Still Uninvestigated After 50 Years: Did the U.S. Help Incite the 1965 Indonesia Massacre?

It is now fifty years since the so-called “G30S” or “Gestapu” (Gerakan September Tigahpuluh) event of September 30, 1965 in Indonesia, when six members of the Indonesian army general staff were brutally murdered. This event was a decisive moment in Indonesian history: it led to the overthrow of President Sukarno, his replacement by an army general, Suharto, and the subsequent massacre of a half million or more Indonesians targeted as communists.1 It is also forty years since I first wrote to suggest that the United States was implicated in this horrendous event,2 and thirty years since I wrote about it again in 1985 in the Canadian journal Pacific Affairs.3

Strikingly, there has been very little follow-up investigating these events inside the United States. A new generation of scholars, notably John Roosa and Bradley Simpson, have documented U.S. involvement in the exploitation of Gestapu to justify the subsequent mass murder, in the massacre project itself, and in the formation of the subsequent capitalist New Order.4 But there has been, I shall try to show, little or no American response to facts I presented then suggesting U.S. involvement in inciting the specific event of September 30 itself.

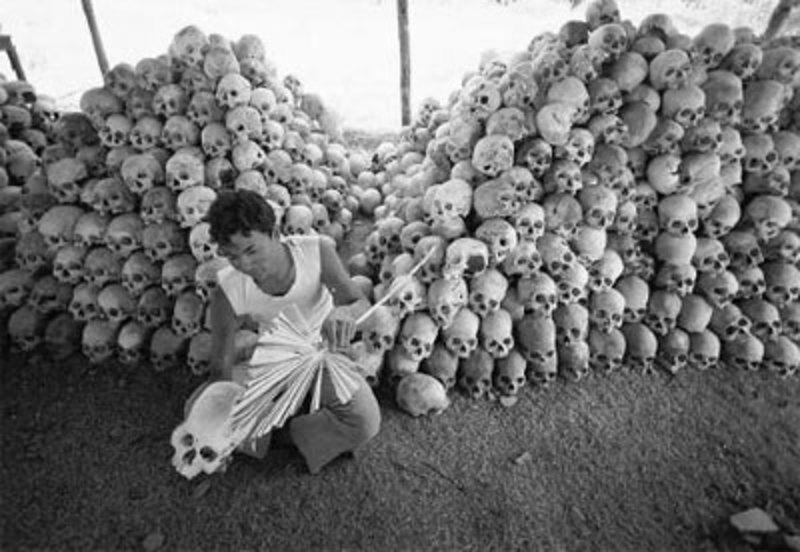

The Indonesia massacre of 1965 The Indonesia massacre of 1965 |

Consider five facts about the U.S. and Indonesia in 1965, facts that (apart from the first) have been little noted or greeted in America with silence.

Fact No. 1) Prior to Gestapu, a number of U.S. academics and policy intellectuals with connections to the CIA and RAND Corporation publicly urged their contacts in the Indonesian Army “to strike, sweep their house clean” (Guy Pauker), while “liquidating the enemy’s political and guerrilla armies” (William Kintner).

Text of my article in Pacific Affairs

In a RAND Corporation book published by Princeton University Press, Pauker, a Rand Corporation analyst and consultant to the National Security Council, urged his contacts in the Indonesian military to assume “full responsibility” for their nation’s leadership, “fulfill a mission,” and hence “to strike, sweep their house clean.”42 [From fn. 43:] William Kintner, a CIA (OPC) senior staff officer from 1950-52, and later Nixon’s ambassador to Thailand, also wrote in favor of “liquidating” the Indonesian Communist Party [PKI] while working at a CIA-subsidized think-tank, the Foreign Policy Research Institute, on the University of Pennsylvania campus.

