The War Against “Plain Packaging”: Big Tobacco’s Current Battle

Like the mining industry, seemingly spawned from the same temperament of exploitation, the tobacco industry has been remorseless in its efforts to recover ground in the face of indignation on the part of health advocates. Diminishing profit margins, and stricter health regulations, have gotten the legal sections of tobacco companies shrill with activity and memorandum drafting. Arbitrators are being sought; international experts on treaty law are being solicited.

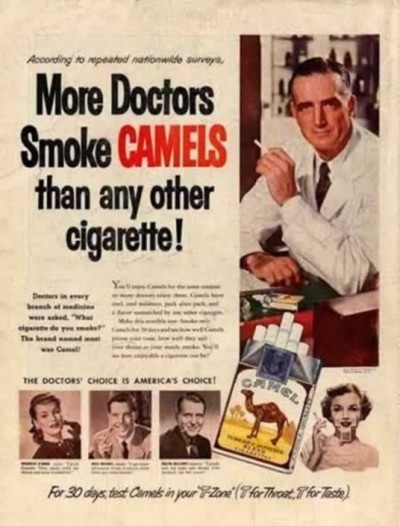

While their products kill, monsters of the smoking scape, such as Philip Morris International, British American Tobacco and Imperial Tobacco, have been attempting to beat every measure on cigarette packaging they can. The great bogeyman here is that of plain packaging, a measure that has been shown to dramatically reduce the enticements of smoking.

While Australia has drunk from the chalice of neo-liberal madness in the last two decades, its regulatory punch when it comes to the cigarette industry has tended to be an intrusive exception. The Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011 (TPPA), the first of its kind, was introduced to implement various obligations under the World Health Organisation (WHO) Framework on Tobacco Control (FCTC) while achieving one fundamental aim: discouraging and causing a cessation of smoking altogether.

The vital feature to the entire legislation lay in its emphasis on plain packaging, while also adorning them with images of imminent, carcinogenic doom. Such images resemble a form of violent, life-ending pornorgraphy: deformed children, rotting teeth, a patient on a hospital dead drawing his last, painful breath. While the strategy is furiously hard hitting, it has been shown to work in reducing smoking, despite fears it provides a “mystique” to smoking.[1]

The nature of the legislation was such as to trigger the interest of other countries keen to dispute the extent of its operation on the tobacco industry, notably in the area of trademarks. Between March 2012 and September 2013, Ukraine, Honduras, the Dominican Republic, Cuba and Indonesia commenced WTO dispute proceedings over the effect of Australia’s legislation.[2] Up to 40 countries expressed an interest in the proceedings, and sought to be joined.

The spirit of Ukraine’s protest here lay in supposed infringements by the TPPA legislation, and its associate components, with the agreement on Trade-Related aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS), and the agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT). The issue of public health, it should be noted, was of little concern. IP issues, however, were another matter. (To date, the WTO panel of consultant countries has been constituted, with the chair of the panel to issue a final report on the parties’ disputes “not before the first half of 2016”.[3])

The Australian government, even as it naively negotiates the secret Trans-Pacific Partnership Agreement in blithe ignorance of Washington’s corporate friendly agenda, should realise the effect a tobacco company can have in rattling the sovereignty, and domestic prerogative, of a government. Philip Morris may end up losing in its arbitration battles, but the toxicity of such challenges, not merely to the health of individuals, but that of sovereignty, should be noted.

Philip Morris Asia campaigned with some ferocity against the TPPA legislation, claiming that plain packaging constituted “an expropriation of its Australian investments in breach of Article 6 of the Hong Kong Agreement.”[4] The company also cited a lack of fair and equitable treatment as a result of the stringent packaging laws.

The Hong Kong agreement in question had been made in 1993 to promote and protect investments of Australia and Hong Kong, though the result was a sweet gift for corporations feeling the pinch from government regulations. Any policy that could shrink the profit margin was potentially the subject of legal attack, one which would enable the company to be the recipient of compensation. Such attacks tend to be conducted with gagging secrecy, another symptom of ailing democracy before the wiles of the tobacco lobby.

The umbrella of legal disputation of Philip Morris is a broad one. The next area of contest regarding cigarette packaging laws concerns Uruguay, significant for having reduced smoking between 2005 and 2011 by an annual rate of 4.3 per cent. In 2006, introduced laws specified that cigarette makers had to cover their packs with a generous 50 per cent spread of health warnings – or graphic pictograms. In 2009, the government got more adventurous, raising that level to 80 per cent.[5] Variation in a single brand sold was also prohibited – no “gold” or “light” types of a single product, the rationale here being that such wording seduces the purchaser into believing the item is less abrasive on health.

The company is using a similar formula there as with Australia, resorting to treaty law, specifically a trade agreement between Uruguay and Switzerland from 1991. The nature of this challenge verges on the grotesque – a well-moneyed corporate giant with the conscionable awareness of a plunderer, and a country whose gross domestic product is paltry in comparison. (To ease the financial burden of mounting legal fees, former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg has been forthcoming with some cash.)

The grounds between the challenges are virtually identical as well – the supposed violation of intellectual property rights. Making the company cover their packs with such warnings pushes the protected trademarks into oblivion, though the argument remains fanciful at best.

Tobacco companies are waging what seems to be a losing battle between health regulators on the one hand, and making the sale on the other. But they do have their supporters, notably those making money off the sale of cigarettes, directly or otherwise. In Britain, a coachload of East Lancashire newsagents is heading to Westminster to gripe about the lost custom that will ensue from an end to branded cigarette packing.[6] The vote on plain tobacco packaging is slated to take place before the general election.

The international trend, however, favours hard hitting messages to quit lighting up. Regulations have passed from as far field as Kenya, whose Tobacco Control Regulations 2014 mandate that all tobacco products shall not carry “a name, brand name, text, trademark or pictorials or any representation or sign which suggests that the tobacco product is less harmful to health rather than other tobacco.”[7] A new European Commission directive, which requires approval by MEPs and health ministers, will require almost 75 per cent of the packaging to feature the health consequences of smoking.[8]

Despite this concerted legislative battering, the tobacco industry has proven resilient before the chorusing warnings of health enthusiasts. The casualties in this war, already colossal, will continue to mount.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]

Notes:

[1]http://www.burytimes.co.uk/

[2]http://www.aph.gov.au/

[3] http://www.wto.org/english/

[4] http://www.ag.gov.au/

[5] http://www.npr.org/blogs/

[6] http://www.blackburncitizen.

[7] http://www.capitalfm.co.ke/

[8] http://www.thejournal.ie/do-