The 1983 Nuclear War Scare

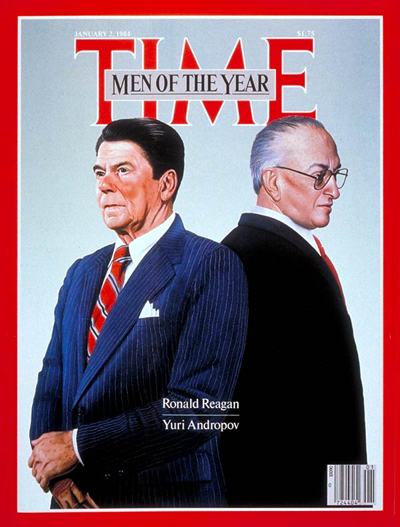

Image: President Reagan and General Secretary Andropov were named “men of the year” in 1983 by the Time Magazine. The Central Intelligence Agency also included an image of this cover in its history of the 1983 War Scare. (Original cover © Time, Inc.)

Soviet “Huffing and Puffing?” “Crying Wolf?” “Rattling Pots and Pans?” or “A Real Worry That We Could Come into Conflict through Miscalculation?”

Largest On-Line Set of Primary Sources on “The Last Paroxysm” of the Cold War Suggests … Both

National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 426

PART 1 OF 3 POSTINGS

Posted – May 16, 2013

Edited by Nate Jones

Assisted by Lauren Harper

With Document Contributions from Svetlana Savranskaya

For more information contact:

Nate Jones 202/994-7000 or [email protected]

Soviet General Secretary Yuri Andropov warned US envoy Averell Harriman that the Reagan administration’s provocations were moving the two superpowers toward “the dangerous ‘red line'” of nuclear war through “miscalculation” in June of 1983. Andropov delivered this warning six months before the 1983 “War Scare” reached its crux during the NATO nuclear release exercise named Able Archer 83, according to Harriman’s notes of the conversation posted for the first time today by the National Security Archive (www.nsarchive.org).

The meeting provides important, first-hand evidence of Soviet leadership concerns about a possible US threat. But other documents included in this posting suggest that not all Soviet political and military leaders were fearful of a US preemptive first strike, but may rather have been “rattling their pots and pans” in an attempt to gain geopolitical advantages, including stopping the deployment of Pershing II and Cruise nuclear missiles in Western Europe. “This would not be the first time that Soviet leaders have used international tensions to mobilize their populations,” wrote the acting CIA director John McMahon in a declassified memo from early 1984.

President Reagan zeroed in on the essence of this debate in March of 1984 when he asked his ambassador to the Soviet Union, Arthur Hartman, “Do you think Soviet leaders really fear us, or is all the huffing and puffing just part of their propaganda?” The evidence presented here, and in two forthcoming electronic briefing books in this series, suggests that the answer to the president’s question was “both.”

This first of three “War Scare” postings also includes KGB reports corroborating the creation of Operation RYaN, the largest peace-time intelligence gathering operation in history, to “prevent the possible sudden outbreak of war by the enemy;” a newly declassified CIA Studies in Intelligence article concluding that Soviet fears of a preemptive U.S. nuclear strike, “while exaggerated, were scarcely insane;” and declassified backchannel discussions between Reagan advisor Jack Matlock and Soviet sources who warned of “growing paranoia among Soviet officials,” whom the source described as “literally obsessed by fear of war.”

The documents in this series provide new information and add nuance to the ongoing debate over the significance — some even argue, the existence — of a genuine war scare in the Soviet Union. The documents come from Freedom of Information Act releases by the CIA and U.S. Defense Department, research findings from American archives, as well as formerly classified Soviet Politburo and KGB files, interviews with ex-Soviet generals, and records from other former communist states.

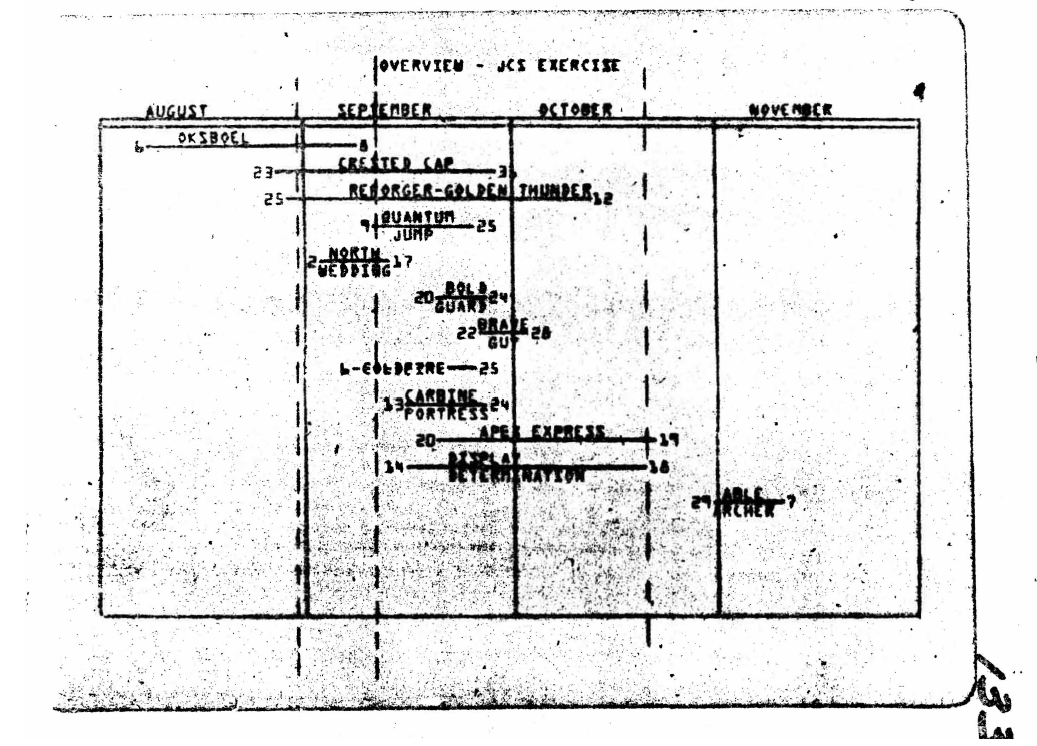

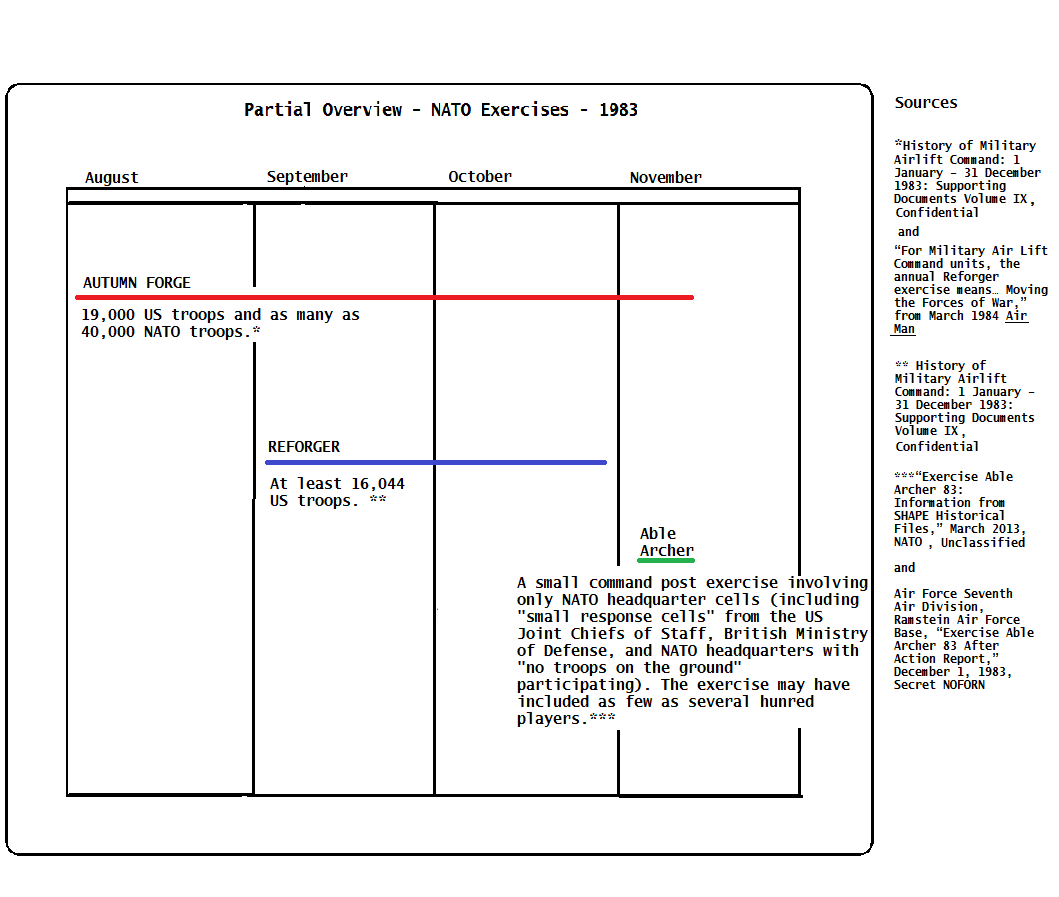

The next electronic briefing book in the series will examine the exercises Autumn Forge 83, Reforger 83, and Able Archer 83, using NATO, U.S. Air Force, and other documents. The third posting will chronicle the U.S. intelligence community’s evolving understanding of and debate over the 1983 War Scare.

