The Economics of America’s Private Prison System

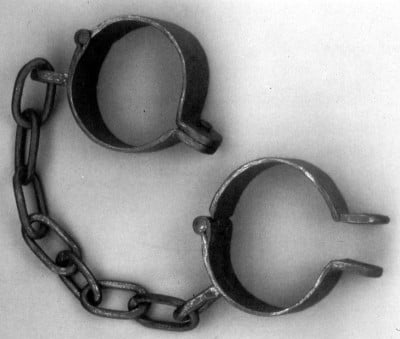

The Civil War Didn’t End Slavery After All

The American prison system is a massive — if invisible — part of our economy and social fabric.

Slavery has been abolished in the United States since 1865, when the 13th Amendment was passed in the ashes of the Civil War.

Well, almost abolished. Actually, the amendment included a caveat: “except as punishment for a crime.” Since then, prison and forced labor have always gone together.

In fact, with over 2 million people behind bars in this country, the American prison system is a massive — albeit largely invisible — part of our economy and social fabric.

Recent years have seen a rise in both private prisons and the use of prison labor by private, for-profit corporations. This has created perverse incentives to imprison people and exploit them for cheap labor — often at 50 cents an hour or less.

Corporations such as Microsoft, Target, Revlon, and Boeing have all made products with prison labor. With over a third of home appliances and 30 percent of speakers and headphones made using prison labor, it’s likely most American households own inmate-made products.

(Photo: popularresistance.org)

Even Whole Foods, a famed destination for ethical consumers, was forced to stop selling certain artisanal cheeses last year when those “artisans” were revealed to be prisoners who made a base wage of 60 cents a day.

We won’t even get into what Whole Foods — sometimes called “Whole Paycheck” — was charging consumers for prisoner-made products, which also included organic milk and tilapia.

The problem is making its way into popular culture as well. A season three episode of the Netflix prison dramedy Orange Is the New Black, for example, illustrated a similar scam.

In the episode, a thrilling new job opportunity is marketed to the inmates. Most are beside themselves at the idea of working for $1 an hour — well above the compensation offered for any other job in the prison. A scheme is hatched to trick the women into clamoring for the job in a fake competition.

The episode closes with a scene showing the chosen women as their new job is revealed to them. They walk into a warehouse. The lights click on, and the viewer first sees the shock and disappointment on their faces. Then the camera turns to show rows and rows of sewing machines and a corporate logo overhead.

They’d competed to work in a sweatshop.

Real-life prisoners are starting to organize against this kind of abuse. This April, prisoners in Texas held a coordinated work stoppage with the help of the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee — an arm of the global IWW union.

The striking inmates refused to do work assigned to them by Texas Correctional Industries, an arm of the state Department of Justice that uses inmate labor to make everything from personal care items to toilets. Incarcerated workers there are paid as little as 17 cents an hour, even as phone calls can cost $1 a minute and medical care requires a $100 copay.

Another union-coordinated strike is underway at several Alabama prisons, where inmates labor in deplorable conditions even as they generate profits for private industries. Unions and rights groups are gearing up for a national strike this September to derail this exploitative system.

Those most directly and negatively affected, the prisoners and their families, need and deserve our support. But the rest of us need to finish the work of the Civil War and end forced labor in our country for good.

Lauren Karaffa is a New Economy Maryland fellow at the Institute for Policy Studies. Distributed by OtherWords.org.