The Iraq War Ten Years Later: Declassified Documents Show Failed Intelligence, Policy Ad Hockery, Propaganda-Driven Decision-Making

National Security Archive Publishes "Essential" Primary Sources on Operation Iraqi Freedom

Of relevance to recent developments in Iraq, this article was first posted on GR in March 2013.

We might add to this dossier of propaganda and manipulation the fact amply documented that ISIS is a terrorist entity supported and financed by the Western military alliance.

National Security Archive Briefing Book No. 418

March 19, 2013

Edited by Joyce Battle and Malcolm Byrne

The U.S. invasion of Iraq turned out to be a textbook case of flawed assumptions, wrong-headed intelligence, propaganda manipulation, and administrative ad hockery, according to the National Security Archive’s briefing book of declassified documents posted today to mark the 10thanniversary of the war.

The Archive’s documentary primer includes the famous Downing Street memo (“intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy”), the POLO STEP PowerPoint invasion plans (assuming out of existence any possible insurgency), an FBI interview with Saddam Hussein in captivity (he said he lied about weapons of mass destruction to keep Iran guessing and deterred), and the infamous National Intelligence Estimate about Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction (wrong in its findings, but with every noted dissent turning out to be accurate).

“These dozen documents provide essential reading for anyone trying to understand the Iraq war,” remarked Joyce Battle, Archive senior analyst who is compiling a definitive reference collection of declassified documents on the Iraq War. “At a moment when the public is debating the costs and consequences of the U.S. invasion, these primary sources refresh the memory and ground the discussion with contemporary evidence.”

|

A decade after the U.S. invasion of Iraq (March 19, 2003), the debate continues over whether the United States truly believed that Iraq’s supposed WMD capabilities posed an imminent danger, and whether the results of the engagement have been worth the high costs to both countries. To mark the 10 th anniversary of the start of hostilities, the National Security Archive has posted a selection of essential historical documents framing the key elements of one of America’s most significant foreign policy choices of recent times. The records elucidate the decision to go to war, to administer a post-invasion Iraq, and to sell the idea to Congress, the media, and the public at large.

The Archive has followed the U.S. role in the war since its inception and has filed hundreds of Freedom of Information Act requests for declassification of the underlying record. As the government releases these records, the Archive regularly makes them available on its Web site. In the near future, a significant collection of freshly declassified materials will appear as part of the “Digital National Security Archive” collection through the academic publisher ProQuest. (In the shorter term, visitors may visit our new Iraq War page for a compilation of currently available declassified materials on the subject.)

The first item is a memo from the State Department’s Near East bureau, provided to incoming Secretary of State Colin Powell at the very outset of the new George W. Bush administration in 2001, outlining the Clinton administration’s policy supporting regime change in Iraq, but through financial and weapons support for internal opposition groups, propaganda efforts, and regional actors rather than direct action by the U.S. military. (The Iraq Liberation Act signed by Bill Clinton on October 31, 1998, codified this policy and committed the U.S. to continuing support for Iraqi opposition groups.)

A bullet-pointed set of notes discussed by Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld with Gen. Tommy Franks, head of the U.S. Central Command, in late 2001 shows the Pentagon already diverting focus and energy from the Afghan campaign less than three months after the U.S. and its allies entered that country. An “Eyes Only” British government memo succinctly summarizes the climate leading to war by the summer of 2002: the U.S. saw military action as inevitable; George Bush wanted military action to be justified by linking Iraq to terrorism and WMD; to that end “intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy,” while as to discussion in Washington of the aftermath of invasion, “There was little…”

U.S. military planning proceeded frantically throughout 2002, with Secretary Rumsfeld pushing hard for readiness for invasion before the end of the year, as the myriad power point slides the Pentagon generated demonstrate (a set of which is included here). A full-bore public relations campaign underway at the same time ramped up a climate of anticipation and even fear, with Vice President Cheney telling U.S. military veterans that the U.S. would need to use “every tool” for a threat lurking in more than 60 countries, declaring flatly that Iraq was actively pursuing offensive nuclear weapons, possessed weapons of mass destruction, and was planning their use against friends of America and the U.S. itself. The CIA leadership participated with evident eagerness, providing Congress and the public with glossy illustrated reports hyping the Iraqi threat and abandoning all standards of prudence in its characterizations of the alleged Iraqi threat.