* * *

“Do you think Soviet leaders really fear us, or is all the huffing and puffing just part of their propaganda?” President Reagan asked his Ambassador to the Soviet Union, Arthur Hartman in early 1984, according to declassified talking points from the Reagan Presidential Library. President Reagan had pinpointed the question central to the 1983 War Scare. That question was key to the real-time intelligence reporting, the retroactive intelligence estimates and analyses of the danger, and it remains the focus of today’s continuing debate over the danger and lessons of the so-called “Able Archer” War Scare.

Some, such as Robert Gates, who was the CIA’s deputy director for intelligence during the War Scare, have concluded, “After going through the experience at the time, then through the postmortems, and now through the documents, I don’t think the Soviets were crying wolf. They may not have believed a NATO attack was imminent in November 1983, but they did seem to believe that the situation was very dangerous.”[1] Others, such as the CIA’s national intelligence officer for the Soviet Union, Fritz Ermarth, wrote in the CIA’s first analysis of the War Scare, and still believes today, that because the CIA had “many [Soviet] military cook books” it could “judge confidently the difference between when they might be brewing up for a real military confrontation or … just rattling their pots and pans.”[2]

“Huffing and puffing?” “Crying wolf?” “Just rattling their pots and pans?” While real-time analysts, retroactive re-inspectors, and the historical community may be at odds as to how dangerous the War Scare was, all agree that the dearth of available evidence has made conclusions harder to deduce. Some historians have even characterized the study of the War Scare as “an echo chamber of inadequate research and misguided analysis” and “circle reference dependency,” with an overreliance upon “the same scanty evidence.”[3]

To mark the 30th anniversary of the War Scare, the National Security Archive is posting, over three installments, the most complete online collection of declassified U.S. documents, material no longer accessible from the Russian archives, and contemporary interviews, which suggest that the answer to President Reagan’s question — were the Soviets “huffing and puffing” or genuinely afraid? — was both, not either or.

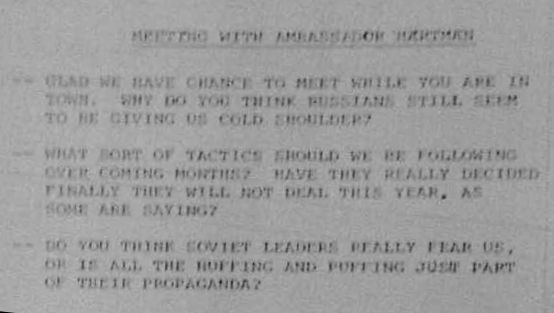

One of Ronald Reagan’s two index cards containing questions for his March 28, 1984 meeting with Ambassador Hartman.

Today’s posting includes:

- U.S. notes of the “first real meeting between the United States and the Soviet Union since the start of the [Reagan] Administration” in June of 1983 between General Secretary Yuri Andropov and U.S. envoy Averell Harriman, in which Andropov warned of nuclear war through miscalculation four times. Harriman, who had negotiated with Stalin during the Second World War, concluded that Andropov, “seemed to have a real worry that we could come into conflict through miscalculation.”

- KGB annual reports for the years 1981 and 1982 corroborating the creation of Operation RYaN (RYaN was the Russian acronym for Raketno-Yadernoye Napadenie, “nuclear missile attack”), the largest peace-time intelligence gathering operation in history to “prevent the possible sudden outbreak of war by the enemy.”

- A CIA memo providing evidence of the “Warsaw Pact Early Warning Indicator Project” – the U.S. intelligence community’s analogue to Operation RYaN.

- An unpublished, declassified CIA Studies in Intelligence article (different from the well-circulated CIA unclassified monograph) which provides a narrative of the War Scare and concludes that Soviet fears of a preemptive U.S. nuclear strike, “while exaggerated, were scarcely insane,” and disclosing that the United States also had an intelligence source in Czechoslovakia partially corroborating the British intelligence asset Oleg Gordievsky’s reporting that Soviet leaders feared an imminent war.

- Volume four of the National Security Agency’s previously classified history, American Cryptology during the Cold War, 1945-1989 (Volumes one through three can be foundhere), which chronicles the years 1980-1989, and asserts that “the period 1982-1984 marked the most dangerous Soviet-American confrontation since the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

- Declassified backchannel discussions between Reagan advisor Jack Matlock and Soviet sources who warned of “growing paranoia among Soviet officials” whom the source described as “literally obsessed by fear of war.”

- Interviews with high level “unhappy Cold Warriors” in the Soviet military, conducted in the early 1990s, in which they explain their recollections and experiences during the War Scare.

Before reviewing the documents, it is important to note that the NATO exercise was not known to Soviet intelligence as “Able Archer 83” at the time it was being conducted. Soviet analysts referred to it as “Autumn Forge 83,” the name for the larger, months-long, series of NATO maneuvers, of which Able Archer was the conclusion.[4] Most American military and intelligence analysts would have known the exercise as “Reforger 83,” which occurred during the final phase of Autumn Forge with a momentous “show of resolve” by air-lifting 19,000 troops and 1,500 tons of cargo from the United States to Europe to simulate a conventional war. Able Archer 83, sponsored by the NATO Supreme Allied Commander in Europe (SACEUR) and conducted from 7 to 11 November 1983, simulated the transition from conventional to nuclear war.

The name “Able Archer 83” came into vogue with the first public exposé of the incident in an October 16, 1988, Sunday Telegraph article entitled “Brink of World War III: When the World Almost Went to War.” Hence, “Able Archer 83,” the term most used by the historical community, was not the term most commonly used by actors as the event transpired. In one interview (to be published in a forthcoming Electronic Briefing Book (EBB) in this series), the head of the Soviet General Staff, Marshal Sergei Akhromeyev, states that he did “not remember” Able Archer 83 but added that “[w]e believed that the most dangerous military exercises were Autumn Forge and Reforger.” This suggests that some Soviet “non-recollections” of “Able Archer” may not be the best evidence for a lack of danger, and that the War Scare deserves further declassification, research, and examination.[5]

Below, for submission into the “echo chamber,” is the first of three Electronic Briefing Books on the War Scare. This first posting will examine: the unprecedented Soviet espionage effort, Operation RYaN; the “fear of war [that] seemed to affect the elite as well as the man on the street” and that led to the operation; and the Reagan administration’s internal debates over the veracity of Soviet attitudes — whether they were “huffing and puffing” or genuinely fearful. The second EBB will examine the exercises Autumn Forge 83, Reforger 83, and Able Archer 83, using NATO, U.S. Air Force, and other documents. The third posting will chronicle the U.S. intelligence community’s evolving understanding of and debate over the 1983 War Scare.

THE DOCUMENTS

Listed non-chronologically to present a clearer narrative.

Document 1: Talking Points for Meeting with Ambassador to the Soviet Union Arthur Hartman, March 28, 1984, Confidential.

Source: Reagan Presidential Library, Matlock files, Chron June 1984, Box 5.

Reagan held two index cards with three questions printed on them during his meeting with Ambassador Hartman in the Oval Office. The final one, “Do you think Soviet leaders really fear us, or is all the huffing and puffing just part of their propaganda?” remains the most important question of the 1983 War Scare. In his diary, Reagan wrote, “Art Hartman came by. He’s truly a fine Ambas. It was good to have a chance to pick his brains.” [6] But, emblematic of the state of the ongoing War Scare debate, no record of Hartman’s response to Reagan’s question has been found.

The Wikipedia article on Able Archer 83 the National Security Agency sent us in response to a FOIA request.

Document 2: American Cryptology During the Cold War, 1945 – 1989, Book IV: Cryptologic Rebirth, 1981-1989, Thomas R. Johnson, National Security Agency Center for Cryptologic History, 1999, Top Secret-COMINT-UMBRA/TALENT KEYHOLE/X1.

