Strategic Communications: How NATO Shapes and Manipulates Public Opinion

When NATO forces intervened in Libya last year to help oust Muammar Qaddafi, military planners were aware that one of the greatest battles of the conflict would not be military, but ideological: justifying the legitimacy of their actions to both Libyans and the wider international audience.

NATO’s “strategic communications” framework for the operation informed officials that “Managing the information domain will be critical to NATO’s efforts being understood – and ultimately supported – by the audiences.”

In order to ensure this support, NATO must “use of the full range of information and communication capabilities” to help unify their message and “manage and shape perceptions, to counter potential misinformation and to build public support.”

For international audiences, this meant conveying NATO’s commitment, legitimacy and resolve and being prepared to counter criticisms of its military policies.

If asked about civilian casualties, the framework recommends NATO spokespeople provide “Clear messaging on NATO doing its utmost to carefully target only air related military objectives and avoid civilian casualties.”

If asked about NATO’s credibility in the Arab world, the framework recommends emphasizing the operation’s “legal basis and recognition by the International Community, including Arab League and the Gulf Cooperation Council” while maintaining that “NATO is acting legally and in support of the Libyan people.”

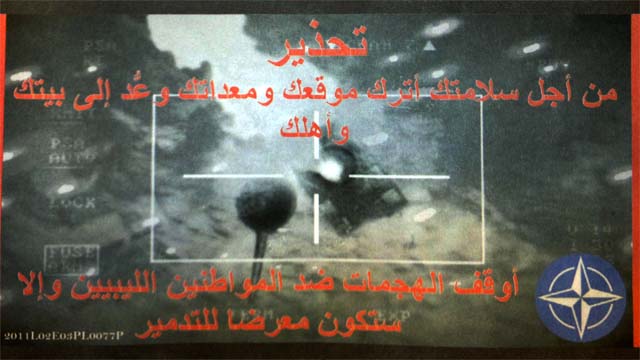

An example of a psychological operations leaflet dropped over Libya by NATO forces during Operation Unified Protector.

For audiences within Libya, strategic communications involved the production of media to influence Qaddafi loyalists to leave their weapons and cease killing civilians.

Leaflets found in Tripoli around August 2011 advised Libyan forces that “many officers and soldiers have chosen to stand against Gaddafi’s orders and refrain from fighting against innocent civilians.”

One side of the leaflet, which bore NATO’s logo, encouraged soldiers to “join these men for a prosperous, peaceful future for Libya” while the opposite side displayed a photo of a Predator drone alongside a tank with a crosshair over it. Amateur radio enthusiasts in Europe and the U.S. were able to listen to NATO broadcasts encouraging Libyan forces to abandon their vehicles and cease fighting. “NATO does not want to kill you,” says a voice inone of the broadcasts, “but if you continue to operate, move, maintain or remain with military equipment of any sort, you will be targeted for destruction.”

Understanding StratCom

A collection of documents recently obtained and published by Public Intelligence provides a complete guide to NATO’s training process for “strategic communications” activities, including public diplomacy, public affairs, information operations and psychological operations. The documents, compiled for participants in a NATO training summit, describe the doctrine behind strategic communications and provide practical examples of their use in a number of recent conflicts from Libya to Afghanistan. These activities are designed to contribute “positively and directly in achieving the successful implementation of NATO operations, missions, and activities” as well as “influence the perceptions, attitudes and behaviour of target audiences . . . with the goal of achieving political or military objectives”. NATO’sStrategic Communications Policy explains the aim of these operations:

Today’s information environment, characterized by a 24/7 news cycle, the rise of social networking sites, and the interconnectedness of audiences in and beyond NATO nations territory, directly affects how NATO actions are perceived by key audiences. That perception is always relevant to, and can have a direct effect on the success of NATO operations and policies. NATO must use various channels, including the traditional media, internet-based media and public engagement, to build awareness, understanding, and support for its decisions and operations.

NATO’s Military Concept for Strategic Communications states that “the vision is to put Strategic Communications at the heart of all levels of military policy, planning and execution” as it is “not an adjunct activity, but should be inherent in the planning and conduct of all military operations and activities.”

