The Detroit Rebellion of 1967 and Its Global Significance

Lessons for the 21st century and the continuing need for revolutionary organization

This program was designed to acknowledge, commemorate and celebrate the historic July 1967 African American working class rebellion in Detroit and other cities across the United States during the same time period. It is also the beginning of a year-long dialogue on the political significance of this monumental development and what it portended for the world then and some five decades later in the 21st century.

We know that this anniversary will be a nervous one from the standpoint of the white-dominated ruling class and its surrogates. There will be an attempt to frame the Detroit Rebellion as a series of criminal acts devoid of social significance.

Although we are five decades removed from this outbreak of righteous indignation on the part of the oppressed people, the capitalist rulers can never admit that their systematic institutional racism and exploitation serves as the underpinning for all forms of resistance aimed at national liberation and social justice. From the period of slavery right through the failure of Reconstruction to Jim Crow segregation, lynching, the Great Depression, Cold War, and the contemporary period of benign neglect and state repression, African people have fought back against what Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. described as the “triple evils” of racism, war and poverty.

The deliberate distortion of the actual history of Detroit and its African American community is crafted to maintain the social status-quo. Despite the fact that gains were made from the self-organization and emancipatory movements of the post-World War II awakenings and increasing levels of national consciousness, the ruling capitalist class has sought to reverse all advancements won by the people.

Moreover, there are striking parallels with the situation in 2017 and that of 1967. Racism is still very much in evidence. African Americans and other oppressed people are subjected to economic deprivation such as higher unemployment rates, deeper levels of poverty and desperation along with political suppression. The governmental system in the U.S. has never recognized through the Constitution and its amendments the special oppression of the African people who were brought here as slaves.

It was the profits accrued from the exploitation of slave labor and the land stolen from the indigenous people that built America into the most powerful imperialist state. Fundamentally there has been no transformation of the ownership of the means of production or the relations of production.

Consequently, the ruling billionaire firms, their corporate media enablers and the bureaucratic petty-bourgeois functionaries have a vested interest in ignoring the importance of 1967 and all other symbols of resistance and affirmation by the oppressed. They tell us on a daily basis that we should have faith in the capitalist rulers who will save us from the ills that they themselves have perpetuated for centuries.

Therefore, it is essential that we tell our own story. We must remind them of the ongoing exploitation which has rendered the city of Detroit as the most impoverished major municipality in the U.S.

This situation did not develop spontaneously. It is a by-product of a host of policies which favor the rich and deprive the workers and poor. Objectively, we are still locked into to colonial and neo-colonial oppression where the priorities of the wealthy supersede those of the needy and most worthy.

Just over the last decade at least 100,000 households have been dislocated in the city. Many of these people were forced out of Detroit into the suburbs or other cities. Many have remained in the city living in most cases under worst conditions than just a few years ago.

Our homes and apartments have been stolen by the banks and their agents in government working for the ruling class and not the people. Schools within the communities have been closed. The infrastructure of the city has been neglected in its crumbling state. These factors create human ecological damage which propelled hundreds of thousands into uncertainty, sickness and death.

No matter how many lies we are told by the corporate media and the bourgeois politicians it is quite obvious that the situation is getting more dangerous for the people. We know that what is described as the “revitalization” of Detroit is merely another method of extracting more wealth from the majority of the population through low-wage employment, tax captures, and the runaway spending on “prestige projects” which have no real benefit for the masses of working people and the poor.

We have to continue to be the voice of the voiceless. We must project an image of positivity for the struggle against racism, national oppression and super-exploitation. In actuality there is no other solution than the destruction of the capitalist system and the construction of socialism.

The wealth of the city, the state and the U.S. as a whole rightfully belongs to the people. It is our task to organize and mobilize for its seizure and redistribution to those who do the work and have been aggrieved by the ravages of injustice and expropriation on the part of the rich. There can be no compromise in these critical times. The current administration of President Donald Trump represents not a triumph of the ruling class but an illustration of its weakness and desperation. The ideology of the ruling class in the U.S. today is heavily influenced by the shifting demographics where the so-called minorities will become the majority in another quarter century; while at the same time the concentration of wealth is becoming more narrow every decade; and the repressive apparatus of the state is increasing militarized and rationalized under the false notions of combating “illegal immigration”, “Islamic terrorism”, and “crime in the streets.” Indeed we are fighting for our very lives and those of our children along with future generations.