The PR blitz won enthusiastic support from many in the right wing and from liberal hawks supporting military intervention on human rights grounds. Perhaps most aggressive was the famous neoconservative Iraq lobby, whose Project for a New American Century had begun campaigning for U.S. direct military action against Iraq in the 1990s. This public relations campaign probably reached its apex with Colin Powell’s February 2003 illustrated speech before the U.N., received by many as a masterful demonstration of the case for war and by only a few as a web of unverified suppositions. Meanwhile, as one of Secretary Rumsfeld’s famous “snowflake” memos from October 2002 shows, top rungs of the administration were well aware of the potential risks of an invasion, yet they chose to go forward without fully considering their implications.

The documents show that misconceptions about Iraq were useful to the Bush administration as enablers for the decision to invade; they also help account for calamitous U.S. policies post-invasion. The administration had high hopes for Iraq’s oil resources, as myriad planning documents show. Among other expectations, the oil sector was to be back in operation within a few months and with its revenues the Iraqi people were expected to pay for their country’s own invasion and reconstruction under U.S. authority.

|

George Bush, somehow not briefed by his advisors to expect divisions within Iraq, non-conventional warfare, and a nationalism-fueled resistance declared “major combat operations” over on May 1, 2003 – some eight years before his successor finally withdrew the bulk of U.S. forces from the country. Iraq’s post-invasion destabilization was vastly intensified by U.S. policies, including the imposition of Coalition Provisional Authority Orders 1 and 2, which overturned the country’s civil and military infrastructure, abruptly deprived hundreds of thousands of any prospects for an income, and replaced the old system, degenerate as it was, with something approaching chaos.

In Iraq, the U.S. would get its man – capturing Saddam Hussein in his “spider hole” in December 2003 – as would happen several years later with Osama bin Laden, an actual planner of the 9/11 attacks and the main focus of U.S. enmity until the Bush administration re-directed its energy to Saddam Hussein. Given the opportunity to explain his policies, Saddam only confirmed what most students of international relations or Iraq’s history would have already known: that Iraq’s leadership felt itself vulnerable to enemies near and far, with the perceived Iranian threat never far from mind, and believed that an attempt to maintain ambiguity about its weapons capabilities, conventional and non-conventional, was a necessary part of its defensive posture.

The last documents in this compilation are look-backs at some of the things that went wrong. One is an excerpt from the comprehensive Duelfer report on Iraqi WMD provided to the U.S. director of central intelligence, the other is a “mea culpa” by the CIA for not recognizing that there was no WMD program worthy of the name at the time of the invasion. These records are in no way a last word on the war, whose ramifications will plague the U.S. no less than Iraq for decades to come, but they (especially the Duelfer report) do convey attempts to use hard evidence rather than relying heavily on supposition to summarize Iraqi policies in regard to weapons of mass destruction. The Duelfer report attributes grand ambitions to Iraq’s leadership as an impetus for the country’s weapons policies, but describes a Saddam Hussein motivated largely by survival instincts and by rivalry with near neighbors – not by the aggressive intentions against the U.S. around which Washington created a justification for preemptive war.

The Iraq Primer: Key Documents on Operation Iraqi Freedom

Document 1: U.S. Central Command, “Desert Crossing Seminar: After Action Report,” June 28-30, 1999

Source: Freedom of Information Act

In late April 1999, the United States Central Command (CENTCOM), led by Marine General Anthony Zinni (ret.), conducted a series of war games known as Desert Crossing in order to assess potential outcomes of an invasion of Iraq aimed at unseating Saddam Hussein. Desert Crossing amounted to a feasibility study for part of the main war plan for Iraq – OPLAN 1003-98 – testing “worst case” and “most likely” scenarios of a post-war, post-Saddam, Iraq. This After Action Report was an interagency product assisted by the departments of defense and state, as well as the National Security Council, and the Central Intelligence Agency, among others. It presented recommendations for further planning regarding regime change in Iraq.

The report’s pessimistic conclusions in many ways closely paralleled events that actually occurred after Saddam was overthrown. It forewarned that regime change might cause regional instability by opening the doors to “rival forces bidding for power” which, in turn, could cause societal “fragmentation along religious and/or ethnic lines” and antagonize “aggressive neighbors.” Further, the report illuminated worries that secure borders and a restoration of civil order might not be enough to stabilize Iraq if the replacement government were perceived as weak, subservient to outside powers, or out of touch with other regional governments. An exit strategy, the report said, would also be complicated by differing visions for a post-Saddam Iraq among those involved in the conflict.

