The Naked Class Politics of Ebola

Just as a glass prism differentiates sunlight into its component colours, corresponding to the different wavelengths, the Ebola crisis ravaging three West African countries has produced three distinct responses, corresponding to the three principal classes of capitalist society.

Ebola is a disease caused by a virus, that is to say, a natural phenomenon. But that is only a small part of the story. Ebola is also an epidemic, and the causes and conditions of the epidemic are social, economic, and political rather than natural. Outside of these social and economic conditions, the disease would have been contained or even eliminated long before now. The Ebola catastrophe is as much a product of the global capitalist crisis as are the carnage in Syria and Iraq, the housing shortage in New Zealand, and racist cop murders in the United States, and the solution to it is just as much a question of the class struggle.

For four centuries West Africa was plundered of its human resources, in the form of the slave trade. Entire kingdoms and cultures were shackled to the hunger of the European powers for slaves, others were ground to dust by the incessant slave raiding. Alongside this came the plunder of the region’s natural resources. The lands along the Gulf of Guinea were called the Grain Coast, Ivory Coast, Gold Coast and Slave Coast – countries named not for the peoples who inhabited them but the commodities which they supplied to the conquering powers. (Côte d’Ivoire retains the name to this day, though its great elephant herds have been reduced to a tiny remnant). Whatever railways, roads and infrastructure the colonial powers built were for the purpose of speeding the extraction of these commodities.

Through the surge of freedom struggles following the Second World War, these countries threw off the shackles of colonial political rule – and in the process produced some of the finest thinkers and fighters the world has ever known. But the economic exploitation didn’t let up for a minute. Nigerian oil, Liberian rubber, Ivorian cocoa, Guinean bauxite still flowed to markets in the former colonial powers, principally France, Britain, and the United States* (and more recently, to China and India) at rock-bottom prices dictated by the buyer.

To the extent that modern industry has developed, such as the oil industry in Nigeria, it has been at a colossal environmental and human cost. The Niger River delta, a rainforest, wetland and mangrove area with exceptionally high biodiversity, where Nigeria’s oil industry is centred, has been degraded by decades of easily preventable oil spills, the drinking water, farmland, fisheries of its thirty million people poisoned.

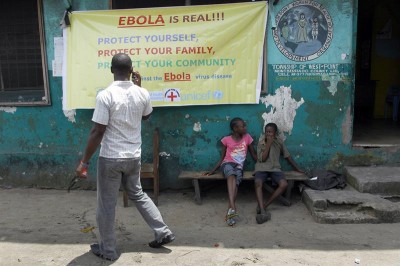

The three countries at the centre of the Ebola epidemic are among the most impoverished in the world. The permanent legacy of centuries of uninterrupted plunder is chronic and widespread malnutrition, dirt roads, poor or non-existent sanitation, unreliable or non-existent electric power, and one doctor per 100,000 inhabitants. These are the conditions in which an Ebola outbreak becomes an epidemic. “Before the outbreak, Liberia’s only lab capable of testing blood for highly infectious diseases was the Liberian Institute on Biomedical Research—a compound of World War II-era buildings and rusted cages that used to house chimpanzee test subjects. The bat-infested facility could only process 40 blood specimens a day and the electricity only worked intermittently,” the Wall Street Journal reported. “Bomi’s Liberia Government Hospital hasn’t had a working X-ray machine since the machine’s processor ‘blew up’ two years ago. The hospital had to shut for a month after its first Ebola case appeared in June.”

However, Ebola does not present a major threat to the continued extraction of Africa’s natural wealth. Thus, the bourgeois response to the epidemic has been notable for its numb indifference to the death and suffering, and its consequent economic dislocations.

For several months after the existence of Ebola was confirmed in the three countries of West Africa, the world bourgeoisie did nothing to assist them to combat the disease and prevent it from spreading. On the contrary, their first actions were to withdraw such minimal assistance schemes that were operating. In July the United States withdrew all its Peace Corps volunteers from the three countries, including those engaged in health education programs – at the very time when health education programs were urgently needed.

The burden of providing trained medical personnel was left to a handful of charities, especially Doctors Without Borders (Médecins Sans Frontières).

The Australian government publicly announced their refusal to send medical personnel into the region. “We aren’t going to send Australian doctors and nurses into harm’s way without being absolutely confident that all of the risks are being properly managed. And at the moment we cannot be confident that that is the case,”Prime Minister Tony Abbot said. The government of Israel took a similar stance.

In August British Airways suspended flights to Liberia and Sierra Leone against the protests of those governments. Christopher Stokes, director of Médecins Sans Frontières in Brussels, added: “Airlines have shut down many flights and the unintended consequence has been to slow and hamper the relief effort, paradoxically increasing the risk of this epidemic spreading across countries in west Africa first, then potentially elsewhere. We have to stop Ebola at source and this means we have to be able to go there.”

