The Chilcot Report Is Out, Tony Blair Apologises But Still Justifies His Decision

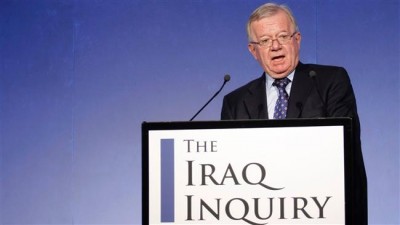

The Chilcot report that enquired into Britain’s decision to join US coalition that attacked Iraq which was released today finds that Britain decided to join the 2003 invasion of Iraq based on “flawed intelligence”. John Chilcot, the chair of the Iraq Inquiry said that the invasion went “badly wrong”.

The 2.6 million-word Iraq Inquiry – which took seven years to prepare – was published in full on Wednesday. It can be accessed online.

Chilcot said:

“The UK chose to join the invasion of Iraq before the peaceful options for disarmament had been exhausted.” Chilcot said that, despite explicit warnings, the consequences of the invasion were underestimated. Investigators also found the planning and preparations for Iraq after Hussein was overthrown were wholly inadequate, said Chilcot, who had not been asked to rule on the legality of the invasion. “The people of Iraq have suffered greatly,” Chilcot said.

Responding to the report, former Prime Minister Tony Blair said in a press conference on Wednesday that he “accept full responsibility without exception and without excuse” for the decision to go to war in Iraq, but insisted that the world “is in a better place without Saddam Hussein”.

He said,

the decision to go to war in Iraq and remove Saddam Hussein from power in a coalition of over 40 countries led by the USA, was the hardest, most momentous, most agonising decision I took in 10 years as British prime minister.

For that decision today I accept full responsibility, without exception and without excuse. I recognise the division felt by many in our country over the war and in particular I feel deeply and sincerely – in a way that no words can properly convey – the grief and suffering of those who lost ones they loved in Iraq, whether the members of our armed forces, the armed forces of other nations, or Iraqis.

The intelligence assessments made at the time of going to war turned out to be wrong. The aftermath turned out to be more hostile, protracted and bloody than ever we imagined. The coalition planned for one set of ground facts and encountered another, and a nation whose people we wanted to set free and secure from the evil of Saddam, became instead victim to sectarian terrorism.

For all of this I express more sorrow, regret and apology than you may ever know or can believe..

Joshua Rozenberg writing for The Guardian opined:

Sir John Chilcot’s inquiry has not, in his words, “expressed a view on whether military action [in Iraq] was legal”. That question, he said, could be resolved only by a court. Still less does his report deal with the question of whether Tony Blair or others should face legal action.

These are highlights of the report

Military action

The UK chose to join the invasion of Iraq before all peaceful options for disarmament had been exhausted. Military action at that time was not a last resort

Military action might have been necessary later, but in March 2003, it said, there was no imminent threat from the then Iraq leader Saddam Hussein, the strategy of containment could have been adapted and continued for some time and the majority of the Security Council supported continuing UN inspections and monitoring

On 28 July 2002, the then Prime Minister Tony Blair assured US President George W Bush he would be with him “whatever”. But in the letter, he pointed out that a US coalition for military action would need: Progress on the Middle East peace process, UN authority and a shift in public opinion in the UK, Europe, and among Arab leaders

Weapons of Mass Destruction

Judgements about the severity of the threat posed by Iraq’s weapons of mass destruction – or WMD – were presented with a certainty that was not justified

Intelligence had “not established beyond doubt” that Saddam Hussein had continued to produce chemical and biological weapons

The Joint Intelligence Committee said Iraq has “continued to produce chemical and biological agents” and there had been “recent production”. It said Iraq had the means to deliver chemical and biological weapons. But it did not say that Iraq had continued to produce weapons

Policy on the Iraq invasion was made on the basis of flawed intelligence assessments. It was not challenged, and should have been

The legal case

The circumstances in which it was decided that there was a legal basis for UK military action were “far from satisfactory”

The invasion began on 20 March 2003 but not until 13 March did then Attorney General Lord Goldsmith advise there was, on balance, a secure legal basis for military action. Apart from No 10’s response to his letter on 14 March, no formal record was made of that decision and the precise grounds on which it was made remain unclear

The UK’s actions undermined the authority of the United Nations Security Council: The UN’s Charter puts responsibility for the maintenance of peace and security in the Security Council. The UK government was claiming to act on behalf of the international community “to uphold the authority of the Security Council”. But it knew it did not have a majority supporting its actions

In Cabinet, there was little questioning of Lord Goldsmith about his advice and no substantive discussion of the legal issues recorded

Iraq’s aftermath

Despite explicit warnings, the consequences of the invasion were underestimated. The planning and preparations for Iraq after Saddam Hussein were “wholly inadequate”

The government failed to achieve the stated objectives it had set itself in Iraq. More than 200 British citizens died as a result of the conflict. Iraqi people suffered greatly. By July 2009, at least 150,000 Iraqis had died, probably many more. More than one million were displaced