Documentation in my article for Fact No. 1

Fn. 42. Guy J. Pauker, “The Role of the Military in Indonesia,” in John H. Johnson, ed., The Role of the Military in Underdeveloped Countries (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1962), pp. 222-24. The foreword to the book is by Klaus Knorr, who worked for the CIA while teaching at Princeton. The book was based on papers delivered to a conference at Princeton in 1962 attended by military officers from other third-world countries, including Brazil, whose U.S.-backed army coup in 1964 preceded Indonesia’s by a year.

Fn. 43. William Kintner and Joseph Kornfeder, The New Frontier of War [London: Frederick Muller, 1963], pp. 233, 237-38): “If the PKI is able to maintain its legal existence and Soviet influence continues to grow, it is possible that Indonesia may be the first Southeast Asian country to be taken over by a popularly based, legally elected communist government…. In the meantime, with Western help, free Asian political leaders — together with the military — must not only hold on and manage, but reform and advance while liquidating the enemy’s political and guerrilla armies.”

Reception of Fact No. 1

Googling for “pauker + kintner + indonesia” yields many results. Of the first ten, five are to my work, and five are to works sourcing me. I failed to discover any independent discussion. But this first fact, unlike those following, was relatively widely received, because the quotations from Pauker and Kintner were picked up and reproduced by Noam Chomsky.

Fact No. 2) Gestapu was a false flag operation: it claimed to have acted to defend Sukarno, but the pro-Sukarno generals in the Indonesian Army General Staff were in fact among the first to be assassinated.

Text of my article

According to the Australian scholar Harold Crouch, by 1965 the Indonesian Army General Staff was split into two camps. At the center were the general staff officers appointed with, and loyal to, the army commander General Yani, who in turn was reluctant to challenge President Sukarno’s policy of national unity in alliance with the Indonesian Communist party, or PKI. The second group, including the right-wing generals Nasution and Suharto, comprised those opposed to Yani and his Sukarnoist policies.5 All of these generals were anti-PKI, but by 1965 the divisive issue was Sukarno.

The simple (yet untold) story of Sukarno’s overthrow is that in the fall of 1965 Yani and his inner circle of generals were murdered, paving the way for a seizure of power by right-wing anti-Yani forces allied to Suharto. The key to this was the so-called Gestapu coup attempt which, in the name of supporting Sukarno, in fact targeted very precisely the leading members of the army’s most loyal faction, the Yani group.6 An army unity meeting in January 1965, between “Yani’s inner circle” and those (including Suharto) who “had grievances of one sort or another against Yani,” lined up the victims of September 30 [the Yani faction] against those who came to power after their murder [the anti-Yani faction including Suharto].7 Not one anti-Sukarno general was targeted by Gestapu, with the obvious exception of General Nasution.8 But by 1961 the CIA operatives in Washington had become disillusioned with Nasution as a reliable asset, because of his “consistent record of yielding to Sukarno on several major counts.”9 Relations between Suharto and Nasution were also cool, since Nasution, after investigating Suharto on corruption charges in 1959, had transferred him from his command.10

The duplicitous distortions of reality, first by Lt. Colonel Untung’s statements for Gestapu, and then by Suharto in “putting down” Gestapu, are mutually supporting lies.11

Fn. 5. Harold Crouch, The Army and Politics in Indonesia (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1978), pp. 79-81.

Documentation for Fact No. 2

Fn. 6. In addition, one of the two Gestapu victims in Central Java (Colonel Katamso) was the only non-PKI official of rank to attend the PKI’s nineteenth anniversary celebration in Jogjakarta in May 1964: Mortimer, Indonesian Communism, p. 432.5Ironically, the belated “discovery” of his corpse was used to trigger off the purge of his PKI contacts.

Fn. 7. Four of the six pro-Yani representatives in January were killed along with Yani on October 1. Of the five anti-Yani representatives in January, we shall see that at least three were prominent in “putting down” Gestapu and completing the elimination of the Yani-Sukarno loyalists (the three were Suharto, Basuki Rachmat, and Sudirman of SESKOAD, the Indonesian Army Staff and Command School): Crouch,The Army, p. 81n.

