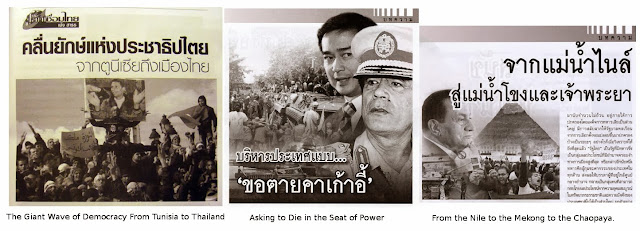

Image: From Thaksin Shinawatra’s “red” publications, left to right – “The Giant Wave of Democracy From Tunisia to Thailand,” “Asking to Die in the Seat of Power,” and “From the Nile to the Mekong, to the Chaopaya,” all indicate that Thaksin’s propagandists were likewise channeling the US State Department’s “Arab Spring” rhetoric as well as making the implicit threat that armed militancy was (and may still be) a desired option.

….

The real threat would be an influx of Cambodian mercenaries, trained, armed, and directed from Cambodia, and sent into Thailand covertly to be staged and deployed at key points during Thaksin’s continued bid to cling to power. These could be used to augment police and small units of fanatics drawn from Thaksin’s “red shirt” mob, or in individual operations aimed at various elements of the opposition.

This follows the same model Thaksin’s foreign backers are using against Syria, where armed militants had been prepared and staged along Syria’s borders, years before violence erupted in 2011. While initial reports from Western media claimed Syria was engaged in a “civil war,” it is now abundantly clear it was instead a foreign invasion by mercenaries sponsored by a conglomerate of NATO and Persian Gulf nations.

However, unlike in Syria, Thailand commands tactical, strategic, economic, and numerical superiority over Cambodia. There are few if any regional mechanisms that would protect the regime in Cambodia from retaliation by Thailand should violence break out and Hun Sen found complicit in supplying mercenaries and/or material support.

The Thai “civil war” Western analysts have long been predicting with poorly masked enthusiasm, would most likely only materialize using the “Syrian-model” of covert invasion combined with a coordinated propaganda campaign already being carried out by the Western media. Instead of Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and northern Iraq feeding militants into Syria, this new war would consist of Cambodia feeding militants and material in through northeast Thailand, with the resulting conflict appearing to be between “Thaksin’s political stronghold” there and the rest of the country.

However, the best Thaksin Shinawatra and his backers could hope to achieve in the wake of their eventual ousting from Thailand’s political landscape is wide-scale terrorism, not all out “war,” in hope of scaring off the military from larger scale operations to counter him. However, such violence would only open the door to hard-lined Egypt-style purges of Thaksin’s political allies and remaining financial assets inside the country, and the permanent exile of anyone in his regime smart enough to leave before the violence began. For Thaksin it would be a futile act of spite, but one the nation should be prepared for nonetheless.

Secession and “civil war” in Thailand are impossible. Thailand is not divided. If anything, now more than ever it is united in purpose against an increasingly destructive, perpetually self-serving regime that has long since overstayed its welcome. Thais of all kinds are eager to get back to the business of moving the nation forward and that the regime would threaten this desire with warnings of protracted “civil war,” is but another reason it must be uprooted permanently from Thailand’s political landscape.