The Desert Crossing report was similarly pessimistic when discussing the nature of a new Iraqi government. If the U.S. were to establish a transitional government, it would likely encounter difficulty, some groups discussed, from a “period of widespread bloodshed in which various factions seek to eliminate their enemies.” The report stressed that the creation of a democratic government in Iraq was not feasible, but a new pluralistic Iraqi government which included nationalist leaders might be possible, suggesting that nationalist leaders were a stabilizing force. Moreover, the report suggested that the U.S. role be one in which it would assist Middle Eastern governments in creating the transitional government for Iraq.

Document 2a: U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs Information Memo from Edward S. Walker, Jr. to Colin Powell, “Origins of the Iraq Regime Change Policy,” January 23, 2001.

Source: Freedom of Information Act

Document 2b: U.S. Executive Office of the President, Office of the Press Secretary, “Statement by the President” attaching “Iraq Liberation Act” text, October 31, 1998.

Source: Freedom of Information Act

Just three days after President Bush’s inauguration, this memo informs the new secretary of state, Colin Powell, that the origin of the United States’ Iraq regime change policy is the Iraq Liberation Act of 1998, and provides several quotes from President Bill Clinton supporting concepts included in the act, but not a U.S. invasion. In the attached statement accompanying his signing of the Iraq Liberation Act, President Clinton indicates that the U.S. is giving Iraqi opposition groups $8 million dollars to assist them in unifying, cooperating, and articulating their message.

Document 3: U.S. Department of Defense, Notes from Donald Rumsfeld, [Iraq War Planning], November 27, 2001; Annotated.

Source: Freedom of Information Act

Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld used these notes to brief Central Command chief Gen. Tommy Franks during a visit to Tampa to discuss a new plan for war with Iraq. Rumsfeld prepared them in consultation with Paul Wolfowitz and Douglas Feith. They list steps Defense Department officials believed could lead to the collapse of the Iraqi government, and reflect elements of an existing plan developed with and for the Iraqi National Congress, including seizure of Iraq’s oil fields, protection of a provisional government, transfer of frozen Iraqi assets to said government, giving it Iraq’s oil revenues, and regime change. The notes list some triggers the administration could use to initiate war, including Iraqi military actions against the U.S.-protected enclave in northern Iraq, discovery of links between Saddam Hussein and 9/11 or recent anthrax attacks, and disputes over United Nations WMD inspections (“Start now thinking about inspection demands.”). They show that Rumsfeld wanted Franks to get ready to initiate military action before a full complement of U.S. forces were deployed to the region. A section in the notes on “radical ideas” was withheld from release. The notes include Feith’s point: “Unlike in Afghanistan, important to have ideas in advance about who would rule afterwards.” They conclude by calling for an “influence campaign” with a yet-to-be established start time.

Document 4: United Kingdom, Matthew Rycroft, Private Secretary to the Prime Minister, Cabinet Minutes of Discussion, S 195/02, July 23, 2002

Source: Printed in The Sunday Times, May 1, 2005, Downing Street Documents

These notes offer insight into the attitude of the Bush administration toward regime change, the U.N. approach, and propaganda efforts. The document contains the now-notorious statement in which Sir Richard Dearlove, chief of British foreign intelligence (“C”), reports from his talks in Washington: “There was a perceptible change in attitude. Military action was now seen as inevitable. Bush wanted to remove Saddam, through military action, justified by the conjunction between terrorism and WMD. But the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy.” Dearlove also reported that Bush’s “NSC has no patience with the UN route.” Admiral Sir Michael Boyce, chief of defense staff, then added a briefing on actual plans for an invasion, showing these to be far advanced at this date, before U.N. inspections were even accepted by all parties concerned. Foreign Secretary Jack Straw, noting “the case was thin,” argued for enlisting U.S. Secretary of State Colin Powell to persuade President Bush to back U.N. inspections, but he warned, “It seemed clear that Bush has made up his mind to take military action.”

Document 5: U.S. Central Command Slide Compilation, ca. August 15, 2002; Top Secret / Polo Step, Tab K [1003V Full Force – Force Disposition]

Source: Freedom of Information Act

Military plans for war with Iraq were repeatedly updated at Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld’s behest throughout 2002 and up to the March 2003 invasion. A series of declassified briefing slides document these planning revisions. Rumsfeld wanted the Iraq invasion to be an exemplar of modern technological warfare, so the troop levels recommended by planners for a successful invasion were downgraded over time during the planning phase in accordance with the secretary’s philosophy. In addition, the administration hoped for Turkish support for the invasion and included forces based in that country in its plans. These hopes were dashed when Turkey decided not to join the invasion, in accordance with overwhelming popular opinion.