Source: National Security Agency Freedom of Information Act release.

Volume four of the National Security Agency’s heavily redacted study on cryptology during the Cold War (see here for earlier volumes), released to the National Security Archive through the FOIA, is devoted to the Reagan era. The NSA starkly notes that “[t]he Reagan administration marked the height of the Cold War. The president referred to the Soviet Union as the Evil Empire, and was determined to spend it into the ground. The Politburo reciprocated, and the rhetoric on both sides, especially during the first Reagan administration, drove the hysteria. Some called it the Second Cold War. The period 1982-1984 marked the most dangerous Soviet-American confrontation since the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

The National Security Agency responded to a 2008 FOIA request on the War Scare by stating that it had 81 relevant documents, but that all were exempt from release. Unhelpfully, the Agency did review, approve for release, stamp, and send a printout of a Wikipedia article.

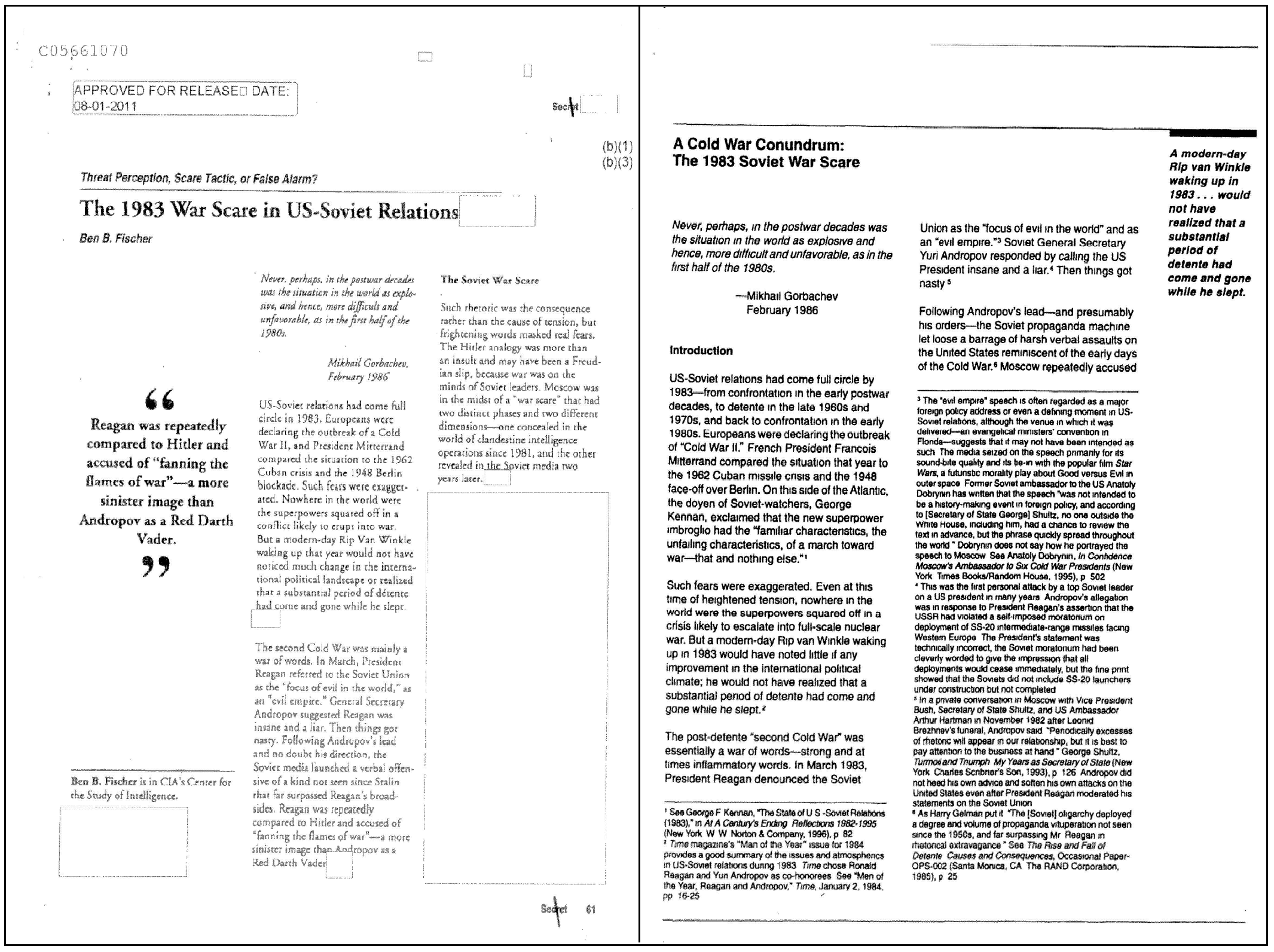

Document 3: CIA Studies in Intelligence article by Benjamin B. Fischer, “The 1983 War Scare in US-Soviet Relations,” Undated, circa 1996, Secret.

Source: Central Intelligence Agency Freedom of Information Act release.

Two CIA histories -one declassified and redacted, the other unclassified- chronicle the geopolitical factors that made the War Scare “the most dangerous Soviet-American confrontation since the Cuban Missile Crisis.”

“The 1983 War Scare in US-Soviet Relations,” by Ben B. Fischer, a History Fellow at the CIA’s Center for the Study of Intelligence, was authored for the CIA’s classified in-house journal, Studies in Intelligence — likely prior to the presentation of his longer, unclassified, “A Cold War Conundrum,” although its date is redacted. “The 1983 War Scare in US-Soviet Relations” concludes that Soviet fears of a preemptive U.S. nuclear strike, “while exaggerated, were scarcely insane.” Fischer’s account starkly claims that the U.S. dismissal of legitimate Soviet fears, including of a “decapitating” nuclear strike, left the U.S. vulnerable to the possibility that they could lead to very real dangers, including a preemptive Soviet nuclear strike based purely on misinformation.

After President Reagan’s March 1983 assertion that the USSR had violated a self-imposed moratorium on deploying intermediate-range SS-20 missiles facing Western Europe, General Secretary Andropov suggested that Reagan was “insane and a liar,” repeatedly compared him to Hitler, and espoused rhetoric that made it seem war was imminent. Fischer writes that U.S. officials gave little credence to Soviet concerns — or dismissed them as propaganda — and argues that the fears were more nuanced than mere political pandering, as evidenced by Operation RYaN.

According to Fischer’s account, based largely on the MI6 and CIA asset Oleg Gordievsky, in 1981 the Soviet Union launched Operation RYaN, a combined intelligence effort among the KGB and their GRU (military intelligence) counterparts, to monitor indications and warnings of U.S. war-planning, and by 1983 RYaN had acquired “an especial degree of urgency.” RYaN was, according to Fischer, “for real,” and was in part a likely byproduct of American PSYOP tactics conducted throughout the previous two years.

The report also extablishes — for the first time — that another CIA source was, at least partially, corroborating Gordievsky’s reporting. This Czechoslovak intelligence officer — who worked closely with the KGB on RYaN — “noted that his counterparts were obsessed with the historical parallel between 1941 and 1983. He believed this feeling was almost visceral, not intellectual, and deeply affected Soviet thinking.”

This CIA history also reveals that the U.S. military had been probing Soviet airspace to pinpoint vulnerabilities since the beginning of the Reagan administration, and that in 1981 the U.S. Navy led an armada of 83 ships through Soviet waters, effectively eluding “the USSR’s massive ocean reconnaissance system and early-warning systems.” In addition to the PSYOP exercises, and in the heated aftermath of the KAL 007 tragedy of September 1, 1983, the U.S. Navy flew aircraft 20 miles inside Soviet airspace, prompting Andropov to issue orders that “any aircraft discovered in Soviet airspace be shot down. Air-defense commanders were warned that if they refused to execute Andropov’s order, they would be dismissed.” Tensions, and Moscow’s suspicions of a possible U.S. attack, were high. These events rattled Soviet leaders, already aware that their technological capabilities were lagging behind the U.S., and they ramped up Operation RYaN efforts.

Fischer writes that as the Soviets were conducting Operation RYaN, the U.S. began Able Archer 83, an annual NATO command post exercise that the Soviets were familiar with. However, Gordievsky told MI6 that during Able Archer 83, Moscow incorrectly informed its KGB and GRU stations that U.S. forces were mobilizing in Europe. Air bases in East Germany and Poland were put on alert “for the first and last time during the Cold War.” Fischer points out that while the White House was cognizant of Soviet anxiety in the aftermath of Able Archer 83 by way of Gordievsky, there is no corroborating evidence of fear of imminent war from the Kremlin itself, and that other senior Soviet leaders later reported “that none had heard of Able Archer.” (Importantly, there was no mention of Autumn Forge or Reforger.) Though Gordievsky’s accounts were uncorroborated, they undoubtedly influenced U.S. attitudes toward the Soviets.