Nonetheless, the real criminals, the capitalist ruling class of bankers, retailers and industrialists remain free to conduct their business of systematic theft. They pay no taxes while we are forced out of our homes, jobs and schools whose value has been reduced to nothing due to the activities of the financial institutions and their collaborators.

As tensions mount throughout the country and indeed the world, it is incumbent upon us to do all that we can to put an end to these violations of human rights and decency. The lessons of 1967 can be quite instructive to the task we are facing in the modern era.

What Actually Happened in 1967?

There are striking similarities between the ruling class narrative of five decades ago and 2017.

Detroit was a “model city” after 1966 ostensibly poised for revitalization in light of already industrial and geographic restructuring. The city was led by a white liberal Democratic Party Mayor Jerome Cavanaugh who was often spoken of a lesser version of President John F. Kennedy. In fact Detroit was even being considered to host the 1968 Olympics and a promotional film was issued in 1963 promoting the city as an ideal setting for the world event.

A peaceful demonstration by Wayne State University students from the group called Uhuru (freedom) that was founded in 1963, at an official event designed to attract attention to Detroit for consideration as the venue for the 1968 Olympics, resulted in arrests. At least one student, John Watson, who later became editor of the South End in 1968 during its revolutionary phase, was taken out of class by the police and charged with a crime even though he was not at the protest action. These students were later acquitted due to the absurd nature of the charges however it was a reflection of the nervousness that prevailed in this time period.

Later in 1966, a mini-rebellion erupted around Kercheval Street on the city’s eastside. The unrest was contained and the Cavanaugh administration was hailed by the corporate media for taking measures that curtailed a large outbreak. That same summer of 1966, urban rebellions took place in 40 cities throughout the U.S. with the largest being in the Hough section of Cleveland in May and in Chicago during July amid the Freedom Movement and the intervention of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The Civil Rights organization in the wake of the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 shifted its focus to Chicago in an attempt to see if the tactics of nonviolent, civil disobedience and mass demonstrations could win concessions from the ruling class.

The Chicago Rebellion of July 1966 came on the heels of the advent of the Black Power slogan enunciated by Willie Ricks and Stokely Carmichael of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) during the “March Against Fear” through the Delta Mississippi in June of that year. Both SCLC and SNCC were blamed for the urban rebellions of 1966 by the racist city administrations and their capitalist benefactors. It was said that the conditions for African Americans in Chicago were far better than what existed in the South and that the problems of slums, joblessness, lack of political representation and police brutality could not be solved overnight.

By early 1967 the social situation in the U.S. had grown more volatile. The escalation of the War in Vietnam robbed resources from the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson’s so-called “Great Society” programs, two of which being “Model Cities” and the “War on Poverty.” Both SCLC and SNCC by 1967 had come out publicly against the occupation of South Vietnam and bombing of the North under the leadership of Ho Chi Minh. Rebellions began to erupt in various cities with Newark, New Jersey being the most widespread starting on July 12.

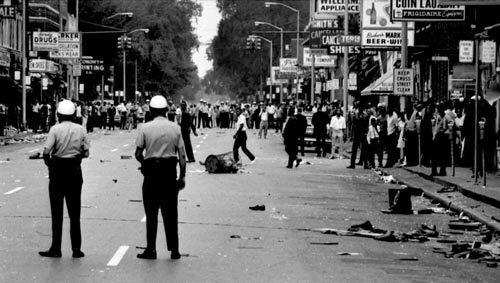

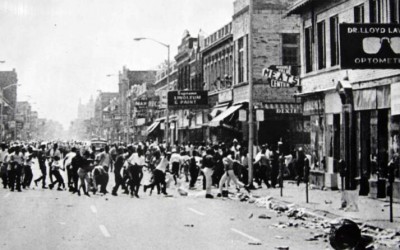

Nevertheless, just 11 days later the city of Detroit seething from decades of de facto segregation and a split racist labor market exploded. Police raided a private club located on 12th Street between Clairmount and Atkinson. The intrusion prompted outrage in the neighborhood as people flooded out into the streets throwing rocks and bottles at the police.