This set of slides shows the administration’s optimism about its ability to achieve its objectives in Iraq: Phase IV, a term used for post-invasion operations, was, according to this set of slides, expected to last some three to four years as the U.S. troop presence declined to 5,000 personnel. The end game within this time frame was to lead to a “stable democratic Iraqi government” engaged in security cooperation with the U.S. In reality, the invasion led to a far more prolonged U.S. military presence, years of unanticipated violence, massive population displacement, the breakdown of Iraqi society on sectarian grounds, and the ultimate failure of the U.S. to achieve the cooperative military and intelligence partnership with Iraq’s government that it had anticipated as planning for the invasion was underway.

Document 6a: Director of Central Intelligence, National Intelligence Estimate, Iraq’s Continuing Programs for Weapons of Mass Destruction, October 2002. Top Secret [Excerpt].

Source: The White House

Document 6b: Director of Central Intelligence, National Intelligence Estimate, Iraq’s Continuing Programs for Weapons of Mass Destruction, October 2002. Unclassified version.

Source: CIA public release

Document 6c: United States Senate, Select Committee on Intelligence Report on the U.S. Intelligence Community’s Prewar Intelligence Assessments on Iraq. Released on July 7, 2004 [Excerpt].

Source: SSCI

There have been three separate releases of the famous October 2002 National Intelligence Estimate (NIE) on Iraq’s Continuing Programs for Weapons of Mass Destruction. The NIE concluded that Iraq continued its weapons of mass destruction programs despite U.N. resolutions and sanctions and that it was in possession of chemical and biological weapons as well as missiles with ranges exceeding U.N. imposed limits. In addition, it was judged that Iraq was reconstituting its nuclear weapons program and, if left unchecked, would probably have a nuclear weapon before the end of the decade – assuming it had to produce the fissile material indigenously. If Iraq could acquire sufficient fissile material from abroad it could construct a nuclear weapon within several months to a year, the estimate reported. The NIE also examined Iraq’s possible willingness to engage in terrorist strikes against the U.S. homeland and whether Saddam would assist al-Qaeda in conducting additional attacks on U.S. territory.

The released key judgments section is also notable for its reporting of dissents within the Intelligence Community on two related issues – when Iraq could acquire a nuclear weapon, and its motive in seeking to obtain high-strength aluminum tubes. The State Department’s Bureau of Intelligence Research (INR) argued that while Saddam wished to acquire a nuclear weapon, it did not believe that Iraq’s recent activities made a compelling case that a comprehensive attempt to acquire nuclear weapons was being made. INR, along with the Department of Energy, questioned whether the high-strength aluminum tubes Iraq had been attempting to acquire were well-suited for use in gas centrifuges used for uranium enrichment.

The Senate Intelligence Committee report also posted here contains a harsh critique of the intelligence community’s assessments on Iraq. In addition, the committee pointed out the CIA’s troubling decision to heavily redact the NIE including withholding embarrassing topics such as the ways the initial public portions of the estimate sharply misrepresented the intelligence community’s views by deleting caveats, hedged language and dissents in the underlying intelligence.

Document 7: Donald Rumsfeld, Snowflake, “An Illustrative List of Potential Problems to Be Considered and Addressed,” (“Parade of Horribles”), October 15, 2002

Source: The Rumsfeld Papers

Donald Rumsfeld wrote this list of setbacks to be anticipated from an Iraq invasion in the midst of the administration’s deliberations over whether to attack Iraq. The document is a so-called “snowflake,” one of a “blizzard” of short memos – some just a few words in length – that Rumsfeld sent to colleagues and subordinates in the government during his tenure at the Pentagon. Reportedly intended for President Bush, this one itemizes 29 potentially negative outcomes, several of which were highly prescient and show that top U.S. officials were aware of the serious risks involved when they made the decision to go forward with Operation Iraqi Freedom. For example, item 13 says, “US could fail to find WMD on the ground in Iraq and be unpersuasive to the world.” Item 14 reads, “There could be higher than expected collateral damage – Iraqi civilian deaths.” Point 17 notes that “US could fail to manage post-Saddam Hussein Iraq successfully …” while #19 predicts that “Rather than having the post-Saddam effort require 2 to 4 years, it could take 8 to 10 years, thereby absorbing US leadership, military and financial resources.”

Document 8: State Department, “The Future of Iraq Project,” Oil and Energy section, April 20, 2003.