Fn. 8. While Nasution’s daughter and aide were murdered, he was able to escape without serious injury and supported the ensuing purge.

Fn. 9. Indonesia, 22 (October 1976), p. 165 (CIA Memorandum of 22 March 1961 from Richard M. Bissell, Attachment B). By 1965 Washington’s disillusionment with Nasution was heightened by Nasution’s deep opposition to the U.S. involvement in Vietnam.

Reception of Fact No. 2

Not mentioned, as far as I know, in the United States.

Fact No. 3) The Johnson Administration misled members of the 88th US Congress, in order to continue aid to the Indonesian army following a Senate amendment prohibiting it.

Footnote 75 to my article: A Senate amendment in 1964 to cut off all aid to Indonesia unconditionally was quietly killed in conference committee, on the misleading ground that the Foreign Assistance Act “requires the President to report fully and concurrently to both Houses of the Congress on any assistance furnished to Indonesia” (U.S. Cong., Senate, Report No. 88-1925, Foreign Assistance Act of 1964, p. 11). In fact the act’s requirement that the president report “to Congress” applied to eighteen other countries, but in the case of Indonesia he was to report to two Senate Committees and the speaker of the House: Foreign Assistance Act, Section 620(j).

Text of my article: After March 1964, when Sukarno told the U.S., “go to hell with your aid,” it became increasingly difficult to extract any aid from the U.S. congress: those persons not aware of what was developing found it hard to understand why the U.S. should help arm a country which was nationalizing U.S. economic interests, and using immense aid subsidies from the Soviet Union to confront the British in Malaysia.

Thus a public image was created that under Johnson “all United States aid to Indonesia was stopped,” a claim so buttressed by misleading documentation that competent scholars have repeated it.74 In fact, Congress had agreed to treat U.S. funding of the Indonesian military as a covert matter, restricting congressional review of the president’s determinations on Indonesian aid to two Senate committees, and the House Speaker, who were concurrently involved in oversight of the CIA.75

Ambassador Jones’ more candid account admits that “suspension” meant “the U.S. government undertook no new commitments of assistance, although it continued with ongoing programs…. By maintaining our modest assistance to [the Indonesian Army and the police brigade], we fortified them for a virtually inevitable showdown with the burgeoning PKI.”76

Only from recently released documents do we learn that new military aid was en route as late as July 1965, in the form of a secret contract to deliver two hundred Aero-Commanders to the Indonesian Army: these were light aircraft suitable for use in “civic action” or counterinsurgency operations, presumably by the Army Flying Corps whose senior officers were virtually all trained in the U.S.77

Marshall Green, U.S. Ambassador to Jakarta in 1965, said to have approved lists of candidates for the purge Marshall Green, U.S. Ambassador to Jakarta in 1965, said to have approved lists of candidates for the purge |

Documentation for Fact No. 3

Fn. 74. The New York Times, August 5, 1965, p. 3; cf. Nishihara, The Japanese, p. 149; Mrázek, vol. II, p. 121.

Fn. 75. A Senate amendment in 1964 to cut off all aid to Indonesia unconditionally was quietly killed in conference committee, on the misleading ground that the Foreign Assistance Act “requires the President to report fully and concurrently to both Houses of the Congress on any assistance furnished to Indonesia” (U.S. Cong., Senate, Report No. 88-1925, Foreign Assistance Act of 1964, p. 11). In fact the act’s requirement that the president report “to Congress” applied to eighteen other countries, but in the case of Indonesia he was to report to two Senate Committees and the speaker of the House: Foreign Assistance Act, Section 620(j).

Fn. 76. Jones, Indonesia: The Possible Dream, p. 324.