Within a brief period of time windows of the local businesses were smashed while people liberated merchandise. The old Virginia Park 12th Street area was an overcrowded district with deteriorating housing stock and schools, lacking proper resources and public services. African Americans were largely disenfranchised through the citywide municipal governing structure allowing only one Councilperson, Nicholas Hood, in the legislative branch of government.

Police in the initial hours of the rebellion were forced to pull back their forces. It was assumed that the anger would soon subside and people would leave the streets. Congressman John Conyers and Deputy Detroit Public Schools Superintendent Arthur Johnson were sent over to 12th Street in an effort to calm the crowds. The masses were not having any conciliatory talk. They shouted Conyers down. A missile was thrown as a warning for them to leave. Both men soon vanished from the scene.

Hours later in the early afternoon some two dozen businesses were firebombed by youths using Molotov cocktails in rapid succession. The unrest soon expanded to Linwood Avenue just three blocks west of 12th Street. As the news spread through informal channels and the corporate media more people pour onto the streets in the Virginia Park area as well as other parts of the city extending to the east side.

City authorities feeling overwhelmed in the first half-day of the rebellion summoned the-then Governor George Romney of Michigan to deploy the National Guard. These troops began to arrive by the late afternoon and early evening. The people continued to challenge the authorities by liberating merchandise, setting fires to businesses and firing rifles and shotguns at the police and National Guard from buildings.

By late Sunday evening, Gov. Romney was compelled to conduct a flyover of the impacted areas of the city. Large sections of the city were already in flames. Romney then was taken on a guided tour of impacted areas of Detroit concluding that the situation was beyond the capacity of both the local and state police as well as the National Guard to contain. Romney then sent a telegram to President Johnson asking for the deployment of federal troops to assist in restoring order.

Johnson balked at the request from Romney. The Michigan governor had declared recently that he would be seeking the 1968 Republican nomination for the presidency. Romney, a former president and Chairman of the Board of the now-defunct Detroit-based American Motors Corporation (AMC), was a political adversary of LBJ who at that time had a strong possibility of winning re-election the following year. However, the proliferation of urban rebellions and the exposure of the futility of U.S. military policy in Vietnam would result in Johnson’s withdrawal from politics just eight months following the Detroit Rebellion.

The following day as the Rebellion spread throughout larger areas of Detroit, Johnson deployed Special Assistant to the Secretary of Defense Cyrus Vance to the city to survey the situation to determine if the dispatching of federal troops was warranted. By Monday evening July 24, Vance informed Johnson that additional reinforcements were required. Johnson went on national television to explain why troops were being deployed to Detroit. He decried the violence and called for the Rebellion to be halted.

By late Monday evening, thousands of troops from the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions of the U.S. Army were deployed in Detroit. They were to serve as a reserve unit in case the violence escalated to higher levels. By this time National Guard and police were engaging in a reign of terror throughout the city. People were being gunned down at random. Homes and apartments were shot up by Guardsmen saying that were suspected of harboring snipers.

The unrest continued through Thursday July 27. The city was placed under a curfew from 9:00pm to 6:00am. Anyone caught on the street without proper authorization would be arrested. There were several people killed for simply traveling in their vehicles and on foot during the curfew hours.

An article published by Bridge magazine recalled: “The Detroit Fire Department responded to 3,034 calls during the…week. A total of 690 buildings were destroyed or had to be demolished. Two firefighters died and 84 were seriously injured. A fire expert who studied Detroit’s… blazes concluded the ‘city had narrowly averted a firestorm’ like those in Tokyo, Berlin other urban war zones during World War II. Dozens of suburban departments came to Detroit’s aid….It took about 17,000 members of various organizations to quell the [rebellion]: Vietnam-hardened – and integrated – U.S. Army troops from the 82d and 101st Airborne units; Detroit Police; Michigan National Guard; and Michigan State Police. ” (March 11, 2016)

Initial property damage estimates in the Detroit Rebellion extended up to $1 billion. It was later lowered largely for political reasons. By the time the unrest had subsided some 43 people had been killed, the majority of whom were African Americans. Hundreds of others were wounded and suffered multiple injuries. Over 7,200 people were arrested filling the jails beyond capacity leading to the detention of people on busses and at Belle Isle.

