The Popular Uprising in East Ukraine. Rebellion against the First Neo-Fascist Regime in Post-War Europe

This week the war in East Ukraine continued, despite the referendums held in Donetsk and Lugansk on Sunday. In the circumstances, the referenda were well organised. The degree of accuracy of the returned result is questionable, but it is now beyond reasonable doubt that the rebel’s stand against the Kiev regime enjoys wide support in the region.

The Ukrainian regime has labelled the rebels as terrorists. At the same time, they have recruited black-clad irregular battalions of right wing volunteers and sent them into the Donbass. These ‘men in black’, whose existence even the mainstream media doesn’t deny, (see also kyivpost.com), are partly financed by big business interests close to the regime. Last week they killed civilians in Mariupol and Slavyansk.

In the lead-up to the referendum the mainstream media made a big point about the referendum being held at ‘gun-point’. They were right. In Krasnoarmeisk an armed pro-Kiev group tried to stop people voting. Shots were fired and some civilians were injured. The action had no military logic. There is no reason why the regime should have singled out this particular voting station in this particular town. It was almost certainly an act of pure terrorist bravado, designed to intimidate the voters and carried out by a rogue pro-regime brigade.

Welcome to the new Ukraine, the first neo-Fascist regime in post-war Europe.

The Regime, and its backers in the ‘Atlanticist bloc’ (Washington, the EU, NATO) and the mainstream media, have made much about the Donbass rebels being Russian agents. They still insist on characterising the rebellion as ‘pro-Russian’. Maybe this works with those who are ignorant of the considerable Russian ethno-cultural element in the Ukraine. RT recently featured an entertaining piece which showed that the likelihood that an American supported the Ukrainian regime was proportional to the probability they would be unable to locate Ukraine on a map.

But if the rebellion is just a ‘pro-Russian’ thing, then why is it happening at this very moment – in 2014. Why didn’t it happen in 2004? Obviously, there is something else going on here.

Where is the evidence that the ‘little green men’ are Russian? Real evidence that is, not photographs lifted from an instagram account and doctored to make two different men with equally bushy beards look like the same man in two different places. If real, hard evidence was available, it would have been plastered all over the front pages. The fact that is hasn’t been tells you all you need to know.

The Ukrainian regime and its backers claim the rebels are ‘terrorists’. The Interior Minister Avakov recently wrote on his Facebook page that “The only position towards terrorists is shoot to kill”. Strange, coming from the Interior Minister of a regime that came to power in questionable circumstances. Wasn’t there just the slightest hint of ‘terrorism’ in the daily, pre-organised and armed assaults on police and security forces carried out by extreme right wing groups around the Maidan in February 2014?

Yanukovych eventually made multiple concessions to the Maidan movement and concluded a peace deal. The current regime won’t negotiate at all. Not with ‘terrorists’. Their answer is to arm the most right-wing elements from the Maidan and unleash them on the citizens of East Ukraine.

The Russians, the OSCE and the German Foreign Ministry have all expressed the view that the regime has to enter into negotiations with the rebels. After all, we all now know – despite the lies of the Ukrainain regime and the Atlanticist bloc – that the rebels enjoy considerable support in their region. Despite that, the regime won’t budge from its position, and continues to wage war against Ukrainian citizens.

So leaving aside the simplistic propaganda about ‘Russian agents’ and ‘terrorists’, it’s time to look at the real reasons for the popular uprising in East Ukraine.

The Background

The current State of Ukraine is a relatively recent and arguably artificial political entity that incorporates regions with very different cultural norms and historical experiences. Broadly, there are four regions: The West, whose core is the Oblasts of Galicia, Ternopil and Volhynia. The Centre, based on Kiev and the Dnieper. The South, which includes Odessa and Dnipropetrovsk, and the East, which is essentially the Donbass and Kharkov.

Actually the current residents of Ukraine have only co-existed in a single unified polity since 1939 (leaving to one side the complex history of Crimea and some other small border regions).

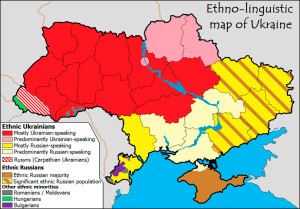

Western and Central Ukraine, including Kiev, is mainly Ukrainian speaking. Eastern Ukraine is mainly Russian speaking, as are most urban areas in the South. Most Ukrainian speakers are ethnic Ukrainians. About 65% of Russian speakers are ethnic Russians. Crimea, now a part of Russia, is ethnically and linguistically overwhelmingly Russian.