Fischer concludes that Operation RYaN and the urgency to collect intelligence on U.S. capabilities was more than what Reagan called “huffing and puffing.” He adds that the fear was magnified by the growing technological disparity between the two superpowers, and describes Able Archer 83 as the “last paroxysm at the end of the Cold War.”

Document 4: Central Intelligence Agency Intelligence Monograph by Benjamin B. Fischer, “A Cold War Conundrum: The 1983 Soviet War Scare,” September 1997, Unclassified.

Source: CIA Electronic Reading Room.

A second, well-circulated historical monograph published by Ben B. Fischer, “A Cold War Conundrum: The 1983 Soviet War Scare” in the CIA’s An Intelligence Monograph series, is a longer, unclassified update of his classified piece, “The 1983 War Scare in US-Soviet Relations” (see previous document). With a careful reading, “A Cold War Conundrum” gives insight into what the CIA censored from his earlier, redacted Studies in Intelligence piece. While much of the information is the same, the CIA likely redacted passages about the Soviet’s recognition of their own capabilities, their feelings of vulnerability surrounding recent international disappointments, Oleg Gordievsky’s credibility, and the competence of MI6.

This unclassified article also describes a 1981 KGB estimate of world trends, redacted from the earlier piece, that concludes that the “USSR in effect was losing — and the US was winning — the Cold War.” While Fischer’s redacted article refers to the Soviets’ acknowledgment of an unfavorable “correlation of world forces,” this unclassified article underscores the USSR’s feelings of vulnerability as it was caught in “its own version of America’s Vietnam quagmire” in Afghanistan, was being drained economically by Cuba, and was struggling to support the pro-Soviet regimes in Angola and Nicaragua. These vulnerabilities were likely amplified by a visible shift in U.S. public opinion, which now supported the “largest peacetime defense buildup in the nation’s history.”

The unclassified article also hints at what the largest bulk of redacted portion material likely discusses Oleg Gordievsky. In Appendix B, the unclassified paper outlines the circumstances surrounding Gordievsky’s relationship with MI6 as well as potential bona fides and blemishes on his credibility and track record. While Fischer generally considers Gordievsky credible and bona fide, the CIA’s declassifiers have redacted information that supports his credibility, including the fact that the British debriefed him “150 times over a period of several months, taking 6,000 pages of notes that were reviewed by analysts. Everything checked out, and no significant inaccuracies or inconsistencies were uncovered.”

The description of CIA rival MI6 as “a storehouse of priceless information which even the CIA would find useful” was also omitted in the earlier article.

Document 5: Department of State memo from Frank H. Perez, Office of Strategic and General Research at the Bureau of Intelligence and Research, to Leonard Weiss, Deputy Director for Functional Research at the Bureau of Intelligence and Research, “Subject: Thoughts on Launch–on–warning,” January 29, 1971, Secret.

Source: National Archives, RG 59, Subject-Numeric Files, 1970-1973, Def 12 USSR January 29, 1971, Secret, and related documents .

Document 6: Secretary of Defense to President Carter, “ False Alerts ,” July 12, 1980, Top Secret, excised copy, and related documents .

Source: Source: Defense Department Freedom of Information Act release.

The primary impetus for Operation RYaN was the Soviet fear of a preemptive nuclear strike driven by both superpowers’ reliance on Launch-on-Warning nuclear postures, combined with the planned deployment of Pershing II missiles that could reach Moscow from West Germany in six minutes.[7] This led to Soviet worries of a “decapitating first strike” and the initiation of Operation RYaN to detect, and possibly preempt this first strike before its launch.

U.S. national security advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski was the victim of one terrifying example proving the danger posed by shrinking warning times, which he recounted to his aide, Robert Gates. Gates, who later served as director of Central Intelligence and secretary of defense, recounted in his memoirs that on November 9, 1979, Brzezinski “was awakened at three in the morning by [military assistant William] Odom, who told him that some 250 Soviet missiles had been launched against the United States. Brzezinski knew that the President’s decision time to order retaliation was from three to seven minutes …. Thus he told Odom he would stand by for a further call to confirm Soviet launch and the intended targets before calling the President. Brzezinski was convinced we had to hit back and told Odom to confirm that the Strategic Air Command was launching its planes. When Odom called back, he reported that … 2,200 missiles had been launched — it was an all — out attack. One minute before Brzezinski intended to call the President, Odom called a third time to say that other warning systems were not reporting Soviet launches. Sitting alone in the middle of the night, Brzezinski had not awakened his wife, reckoning that everyone would be dead in half an hour. It had been a false alarm. Someone had mistakenly put military exercise tapes into the computer system.” [8] In 1980 alone, U.S. warning systems generated three more false alerts.

Valentin Falin, a high ranking Soviet official in the Foreign Ministry, described Soviet anxieties in the Central Committee’s prominent journal, Kommunist. He wrote that with the deployment of Pershing II missiles in 1983, “[i]mperialism has decided to limit both the time and the space of the USSR and for all the world of socialism, to just five minutes for contemplation in a crisis situation.”[9]

President Reagan also realized this danger, writing in his memoirs, “We had many contingency plans for responding to a nuclear attack. But everything would happen so fast that I wondered how much planning or reason could be applied in such a crisis … Six minutes to decide how to respond to a blip on a radar scope and decide whether to unleash Armageddon! How could anyone apply reason at a time like that?”[10]

Document 7: Interview with Viktor M. Surikov, Deputy Director of the Central Scientific Research Institute, by John G. Hines, September 11, 1993 in Soviet Intentions 1965-1985: Volume II Soviet Post-Cold War Testimonial Evidence, by John G. Hines, Ellis M. Mishulovich, of BDM Federal, INC. for the Office of the Secretary of Defense Net Assessment. Unclassified with portions “retroactively” classified.

Source: Defense Department Freedom of Information Act release.

In 1995, the Pentagon contractor, BDM Corporation, prepared a two-volume study on Soviet Intentions, 1965-1985, based on an extraordinarily revealing series of interviews with former senior Soviet defense officials — “unhappy Cold Warriors” — during the final days of the Soviet Union. The interviews contain candid Soviet reflections on the 1983 War Scare.

One interviewee, Viktor Surikov, who had over 30 years experience building, testing, and analyzing military missiles and related systems, acknowledged that a shift toward preemption had occurred on the Soviet side as well. Surikov challenged his interviewer, John Hines, alleging that “U.S. strategy and posture was to strike first in a crisis in order to minimize damage to the U.S. He added that U.S. analysts had concluded that there were tremendous differences in levels of damage to the U.S. under conditions where the U.S. succeeded in successfully preemptively striking Soviet missiles and control systems before they launched versus under conditions of a simultaneous exchange or U.S. retaliation. He said, ‘John, if you deny that, then either you’re ignorant about your own posture or you’re lying to me.’ I acknowledged that the U.S. certainly had done such analysis.”

Surikov believed that the basic Soviet nuclear position and posture was also preemption. Soviet General Valentin Varennikov, who served on the General Staff, corroborates this dangerous change in nuclear warfighting. He recounts that in 1983, the Soviet military conducted its own exercise,Zapad (West) 83, which, “prepared (for the first time since the Second World War) for a situation where our armed forces obtained reliable data of [an adversary’s] decision made by highest military and political leadership to launch a surprise attack, using all possible firepower (artillery, aviation, etc.) against us. In response, we conducted offensive operations to disrupt the enemy attack and defeat its troops. That is, a preemptive strike.”[11]