The bourgeois response became a lot noisier when the first cases of Ebola were diagnosed in the imperialist countries, but the isolationist character of the response remained the same: protecting those unaffected at the expense of those most affected or directly threatened by the epidemic.

Liberian man, Thomas Eric Duncan, who developed symptoms in the US six days after arriving from Liberia, was treated as a hostile vector of contagion rather than a human being in need of treatment. Dallas County prosecutor publicly discussed laying criminal charges against Duncan if he should survive. The prosecutor’s spokesperson Debbie Denmon said, “If he ends up being on his deathbed, it would be inhumane to file charges,’ she said. ‘It’s a delicate situation.” Duncan later died.

Under increasing pressure to be seen to be doing something, some imperialist governments began announcing aid packages, mostly limited to money and equipment, and chiding each other for not doing enough. US President Barack Obama declared it to be a “security crisis” – not a health crisis – and promised troops, making it clear they would stay well away from any person who might be infected with the disease. One month later, not one of the 17 special tent-based treatment centers promised by the US is yet operational.

By mid-October, with the crisis growing daily, only a tiny proportion of the money and equipment promised had been delivered. Médecins Sans Frontières spokesperson Christopher Stokes said it was “ridiculous” that volunteers working for his charity were bearing the brunt of care in the worst-affected countries. MSF runs about 700 out of the 1,000 beds available in treatment facilities Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, according to the BBC. Above all, it was trained medical personnel that was needed – labor – and the bourgeoisie, while it commands vast resources of labor in capitalist industry, came up well short of the need in that regard. “Money and materials are important, but those two things alone cannot stop Ebola virus transmission,” Dr Margaret Chan, director-general at the World Health Organization, said last month. “Human resources are clearly our most important need.”

If the bourgeois response to the Ebola crisis has been one of indifference, the response of the petty-bourgeoisie has been marked by panic and unscientific speculation. The petty-bourgeoisie is a dependent class, beholden to the big bourgeoisie for its privileges, yet in constant fear of being cast down into the working class, and hence wracked by insecurities.

Panic in the face of this threat has been consciously whipped up in big-business press coverage and statements by the authorities. For example, Anthony Banbury, chief of the UN’s Ebola mission, said in early October that “there is a chance the deadly virus could mutate to become infectious through the air.”

Such claims have no scientific foundation. While viruses do evolve and mutate, no human virus has ever been known to change its mode of transmission. Alarmist predictions and speculations such as this are an attempt to frighten the bourgeoisie into taking action on the epidemic.

Having lost any connection to verifiable fact, the natural extension of such speculations is into the realm of conspiracy theories. The Liberian Daily Observer newspaper ran an article by Liberian-American academic Dr Cyril Broderick claiming that the Ebola outbreak in West Africa was deliberately initiated by US military medical researchers who were experimenting on the virus as a possible biological weapon.

In another speculation that wraps several fears into one, Forbes Magazine reported Al Shimkus, a Professor of National Security Affairs at the U.S. Naval War College, as saying that “the Islamic State may already be thinking of using Ebola as a low-tech weapon of bio-terror,” raising the fear that IS members might infect themselves and then deliberately spread the disease to others.

Broderick’s speculation is not totally implausible. The US military and public health authorities, including the Centre for Disease Control which is prominently involved in the Ebola response, have a proven record of carrying out clinical trials and medical experiments on unknowing human subjects, especially Black people, including one where people in Guatemala were deliberately infected with syphilis without their knowledge. The poisonous legacy of these government crimes has not been forgotten, nor should it ever be. Broderick’s conspiracy theory rests on the fully justified distrust of these institutions, which runs deepest among people of African descent.

But none of these speculations and conspiracy theories is backed up by any verifiable evidence; they remain purely speculative and, like all speculations, essentially idle. By focusing attention on the question “what if,” they become yet another obstacle to facing the known facts of the situation, the urgent question of what is.

The meeting-point of the bourgeois and petty-bourgeois responses to the Ebola crisis, where inaction masquerading as “taking action” combines with anti-scientific irrationalism, must undoubtedly be the policies adopted by the US and UK to carry out body-temperature screening at the airport for passengers arriving from West Africa. Given the nature of the Ebola condition, the fact that symptoms can take up to 21 days after the date of infection to appear, and then strike rapidly and severely, such border checks could not possibly prevent more than a tiny fraction of infected travelers from crossing a border. At the same time, they will inevitably “catch” great numbers of people with body temperatures raised for other reasons, thereby diverting resources further from where they are needed. David Mabey, professor of communicable diseases at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, said “the screening was a complete waste of time.”

The working class has only its labor to contribute, yet that labor is the key to solving the crisis. The proletarian response to the Ebola crisis is exemplified by the unselfish actions of the West African health workers, who are carrying out the socially necessary tasks of caring for the patients, collecting and burying bodies, and educating the population in prevention and containment measures. They do this despite inadequate safety equipment, serious threats to their own health, inadequate pay, and despite sometimes being ostracized in their own communities. The shortages of medical personnel are being overcome by dozens of volunteers.