In parallel with the ethnic and linguistic distinctions, there are religious variations too. Ethnic Ukrainians tend to belong to either the Ukrainian Catholic Church (concentrated heavily in the West) or the Kiev Patriarchate Ukrainian Orthodox church. Ethnic Russians tend to belong to the Moscow Patriarchate Orthodox Church.

Many West Ukrainians, and increasing numbers of Kievan/Central Ukrainians, are strong supporters of an aspirational nationalism born of a sense of frustrated historical destiny. Classical Ukrainian nationalism traces its roots to the beginning of the last century. Like most European nationalist movements, it is big on enemies – those groups who threaten or oppress the nation, denying its manifest destiny. For Ukrainain nationalists, these have included the Jews, the Poles and the Russians. In the current political climate, Ukrainian nationalists are in denial about the anti-Semitic element in classical Ukrainian nationalism, but it is a simple matter of historical record. The anti-Polish element has also been very strong in the past.

The ideological enemy of Ukrainian nationalism is communism which is seen as a cover for ethnic Russian hegemony. Bitter resentment is felt towards the Russians, who are seen as responsible for the terrible suffering of the Ukrainian peasantry during the forced agricultural collectivisations of the 30’s, when millions starved to death.

Ethnic Russians in the Ukraine have a completely different sense of identity. They identify as part of a pan-Russian ethno-cultural space, and are mainly descended from two extended waves of settlement. The first was the creation of Novorossiya as a result of Imperial Russian expansion at the end of the 18th century. The second was the creation of the Soviet Union. Ethnic Russians are not typically anti-communist – in fact, East Ukraine is something of a communist redoubt within the former Soviet space.

In addition there are large numbers of Russian speaking Ukrainians. These are ethnic Ukrainians who became socialised into the Russian language in the context of industrial urbanisation. This is because in areas where Russian predominates it has always been more common in the cities than in the country.

These two basic ethno-linguistic groups (there are other groups, but these are now relatively small and do not impact the issue in question) have very different shared historical memories. This tends to reinforce both intra-group solidarity and extra-group exclusivity.

What could be called ‘Ukrainian ethno-culture’ memorialises the awful suffering during the Soviet(seen as Russian) forced collectivisations. This is used as the primary historical justification for the collaboration of many West Ukrainian nationalists with the Nazis. However, this collaboration was not without problems, as the German Nazis had nothing but contempt for the Slavic races, and merely sought to exploit anti-Russian feeling for their own purposes.

On the other hand, what could be called ‘Russian ethno-culture’ memorialises the appaling genocide at the hands of the Nazi invaders and their collaborators, and the eventual victory of the Red Army. Many more inhabitants of the Ukraine fought for the Red Army than fought against it, but due to the current political ascendancy of Ukrainian nationalism, this balance is not reflected in much contemporary historical re-imagining.

Ethnic Ukrainians are more likely to vote for a centre-right, bourgeois liberal or Western-oriented political party. Ethnic Russians are more likely to vote for a centre-left, statist or Eurasian-oriented political party. Nationalist parties have very little support among Russians. Communist parties have very little support among Ukrainians.

The two ‘ethno-cultures’ have internalised historical narratives that are potentially mutually antagonistic. For one group, the enemy is the Russians(Soviets) and the heroes are the Ukrainian nationalists who fought the Russians(Soviets) during the Second World War. For the other, the enemy is the Nazis, together with the Ukrainian nationalists who either fought with the Nazis or fought against the Soviets, and the heroes are the Soviets – ethnic Ukrainian and ethnic Russian.

In a pluralist and inclusive political culture, these sorts of differences need not be a problem, as long as the groups are able to construct their sense of identity in a mutually respectful manner.

Unfortunately, in contemporary Ukraine there has been a pronounced rise of virulent, identitarian ethno-nationalism amongst self-identifying ‘Ukrainians’. These nationalists forcefully reject the ‘Russian’ aspect of Ukraine’s civil and political identity. They regard Russia as the enemy, and are at best distrusful of ethnic Russians in the Ukraine. They also resent the widespread use of Russian language, and the historical and cultural remnants of Soviet Communism.

