Thailand’s Thaksin Regime and The Cambodian Connection

Trail from regime’s thugs leads back to ally and dictator-for-life, Hun Sen of Cambodia.

Late last night, after Thais across the nation celebrated Father’s Day, armed thugs attacked several anti-regime protesters near the currently occupied Ministry of Finance.

They rode motorcycles, fired guns, and threw explosives. There were several injuries, including one protester losing his arm. Protest leaders demanded the regime investigate the incident, and have only been met by silent complicity.

Image: Cambodian dictator-for-life Hun Sen (left) stands next to deposed dictator of Thailand, Thaksin Shinawatra (right), during a round of golf. Cambodia has provided sanctuary for Thaksin’s most extreme political allies, and served as a base of operations form which to destabilize neighboring Thailand. Hun Sen even went as far as officially appointing Thaksin as Cambodia’s “adviser on economics” to bolster his sagging legitimacy. While Thaksin is widely believed to be in exile in Dubai, he divides at least part of his time staying in Cambodia. With militants and thugs from Cambodia turning up behind violence targeting anti-regime protesters, the trail of slime leads to Hun Sen and Thaksin’s door.

The same night, 5 Cambodians were caught attempting to torch the main anti-regime protest stage at Democracy Monument, according to Thai PBS.

While the regime cannot openly confront the protesters with excessive violence in fear of justifying the army to mobilize and oust the regime, it has in the past, and is now resorting to the use of hired thugs and professional mercenaries to carry out deadly attacks in its stead. Regime gunmen have already been photographed and captured on video having triggered the first deadly violence of the protests last week.

With the capture of 5 Cambodians attempting to commit arson, admitting that they were hired to do so, it exposes what might be just the leading edge of a large campaign of violence being organized by the regime. The regime’s ties to the neighboring dictatorship of Hun Sen of Cambodia are well known within Thailand, however little, if ever covered by the Western press.

Cambodia: A Warning of What Thaksin’s Thailand Will Become

Cambodia is ruled by dictator-for-life Hun Sen, who has been in office since 1985, and re consolidated his despotic grip on power in 1997 after a bloody military coup that saw his opponents either killed or exiled. Those who failed to flee, according to Human Rights Watch, were brutally tortured and murdered. Since then, he has presided over a tragically failed state, the victim of the Khmer Rouge, of whom Hun Sen was a participating member, and since then squatted upon by his regime and a large collection of foreign backers.

He is by far one of the most detestable politicians alive on Earth, yet his utility to the West has provided him an international media blackhole in which his crimes and atrocities have been hidden for decades.

This can be explained by the literal selling-out of Cambodia from under the feet of its own people, by Hun Sen to foreign corporate-financier interests.

In the Guardian’s 2008 article titled, “Country for sale,” it is reported that:

Almost half of Cambodia has been sold to foreign speculators in the past 18 months – and hundreds of thousands who fled the Khmer Rouge are homeless once more.

The Guardian further elaborated:

Hun Sen and his ruling Cambodian People’s Party (CPP) have, in effect, put the country up for sale. Crucially, they permit investors to form 100% foreign-owned companies in Cambodia that can buy land and real estate outright – or at least on 99-year plus 99-year leases. No other country in the world countenances such a deal. Even in Thailand and Vietnam, where similar land speculation and profiteering are under way, foreigners can be only minority shareholders.

Today, the Cambodian military is literally being sold off to foreign interests now possessing wide swaths of land as mercenary forces to crush any local opposition. Surely displacing millions, and selling land out from under people is criminal, and an affront to humanity. But strangely enough, this story goes largely unreported, the UN remains eerily silent, and in fact, the United States, as of 2010 has begun training many of the most notorious land-grabbing military units involved in this ongoing atrocity.Indeed, Operation Angkor Sentinel kicked off in July 2010 as US Army troops trained with the local Cambodian troops. The United States shamelessly defended the exercises claiming that:

“Our military relationship is about … working toward effective defence reform, toward encouraging the kind of civil-military relationship that is essential to any healthy political system.”

While the US’ training of Cambodian troops in and of itself does not directly indicate a conspiracy, it positions the US military well for any current or future operations that may be undertaken in support of the US-backed regime in neighboring Thailand.

Enter the Thaksin Shinawatra Regime

Like Hun Sen, Thaksin has a penchant for mass murder, human exploitation, and a proclivity for serving foreign interests. Unlike Hun Sen however, Thaksin’s opponents are stronger, better organized and still hold firmly in their possession most of Thailand’s indigenous institutions. While foreign interests have helped Thaksin by building up NGOs to augment his regime, these still hold very little sway in Thai society.

Back-to-back failed insurrections by Thaksin in 2009 and 2010, after a military coup that ousted Thaksin from power in 2006, saw many of his political allies flee to neighboring Cambodia.

In addition to harboring members of Thaksin’s political machine, Hun Sen went as far as appointing Thaksin himself as a “government adviser on the economy,” in an attempt to bolster his lack of legitimacy.

Amongst those who fled to Cambodia after the 2009-2010 violence was Jakrapob Penkair, a leader of Thaksin’s so-called “red shirt” mob. In an Asia Times report titled, “Plots seen in Thaksin’s Cambodia gambit,” it was stated that:

Before going into exile, Jakrapob told this correspondent that the UDD had clandestinely moved small arms from Cambodia to Thaksin’s supporters in Thailand’s northeastern region, where the exiled premier’s popularity runs strongest. He told other news agencies that the UDD was willing to launch an “armed struggle” to achieve its goals, which included the toppling of the government and restoration of Thaksin’s power.

