The Malvinas: An Unresolved Dispute

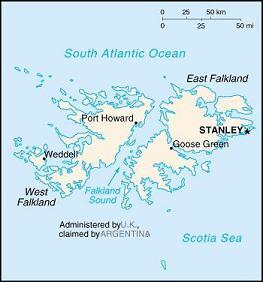

The question of the Malvinas Islands (Falkland Islands) remains one of those unresolved disputes in international politics which seldom receives much attention from the world community. This is a pity since the United Nations has for the last 50 years called upon the two parties to the dispute — Argentina and Britain — to negotiate a peaceful solution through bilateral negotiations.

The call from the UN is embodied in a General Assembly Resolution — Resolution 2065 (XX) — adopted on the 16th of December 1965. It invites the Governments of Argentina and Britain “to proceed without delay with the negotiations recommended by the Special Committee on the Situation with regard to the implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples with a view to finding a peaceful solution to the problem, bearing in mind the provisions and objectives of the Charter of the United Nations and of General Assembly resolution 1514(XV) and the interests of the population of the Falkland Islands ( Malvinas).”

Argentina has all along expressed a readiness to negotiate. Initially, Britain had also agreed to open talks on the dispute. Its Foreign Secretary, on a visit to Argentina in January 1966, expressed this view. In paving the way for bilateral negotiations the two governments agreed to cooperate on specific matters related to air and maritime services, and postal and telegraphic communications.

However, London made negotiations on the dispute difficult when it embarked upon exploration of natural resources in the Malvinas, thus contravening the spirit of the UN Resolution. This forced the UN General Assembly to adopt yet another Resolution — Resolution 31/49 — in December 1976 requesting both parties to the dispute “to refrain from adopting decisions that entail the introduction of unilateral modifications to the situation while the islands are going through the process recommended” by UN Resolutions. 102 states voted in favour of the Resolution, 1 (Britain) voted against it while 32 abstained. Britain ignored the stand of the vast majority of nation-states.

It was partly because of British intransigence that the military junta ruling Argentina at that time decided to invade the Malvinas in April 1982 to re-assert Argentinian sovereignty over the islands. It is of course true that the transfer of power from one military dictator to another, economic stagnation and a degree of civil unrest in Argentina were even more prominent factors in the decision to go to war. Argentina’s defeat in the 10 week war emboldened the British elite to strengthen its grip upon the Malvinas. London was even less prepared now to negotiate with Buenos Aries.

But the UN has stood by its decision that there must be direct bilateral negotiations between the two countries to find a peaceful solution to the territorial dispute. The UN does not recognize any British claim to suzerainty over the Malvinas and the surrounding islands. Regional groupings in Latin America and the Caribbean such as ALBA and CELAC also support the Argentinian position. So do most of the non-aligned nations who regard British control over the Malvinas as a vestige of the colonial era. Argentina for its part has since 1994 incorporated its claim of sovereignty over the Malvinas into its national constitution.

What civil society should do is to endorse the UN call for negotiations. Many more civil society voices should be raised on behalf of bilateral talks as the only feasible way of finding a peaceful solution to a dispute that goes back to the early decades of the 18th century. Civil society groups in Britain in particular should speak up. They have a moral responsibility to do so.

Dr. Chandra Muzaffar is President of the International Movement for a Just World (JUST).