The resulting clash of ethno-cultural narratives and historio-political identities can be exemplified in the ‘battle of the monuments’. In recent years monuments to Stepan Bandera have sprung up all over Western Ukraine. Monuments to Lenin are now entirely concentrated in the East and South of Ukraine. There was one in Kiev, but it was torn down as part of the Maidan rising. For many in the East, Bandera was a criminal and a collaborator and Fascist. For many in the West, Lenin was a criminal and precursor of the Stalinist collectivisations. He was also a Russian.

It must be emphasised that Ukraine has managed to hold together for eighty years despite these differences. But the unity of the Ukrainian Nation is now under severe stress.

The Maidan and the Nationalist Coup

The Maidan rising, and the subsequent coup against the Yanukovych regime, was heralded by the Atlanticist bloc and mainstream media as the victory of democratic and liberal forces against a corrupt, statist and pro-Russian regime.

This is the standard narrative that Atlanticists use to ‘colour’ a revolution in which a victory for the non-government side would be in the geopolitical interests of the Atlanticist bloc. As will be shown, in the Ukraine, as in Syria, it is more lies than truth.

The Atlanticist narrative also hides another critical fact. The Maidan movement and post-coup regime are largely the creation of just one of the two broad ethno-cultural and political groups that cohabit in the Ukraine. This is a very important when trying to understand the response of many in the East and South to recent events.

The Maidan protest movement was overwhelmingly driven by Ukrainian nationalist sentiment, and by protestors who were mainly from Western and Central Ukraine. The regime that it spawned is a coalition of three political parties. The geographic centre of gravity of all three parties is in the West/Central Ukraine, with a smaller presence in the South (especially Dnipropetrovsk), but very attenuated support in the East.

One of the parties, the Fascist Svoboda (on which, more below), is almost exclusively based in the West. In the 2012 Rada elections, the Fascist Svoboda could barely conjure up 1-2% of the vote among the millions of voters in the industrial Russian-speaking East. Yet they got up to 30% of the vote in West Ukrainian cities like Ternopil and Lyviv.

The anti-Russian nature of a significant element in the new post-Maidan regime was evident from the very start. Voices were heard calling for the recognition of Ukrainian as the sole official language, Russian pages were taken down from government web sites, Russian television stations were blocked and Russian journalists were denied visas.

In Kiev, Russophobic fascists were openly running around attacking opponents – for example sacking the offices of the Party of Regions and the Communist Party, and attacking television journalists who were ‘off-message’ on Crimea.

As if this wasn’t enough, in the light of the historical background outlined above, it is difficult to understate the offence caused to the Russian speaking and socialist industrial working class of the Donbass region, when they realised that a coup they had played no part in had installed a regime including West Ukrainian fascists.

Did the one-sided ethno-cultural nature of the Maidan protest and the regime it spawned cause any concern for its Atlanticist backers – the USA, EU and NATO, those stout defenders of pluralism and inclusiveness? Not a bit. Why? Because their sole interest was in exploiting the situation for geopolitical gain. It was all about winning Ukraine for the Atlanticist bloc, deepening the engagement with NATO, extending the EU corporatist oligarchy, standing up another debtor state for the IMF, and stuffing it to Putin for wrecking their schemes to vaporize Ba’athist Syria and make the Middle East a little bit safer for the USA, EU, NATO and Israel – the self-ascribed ‘international community’.

In pursuit of this goal not only did the Atlanticist bloc treat the Russian speaking, socialist-leaning East as if it didn’t exist, but it showed itself willing to work openly with Fascists.

The Atlanticist bloc had to cover-up the fact that it had ridden roughshod over the delicate divisions in Ukraine in order to score a geopolitical victory, jeopardising the very fabric of pluralist (as opposed to ethno-nationalist) Ukrainian unity. It had to explain why so many in the East, South and Crimea began to protest in large numbers, many of them waving Russian flags as a sign of their offended sense of ethno-cultural identity.

So the Atlanticist bloc has spun and sustained a hysterical and utterly disingenuous anti-Russian conspiracy narrative, hoping thereby to deflect public opinion from the fact that the divisions in contemporary Ukraine have been largely provoked by a run of events shamelessly exploited by the Atlanticist bloc for its own gain.