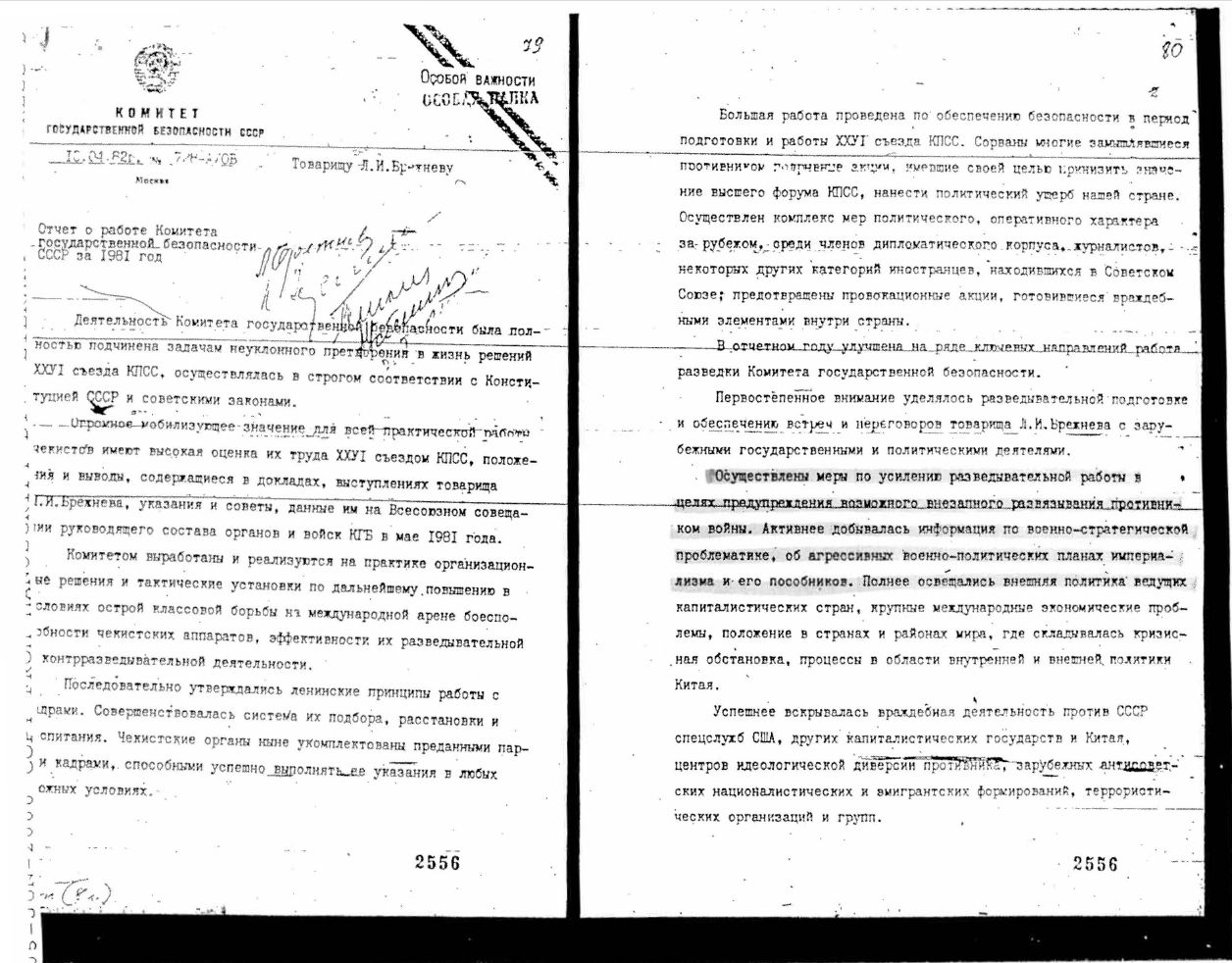

Document 8: KGB Chairman Yuri Andropov to General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev, “Report of the Work of the KGB in 1981,” May 10, 1982, and General Secretary Yuri Andropov from Victor Chebrikov, “Report of the Work of the KGB in 1982,” March 15, 1983.

Source: Dmitrii Antonovich Volkogonov Papers. Available at the National Security Archive.

While Yuri Andropov’s 1981 KGB report to Leonid Brezhnev did not use the specific term “Operation RYaN,” it did state that the KGB had “implemented measures to strengthen intelligence work in order to prevent a possible sudden outbreak of war by the enemy.” To do this, the KGB “actively obtained information on military and strategic issues, and the aggressive military and political plans of imperialism [the United States] and its accomplices,” and “enhanced the relevance and effectiveness of its active intelligence abilities.”

The 1982 report — this time sent to General Secretary Andropov from KGB Chairman Victor Chebrikov — confirmed genuine Soviet fears of encirclement. It noted the challenges of counting on “U.S. and NATO aspirations to change the existing military-strategic balance,” and, as such, “Primary attention was paid to military and strategic issues related to the danger of the enemy’s thermonuclear attack.”

These KGB reports (although they do not mention collaboration with the GRU — Soviet military intelligence) square with Gordievsky’s account of the establishment of RYaN.

Gordievsky wrote in 1991, that “In May of 1981 the ageing Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev denounced Reagan’s policies in a secret address to a major KGB conference in Moscow. The most dramatic speech, however, was given by Yuri Andropov, [then] Chairman of the KGB … The new American administration, he declared, was actively preparing for nuclear war. To the astonishment of his audience, Andropov then announced that, by a decision of the Politburo, the KGB and GRU were for the first time to cooperate in a worldwide intelligence operation codenamed RYaN.” [12]

Document 9: KGB Headquarters Moscow, to the London KGB Residency, “Permanent operational assignment to uncover NATO preparations for a nuclear missile attack on the USSR,” and enclosed documents, February 17, 1983, Top Secret.

Source: Christopher Andrew and Oleg Gordievsky, Comrade Kryuchkov’s Instructions: Top Secret Files on KGB Foreign Operations, 1975-1985, (Stanford: Stanford University Press 1991).

According to Gordievsky, each station chief in “Western countries, Japan, and some states in the Third World” received an Operation RYaN directive. Each was addressed by name, labeled “strictly personal,” and was designated to be kept in a special file. The directive stated:

“The objective of the assignment is to see that the Residency works systematically to uncover any plans in preparation by the main adversary [USA] for RYaN and to organize a continual watch to be kept for indications of a decision being taken to use nuclear weapons against the USSR or immediate preparations being made for a nuclear missile attack.” [13]

Attached to the telegram was a list of seven “immediate” and thirteen “prospective” tasks for the agents to complete and report. These included: the collection of data on potential places of evacuation and shelter, an appraisal of the level of blood held in blood banks, observation of places where nuclear decisions were made and where nuclear weapons were stored, observation of key nuclear decision makers, observation of lines of communication, reconnaissance of the heads of churches and banks, and surveillance of security services and military installations.

Many of the assigned observations would have been very poor indicators of a nuclear attack. Others, including communications lines, nuclear decision makers, and – most significantly – missile depots, might have accurately shown whether a nuclear attack was imminent.

Also attached to the telegram was a thorough and accurate description of the likely methods by which the United States or NATO would launch nuclear war, including a summary of the five DEFCON levels, here called “operational readiness” levels. This attachment emphasized that once the West had decided to launch a nuclear attack; a substantial preparatory period would be required. These preparations included nuclear consultations through secret channels, transportation of nuclear weapons, and preparation of civil defense institutions.

Regrettably, Comrade Kryuchkov’s Instructions include a facsimile reproduction of only the first page of this document. The additional pages were translated and typeset into English with no Russian corroboration of their authenticity.

Document 10: “MVR Information re: Results from the work on the improvement of the System for detection of RYAN indications, 9 March 1984,” and related documents, Top Secret.

Source: Archive of the Ministry of the Interior and Diplomatic Archive of Bulgaria. Kindly provided by Prof. Jordan Baev.

Documents from other Warsaw Pact countries corroborate Soviet descriptions of Operation RYaN. A Top Secret 1984 Bulgarian intelligence document provided instructions to its agents to monitor underground networks, diplomatic representatives from NATO, combat readiness in neighboring countries, and radio-electronic intelligence. Sources from Czech intelligence also confirm the existence of Operation RYaN and show that compiling an “index of sudden aggression” was the primary mission of Warsaw Pact intelligence agencies.[14] Fischer’s history reports that the German Democratic Republic’s Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung, (Main Reconnaissance Administration) played a large role in Operation RYaN. Marcus Wolf, known as “the man without a face,” who served for decades as East Germany’s spymaster wrote, “our Soviet partners had become obsessed with the danger of a nuclear missile attack.” [15]

One document shows that the Bulgarians monitored “VRYAN indicators” as late as June 1987, and East German documents show that the operation continued until 1990.[16]

Document 11: National Intelligence Officer for Warning to Director of Soviet Analysis [CIA] from, “Subject: Warsaw Pact Early Warning Indicator Project,” 1 February 1985, Secret.

Source: Central Intelligence Agency Freedom of Information Act release.

As this heavily redacted memo shows, Operation RYaN had its analogue in U.S. intelligence gathering. The CIA was also working with the DIA, and presumably allied intelligence agencies, to create a list of indicators — including the defense industry — for its chiefs of station to monitor, in an attempt to “emphasize greater early warning cooperation with intelligence services.”

Other parallels to RYaN date back to 1961, when the Soviets also instructed embassies in all “capitalist” countries to collect and report information during the Berlin Crisis. In 1991, one might have deduced the January 16 Desert Storm invasion by monitoring the influx of pizza deliveries to the Pentagon, according to current U.S. Army Operational Security (OPSEC) training materials.