Fn. 77. U.S., Congress, Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations, Multinational Corporations and United States Foreign Policy, Hearings (cited hereafter as Church Committee Hearings), 94th Cong., 2nd Sess., 1978, p. 941; Mrázek, The United States, vol. II, p. 22. Mrázek quotes Lt. Col. Juono of the corps as saying that “we are completely dependent on the assistance of the United States.”

Cf. Fn. 43: [A] memo to President Johnson from Secretary of State Rusk, on July 17, 1964, makes it clear that at that time the chief importance of MILTAG was for its contact with anti-Communist elements in the Indonesian Army and its Territorial Organization: “Our aid to Indonesia … we are satisfied … is not helping Indonesia militarily. It is however, permitting us to maintain some contact with key elements in Indonesia which are interested in and capable of resisting Communist takeover. We think this is of vital importance to the entire Free World” (Declassified Documents Quarterly Catalogue, 1982, 001786 [DOS Memo for President of July 17, 1964; italics in original]).

Reception of Fact No, 3

A Google search for “Indonesia + Senate Report No. 88-1925” (the Foreign Assistance Act of 1964) yields seven results, five in English and two in German. All seven are to my 1985 article in Pacific Affairs.

Fact No. 4) In May 1965, months before the September coup, CIA-related Lockheed payments shifted from a Sukarno backer to a Suharto backer.6

|

It is now generally accepted that (as Tim Weiner documents in the case of Japan), “Instead of passing suitcases filled with cash in four-star hotels, the CIA used trusted American businessmen as go-betweens to deliver money to benefit its allies. Among these were executives from Lockheed, the company then building the U-2.”7

Text of my article

From as early as May 1965, U.S. military suppliers with CIA connections (principally Lockheed) were negotiating equipment sales with payoffs to middlemen, in such a way as to generate payoffs to backers of the hitherto little-known leader of a new third faction in the army, Major-General Suharto — rather than to those backing Nasution or Yani, the titular leaders of the armed forces. Only in the 1980s was it confirmed that secret funds administered by the U.S. Air Force (possibly on behalf of the CIA) were laundered as “commissions” on sales of Lockheed equipment and services, in order to make political payoffs to the military personnel of foreign countries.85

A 1976 Senate investigation into these payoffs revealed, almost inadvertently, that in May 1965, over the legal objections of Lockheed’s counsel, Lockheed commissions in Indonesia had been redirected to a new contract and company set up by the firm’s long-time local agent or middleman.86 Its internal memos at the time show no reasons for the change, but in a later memo the economic counselor of the U.S. Embassy in Jakarta is reported as saying that there were “some political considerations behind it.”87 If this is true, it would suggest that in May 1965, five months before the coup, Lockheed had redirected its payoffs to a new political eminence, at the risk (as its assistant chief counsel pointed out) of being sued for default on its former contractual obligations.

The Indonesian middleman, August Munir Dasaad [Agus Musin Dassad], was “known to have assisted Sukarno financially since the 1930’s.”88 In 1965, however, Dasaad was building connections with the Suharto forces, via a family relative, General Alamsjah, who had served briefly under Suharto in 1960, after Suharto completed his term at SESKOAD. Via the new contract, Lockheed, Dasaad and Alamsjah were apparently hitching their wagons to Suharto’s rising star:

When the coup was made during which Suharto replaced Sukarno, Alamsjah, who controlled certain considerable funds, at once made these available to Suharto, which obviously earned him the gratitude of the new President. In due course he was appointed to a position of trust and confidence and today Alamsjah is, one might say, the second important man after the President.89

Thus in 1966 the U.S. Embassy advised Lockheed it should “continue to use” the Dasaad-Alamsjah-Suharto connection.90

Documentation for Fact No. 4

Fn. 85. San Francisco Chronicle, October 24, 1983, p. 22, describes one such USAF-Lockheed operation in Southeast Asia, “code-named ‘Operation Buttercup’ that operated out of Norton Air Force Base in California from 1965 to 1972.” For the CIA’s close involvement in Lockheed payoffs, cf. Anthony Sampson, The Arms Bazaar (New York: Viking, 1977), pp. 137, 227-28, 238.