For example, according to the Atlanticist spin, Crimea did not secede – it was invaded. It was all a Russian land grab. Of course this conveniently ignores the fact that by every conceivable norm of democratic national self-determination – so favoured of the Atlanticist bloc when geopolitically convenient – Crimea always was, is, and should be Russian.

Crimea had only been handed to the Ukraine in 1954. It had always maintained and nurtured a strong Russian identity. Support for reunion with Russia was overwhelming.

Why did it secede in March 2014? Why not any time earlier? Why not in 2004? The reason is because the events in Kiev provoked a genuine and completely understandable irredentist backlash. For the Crimea, the deal with ‘Ukraine’, concluded in 1954 without her consent, was now well and truly over. Ethnically Russian Crimea had no interest in being part of an Atlanticist proxy Ukrainian nationalist regime. Particularly one that contained Fascists.

As for the ground-swell of anti-regime opinion in the East, especially the Donbass, it is also a purely reflexive phenomenon. There were no ‘little green men’ before the ‘men in black’ seized power and treated the Russophile East with Russophobic contempt.

In Kiev, members of the Rada have been openly threatening for months to ban the Communist Party and the Party of Regions. This kind of anti-democratic nonsense has just started up again following the Donetsk referendum, largely because elements in the Party of Regions and the Communist Party have had the temerity to lay the blame for events in the Donbass exactly where it belongs – at the feet of the post-coup regime and its international sponsors.

But there is an even more important aspect to this. The nature of the Donetsk rebellion has been systematically distorted. It is consistently characterised as ‘pro-Russian’ or ‘separatist’. In fact, at a popular level, it is primarily anti-Fascist. Anyone who has seen pictures of the banners and posters draped over the barricades around occupied buildings or roadblocks, or seen the banners carried in demonstrations, or heard the chants of ‘Fashisty’ aimed at the invading Ukrainian forces in Mariupol or Slavyansk, cannot fail to have noticed this.

So why do the people of the Donbass regard the regime as Fascist? Isn’t this just Russian propaganda exploiting historical fears?

Ukrainian Fascism – from Movement to Regime

On February 21st, the Yanukovych regime concluded a peace deal with the three major parties that provided the Rada-based political leadership for the Maidan protest. The deal was brokered by Germany, France and Poland. The deal was made after the violence that caused over a hundred deaths, and included a commitment to a government of national unity, early elections, full amnesty for all protestors, and a full and open investigation, under the leadership of the EU, into the multiple deaths that had occurred in the previous three days.

If the deal had been honoured, there is every possibility that Ukraine would be in a very different place today. The reason it wasn’t honoured is very simple – when the Rada leadership took it to the hard-core element in the Maidan, they vehemently rejected it and launched further violent attacks on regime targets. The following day, Yanuokovych disappeared, supposedly fearing for his life (and probably for his money). The Party of Regions imploded, and the old regime was ‘impeached’ in dubiously constitutional circumstances.

The driving force behind this was the radical element on the Maidan, by now mobilised around the leadership of the notorious Pravy Sektor – a fascist group. This is a regime that was brought to power by Fascist violence. At this time Russia’s position was the absolutely correct one of insisting on a return to the February 21st agreement. The USA refused to countenance this, and gave 100% backing to the new post-coup regime, completely ignoring the multi-lateral peace deal that had been trashed by the Maidan.

But there is much more to the Fascist presence in the current regime than the circumstances surrounding the coup.

Rewind to 1991, to the foundation of the Social National Party. As any student of Fascism knows, ‘Social Nationalism’ is just ‘National Socialism’ with the predicate/object relationship inverted to sound less frightening. The meaning is the same.

Social Nationalism = National Socialism = Nazism = Fascism

The Social National Party was a party inspired by historical Nazism and its connections with wartime radical West Ukrainian nationalism. They had connections with football hooligans. They operated a paramilitary organisation, called the Patriots of Ukraine, led by one of the co-founders of the party, a certain Andriy Parubiy. Membership of the party was limited to ethnic Ukrainians.

Amazingly, the current incarnation of this party is in government in the Ukraine. And Andriy Parubiy is the head of National Security in this government. A government which enjoys the full support of the USA, EU, NATO and the mainstream media.

In 2004 the Social National Party changed its name to Svoboda, and abandoned the now riskily obvious crypto-runic symbol that it had sported as a fascist emblem since its early skinhead days.

