The New Silk Road, A Chinese-style “New Deal”. The Economic and Geopolitical Consequences

Historians will remember that the Chinese President Xi Jinping officially launched the new “Silk Road” with a 30 minute speech at the Boao Economic Conference on Hainan Island the 28 March 2015, in front of 16 heads of State or government and 100 or so ministers from the 65 countries which are on the path, land or sea, of this new trade route[1]. For us, involved in political anticipation, what a challenge we have been given! China is suggesting that we imagine the future by stepping back several centuries, even two millennia.

Such a move isn’t absurd, as a fact ! The strength of nations such as Russia, Iran, India or China comes from their ability to think far into the future. Europe also has an historical depth – the two world wars encouraged it to rediscover the age before nations, that of Charlemagne or even the Roman Empire. This way of thinking is probably most alien to the US undoubtedly and which will look at the Chinese project with the greatest suspicion. However it will have to live with reality: the appetite for this “resurrection of the past” from their European allies, but also a country like Israel[2], all countries which have just decided to join the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank created by China for the occasion, confirms that this project which is based on an ancient past has a future.

In what follows, we propose sketching the foreseeable consequences of the Chinese initiative. Three elements must be identified more clearly: do we say “the road and corridor” of Chinese power? What will be the repercussions on the rest of Eurasia? What will be the US attitude, facing what represents the first challenge of a new era, where it’s going to have to learn that power is shared.

65 countries, 4.4 billion people, 63% of the global population are affected by the New Silk Road. For the moment, these countries together only account for 29% of world output, but we are only at the beginning of a global rebalancing around Eurasia. China expects that, within 10 years, its trade relations with the countries along what it calls “the road and corridor” should have more than doubled to $2.5 trillion. China has sent a very strong signal: at a time when its economic growth has begun to slow, China hasn’t chosen to stimulate its economy through military spending, which would justify a possible “Cold War” with the US[3]. It has chosen diplomacy and trade with a view to rebalancing: to depend less on the transatlantic economic relationship it seems to it that it must strengthen various relationships “in the West”. It’s a matter of literally once again becoming “The Middle Kingdom” [4].

To gather together the capital necessary for this new economic axis’ gigantesque infrastructure, China has launched the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, with 52 participating countries, including the nine leading European economies. The initial capital was originally intended to be $100 billion but, given the influx of applications, it will be higher. China has already made it known that, to attract investments, no right of veto would be given to the Board of Directors (unlike the US in the Bretton Woods financial institutions). However, let’s not be under any illusion, China, drawing on its diplomatic experience since time immemorial, will find all sorts of indirect means to control to control a public investment bank for which it took the initiative[5].

The country intends to take advantage of a favourable situation to advance its interests: Russia needs its support if it wants to stand firm in the showdown with the US over the Ukraine’s future. And the EU is seriously tempted by increased Chinese investment in Europe to contribute to an exit from the crisis[6].

However, don’t overestimate China’s position of strength either. Having accumulated huge dollar reserves, it feels, given the US economy’s fragility, the need to diversify its assets. Investing part of its currency reserves in a major project such as the “New Silk Road” matches a need. On the other hand in the diplomatic power struggle which puts it against the US, Russia isn’t totally dependent on China: not only can it count on its nuclear deterrent but also on the support, direct or indirect, of India, Iran and Turkey. Finally, carefully note that China is financial power is far from sufficient to meet investment needs spanning two continents and four seas. The « road and corridor» project will only succeed to the extent that each regional group invests massively[7]. From the EU perspective this already raises the question of knowing what will follow the Juncker Plan. The European Investment Bank and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development will play an increasing role in the coming years to enable Europe to play its part in the “New Silk Road”.

The EU is at a crossroads. The Ukrainian crisis becomes a handicap if it continues: not only do the economic sanctions imposed on Russia negatively affect the European economy, but an increasing number of investment opportunities are being lost in central Asia, and the Union itself risks being divided between an Atlantist camp and one eager to come to an arrangement with Russia. To tell the truth there is no other way than reinforcing the Minsk agreements. And, to avoid an endless crisis, Germany will gradually give substance to a European pillar of the Atlantic Alliance, strong enough to influence the US and lead it to the crisis’ exits. The way in which the European countries have converged on the Asian Infrastructure and Investment Bank confirms that a rebalancing towards Eurasia from the transatlantic link – the European equivalent of the Chinese move from the transpacific link towards the “New Silk Road” could take place quickly.