Fn. 86. Church Committee Hearings, pp. 943-51.

Fn. 87. Ibid., p. 960.

Fn. 88. Nishihara, The Japanese, p. 153.

Fn. 89. Lockheed Aircraft International, memo of Fred C. Meuser to Erle M. Constable, 19 July 1968, in Church Committee Hearings, p. 962.

Fn. 90. Ibid., p. 954; cf. p. 957. In 1968, when Alamsjah suffered a decline in power, Lockheed did away with the middleman and paid its agents’ fees directly to a group of military officers (pp. 342, 977).

Fn. 91. Church Committee Hearings, p. 941; cf. p. 955.

|

Reception of Fact No. 4

Googling for “Lockheed + August Munir Dasaad” yields 207 results, only one more than if you google for “’Peter Dale Scott’ + ‘August Munir Dasaad.’” All the hits are either directly to my work, in Indonesian, or both. Of the first fifteen results for “Lockheed + Alamsjah,” two are irrelevant and the rest are to my work.

Fact No. 5) The Lockheed payment was paralleled, two months before Gestapu, by a similar payoff to Suharto’s business associate Bob Hasan, on a US military contract involving Rockwell Aero-commanders

Text of my article

In July 1965, at the alleged nadir of U.S.-Indonesian aid relations, Rockwell-Standard had a contractual agreement to deliver two hundred light aircraft (Aero-Commanders) to the Indonesian Army (not the Air Force) in the next two months.91Once again the commission agent on the deal, Bob Hasan, was a political associate (and eventual business partner) of Suharto.92 More specifically, Suharto and Bob Hasan established two shipping companies to be operated by the Central Java army division, Diponegoro. This division, as has long been noticed, supplied the bulk of the personnel on both sides of the Gestapu coup drama — both those staging the coup attempt, and those putting it down. And one of the three leaders in the Central Java Gestapu movement was Lt. Col. Usman Sastrodibroto, chief of the Diponegoro Division’s “section dealing with extramilitary functions.”93

Thus of the two known U.S. military sales contracts from the eve of the Gestapu Putsch, both involved political payoffs to persons who emerged after Gestapu as close Suharto allies.

Documentation for Fact No. 5

Fn. 91. Church Committee Hearings, p. 941; cf. p. 955.

Fn. 92. Southwood and Flanagan, Indonesia: Law, p. 59.

Fn. 93. Crouch, The Army, p. 114.

Reception of Fact No. 5

A Google Books search for “Rockwell + 1965 + ‘Bob Hasan’” yields 201 results, mostly in Indonesian (Bahasa Indonesia). Of the first nine, all four of the hits in English, and at least one hit in Indonesian, are to my 1985 article in Pacific Affairs.

|

Insert picture with caption] Bob Hasan, Suharto’s business associate, who received U.S. payoffs on the eve of Gestapu

Reception in general of these facts, and of my article

To my knowledge, I am not aware that any of the above facts (other than the first, picked up by Noam Chomsky) have been discussed in any American source, or indeed in any countries other than Indonesia, even since 1998.

As for my article, I am aware of two academic references to it in the United States before Suharto’s ouster in 1998. Along with other works by Benedict Anderson, Ruth McVey, and Ralph McGehee, it was cited in a single footnote as part of an article by H. W. Brands, “The Limits of Manipulation: How the United States Didn’t Topple Sukarno,” in the Journal of American History, (December 1989).