Johnson in the same week announced the establishment of a National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorder chaired by Governor Otto Kerner of Illinois. When the report of the panel was issued in late March of 1968, Johnson refused to accept its findings. The Kerner Commission said what most African Americans already knew: that American society was divided into two, one Black and one White. It cited the biased role of the corporate media for fueling tensions and criticized the lack of quality housing, education and employment available to most African Americans.

The Fire Next Time

A recently-released documentary entitled “I Am Not Your Negro” by Raoul Peck, focuses on the life, times and legacy of legendary African American novelist, essayist, playwright and public intellectual James Baldwin (1924-1987). Baldwin had rose to prominence beginning in the late 1940s when he lived as an expatriate in Paris, fleeing from the horrendous levels of racism then prevalent in the U.S.

By the 1950s, Baldwin became a leading literary figure with a string of novels, articles and books of essays which sold millions. In the early 1960s, as the Civil Rights Movement grew more militant, he joined in anti-segregation efforts throughout the South and the North.

The documentary narrated by Samuel L. Jackson is based on the text of an incomplete book by Baldwin in which he was working on at the time of his death. The book was autobiographical in nature, looking at his own experiences through the lives of three leading African American political figures of the period: Medgar Evers, the field secretary of the NAACP in Mississippi; Malcom X, the former spokesperson for the Nation of Islam founded in Detroit in 1930; and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., who had evolved into a principal enemy of the U.S. ruling class by 1967. All three men were assassinated between 1963 and 1968.

Baldwin’s most well-known book is entitled “The Fire Next Time” published in 1963. The work prefigures the rising militancy within the African American nation. It foresaw the urban rebellions based upon the failure of the U.S. ruling class to effectively address the race problem.

What is important to consider in the history of the Civil Rights Movement of the Post-World War II period is the impact of the Cold War generated by the competition surrounding the systems of capitalism and socialism. The U.S. ruling class was compelled in the struggle with the USSR, China, Cuba, Democratic Korea, Vietnam and the national liberation movements, among others, to institute reforms that were being demanded by the domestic situation. The anti-U.S. propaganda value of the continued apartheid conditions existing among African Americans was immense. There was no way that Washington could justify waging war on the socialist countries and the national liberation movements while Africans were being barred from public institutions in the areas of municipal services, education, housing and employment.

The Fire Next Time observes that: “White Americans have contended themselves with gestures that are now described as ‘tokenism.’ For hard example, white Americans congratulate themselves on the 1954 Supreme Court decision outlawing segregation in the schools; they suppose, in spite of the mountain of evidence that has since accumulated to the contrary, that this was proof of a change of heart—or, as they like to say, progress. Perhaps. It all depends on how one reads the word ‘progress’. Most of the Negroes I know do not believe that this immense concession would ever have been made if it had not been for the competition of the Cold War, and the fact that Africa was clearly liberating herself and therefore had, for political reasons, to be wooed by the descendants of her former masters. Had it been a matter of love or justice, the 1954 decision would surely have occurred sooner; were it not for the realities of power in this difficult era, it might very well not have occurred yet.” (pp. 86-87)

As it relates to the social conditions of the African American people there was never any intention by the ruling class to make fundamental changes to the system of national oppression and class exploitation. The appearance of change, or even quantitative improvements, does not equal transformation. If there are no basic alterations of the structural barriers to the achievement of full equality and self-determination, then the question of liberation remains unanswered.