Document 12: Notes of a Conversation with Secretary of State George Shultz, Undersecretary of State Lawrence Eagleburger, and Averell Harriman, Undated (prior to Harriman’s trip to the Soviet Union). (Circa May 1983).

Source: W. Averell Harriman Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Box 655.

In May of 1983 — as the Soviets were conducting Operation RYaN — Averell Harriman, who had served as the U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union during the Second World War, would meet face to face with General Secretary Andropov to “size up” the disposition of the Soviet leadership and attempt to determine their perspectives and intentions.

Before travelling to the Soviet Union, Harriman met with Secretary of State George Shultz. The two discussed how Harriman should approach his meeting, agreeing that Harriman should state he is meeting as a private citizen. They also decided that they should continue to push for expanded contact with the Soviet Ambassador to the United States, Anatoly Dobrynin. Shultz told Harriman that since he had “talked with the Soviets more than anyone else” he should “size up” the way that Andropov behaves and estimate “his desire for a better relationship with the US.” Harriman concluded the conversation by alluding to the President’s confrontational rhetoric, telling Shultz, “I do wish the President could be more careful.”

Shultz himself had met Andropov only briefly in November 1982 at Brezhnev’s funeral. Shultznoted at the time that he got the feeling the new GenSec “could take us on” and that he “still had a great deal of energy about him” after shaking some 2,000 hands.

Document 13: Memorandum of Conversation with Institute for USA and Canada Studies Director Georgy Arbatov and Averell Harriman, May 31, 1983.

Source: W. Averell Harriman Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Box 655.

Two days before the meeting with Andropov, the well-connected expert Georgy Arbatov talked to Harriman to “preview” the meeting with the General Secretary. Arbatov revealed Soviet anxiety over the strained state of U.S.-USSR relations, telling Harriman that, “In the Soviet view, this was the first real meeting between the United States and the Soviet Union since the start of the current [Reagan] Administration.”

A photo of Soviet leader Yuri Andropov from the NSA’s American Cryptology During the Cold War, 1945 – 1989, Book IV: Cryptologic Rebirth, 1981-1989.

Document 14: Memorandum of Conversation between General Secretary Yuri Andropov and Averell Harriman, 3:00 PM, June 2 1983, CPSU Central Committee Headquarters, Moscow.

Source: W. Averell Harriman Papers, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Box 655.

Harriman met with General Secretary Andropov for an hour and twenty minutes. Harriman told Andropov he was travelling as a private citizen but was accompanied with a translator provided by the Department of State. Harriman’s notes show that he believed that Andropov’s fear of war through miscalculation was genuine, rather than — to quote Reagan — “huffing and puffing.”

Andropov opened the conversation by stating: “Let me say that there are indeed grounds for alarm.” He bemoaned the harsh anti-Soviet tone of President Reagan and warned that, “The previous experience of relations between the Soviet Union and the United States cautions beyond all doubt that such a policy can merely lead to aggravation, complexity and danger.” Andropov alluded to nuclear war four times during his short statement; most ominously, he morosely stated, “It would seem that awareness of this danger should be precisely the common denominator with which statesmen of both countries would exercise restraint and seek mutual understanding to strengthen confidence, to avoid the irreparable. However, I must say that I do not see it on the part of the current administration and they may be moving toward the dangerous ‘red line.'”

Harriman concluded: “the principal point which the General Secretary appeared to be trying to get … was a genuine concern over the state of U.S.-Soviet relations and his desire to see them at least ‘normalized,’ if not improved. He seemed to have a real worry that we could come into conflict through miscalculation.”

Document 15: “Meeting of the Politburo,” Working notes, August 4, 1983, Top Secret.

Source: Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Dmitrii Antonovich Volkogonov Papers, Container 26, Reel 17.

Two months after meeting with Harriman, Andropov presided over an August 1983 Politburo meeting — one of the last he attended before being committed to a hospital bed beginning in September — and spoke of using “diplomatic propaganda actions” to stop the deployment of Pershing II missiles. Andropov enumerated three measures the Soviet leadership needed to take to attempt to stop the November deployment in Western Europe of the Pershings, which could reach Moscow in less than six minutes -striking before the Soviet leadership could retreat to their bunkers.

“1. We must not lose time setting in motion all the levers that could impact the governments and parliaments of the NATO countries in order to create maximum obstruction on the path of deployment of American missiles in Europe.

2. It is essential to smartly and precisely coordinate all of this, so diplomatic propaganda actions must complement and reinforce each other.

3. Steps should not be formal, but specifically designed to produce the effect [of aborted deployment].”

Andropov’s speech confirms that the Soviets were using propaganda as a tool to stop the deployment of Pershing II missiles, but also reflected the Soviet fear of the destabilization of the nuclear balance referenced in the 1981 and 1982 KGB reports.

Document 16: Unpublished Interview with State Department Official Mark Palmer, (Excerpt), Undated, circa 1989-1990.

Source: Princeton University, Mudd Manuscript Library, Don Oberdorfer Papers 1983-1990, Series 3, Research Documents Files.

The late Mark Palmer, a top Kremlinologist in the State Department (and U.S. ambassador to Hungary from 1986 to 1990), retrospectively summarized the Reagan administration’s internal “argument” about “what the Soviet view of the West is,” in an unpublished interview with The Washington Post‘s Don Oberdorfer.

“Paul [Nitze’s and others] view is that they [the Soviets] never really felt threatened …And most Western analysts — or many, particularly the political-military type analysts feel that way, because they have a hard time, I think, psychologically seeing, as most people do, seeing themselves as possibly being a bad guy in anyone else’s eyes….

“I, on the other hand, think that what Gordievsky [whom he met] reported in ’81 and etc. — that he’s reporting accurately the mood in Moscow. That the Soviets have felt surrounded, that they are paranoid, that they have seen us as being unpredictable and irresponsible from their point of view in doing all sorts of things — invading communist countries, etc, all sorts of stuff. Therefore, I find this entirely credible that they could have, during [what was] a very tense period anyway, [] saw the INF deployments as a threat to them. These were missiles that could hit the Soviet Union. Their [analogous] missiles -the SS 20s- could not hit the United States.”

Document 17: United States Information Agency Memorandum for CIA Director William J. Casey, from Charles Z. Wick, “Soviet Propaganda Alert No. 13,” May 5, 1983, Unclassified.

Source: CIA Records Search Tool (CREST) at the National Archives, Doc No/ESDN: CIA RDP85M00364R001903760018-0.

The USIA’s “Soviet Propaganda Alerts” regularly reported to policymakers news summaries from the Soviet press framed as propaganda orchestrated by the Soviet leadership for political means.

The thirteenth issue of the “Soviet Propaganda Alert,” sent to CIA Director William Casey, relayed that Soviet media had reported that the Pentagon was making “horrendous plans for unleashing and conducting protracted nuclear war against the Soviet Union.” Soviet media described the U.S. strategy as “escalating a conflict to nuclear war and delivering a first strike, in particular by intermediate-range missiles in Western Europe.”

Document 18: “Subject: U.S.-Soviet Relations,” The White House Memorandum of Conversation, October 11, 1983, Secret.

Source: Reagan Presidential Library, Matlock Files, Chron October 1983 [10/11/1983-10/24/1983], Box 2, 90888.

U.S.-Soviet backchannel contacts warned that the tense atmosphere in the Soviet Union was not only propaganda. This memo summarizes NSC Soviet expert Jack Matlock’s lunch meeting with Sergei Vishensky, a columnist for Pravda, with “sound Party and (almost certainly) KGB credentials” at The Buck Stops Here Cafeteria. Vishensky, whom Matlock believes was “conveying a series of messages someone in the regime wants us to hear,” warned that “the state of U.S.-Soviet relations has deteriorated to a dangerous point. Many in the Soviet public are asking if war is imminent.” He also told Matlock that “the leadership is convinced that the Reagan Administration is out to bring their system down and will give no quarter; therefore they have no choice but to hunker down and fight back.”