Brands did not mention the arguments for U.S. involvement. Instead his claim (that

“In fact, Sukarno’s overthrow had little to do with American machinations”) relied on documents in the LBJ library: “The story they tell,” he assured readers, “does render largely untenable the notion that Sukarno’s demise and the accompanying bloodbath originated in the USA.”8 His method, in short, was to trust what U.S. government documents said on the topic, a naïve method that I fear one finds all too frequently among what I call archival historians. Brands concedes that “Certain communications remain classified [and] some may have been consigned to the shredder” (p. 788). But he writes as if unaware that the CIA is quite capable of falsifying releases of its own internal records, when it serves to protect operational secrecy from outsiders.9

The same naïve method marks the only other response (as far as I know) to my argument, this in a book by the journalist Victor Fic implicating China in Gestapu (and published in India):

Peter Dale Scott is the leading theorist about the alleged American role in this conspiracy…. However CIA and other documents declassified and published by the Government of the United States… render Scott’s theory implausible as the CIA, by its own admission, did not have assets in Indonesia to carry out such a ‘coup’ to depose Sukarno or destroy the PKI.10

Fic’s argument deserves a little more attention, since he also refers to an editorial in support of Gestapu which appeared in the October 2, 1965, issue of the PKI newspaper Harian Rakjat. Once again, if taken at face value, this support for the generals’ murder from a Communist paper would seem to corroborate that Gestapu was, as Fic claimed, a left-wing putsch attempt.

However Fic simply ignored the arguments referred to in my essay that the Harian Rakjat “editorial” was in fact a propaganda forgery, perhaps from the CIA. As I quoted then from Anderson and McVey:

Professors Benedict Anderson and Ruth McVey, who have questioned the authenticity of this issue, have also ruled out the possibility that the newspaper was “an Army falsification,” on the grounds that the army’s “competence … at falsifying party documents has always been abysmally low.”115

The questions raised by Anderson and McVey have not yet been adequately answered. Why did the PKI show no support for the Gestapu coup while it was in progress, then rashly editorialize in support of Gestapu after it had been crushed? Why did the PKI, whose editorial gave support to Gestapu, fail to mobilize its followers to act on Gestapu’s behalf? Why did Suharto, by then in control of Jakarta, close down all newspapers except this one, and one other left-leaning newspaper which also served his propaganda ends?116 Why, in other words, did Suharto on October 2 allow the publication of only two Jakarta newspapers, two which were on the point of being closed down forever?

Fn. 115. Anderson and McVey, A Preliminary Analysis of the October 1, 1965, Coup in Indonesia (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1971)], p. 133.

Fn. 116. Benedict Anderson and Ruth McVey, “What Happened in Indonesia?” New York Review of Books, June 1, 1978, p. 41; personal communication from Anderson. A second newspaper, Suluh Indonesia, told its PNI readers that the PNI did not support Gestapu, and thus served to neutralize potential opposition to Suharto’s seizure of power.

|

How to Explain the Fifty Years of Silence?

It is obvious why American Indonesianists were reluctant to mention my article or to investigate the avenues that it opened up as long as Suharto was in power: their careers depended on the ability to visit the country they wrote about. Professor Benedict Anderson at Cornell, was one of the first scholars to question the official account of Gestapu, in the so-called Cornell Report of 1971.11 Later he was famously turned back in Jakarta airport, even though he had arrived on a valid visa.

Another obvious reason is methodological. Diplomatic historians are accustomed to work with government records, rather than concern themselves (as I did) with released internal documents from companies like Lockheed which, in my analysis, operate as part of the American deep state.12

Recently, in an essay that explicitly noted CIA involvement in the 1958 Permesta rebellion, Anderson acknowledged U.S. support in 1965 for the violent response to Gestapu, but as distinguished from Gestapu itself.13 Bradley Simpson, in a definitive account of that support, says of Gestapu itself only that “American historians in particular [he cites my essay in an endnote] have spilled much ink on the question of Washington’s involvement.”14 Today it has become common to see discussion of U.S. involvement in targeting PKI members after Gestapu, as well as in the general repression that followed Gestapu.15 But one does not yet see much discussion of U.S. involvement in Gestapu itself.