Source: Freedom of Information Act

The “Future of Iraq Project” was a mammoth 13-volume State Department study obtained by the National Security Archive and others under the Freedom of Information Act. It was one of the most comprehensive U.S. government planning efforts for raising Iraq out of the ashes of combat and establishing a functioning democracy. To prepare the report, the Department organized over 200 Iraqi engineers, lawyers, businesspeople, doctors and other experts into 17 working groups to strategize on topics including the following: public health and humanitarian needs, transparency and anti-corruption, oil and energy, defense policy and institutions, transitional justice, democratic principles and procedures, local government, civil society capacity building, education, free media, water, agriculture and environment and economy and infrastructure.

One of the more optimistic sections dealt with oil and energy. The study understood that Iraq’s oil reserves represented “a tremendous asset which can be used to benefit every last citizen of the country, regardless of ethnicity or religious affiliation.” This enthusiasm was echoed by former Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz, who told the House Appropriations Committee on March 27, 2003, “We’re dealing with a country that can really finance its own reconstruction, and relatively soon.” However, the report underscored that Iraqis would not embrace the idea of having the Coalition run the country’s oil industry because “nationalism in Iraqi oil industry is very strong.”

Document 9a: Coalition Provisional Authority Order Number 1: “De-Ba’athification of Iraqi Society,” May 16, 2003.

Source: www.iraqcoalition.org

Document 9b: Coalition Provisional Authority Order Number 2: “Dissolution of Entities,” August 23, 2003.

Source: www.iraqcoalition.org

The responsibility for reviving and rebuilding Iraq fell largely to the Coalition Provisional Authority, headed by State Department official L. Paul Bremer from May 2003 to June 2004. The monumental task included everything from creating a representative government to reviving the economy to reforming the justice system to restoring basic public services. In hindsight, many observers have pointed to certain basic actions taken by Bremer as key miscalculations that led to critical problems in the rebuilding process. One was the order on the “De-Ba’athification of Iraqi Society (Order No. 1), which Bremer later said was based on the same principle as de-Nazification after World War II. Critics pointed out that the CPA carried out the process in a sweeping manner that took little account of individual cases and wound up alienating important segments of Iraqi society. Another such order was to dissolve a range of presidential, government and military entities including the army, the police and security forces (Order No. 2). Most observers agree that the effect of this order was to send a message to key elements of Iraqi society, whose efforts and support would be needed in the rebuilding of the country, that they were not going to be welcomed as a part of the process.

Document 10: Saddam Hussein Conversation with FBI Agent George Piro, June 11, 2004.

Source: Freedom of Information Act

After the capture of Saddam Hussein by U.S. troops in December 2003, FBI special agents carried out 20 formal interviews with the former Iraqi dictator and at least 5 “casual conversations,” according to once-secret FBI reports released through the Freedom of Information Act to the National Security Archive. The records of these fascinating encounters include historically valuable insights into Saddam’s thinking on a wide variety of topics from his sense of his relationship to the Iraqi people, to the catastrophic Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s. Even though Saddam knew he was speaking to an American interrogator, and may be expected to have slanted his comments accordingly, the materials represent significant resources for studying the ex-Iraqi leader and his rule over the country. In this excerpt, a “casual conversation” from June 2004, Saddam expounds on one of the main reasons for his dissembling about Iraq’s WMD capabilities to U.N. inspectors and the world: his fear of the threat emanating from Iran.

Document 11: “Comprehensive Report of the Special Advisor to the DCI on Iraq’s WMD,” with Addendums (Duelfer Report), April 2005 [Excerpt].

Source: CIA

Charles A. Duelfer, a Special Adviser to CIA Director George Tenet, prepared this report on Iraq’s weapons programs. It was completed in October 2004. His lengthy investigation concluded that most of Saddam Hussein’s secret programs had been destroyed as a result of the 1991 Persian Gulf war and later inspections by the United Nations. Contrary to assertions by senior former Bush administration officials, he found no evidence of “concerted efforts” by Iraq to restart the program. This applied to nuclear as well as to biological and chemical weapons. “We were almost all wrong,” Duelfer said later. The report stated that Saddam Hussein may have had it in mind to rebuild his capabilities but there was no organized effort or strategy to do so and in any case his interest was not to attack the U.S. but to build up Iraq’s image abroad and specifically to deter outside adversaries, primarily Iran.