In the Fire Next Time, Baldwin notes: “I think this is a fact, which serves no purpose to deny, but, whether it is a fact or not, this is what the black population of the world, including black Americans, really believe. The word ‘independence’ in Africa and the word ‘integration’ here are almost equally meaningless; that is, Europe has not yet left Africa, and black men here are not yet free. And both of these last statements are undeniable facts, related facts, containing the gravest implications for us all. The Negroes of this country may never be able to rise to power, but they are very well placed indeed to precipitate chaos and ring down the curtain on the American dream.” (pp. 87-88)

1967: High Tide of Black Resistance

Nevertheless, other voices within the African American liberation struggle in subsequent years did articulate a view of not only creating disorder but also working towards the seizure of state power leading to the eradication of the capitalist system. This view was developed in Detroit in the aftermath of the 1967 Rebellion when organizations were founded to bring about what they saw a total freedom.

The findings of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorder could not be accepted by Johnson or the following administration of President Richard M. Nixon. Sentiment in favor of even minimal reforms had shifted to an emphasis on the liquidation of the African American liberation movement through the social containment of the oppressed nation. U.S. imperialism’s priorities in Southeast Asia and Southern Africa, the most evident during the late 1960s and 1970s, influenced the domestic policies in an economic crisis which took hold in the years of 1971-75.

Soon enough an unprecedented level of capitalist restructuring became entrenched within the system itself. This process continues well into the 21st century.

During 1968, an organization was formed in Detroit which distinguished the movement here from anywhere else in the U.S. In February of 1968, a wildcat strike at the Dodge Main Chrysler facility in Hamtramck soon resulted in the formation of the Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM). This organizing model spread to other production facilities in the Detroit area threatening the viability of industrial capitalism at the point of production. These factories employed young African American workers in significant numbers in critical areas of production. Revolutionaries saw this as providing the potential for the disruption of capitalist manufacturing, which was at the time the lifeblood of the profit system.

The following year in April 1969, DRUM, FRUM, ELRUM and other independent African American worker organizations came together with student, youth and community counterparts to form the League of Revolutionary Black Workers (LRBW). The objective of the LRBW was national liberation for the African American people and socialist revolution.

James Foreman, who in 1967 was Director of the International Affairs Commission for SNCC, wrote of that year stressing: “The year 1967 marked a historic milestone in the struggle for the liberation of black people in the United States and the year that revolutionaries throughout the world began to understand more fully the impact of the black movement. Our liberation will only come when there is final destruction of this mad octopus-the capitalistic system of the United States with all its life-sucking tentacles of exploitation and racism that choke the people of Africa, Asia, and Latin America.”

This same document continues saying: “To work, to fight, and to die for the liberation of our people in the United States means, therefore, to work for the liberation of all oppressed people around the world. Liberation movements in many parts of the world are now aware that, when they begin to fight colonialism, it becomes imperative that we in this country try to neutralize the possibilities of full-scale United States intervention as occurred in Santa Domingo, as is occurring in Vietnam, and as may occur in Haiti, Venezuela, South Africa or wherever. While such a task may well be beyond our capacity, an aroused, motivated, and rebelling black American population nevertheless helps in our indivisible struggles against racism, colonialism and apartheid.”

After the formation of the LRBW, the National Black Economic Development Conference (NBEDC) was held in Detroit at Wayne State University from April 25-27, 1969. The gathering sponsored by the Inter-Religious Foundation for Community Organizations (IFCO), brought together a broad range of groups concerned about the future of the African American liberation movement. Out of this Conference a document entitled “The Black Manifesto” was presented and adopted by the BEDC on April 26. The Manifesto was drafted by Forman and it was the first modern-day call for reparations that linked the demand to the struggle against capitalism, imperialism and for socialism in the U.S. and the world.

Forman was invited to relocate in Detroit by Mike Hamlin, a leading member of the LRBW and veteran activist in the revolutionary movement of the 1960s. The former SNCC leader, who had worked briefly as Minister of Foreign Affairs in the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in 1968, was placed on the executive board of the LRBW in 1969 and would later co-found the International Black Workers Congress (BWC) established in late 1970.

The Black Manifesto sought reparations from the white Christian churches and Jewish synagogues which Forman said had benefitted from the national oppression of the African American people. He demanded the immediate payment of $500 million to fund a myriad of projects including printing houses, televised educational projects, a university teaching a revolutionary curriculum, the initiation of an African skills bank to solidify alliances and cooperation between African Americans and independent African states, etc.

