The Power of Fantasy: Bioterrorism, ISIS and Ebola Mania

Does demagoguery have an inventive side? Only if you assume semi-literacy is virtuous, and that imagination lies in the name of the manipulative. The combination of both Ebola and terrorism are the evil twins of the same security dilemma. It is manufactured. It is a confection. And it is, at the end, worthless in what it actually suggests. The effects of it are, however, dangerous. They suggest that politicians can be skimpy with the evidence yet credible in the vote.

Historically, disease and culture share the same bed of significance. Notions of purity prevail in these considerations. Bioterrorism has become, rather appropriately, another mutation in the debate on how foreign fighters arriving in a country might behave. Individuals such as Jim Carafano, vice president of the Kathryn and Shelby Cullom Davis Institute for National Security and Foreign Policy at the Heritage Foundation, continue insisting on the need for presidential administrations to form a “national bioterrorism watch system”.

“While [Ebola] is a dangerous disease that Washington needs to take seriously,” writes David Inserra of The Daily Signal, “America could face an even greater medical threat in the future: the threat of bioterrorism.”[1] While the language here seems to draw distinctions – that those suffering Ebola pose one set of problems, while the use of a bioterrorist agent is another – the ease of placing the two side by side is virtually irresistible.

In the wake of the Ebola outbreak, that old horse of potential bioterrorism has emerged with a convenient vengeance. This is not surprising, given the spectre of WMD fantasies that captivated the Bush administration in 2003. It is not sufficient that there are terrorists with a low probability of waging actual attacks on home soil, be they returning citizens, or simply foreign fighters wishing to stir up a good deal of fuss. Throwing in the disease component is hard to resist.

Rep. Mike Jelly of Pennsylvania decided to direct the bioterror genie the way of Islamic State fighters, suggesting that returning jihadists might cause Washington a good deal of headaches, not merely by their radicalisation, but by carrying the virus as a strategic weapon of infliction. “Think about the job they could do, the harm they could inflict on the American people by bringing this deadly disease into our cities, into schools, into our towns, and into our homes. Horrible, horrible.”[2]

This exotic lunacy was also appealing to Republican Rep. Joe Wilson of South Carolina, who even suggested that Hamas fighters might be daft enough to infect themselves with Ebola and make a journey to freedom land in order to engage in acts of infectious mayhem. Their venue of safe passage would be from the South, where the evils of an open border with Mexico risk allowing a dangerous pathogen into the country. Now that, dear readers, is exactly what such figures think about Mexico.

The moral calculus operating with Wilson is that of irrational, dangerous death – those who “value death more than you value life”. Those with such a creed are bound to get up to any old and lethal mischief. “It would promote their creed. And all of this could be avoided by sealing the border, thoroughly. C’mon, this is the 21st century.”[3]

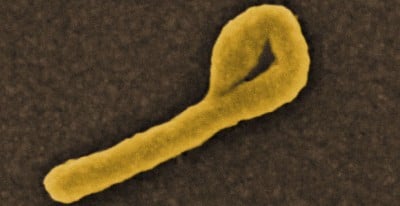

As to whether the idea of using such an agent would be feasible is quite something else. Weaponising such a pathogen has proven to be a formidable challenge. Such groups as the Aum Shinrikyo cult attempted to collect the virus while ostensibly on a medical mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was a failure of some magnitude. As Dina Fine Maron argues, the “financial and logistical challenges of transforming Ebola into a tool of bioterror makes the concern seem overblown – at least as far as widespread devastation is concerned.”[4] Even the FBI’s James Corney suggests that evidence of Islamic State’s involvement in an Ebola program is highly dubious.

This tends to get away from that old problem that the biggest of trouble makers in the business of death remain states rather than non-state ideologues. States have done more than their fair share of dabbling in the business of rearing microbes of death in the armoury. Be it small pox, botulism, and tularaemia, these have found their way into inventories and laboratories with disturbing normality.

Much of this has also been allowed to get away because of the Obama administration’s open confusion on the subject of how to handle the Ebola problem. The excitement has become feverish (dare one say pathological?) in the US, suggesting the double bind that the Obama administration finds itself. The President did not do himself any favours by on the one hand denying there was a grave threat, and then proceeding to appoint an “Ebola Czar” by the name of Ron Klain. This was classic bureaucracy in action – we create positions of unimportance to supposedly fight the unimportant, while admitting their gravity in creating such positions.

Certainly, the President found himself railroaded by events with the unilateral decisions of Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) and New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie (R) to implement mandatory 21-day quarantines for those returning from Ebola “hot zones”. This has always been the federal, and one might even say federalist headache: what is done in the White House and Washington often stays there. The response by states can often have a foreign sense to them. The US Centres for Disease and Control and Prevention has regarded such quarantine measures as unnecessary, but the CDC’s attempt to defuse the situation has not worked.

White House spokesman Josh Earnest had to face the music of disease on Monday, with a reporter suggesting that, if Klain was actually an “Ebola response coordinator”, it seemed “that you have a need for some coordinating here.”[5]

William Schaffner of Vanderbilt University, a long time student of infectious diseases, sees this as a matter of information, in so far as the more one gets, the less anxious one is bound to feel. “I would like not to call it irrational. When people are just learning about something, something that they regard as a threat, and they haven’t integrated all of this information still into their thought process, their sense of anxiety obviously increases.”[6]

Schaffner is unduly wedded to the rather unfashionable belief that knowledge somehow enlightens. But it is not knowledge that is driving this debate, but supposition. Facts are the enemy, and they continue to play the roles of silent, some might even say murdered witnesses.

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: bkampmark@gmail.com

Notes

[1] http://dailysignal.com/2014/

[2]http://www.buzzfeed.com/

[3] http://www.buzzfeed.com/

[4] http://www.scientificamerican.

[5] http://thehill.com/policy/

[6]http://www.theaustralian.com.