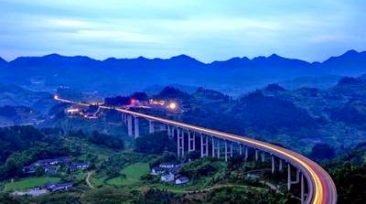

Figure 1 – China’s New Silk Road – Chinese projects for a modern economic zone – land route in brown; sea route in blue. Source : Die Welt

The map that unfolds in front of our eyes is fascinating for an historian accustomed to think like Fernand Braudel, an historian of the Mediterranean and capitalism, with a “long-term” approach: from a Chinese point of view the land route leaves from Xi’an, passing through Bishkek, Tashkent, Teheran, Ankara, Moscow, Minsk before reaching Rotterdam, Anvers, Berne and Venice.

The ancient City of the Doges is at the western end of a maritime route through Athens, Cairo, Djibouti, Nairobi, Colombo, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore (with a branch towards Jakarta), Hanoi, Hong Kong and Fuzhou ending at Hangzhou. China is therefore offering us a tie-up with a 2000 year old trade route; it’s also proposing, in contrast to Huntington’s fatalistic vision, a true dialogue of civilizations between the Confucian, Indian, Persian, Turkish, Arabic, East African, Christian Orthodox and Western zones of influence.

Players in a polycentric globalization, the heirs of the Chinese Empires, Mongolian, Persian, Russian, Ottoman, Arab, Byzantine, Romano-Germanic, French and British have the fascinating opportunity to finally live a common and peaceful history. Care should be taken, for Eurasia’s balance, that India should be increasingly sought and better integrated in these new networks than China is currently planning. France and Germany, with the rest of the European Union, has a natural card to play here, also important from the point of view of their long-term interests: this “New Silk Road” will only be beneficial for all the countries concerned to the extent that it will be based on a balance of forces. The rapprochement with India is a valuable advantage to weigh against Russia and China. Additionally, it allows it to stay more in line with the BRICS rationale, a rationale to which the Silk Road doesn’t belong at the moment, at a time when Chinese dynamism and the Russian need to neutralize US influence in Central Asia leads to favouring The Shanghai Cooperation Organization.

The Chinese “New Silk Road” project is made possible by the new organizational age of which the Internet is one of the most striking manifestations. The Chinese leaders have undoubtedly understood faster than their European counterparts that the information revolution has exploded the old geopolitical opposition between the continental and maritime powers.

Crossed by high-speed trains, called to depend less and less on its energy resources’ geographic concentration, Eurasia is in the process of becoming a “liquid space”[8]. The New Silk Road can, without exaggeration, be considered as a double “liquid” axis falling under the same criteria of analysis. Obviously, such a development will have its shadowy areas. The “liquid spaces” could be infested with pirates – already numerous on the Internet. Pepe Escobar of the Asia Times online has, for a long time, called the “liquid war”[9] the way in which the US contributed to the destruction of States like Iraq, Libya or the Ukraine. However, let’s measure the change underway and the immense changes on the horizon for the European Union, whose mission is no longer to build this “small promontory of the Asian landmass” which Paul Valéry spoke of, but to organize a triple interface: Euro-Atlantic, Euro-African and Eurasian….

Notes

[1] Source : Die Welt, 30/03/2015

[2] Source : Japan Times, 01/04/2015

[3] Whilst in 2010, China had decided to begin reducing its military spending (source: Wikipedia), the tensions between the West and the emerging nations, expressed in 2014 by the Ukrainian crisis, nevertheless led it to

increase it by 12.2% last year with 10% announced for 2015. That said, as a percentage of GDP, which is the method habitually chosen for measuring a country’s military spending (remember that the US asks NATO members to contribute up to 2% of their GDP to the Alliance’s budget), the share of this spending is more or less stable – around 2.1% (the US spends more than 4%) – taking account of the fact that China’s GDP is increasing by nearly 7% this year. Something else seems to say that China is increasing its military spending as reasonably as possible and it’s the fact that, in the context of its opening to the world, it’s forced to be more transparent and that a whole host of hidden spending is undoubtedly simply in the process of emerging into the open. But the total budget for military spending doesn’t peak at only 95€ billion, versus 460€ billion for the US, knowing that this sum is largely devoted to maintaining a huge military personnel (2.1 million), and that the share devoted to equipment purchase is all the more reduced(source : Deutsche Welle, 04/03/2015).

These factors lead our team to consider that, contrary to what the Western media would have us believe, China doesn’t have an aggressive military posture.

[4] Michel Aglietta/ Guo Bai, La voie chinoise. Capitalisme et empire, Paris, Odile Jacob, 2012

[5] François Godement, Que veut la Chine ?, Paris, Odile Jacob, 2012

[6] Claude Meyer, La Chine banquier du monde, Fayard, Paris, 2014

[7] Source : Eurasia Review, 30/03/2015

[8] I have borrowed this concept from John Urry, Global complexity, 2000

[9] Pepe Escobar, Globalistan : How the Globalised World is Dissolving into Liquid War, 2007