The 1961 Massacre of Algerians in Paris: When the Media Failed the Test

A COLLEAGUE of mine in Cairo told me a story a few years ago about a massacre in the streets of Paris. He was a news service reporter at the time of the violence in the French capital – Oct. 17, 1961 – and saw tens of bodies of dead Algerians piled like cordwood in the center of the city in the wake of what would now be called a police riot.

But his superiors at the news agency stopped him from telling the full story then, and most of the world paid little attention to the thin news coverage that the massacre did receive. Even now, the events of that time are not widely known and many people, like myself, had never heard of them at all.

This year is an apt time to recall what happened, and not only because this is the 35th anniversary year of Algerian independence. The continuing civil war in Algeria and the growing violence and racism in France, as well as the appalling slaughters taking place elsewhere in the world, give it a disturbing currency.

Here’s what happened:

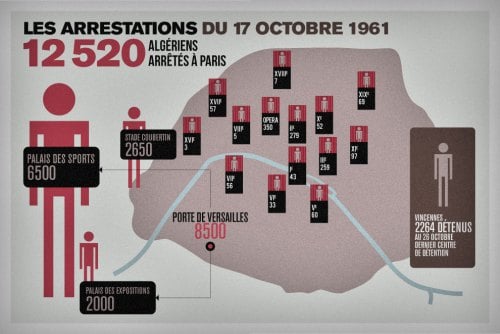

Unarmed Algerian Muslims demonstrating in central Paris against a discriminatory curfew were beaten, shot, garotted and even drowned by police and special troops. Thousands were rounded up and taken to detention centers around the city and the prefecture of police, where there were more beatings and killings.

How many died? No one seems to know for sure, even now. Probably around 200.

It seems astonishing today, from this perspective, that such a thing could happen in the middle of a major Western capital closely covered by the international media. This was not Kabul, Beijing, Hebron or some Bosnian backwater, after all, but the City of Light – Paris.

But the Fifth Republic under President Charles de Gaulle was in trouble in October 1961. De Gaulle, who was primarily interested in establishing France’s pre-eminent position in Western Europe and the world, found himself presiding over domestic chaos. France was constantly disrupted by strikes and protests by farmers and workers, as well as by terrorism from opposing organizations: the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN), representing the Algerian nationalist independence movement, and the Organisation Armée Secrète (OAS), a group of disaffected soldiers, politicians and others committed to keeping Algeria French. The OAS rightly perceived that de Gaulle was bound to free France from the burden of its last major colonial holding, so he could get on with the business of making France the economic and political power of his lofty ambition.

Eyewitness reports recounted stranglings by police.

But the vicious war in Algeria, marked by bloody atrocities committed on all sides, had been grinding on for nearly seven years. Terrorist attacks in Paris and other French cities had claimed dozens of lives of police, provoking what Interior Minister Roger Frey called la juste colère – the just anger – of the police. They vented that anger on the evening of Oct. 17. About 30,000 Muslims – from among some 200,000 Algerians, ostensibly French citizens, living in and around Paris – descended upon the boulevards of central Paris from three different directions. The demonstration of men, women and children was called by the FLN to protest an 8:30 p.m. curfew imposed only on Muslims.

The demonstrators were met by about 7,000 police and members of special Republican Security companies, armed with heavy truncheons or guns. They let loose on the demonstrators in, among other places, Saint Germain-des-Prés, the Opéra, the Place de la Concorde, the Champs Elysée, around the Place de l’Étoile and, on the edges of the city, at the Rond Point de la Defense beyond Neuilly.

My news agency friend counted at least 30 corpses of demonstrators in several piles outside his office near the city center, into which he had pulled some Algerians to get them away from rampaging police. Another correspondent reported seeing police backing unarmed Algerians into corners on sidestreets and clubbing them at will. Later eyewitness reports recounted stranglings by police and the drowning of Algerians in the Seine, from which bodies would be recovered downstream for weeks to come.

Maurice Papon, the Prefect of the Paris police, was the only Vichy France official to be convicted for his role in the deportation of Jews during WW II. But Papon was never prosecuted for the deaths of Algerians caused by police under his orders in 1961. These were not the last deaths caused by police under Papon’s responsibility. Four months later, in February 1962, Papon went too far even for the French President Charles De Gaulle, when French police killed nine white people at a Communist-led demonstration against the war in Algeria. 700,000 people marched at the funeral of the five protesters while a general strike shut down Paris. | AFP/Getty Images

Thousands of Algerians were rounded up and brought to detention centers, where the violence against them continued. “Drowning by Bullets,” a British TV documentary aired about four years ago, alleges that scores of Algerians were murdered in full view of police brass in the courtyard of the central police headquarters. The prefect of police was Maurice Papon, who recently was still denying charges that he was responsible for deporting French Jews to Auschwitz during World War II while he was part of the Vichy government.

The official version

The full horror of this inglorious 1961 episode in French history was largely covered up at the time. Though harrowing personal accounts did eventually percolate to the surface in the French press, the newspapers – enfeebled by years of government censorship and control – for the most part stuck with official figures that only two and, later, five people had died in the demonstration. Government-owned French TV showed Algerians being shipped out of France after the demonstration, but showed none of the police violence.

Journalists had been warned away from coverage of the demonstration and were not allowed near the detention centers.

With few exceptions, the British and American press stuck to the official story, including suggestions that the Algerians had opened fire first. Even the newsman who saw the piles of Algerian corpses was not allowed to report the story; his bosses ordered that the bureau reports stick to the official figures.

Both French and foreign journalists in Paris seemed tacitly to agree that nothing should be done to further destabilize the French government or endanger de Gaulle, who was widely seen as the last, best hope for navigating France out of its troubles.

The story quickly died, drowned out by fresher alarums and excursions in Europe and elsewhere.

And, of course, in the next year, Algeria would have its independence.

Jacques Vergès, the controversial French lawyer who represented the FLN during the war in Algeria, told me in an interview last summer that the police violence and government and press cover-up in 1961 were not surprising. The political circumstances were right for it, and the news media usually do what they’re told. Just look at how easy it was to round up and intern American citizens of Japanese descent after Pearl Harbor, he observed. If he’s right, then the problem for politicians is to make sure that the conditions for injustice and atrocity do not conjoin, that there is no probability created for massacres like the one in Paris in October 1961. And if the politicians fail, then the problem for journalists and others is how to resist becoming their accomplices.

From Washington Report, March 1997, pg. 36

© Washington Report, 1997