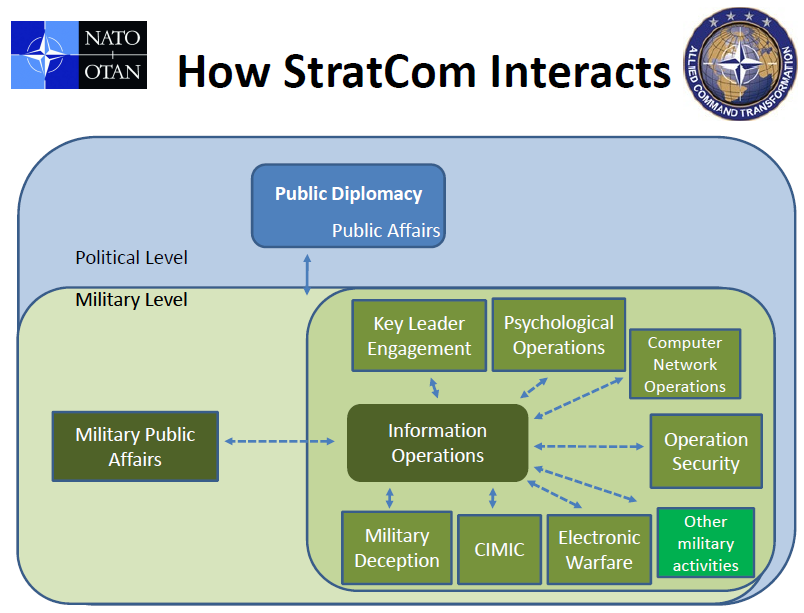

Strategic communications at the political level encompasses both public diplomacy and public affairs, functions designed to communicate facts and information to the public while maintaining credibility. According to NATO’s Allied Command Operations Directive on Public Affairs, “Public support for NATO’s missions and tasks follows from public understanding of how the Alliance makes a difference to international peace and security.” If viewed from an effects-based perspective, the directive states that “enhancing support for the Alliance by maintaining credibility is the effect for the [public affairs] function.” NATO’s Public Diplomacy Strategy for 2010-2011 states the primary goal of communication efforts should be conveying “the values and principles that NATO stands for, first and foremost the principle of Allied solidarity, will feature prominently in NATO’s communication and outreach efforts, in particular towards the young generation.”

A diagram depicting the relationships between various components of NATO’s strategic communications efforts.

At the military level, strategic communications encompasses everything from psychological operations to electronic warfare. Deception operations, computer network operations and even engagement with local leaders all fall under the category of information operations, one of the broadest areas of strategic communications.

NATO’s Bilateral Strategic Command Information Operations Reference Book describes information operations as being increasingly important in modern operations due to the “the complex challenges of the global security environment” which “require consideration and integration of the information factor throughout all processes – analysis, planning, execution and assessment.” Due to the importance of the overall information environment in determining the outcome of a conflict, it is necessary that “all decision-makers at all times appropriately understand the (possible) effects of their actions in the information environment; it is not just about deliberate activity using information through means of communication, it is the combination of words and deeds that delivers the ultimate effect.”

NATO’s documentation on strategic communications acknowledges the increasingly important role that information and perception play in determining the effects of military action. “The employment of any element of power projection, particularly the military element, has always had a psychological dimension,” according to NATO’s 2003 Psychological Operations Policy. This psychological impact is nothing new, but has increasingly broad implications due to the prevalence of modern technology and social media:

PSYOPS have been used throughout history to influence attitudes and behaviours of people, leaders and key communicators. The dense and ubiquitous nature of today’s global information environment, coupled with NATO’s involvement in non-Article 5 Crisis Response Operations, have dramatically increased the demand and importance of effective PSYOPS. In today’s Information Age, NATO can expect to operate for an extended period of time in an area where sophisticated, indigenous media compete for influence over the perceptions of local audiences. The organisation, state, or entity more able to effectively influence the understanding of a crisis or conflict, especially managing the perceptions of particular target audiences, will likely be the most successful. PSYOPS are conducted to convey selected information and indicators to governments, organisations, groups and individuals, with the aim of influencing their emotions, attitudes, motives, perceptions, reasoning and ultimately their behaviour and decisions.

To achieve the desired outcome, strategic communications are integrated directly into NATO’s comprehensive planning process, defining goals and strategies for the various influence activities to be conducted in support of an operation. Strategic communications frameworks for the operation are developed by a working group at NATO headquarters ensuring all aspects of communication, from the diplomatic level to the military information operations on the ground, are coordinated within a unified narrative. After reviewing “NATO strategic and military strategic objectives and effects” NATO’sComprehensive Planning Directive instructs military planners to “assess the impact of military actions on the information environment” and “develop narratives, themes and master messages for different audiences.”

Based on their understanding of the different perspectives and biases of the different audiences, StratCom should develop an over-arching, resonating narrative, upon which themes and master messages can be based. StratCom must then refine the themes and master messages depending on the strategic conditions, taking into account target audience receptiveness, susceptibility and vulnerability to different historical, social, cultural, and religious references.

The directive also recommends that planners “identify and establish required mechanisms to address issues of strategic and/or political importance” such as civilian casualties to protect against the “rapid loss of NATO’s credibility in the theatre and perhaps even within the wider international community.” This may require the involvement of “other international actors, opinion formers and elites” who can be “integrated into this approach through a coordinated engagement strategy at all levels within the wider local, regional and international public to promote support for NATO actions.”

Framing Conflicts

Examining NATO’s strategic communications frameworks for several recent conflicts provides concrete examples of the organization’s efforts to construct and maintain narratives favorable to their military and political objectives.