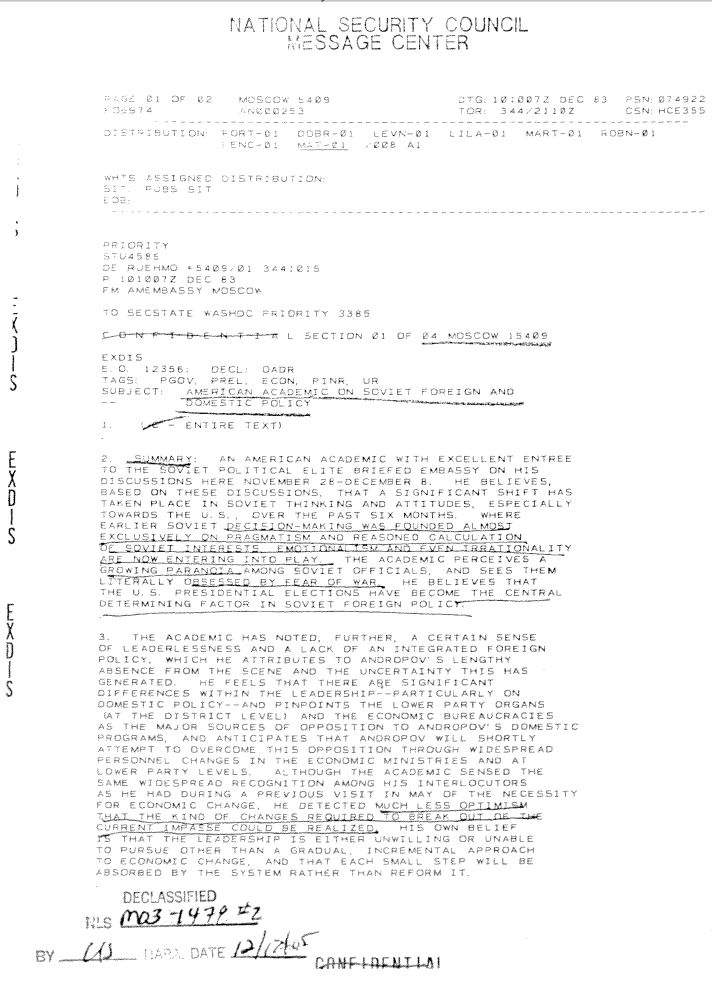

A December 10, 1983, National Security Council memorandum on Soviet foreign and domestic policy states that “emotionalism and even irrationality are coming into play.”

Document 19: Memorandum for National Security Advisor Robert McFarlane from Soviet expert Jack Matlock, “Subject: American Academic on Soviet Policy,” December 13, 1983, Confidential with attached EXDIS cable from the American Embassy in Moscow.

Source: Reagan Presidential Library, Matlock Files, Chron December 1983 [1 of 2], Box 2, 90888

Other sources confirmed this fear of war. In February, Jack Matlock sent National Security Advisor Robert McFarlane a memo warning that since mid-1983, a “fear of war seemed to affect the elite as well as the man on the street.” He attached a copy of a December 10, 1983, cable describing information from “an American academic with excellent entrée to the Soviet political elite.” The academic warned of “growing paranoia among Soviet officials and sees them literally obsessed by fear of war,” and a growing “emotionality and even irrationality” among the elite. The attached EXDIS cable goes further, recounting “a high degree of paranoia among Soviet officials … not unlike the atmosphere of thirty years ago.”

Document 20: Herbert E. Meyer, National Intelligence Council, “Subject: The View from Moscow, November 1983 Undated.” Secret.

Source: Reagan Presidential Library, Fortier Files, Soviet Project [1 of 2], Box 97063.

Herbert E. Meyer, Vice Chairman of the National Intelligence Council, summarized and circulated two views of the uncertainty in Moscow in this 1983 memo, which — as Mark Palmer suggested — was “an attempt to place ourselves in Soviet shoes [and] look at the world as they look at it.”

After presenting a bleak view for the future of the Soviet Union the memo concludes by asking, “What does all this mean for future Soviet actions?” He presented two views: that the Soviet leadership would either “make necessary sacrifices to stay in the game, get their licks in whenever and wherever they can, and count on new successes to come” or, with less likelihood, “the Soviets might consider themselves backed into a corner and lash out dangerously.”

Document 21: For National Security Advisor Robert McFarlane from acting Central Intelligence Agency Director John McMahon, “Subject: Andropov’s Leadership Style and Strategy,” February 3, 1984, Secret.

Source: Central Intelligence Agency Electronic Reading Room.

Acting CIA Director John McMahon and National Security Advisor Robert McFarlane also debated whether the Soviet fear of war was genuine. McMahon asserted that “clearly Andropov has a stake in the ‘appearance’ of bilateral tension as long as it appears that the United States is the offending party. This would not be the first time that Soviet leaders have used international tensions to mobilize their populations,” espousing the view held by some officials — and supported by Andropov’s August 4 Politburo speech — that Soviet leadership did at times attempt to gin up its own population with fear of war for political gain.

Document 22: Series of five interviews with Colonel General Andrian A. Danilevich by John G. Hines, December 18, 1990 to December 9, 1994, in Soviet Intentions 1965-1985: Volume II Soviet Post-Cold War Testimonial Evidence, by John G. Hines, Ellis M. Mishulovich, of BDM Federal, INC. for the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Office of Net Assessment. Unclassified with portions “retroactively” classified.

Source: Defense Department Freedom of Information Act release.

BDM interviews conducted with the Soviet military elite after the USSR’s collapse provide a retrospective glimpse into the minds of the Soviets, whom some U.S. policy makers were trying to understand in 1983.

Andrian Danilevich, a senior military strategist who reported to Marshal Akhromeyev and authored the three-volume Strategy of Deep Operations, “the basic reference document for Soviet strategic and operational nuclear and conventional planning,” told interviewer John Hines of a general fear of war. He recalled “vivid personal memories” and “frightening situations” during “the period of great tension” in 1983, but that there was never a sense of “an immediate threat” of attack within the general staff. The KGB, he said, may have “overstated the level of tension” because they “are generally incompetent in military affairs and exaggerate what they do not understand.”

While recognizing the increased danger of the War Scare, the Soviet General Staff appeared to be less fearful of an imminent American nuclear strike than their KGB counterparts.

Document 23: Interview with Lieutenant General Gelii Viktorovich Batenin by John G. Hines, August 6, 1993 in Soviet Intentions 1965-1985: Volume II Soviet Post-Cold War Testimonial Evidence, by John G. Hines, Ellis M. Mishulovich, of BDM Federal, INC. for the Office of the Secretary of Defense Net Assessment. Unclassified with portions “retroactively” classified.

Source: Defense Department Freedom of Information Act release.

Gelii Batenin, who worked for Marshal Akhromeyev in the General Staff, told interviewers, “I am very familiar with RYaN.” He also confirmed that the situation was tense but that he personally felt no fear of imminent war. “There was a great deal of tension in the General Staff at that time and we worked long hours, longer than usual. I don’t recall a period more tense since the Caribbean Crisis in 1962.”

Document 24: Interview with Colonel General Varfolomei Vladimirovich Korobushin by John G. Hines, December 10, 1992 in Soviet Intentions 1965-1985: Volume II Soviet Post-Cold War Testimonial Evidence, by John G. Hines, Ellis M. Mishulovich, of BDM Federal, INC. for the Office of the Secretary of Defense Net Assessment. Unclassified with portions “retroactively” classified.

Source: Defense Department Freedom of Information Act release.

Varfolomei Korobushin, former Deputy Chief of Staff of Strategic Rocket Forces, recounted the situation as more dire than some of his colleagues remembered: “We in the Central Committee’s Defense Department considered the early 1980s to be a crisis period, a pre-wartime period. We organized night shifts so that there was always someone on duty in the Central Committee. When Pershing IIs were deployed, there appeared the question of what to do with them in case they were in danger of falling into Warsaw Pact hands during a war. These missiles had to be launched. This made them extremely destabilizing. Furthermore, the only possible targets of these missiles was our leadership in Moscow because Pershings could not reach most of our missiles.”

His recollection is more chilling with his revelation that, “it took just 13 seconds to deliver the decision [to launch a nuclear attack] to all of the launch sites in the Soviet Union.”

Document 25: Series of six interviews with Dr. Vitalii Nikolaevich Tsygichko, General Staff Analyst by John G. Hines, December 10, 1990-1991 in Soviet Intentions 1965-1985: Volume II Soviet Post-Cold War Testimonial Evidence, by John G. Hines, Ellis M. Mishulovich, of BDM Federal, INC. for the Office of the Secretary of Defense Net Assessment. Unclassified with portions “retroactively” classified.

Source: Defense Department Freedom of Information Act release.

After acknowledging that “victory” in a nuclear war, even if achieved, would be “meaningless,” Vitalii Tsygichko revealed how a Soviet nuclear launch would progress:

“The plan, which was updated every 6 months, called for Soviet “launch-under-attack” [otvetno-vstrechnyi udar] using all Soviet silo-based systems. This annihilating retaliatory nuclear strike [unichtozhaiushchii otvetno-yadernyi udar] would be directed not against U.S. silos, which Soviet planners assumed would be empty, but rather against military targets (such as airfields, ports, and C3 facilities) and against the U.S. political and economic infrastructure (including transportation grids and fuel supply lines).”