In that same year the leader, Oleh Tyahnybok, who during the Maidan rising basked in the spotlight of media respectability with the likes of Catherine Ashton and John McCain, made a speech at the graveside of a former commander of the collaborationist Ukrainian Insurgent Army. His speech called on Ukrainians to fight the ‘Muscovite Jewish Mafia’ and lauded the collaborationist Organisation of Ukrainian Nationalists for having fought ‘Muscovites, Germans, Jews and other scum who wanted to take away our Ukrainian state’. This is a matter of public record and caused considerable controversy in the Ukraine of 2004.

At the time of the Orange Revolution, the party were insignificant, but during the latter half of the decade they experienced considerable growth, especially in West Ukraine. This should be seen in the context of the overall growth of the pan-European far right – organisations like Jobbik in Hungary, the FN in France and the BNP in the UK. In 2009 Svoboda joined the Alliance of European National Movements as an observer member, and its members rubbed shoulders (and raised arms) with Fascists from Italy, Hungary, Spain and Portugal.

In 2009 Svoboda also enjoyed its first major electoral breakthrough, winning over 30% of the vote in the Ternopil Oblast elections. In 2010, it became a major force in Galicia, and in 2012, in the Rada elections, it won 38 seats, gaining just over 10% of the national vote and multiplying its share of the vote fourteenfold compared to 2007.

In Western Ukraine Svoboda’s share of the vote was as high as 40%, but in the East it failed to get more than 2%.

During the 2012 election Svoboda entered into an electoral agreement with the Yatsenyuk/Tymoschenko Batkivshchyna Party (no anti-fascist cordon sanitaire in the Ukraine). After the election Svoboda entered into agreements in the Rada with the Yatsenyuk led party as well as UDAR, the party led by Vitali Klitschko. These same three parties formed the Rada leadership of the Maidan movement and form the current regime.

The shocking truth is that if 2004 was the Orange Revolution, then 2014 was the Brown Revolution.

The difference between 2004 and 2014 is the renaissance of West Ukrainian Fascism in the intervening decade. This has led to the open participation of fascists in a government regime for the first time in post-war European history. This happened with the full support of the Atlanticist bloc, and in alliance with an anti-leftist coalition of bourgeois nationalists and neo-liberals. Svoboda currently have 5 members in the government of Ukraine.

The Donbass , where in 2012 there had been roughly 20 Communist votes for every Fascist vote, found itself ruled by a post-coup regime containing Russophobic and deeply anti-communist Western Fascists.

There is a further element of the fascist scene in Ukraine that has enjoyed a spectacular street-level renaissance in the last 6 months – the notorious Pravy Sektor. Pravy Sektor were formed from an association of various fascist paramilitary groups, including the Patriots of Ukraine, ditched by Svoboda when it decided to court the mainstream in 2004.

Pravy Sektor became the decisive street level force during the Maidan rising, and led the final push to eject the Yanukovych regime after the Maidan rejected the multi-lateral peace deal. Pravy Sektor also plays a significant part in providing volunteers for the new regime’s secretive irregular armed battalions. It’s well armed, and recently re-located its leadership from Kiev to Dnipropetrovsk for the express purpose of being closer to the ‘action’ in the Donbass.

The mainstream media have attempted to portray the Maidan coup and the subsequent regime as another ‘colour revolution’ – part of the gradual but ineluctable victory of bourgeois liberal capitalism in the spaces formerly occupied by the Soviet bloc. But there is as much brown to this revolution as orange. It is an absolute scandal that the USA, EU and NATO, together with their cheerleaders in the mainstream media, are aiding and abetting a regime that is arming and turning loose fascist wing-nuts on the industrial, working class heartlands of the country.

Civil War?

This is the real background to the Donbass rebellion, and it explains not only why it is happening but why it is happening now.

The Ukrainian regime is a neo-fascist regime that came to power as a result of a violent coup perpetrated by right-wing, nationalist forces. The Crimea and Donbass rose up against this unconstitutional usurpation of state power.

The Atlanticist bloc gave full support to the coup, and expected Russia to obediently bow to it’s self-declared right to global hegemony. Putin had different ideas. The Crimea seceded and re-joined Russia .

The Ukraine, supported by the Atlanticist bloc, has armed fascist groups and unleashed them against the Donbass. This has only made matters worse, and at the referendum the people of the Donbass made their views clear for all to see.