The report went on to describe possible scenarios for an increasingly militarized attempt by Thaksin to eliminate his enemies, a cue assuredly taken from Hun Sen’s bloody exploits.

Worst Case Scenario – The Syria Model

The number of armed supporters Thaksin could possess in Thailand are minimal. Of the 10,000-30,000 supporters he is able to mobilize with cash payments and bus services at any given time, only about 1,000 could be considered fanatical, and out of that, fewer still who are of military age, willing, and physically able to take up arms against Thaksin’s enemies. Thaksin had clearly augmented this with professional mercenaries, drawn from paramilitary border units in the northeast, but these numbered only about 300 and were easily outmatched by the Thai military in 2010.

Thaksin’s grip on the nation’s police forces allows him to produce on demand thousands from across his north and northeast political stronghold, but even if these police were armed, they lack the training, organizational skills, and coordination to pose any threat to the nation’s armed forces. They have proven in recent days to be completely ineffectual against even unarmed protesters.

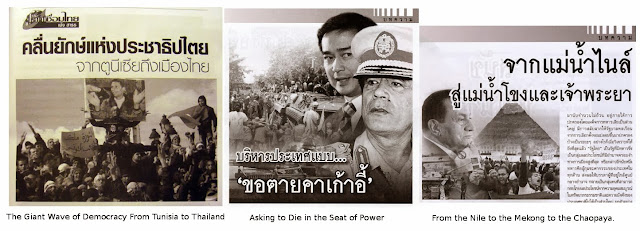

Image: From Thaksin Shinawatra’s “red” publications, left to right – “The Giant Wave of Democracy From Tunisia to Thailand,” “Asking to Die in the Seat of Power,” and “From the Nile to the Mekong, to the Chaopaya,” all indicate that Thaksin’s propagandists were likewise channeling the US State Department’s “Arab Spring” rhetoric as well as making the implicit threat that armed militancy was (and may still be) a desired option.

The real threat would be an influx of Cambodian mercenaries, trained, armed, and directed from Cambodia, and sent into Thailand covertly to be staged and deployed at key points during Thaksin’s continued bid to consolidate his power. These could be used to augment police and small units of fanatics drawn from Thaksin’s “red shirt” mob, or in individual operations aimed at various elements of the opposition.

This follows the same model Thaksin’s foreign backers are using against Syria, where armed militants had been prepared and staged along Syria’s borders, years before violence erupted in 2011. While initial reports from Western media claimed Syria was engaged in a “civil war,” it is now abundantly clear it was instead a foreign invasion by mercenaries sponsored by a conglomerate of NATO and Persian Gulf nations.

However, unlike in Syria, Thailand commands tactical, strategic, economic, and numerical superiority over Cambodia. There are few if any regional mechanisms that would protect the regime in Cambodia from retaliation by Thailand should violence break out and Hun Sen found complicit in supplying mercenaries and/or material support. With Hun Sen facing growing opposition at home against his enduring despotism, he would likely fair poorly against an additional front opened up abroad.

The Thai “civil war” Western analysts have long been predicting with poorly masked enthusiasm, would most likely only materialize using the “Syrian-model” of covert invasion combined with a coordinated propaganda campaign carried out by the Western media. Instead of Jordan, Lebanon, Turkey, and northern Iraq feeding militants into Syria, this new war would consist of Cambodia feeding militants and material in through northeast Thailand, with the resulting conflict appearing to be between Thaksin’s political stronghold there and the rest of the country.

Heading Off Trouble – Using the Egyptian Model

It appears that that Thai military has already been planning to checkmate this option by positioning its forces near the Cambodian border within the context of a long-running border dispute with Phnom Phen.

Exposing plans by the regime to use maximum violence if ousted by another peaceful military coup, and exposing the manufactured nature of this planned violence, diminishes attempts by both the regime and its foreign backers to portray the subsequent mayhem as “the people fighting to restore democracy.”

While the violence would stand little chance of actually defeating Thailand’s formidable military forces, it could serve as useful for securing more overt foreign backing (just as in Syria’s case). By exposing it as a premeditated fraud from the beginning, and comparing it to NATO’s already widely unpopular “covert” intervention in Syria, this option may become altogether distasteful – perhaps enough so to be abandoned entirely.

Other preparations the Thai military would be wise to be making are illustrated by the recent coup in Egypt.

Image: While the Western media attempts to portray the military coup as an antiquated feature of failed states, it has been and always will be an essential “check and balance” of last resort. In Egypt, the military initially bent with the force of foreign-funded political destabilization as part of the “Arab Spring,” bid its time, and when the moment was right, overthrew the West’s proxy-regime of Mohamed Morsi. It did so with decisive and unyielding security operations to permanently uproot the regime’s power, and stem any attempts of triggering armed conflict backed by the West to reclaim power. The “Egyptian Model” may prove instructive for Thailand’s current political crisis.

In the wake of NATO’s proxy invasion of Syria, and because Egypt’s establishment initially bent with the force of US State Department-backed protests during the so-called “Arab Spring,” when the Egyptian military decided to finally oust the resulting Western-installed regime, it quickly decapitated the leadership of its main support base, the Muslim Brotherhood, jailing leaders and ransacking its facilities nationwide, while they quickly severed foreign funding to the insidious NGOs constructed to subvert Egyptian sovereignty.

Attempts to trigger an armed uprising were quickly extinguished with decisive and unyielding security operations. By “tearing off the band-aid quickly,” Egypt was able to restore order. While protests and violence are still present in Egypt, it will never develop into what Syria is now facing, or what Thailand could possibly face.

Nations with any semblance of sovereignty left have surely been studying what the generals in Egypt have done.