During a 2006 oral history conference he warned that not all Soviets (or Americans) understood the consequences of nuclear war as well as he:

“Among politicians as well as the military, there were a lot of crazy people who would not consider the consequences of a nuclear strike. They just wanted to respond to a certain action without dealing with the ’cause and effect’ problems. They were not seeking any reasonable explanations, but used one selective response to whatever an option was. I know many military people who look like normal people, but it was difficult to explain to them that waging nuclear war was not feasible. We had a lot of arguments in this respect. Unfortunately, as far as I know, there are a lot of stupid people both in NATO and our country.”[17]

Document 26: October 10, 1983, Diary Entry by Ronald Reagan.

Source: The Reagan Diaries Unabridged: Volume 1: January 1981-October 1985, edited by Douglas Brinkley, some information censored by request of the National Security Council.

President Reagan himself came to an epiphany of the unfeasibility of nuclear war during this period. On the morning of Columbus day, October 10, 1983, he watched an advance screening of the television film The Day After, at Camp David. The Day After was a realistic portrayal of nuclear war described by The Washington Post as a “horrific vision of nuclear holocaust.” Reagan wrote in his diary: “It has Lawrence Kansas wiped out in a nuclear war with Russia. It is powerfully done -all $7 mil. worth. It’s very effective & left me greatly depressed.”[18] As Andropov had told Harriman, the leaders of the two superpowers did indeed share a “common denominator:” fear of the danger of “conflict through miscalculation.”

The next War Scare Electronic Briefing Book will rely on documents including a NATO summary and declassified after-action reports to present the most detailed description to date of Able Archer 83, the NATO drill that “practice[d] command and control procedures with a particular emphasis on the transition from purely conventional operations to chemical, nuclear and conventional operations … with three days of ‘low spectrum’ conventional play followed by two days of ‘high spectrum’ nuclear warfare.”

NOTES

[1] Robert Gates, From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider’s Story of Five Presidents and How They Won the Cold War, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2007), 273.

[2] Fritz Ermarth, “Observations on the ” War Scare of 1983 From an Intelligence Perch,” for the Parallel History Project on NATO and the Warsaw Pact, November 6, 2003.

[3] Mark Kramer, “The Able Archer 83 Non-Crisis: Did Soviet Leaders Really Fear an Imminent Nuclear Attack in 1983?;” Thorsten Borring Olesen, “Truth on Demand: Denmark and the Cold War,” in Nanna Hvidt and Hans Mouritzen, ed., Danish Foreign Policy Yearbook 2006, Danish Institute for international Studies, 105; see also Beth A. Fischer’s review of Vojtech Mastny’s “How Able was ‘Able Archer’?” at H-Diplo.

[4] See for instance, Colonel L. V. Levadov, “Itogi operativnoi podgotovki obedinennykh sil NATO v 1983 godu” (Results of the Operational Training of NATO Joint Armed Forces in 1983,”Voyennaya Misl’ (Military Thought), no. 2 (February 1984), 67-76.

[5] One recent paper, ” The Able Archer 83 Non-Crisis: Did Soviet Leaders Really Fear an Imminent Nuclear Attack in 1983?,” relies primarily upon an analysis of Politburo minutes from 1983 and early 1984, (which do not mention “Able Archer 83” or the specific threat of imminent nuclear war), to deduce that the “purported crisis” of 1983 “did not exist at all.” The minutes of these meetings can be found in a donation to the Library of Congress by Soviet general-turned-historian Dmitri Volkogonov, and in “Fond 89,” a collection of documents “submitted to the Constitutional Court of the Russian Federation for the trial of the Soviet Communist Party” in 1992 and published by Stanford University’s Hoover Intuition. One must keep in mind, however, that historians do not yet have access to the minutes of every Politburo meeting from that period. (For that matter, a set of August 4, 1983, minutes included below, but not in the “The Able Archer 83 Non-Crisis” paper, describes Andropov’s instructions to use “all levers” to stop the deployment of Pershing II missiles in Europe.) Most importantly, the key discussions during Andropov’s tenure as General Secretary did not occur in formal Politburo meetings, but at his hospital bedside. According to historian Roy Medvedev’s biography, Andropov would summon his advisors, generals, and Politburo members to his hospital bed to govern the Soviet Union. It was there that Andropov was “fully engaged in the leadership of the country and the army, and the defense of the country,” according to Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov. As such, an examination of sources broader than select Politburo minutes is required to attain the full picture of the Soviet leadership’s views on the 1983 War Scare. Roy A. Medvedev, Neizvestnii Andropov (The Unknown Andropov), (Rostov: Feniks, 1999), 379-382. The Politburo minutes cited in “The Able Archer 83 Non-Crisis” are: May 26, 1983; May 31, 1983; July 7, 1983; September 2, 1983; September 8, 1983; November 15, 1983; November 24, 1983; January 19, 1984; February 10, 1984; February 23, 1984; and March 1, 1984. They can be viewed at the National Security Archive.

[6] Ronald Reagan, The Reagan Diaries Unabridged: Volume 1: January 1981-October 1985, edited by Douglass Brinkley, (New York: HarperCollins, 2009), 333.

[7] Pershing IIs were not deployed to Europe until 23 November 1983, but former CIA analyst Peter Vincent Pry speculates that it is likely that Soviet intelligence believed several Pershing II missiles had been deployed before their announced date. Their impending deployment, along with launch on warning doctrine led to an increased reliance upon human intelligence (as opposed to radar and satellite technology) to monitor for a nuclear attack and the creation of Operation RYaN. Pry, Peter Vincent, War Scare: Russia and America on the Nuclear Brink, (Westport: Praeger, 1999), p. 34.

[8] Robert M. Gates. From the Shadows: The Ultimate Insider’s Story of Five Presidents and How they Won the Cold War (New York: Simon & Shuster, 1996), 114.

[9] Raymond Garthoff, The Great Transition: American-Soviet Relations and the End of the Cold War, (Washington D.C.,: The Brookings Institution, 1994), 173.

[11] Valentin Varennikov, Nepovtorimoe, (Unique) Volume 4, (Moscow: Sovetskii Pisatel’ 2001), 168. Varennikov was also commander of Soviet forces in Afghanistan and later participated in the putsch attempt against Mikhail Gorbachev in 1991.

[12] Christopher Andrew and Oleg Gordievsky, Comrade Kryuchkov’s Instructions: Top Secret Files on KGB Foreign Operations, 1975-1985, (Stanford: Stanford University Press 1991), 67. A quasi-official history of Russian foreign intelligence states that the goal of Operation RYAN was to counter “the real threat to the security of the USSR and Warsaw Pact countries” caused by Western military developments and the introduction of new weapons systems. A.I. Kolpakidi and D.P. Prokhorov, Vneshnyaya razvedka Rossii (The Foreign Intelligence Service of Russia) (Saint Petersburg: Neva, 2001), 80.

[13] Other sources vary the spelling of RYaN. Soviet Ambassador to the United States Anatoly Dobrynin spelled it “ryon.” Another spelling includes the word “suprise:” “VRYAN” “vnezapnoe raketno yadernoe napadenie” —surprise nuclear missile attack. Czech Intelligence referred to the operation as NRJAN. Anatoly Dobrynin, In Confidence: Moscow’s Ambassador to Six Cold War Presidents (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001), 523; Oleg Kalugin, The First Directorate: My 32 Years in Intelligence and Espionage Against the West, (New York: St. Martins, 1994), 302; 9 March 1984, Bulgarian Ministry of Interior; MVR Information re: Results from the work on the improvement of the System for detection of RYAN indications, AMVR, Fond 1, Record 12, File 553, provided by Jordan Baev; Peter Rendek, ” Operation ALAN – Mutual Cooperation of the Czechoslovak Intelligence Service and the Soviet KGB as Given in One of the Largest Leakage Cases of NATO Security Data in the Years 1982 – 1986 .”

[14] Rendek, “Operation ALAN – Mutual Cooperation of the Czechoslovak Intelligence Service and the Soviet KGB as Given in One of the Largest Leakage Cases of NATO Security Data in the Years 1982 – 1986,” Presented at The NKVD/KGB Activities and its Cooperation with other Secret Services in Central and Eastern Europe 1945 – 1989 Conference, Bratislava, 14-16 November 2007.

[15] Markus Wolf with Anne McElvoy, Man without a Face: The Autobiography of Communism’s Greatest Spymaster (New York: Random House, 1997), 222.

[16] Vojtech Mastny, “How Able Was “Able Archer”? Nuclear Trigger and Intelligence in Perspective,” Journal of Cold War Studies, Volume 11, Number 1, Winter 2009, 121.

[17] Jen Hoffenaar and Christopher Findlay, eds., Military Planning for European Theatre Conflict During the Cold War: An Oral History Roundtable Stockholm, 24-25 April 2006,Center for Security Studies ETH Zurich, 161.