A Guardian report on the “Ebola burial boys” of Sierra Leone describes the situation: “One morning, residents in Kailahun [Sierra Leone] woke up to find their only bank closed. Those with cars fled. Life did slowly pick up again, but a state of emergency in July shut down schools. Soldiers poured in to quarantine entire communities and, in these lush farming hills, trade slowed to a trickle.”

In desperation, 20 young men signed up for the burial teams, each paid $100 (£61) a month for the task. ‘Hunger is killing more people than Ebola,’ said Abraham Kamara, 21, a fellow digger. They work to rigorous standards enforced by the Red Cross, but pay a heavy price.

“When I’m passing, people I know say, ‘don’t come near me’!” Jusson said. He looked skyward for a moment before continuing: “I try to explain to them. If we don’t volunteer to do this, there’ll be nobody to bury the dead bodies because all of us will be infected.”

The proletariat is an international class; its watchword is solidarity. Solidarity differs from aid. Solidarity means tying one’s fate to that of the people you are aiding. Given the real personal dangers to the health of those caring for Ebola patients, no matter how careful they are, this distinction is crucial to understanding the different international responses. Solidarity and isolationism are opposites.

In stark contrast to the response of the imperialist world has been the outstanding solidarity offered by the one country where the working class hold state power: Cuba. When the call went out for volunteer health workers to go to West Africa, fifteen thousand experienced health workers stepped forward, living proof of Che Guevara’s statement: “to be a revolutionary doctor, there must first be a revolution.” This is in a country of 11 million people, under extreme economic pressure from the US blockade, a country which already has 50,000 health workers serving overseas in 66 countries.

103 nurses and 62 doctors selected from among the 15,000 arrived in Sierra Leone in early October, a further 296 will go to Guinea and Liberia shortly. The Cuban government has indicated its willingness to send still more personnel, provided there is enough funding and infrastructure to support them.

This commitment has many precedents. The Cuban people – a large proportion of who are descended from African slaves – made a similar commitment to Africa by sending volunteers to defend newly-independent Angola from attack by apartheid South Africa in 1975. (Recently declassified documents have revealed that the US Secretary of State at the time, Henry Kissinger, was so incensed by this that he drew up plans to ‘smash Cuba’ with airstrikes in response.)

Nelson Mandela said of Cuba’s action in Angola, “It was in prison when I first heard of the massive assistance that the Cuban internationalist forces provided to the people of Angola, on such a scale that one hesitated to believe; when the Angolans came under combined attack of South African, CIA-financed FNLA, mercenary, UNITA, and Zairean troops in 1975.”

“We in Africa are used to being victims of countries wanting to carve up our territory or subvert our sovereignty. It is unparalleled in African history to have another people rise to the defense of one of us.”

“We know also that this was a popular action in Cuba. We are aware that those who fought and died in Angola were only a small proportion of those who volunteered. For the Cuban people internationalism is not merely a word but something that we have seen practiced to the benefit of large sections of humankind.”

Asked about the dangers involved in volunteering to join the medical mission in Sierra Leone, Julio César Gómez Ramírez, a nurse who is going to West Africa with the brigade said, “I’m not afraid. We’ve been taught to help others. Like many of my compañeros, I participated in the war in Angola, and we risked our lives there. This isn’t more difficult.”

On several occasions during this crisis the health workers in Liberia, Nigeria, and elsewhere have engaged in strikes to demand adequate safety protection while they carry out their perilous tasks, and to demand payment of unpaid wages and adequate compensation for the dangers involved in their work. These struggles are an essential part of advancing the fight against the disease.

A lesson from history is relevant here. A hundred years ago and more, tuberculosis was a killer disease afflicting workers in the advanced capitalist countries in Europe and elsewhere. It is commonly believed that the scourge of tuberculosis was overcome (at least in the imperialist countries) by the development of antibiotic vaccines and cures. This is false. Long before the antibiotics were widely used, death rates from tuberculosis had been steadily decreasing. By the time the antibiotics were widely used in the post-World-War-2 world, 90% of the decline in tuberculosis mortality had already been achieved. The reduction had taken place as a consequence of working class struggles for decent housing and higher wages – and consequently, better nutrition.

Today the working class is rapidly growing and strengthening in West Africa. Powered chiefly by oil exploitation in Nigeria, Ghana, and offshore developments in several regions along the Gulf of Guinea including Liberia, a process of social transformation is underway. This is bringing into being the class that has the power to drive back Ebola and all the social and economic conditions that gave rise to it.

* Footnote: The United States is a former colonial power in West Africa. The state of Liberia was founded as a settler-colony for former slaves who wanted to return to Africa. The “Americos” in Liberia formed a distinct social layer in Liberia, who held, up to 1980, a monopoly on political power. Liberia still has strong commercial ties with the United States today.

James Robb, a communist at large living in New Zealand, blogs at convincing reasons.