Document 12: Central Intelligence Agency, Analysis, “Misreading Intentions: Iraq’s Reaction to Inspections Created Picture of Deception,” January 5, 2006

Source: Mandatory Declassification Review request to CIA

This CIA analysis of its own failure to realize that Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction program was non-existent is, along with other (public) records such as the Duelfer report and the Robb-Silberman report[1], part of the lessons-learned aspect of the Iraq experience for the United States. The assessment describes the intelligence community’s error (mirrored by other governments, to be sure) as the consequence of “analytic liabilities” and predispositions that kept analysts from seeing the issue “through an Iraqi prism.” Despite heavy redactions, the declassified version of the document reveals some striking comments. For example, on page 14, it reports, “Given Iraq’s extensive history of deception and only small changes in outward behavior, analysts did not spend adequate time examining the premise that the Iraqis had undergone a change in their behavior, and that what Iraq was saying by the end of 1995 was, for the most part, accurate.” On page 16, the authors add, “Analysts tended to focus on what was most important to us – the hunt for WMD – and less on what would be most important for a paranoid dictatorship to protect. Viewed through an Iraqi prism, their reputation, their security, their overall technological capabilities, and their status needed to be preserved. Deceptions were perpetrated and detected, but the reasons for those deceptions were misread.”

* * * *

Bonus: Key Public Speeches on the Iraq War

Document 1: Vice President Cheney’s Speech to the Veterans of Foreign wars, August 26, 2002

Source: Project for the New American Century

In a speech to American war veterans promoted by the neoconservative advocacy group the New American Century, Vice President Cheney says that in response to the 9/11 attacks the U.S. “has entered a struggle of years … against a new kind of enemy.” He says that the U.S. is facing “a global terror network” seeking weapons of mass destruction that “would not hesitate to use them against us.” Cheney says categorically that Baghdad has “been very busy enhancing its capabilities in the field of chemical and biological agents. And they continue to pursue the nuclear program they began so many years ago.” According to Cheney, Saddam Hussein wants WMD in order to dominate the entire Middle East, control a major chunk of world oil supplies, threaten America’s friends, and subject the U.S. to nuclear blackmail. Without equivocation, the vice president says that “there is no doubt that Saddam Hussein now has weapons of mass destruction.”

Cheney declares that in his response to Iraq President Bush will “proceed cautiously” and “consult widely,” then implies an analogy between Iraqi objectives and the attack on Pearl Harbor, which the U.S. failed to forestall, and cites a friendly source who predicts that Iraqis are “sure to erupt in joy” should the U.S. overthrow their government.

Cheney’s confident assertions were later proven wrong by unfolding events and by the evidence obtained, and seriously analyzed, during the U.S. occupation of Iraq.

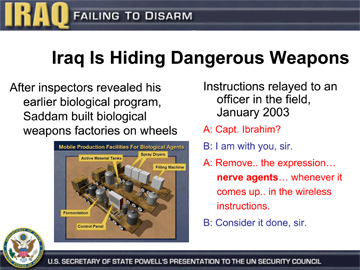

Document 2: Secretary of State Colin Powell, Speech to the United Nations, February 5, 2003 (and slide show).

Source: The White House

Secretary of State Colin Powell’s United Nations address in February 2003 is generally viewed as one of the Bush administration’s most effective public steps in winning media and public support for war. Discussing Iraq’s bio-weapons programs, he does not name the notorious informant CURVEBALL, but he cites an Iraqi defector whose “eye-witness account of these mobile production facilities has been corroborated by other sources.” Senior CIA officials, including then-Deputy Director for Operations James Pavitt and European operations chief Tyler Drumheller, reported later that they had previously raised objections to the use of CURVEBALL’s information, but were surprised to find, on the eve of Powell’s remarks, that the Iraqi source had resurfaced. Powell himself later lamented the speech. “Of course I regret that a lot of it turned out to be wrong,” he told The Daily Show host Jon Stewart, although he insisted that much of the intelligence was “on point” and that “we thought it was correct at the time.” (The Daily Show, June 12, 2012)

Document 3: Remarks by the President from the USS Abraham Lincoln At Sea Off the Coast of San Diego, California, May 1, 2003.

Source: The White House

On May 1, 2003, speaking from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, President Bush declared, “My fellow Americans: Major combat operations in Iraq have ended.” Commenting that “Iraq is free,” the president gave the impression that the most difficult part of the U.S.-led invasion was over. As virtually every observer and former participant has since acknowledged, the challenge of resuscitating the country and re-establishing order and a functioning economy and system of government was just beginning.

For more information contact: Joyce Battle or Malcolm Byrne 202/994-7000 or [email protected]