In the book entitled “The Political Thought of James Forman” which was compiled, edited and published in the city of Detroit by Black Star in 1970, a division of the LRBW funded by the resources acquired through the Black Manifesto project, Forman says in a letter written from Martinique, the home of the late Dr. Frantz Fanon: “I am in Martinique precisely because I believe that the ideological struggle is most important and that Frantz Fanon has much to say to those of us who are colonized in the United States. More than that, if we do not arm ourselves with sound theoretical concepts we will not survive the severe period of repression which is upon us.”

This same letter written by Forman goes on to observe that: “We all know of too many people and leading personalities who have abdicated the struggle inside the United States for various reasons, but one of them comes from not understanding the long term nature of our struggle and a sound theoretical position that our fight is against racism, colonialism, capitalism and imperialism and that world socialism is the only permanent answer to our economic and political exploitation. Personally, while I believe that ultimately the fight is for world socialism, I am not opposed to short term objectives. For instance, the issue of Pan Africanism is going to hit the stage inside the United States. This will be an advancement over many concepts, but it will not be enough if it does not speak to the economic framework of that Pan Africanism. For inside Africa today there are many bourgeois nationalists running African governments and exploiting the people in the name of Pan Africanism. We have the right to at least demand that people regress from Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois who in his later years was pleading for Pan African Socialism. I am for Pan African socialism if it means taking all the wealth of Africa away from the imperialists and using it for the disposition of all oppressed people. Our ideological positions must lead us to the position that it is the poor, the working class among black people who must have power. During the sixties we concentrated too much on the middle class. Most of the gains except the long range political consciousness have resulted in the middle class of the black community entrenching itself further. Our failure to actively work with black workers is a serious indictment of our movement as well as the abdication of our bases in the rural South.”

Our Task in the 21st Century: Completing the Struggle for National Liberation and Socialism

A combination of state repression, objective factors in the economic restructuring of the U.S. and subjective weaknesses within the revolutionary movement, lead to the demise of the mass mobilizations of the African American liberation struggle of the 1960s and 1970s. Scores of Black mayors and other politicians came into office in Detroit and other cities. Although these events represented a degree of political self-determination, the economic basis for the national oppression and economic exploitation of African American remained intact.

In the present period the capitalist system is even more resistant to tokenism and minimal reforms in the areas of institutional access and expansion of opportunities in the educational sector along with the widening of the labor market. Despite the rhetoric of Donald Trump, the reality of modern-day capitalism is that its survival depends upon the ever increasing rates of profit through the domination of international markets and the super-exploitation of the labor force.

The prison industrial complex provides an excellent example related to the character of global capitalism today. Since 1980, the rate of incarceration in the U.S. has risen by at least 500 percent, with a disproportionate number of inmates being African Americans and Latinos, including immigrants. Trump’s policy of increasing criminalization of the oppressed nations within the U.S. is nothing new. This program has been in existence now for decades.

As a revolutionary organization and movement we must continue to recruit and mobilize among the most potentially organized and disciplined social forces in capitalist society, the nationally oppressed and working class youth. These efforts will advance the level of struggle against the capitalist system. Our efforts are both ideological and political. We must effectively deconstruct the philosophical underpinnings of capitalism and imperialism and then win over the workers and oppressed peoples through our examples of selfless sacrifice and revolutionary commitment.

There is no viable alternative for the future other than socialist construction. This is the contribution that our generations must make to the realization of a world devoid of imperialist war, economic exploitation and national oppression.

The above text was delivered at the Annual African American History Month Forum on Feb. 25, 2017 under this year’s theme focusing on the 50th anniversary of the Great Detroit Rebellion of July 1967 and the lessons learned for the 21st century.

Additional speakers included Mond Toussaint Louverture, youth organizer for Workers World Party in Michigan, who discussed the impact of the theoretical contributions of Frantz Fanon on the worldwide African Revolution; Dorothy Aldridge, chairperson of the Detroit Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Committee, reflected on the Detroit People’s Tribunal established after the 1967 Rebellion; and remarks were made by Lori Parks, an organizer for the Detroit Fight for $15 low-wage workers’ movement. The event was chaired by Debbie Johnson of Workers World Party Detroit branch.