The frameworks, which are signed by NATO’s Secretary General and sent to diplomatic representatives of allied countries involved in the conflict, detail a core message and various supportive themes designed to promote the narrative advanced by NATO.

For example, the 2011strategic communications framework for Afghanistan emphasizes the themes of resolve and momentum to “maintain Afghan and international support for the continuation of the mission.” The strategic communications framework for NATO’s intervention in Libya emphasizes legitimacy, that NATO is “operating under a clear international legal mandate, in coordination with the Contact Group on Libya, and with broad regional support”, while managing expectations and emphasizing the humanitarian assistance being provided.

Spokespeople play a central role in implementing the strategic communications framework by reinforcing the narratives decided on by NATO officials and countering misinformation. A training presentation for instructing NATO spokespeople in Afghanistan describes how to “control your media environment” by advancing “commercial” messages that support the strategic communications objectives for the conflict.

The presentation lists cosmetic issues for spokespeople, like posture and controlling hand gestures, and even provides bridging phrases such as “First let me say . . .” or “The key issue here is . . .” to bring interviewers back to the spokesperson’s commercial messages.

The presentation also teaches spokespeople how to deflect difficult questions on topics like civilian casualties. If asked about NATO “being responsible for high numbers of civilian casualties”, the presentation recommends countering with a statement about NATO’s effort to minimize civilian casualties “through a variety of measures which calls upon our forces to exercise courageous restraint during operations.”

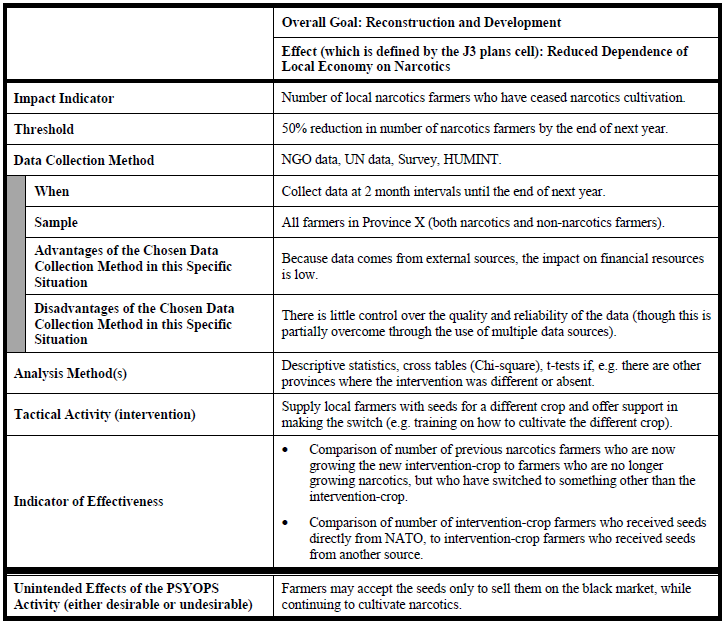

NATO has even worked to develop a framework for assessing the efficacy of activities to influence populations. Over a three year period from 2007-2010, NATO convened multiple research groups with members from the U.S., U.K., Belgium, Netherlands, Sweden, Canada and Germany to formalize a program for measuring the effectiveness of strategic communications activities designed to influence targeted audiences.

The groups authored a report in 2011 called “How to Improve Your Aim: Measuring the Effectiveness of Activities that Influence Attitudes and Behaviors” that assessed NATO’s procedures for determining the success or failure of influence activities in achieving their desired effect. All military operations, including communications functions, are geared towards realizing a particular effect that can be “material, attitudinal or behavioral.”

The report seeks to develop a methodology for monitoring media, conducting surveys and determining the effectiveness of influence operations by tracking specific and quantifiable “impact indicators”. These indicators help determine whether the intended effect is occurring and provide feedback for future operations planning.

Studying and implementing strategic communications has now become an essential component of NATO’s military operations as both a means of influencing populations in theater and abroad. As the development of doctrine for manipulating perceptions continues to become more sophisticated, the ability of the public to discern reality and make decisions becomes increasingly difficult. The information environment, according to NATO’s Allied Joint Doctrine on Information Operations, is “where humans and automated systems observe, orientate, decide and act upon information, and is therefore the principal environment of decision-making.” When governments and militaries make it their fundamental purpose to not simply deceive or manipulate the enemy, but to build and “maintain support” from the very populations that provide them with their funding and mandate, it becomes increasingly difficult for civilian leaders and the public at large to determine the actual reality of a conflict, effectively nullifying their democratic involvement in the prosecution of wars to which they must ultimately pledge their money, their reputations and even their lives.

An example of an “effects matrix” used in planning and assessing psychological operations and other influence activities. The table is presented in a restricted 2011 NATO research report “How to Improve Your Aim: Measuring the Effectiveness of Activities that Influence Attitudes and Behaviors”.