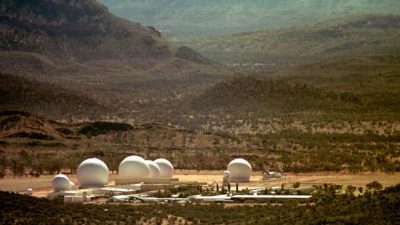

Target Finding for the Empire: The Pine Gap Joint Defense Facility, America’s Spy Hub in the Heart of Australia

“The tasking we get at Pine Gap is look for this particular signal coming out of this particular location. If you find it, report it, and if you find anything else of interest, report that as well.” David Rosenberg, former NSA Team leader, weapon’s analysis at Pine Gap, Aug 20, 2017

At times, there is a lag between the anticipation and the revelation, the assumption that an image might be as gruesome, or perhaps enlightening, as was first assumed. Nothing in the latest Edward Snowden show suggests anything revelatory. They knew it, as did we: that the US military satellite base spat on a bit of Australian dust in a part of the earth that would not make Mars seem out of place, is highly engaged.

Radio National’s Background Briefing made something of a splash on Sunday, with some assistance from the Edward Snowden National Security Agency trove.[1] The documents do much in terms of filling in assumptions on the geolocating role of the facility, much of which had already had some measure of plausibility through the work of Richard Tanter and the late Des Ball.

As Tanter puts it,

“Those documents provide authoritative confirmation that Pine Gap is involved, for example, in the geolocation of cell phones used by people throughout the world, from the Pacific to the edge of Africa.”[2]

“NSA Intelligence Relationship with Australia,” by way of example, discloses the NSA term for the Pine Gap facility, ironically termed RAINFALL. “Joint Defence Facility at Pine Gap (RAINFALL) [is] a site which plays a significant role in supporting both intelligence activities and military operations.”

Another document supplies some detail as to the role of the facility, confirming that it does beyond the mundane task of merely collecting signals. It also does the dirty work analysing them.

“RAINFALL detects, collects, records, processes, analyses and reports on PROFORMA [data on surface-to-air missiles, anti-aircraft artillery and fighter aircraft] signals collected from tasked target entities.”

Pine Gap has always generated a gaping accountability gap of its own, and these Snowden treats affirm the point. Rather than being an entity accountable to the queries and concerns of the local indigenous population; rather than supplying the local members of parliament from the Senate and the lower house briefings about its activities, Pine Gap is hived off from usual channels, a reminder about how truly inconsequential democracy is in the Canberra-Washington alliance.

Pine Gap has always had its platoons of unflinching apologists, and a common theme, apart from the worn notion that the US security umbrella prevails with fortitude, is that the base is genuinely good. In a Central Intelligence Agency’s National Intelligence Daily (Feb 13, 1987), the agency notes with approval the forthcoming Australian Defence white paper indicating strong “support or US-Australian joint defence facilities.”[3]

The publication would dispel any wobbliness on Australian military commitments, a point alluded to by the then minister for defence, Kim Beazley. A further point was to note the “defensive” nature of the facilities, opposition to those “leftwing groups to the contrary.”

So what if Australians in the Northern Territory are ignorant that the communications facility pinpoints targets for drone strikes? We can be assured that these are legitimate, vetted and, when struck, obliterated with fastidious care.

Much of this dressed up bunk is based on the notion, sacrosanct as it is, that drone strikes work. They certain do on a few levels – in galvanising more recruits and liquidating more civilians. Like any military weapon, the hygienic notion of the engineered kill, the surgical operation on the battlefield, is fantasy. If the target so happens to be embedded in an urban setting, one filled with non-combatants, the moral calculus becomes less easy to measure.[4]

The other through-the-glass-darkly feature of the Pine Gap facility lies not only in its geolocation means, but its value as a target. Having such conspicuous yet inscrutable tenants places Australia in harm’s way, a loud invitation to assault.

The CIA was already cognisant of this point in 1987, identifying awareness on the part of Australian defence officials that “the joint facilities would be attacked in a US-Soviet nuclear exchange but argues that removal of the US presence would increase the likelihood of superpower conflict.”[5] The end of the Cold War does little to dispel the significance of Pine Gap as a target of considerable interest.

Where to, then? A firm insistence, for one, that Australia detach itself from the tit of empire, the bosom of Washington’s military industrial complex. This requires something virtually outlawed in Canberra: courage. It has fallen upon such delightfully committed if motley outfits as the Independent and Peaceful Australian Network (IPAN), an organisation of calm determination committed to seeing Australia as something more than the grand real estate for empire.

With each disclosure, with each revelation about Australia’s all too willing complicity in facilitating strikes against foreign targets, many in countries Australians would barely know, the will to change may be piqued. They most certainly will once Australian officials face their first war crimes charges over the use of drones, aiding and abetting their US counterparts in the whole damn awful enterprise.[6]

Dr. Binoy Kampmark was a Commonwealth Scholar at Selwyn College, Cambridge. He lectures at RMIT University, Melbourne. Email: [email protected]

Notes

Featured image is from news.com.au.