My article’s reception outside the United States has been quite different. Published first in Canada in 1985, it was subsequently translated and/or published in Amsterdam (1985, in Dutch), Paris (1986), West Berlin (1988, in Bahasa Indonesia), Hull, England (1990), and since then, starting in 1998, at least six other times in Bahasa Indonesia, inside Indonesia itself.16

I am in no position to estimate the reception in Indonesia of the article (it was actually published there as a book). A sign that the bootleg 1988 translation from West Berlin was being circulated clandestinely in Indonesia is the fact that the book was officially banned by Suharto’s Bureau of Censorship.17 To this day. to my knowledge, the only newspaper reference anywhere to my hypothesis of U.S. involvement in Gestapu was in the English-language Jakarta Post of July 25, 2013.18

Now that Indonesia itself is becoming more open to discussions of Gestapu and its aftermath, it is high time for a similar change of attitude in the United States. And internationally.

|

Epilogue

My views on Sukarno’s overthrow have evolved since the 1980s. In that era, seeing Sukarno in contrast to the repressive dictator Suharto, I described Sukarno as “an undeniably popular and reasonably constitutional civilian leader.”19 Today I recognize that in the last years of his rule the country was becoming more and more unstable, major economic problems were not being addressed, and Sukarno sought to placate public unrest by an ill-advised military campaign against his neighbor Malaysia.

I also attribute greater importance to the fact that Sukarno thus contributed unwittingly to his own downfall, since the secret army special operations unit OPSUS, created by Suharto to handle a peace initiative towards Malaysia of which Sukarno knew nothing, evolved into part of the apparatus plotting for his removal, perhaps indeed the planning core of it.20

Although my 1985 article mentioned OPSUS only in a footnote, I now suspect it may have supplied the milieu for a second coup-minded plot, piggy-backed within the first. I mean by this that there was at first an OPSUS plot, pushed by Suharto and sanctioned by Yani, to negotiate peace with Malaysia against Sukarno’s wishes; but then some of the people conspiring may have had a second agenda, to purge (by means of the false-flag pretext of Gestapu) the army general staff of Yani and other overall Sukarno loyalists, thus clearing the way for the coup and the massacre. Such a sophisticated two-level plot, like the propaganda forgery of the Harian Rakjat “editorial,” may have been beyond the capabilities of Indonesians acting alone.21

Piggy-backed plots are however are a staple of the CIA, and before them of the British MI6. And in 1965 the British Foreign Office, working with MI6, sent its top propaganda expert, Norman Reddaway, to Singapore. In 1998, shortly before his death, Reddaway went public, to describe how “the overthrow of Sukarno was one of the Foreign Office’s ‘most successful’ coups, which they have kept a secret until now:”

A covert operation and psychological warfare strategy was instigated, based at Phoenix Park, in Singapore, the British headquarters in the region. The MI6 team kept close links with key elements in the Indonesian army through the British Embassy. One of these was Ali Murtopo, later General Suharto’s intelligence chief, and MI6 officers constantly travelled back and forth between Singapore and Jakarta.22

Stephen Dorril’s book MI6 confirms that “In South-East Asia MI6 was working hand in glove with the CIA to ‘liquidate’ Indonesia’s President Sukarno.”23

In the same period Ali Murtopo, the head of OPSUS, also traveled back and forth, not just to negotiate clandestinely with the Malaysian government, but also to smuggle “rubber and other goods” to generate money for OPSUS and accumulate $17 million in banks in Singapore and Malaysia.24 Yani had authorized Murtopo’s clandestine MI6 contacts; he would have no way of knowing if these talks had turned to plans to eliminate Yani himself.

Like his close ally Suharto, Murtopo rose up through the Diponegoro Divisision, the division which played a central role both in staging Gestapu, and also in putting it down.25 As I wrote in 1985:

From the pro-Suharto sources — notably the CIA study of Gestapu published in 1968 — we learn how few troops were involved in the alleged Gestapu rebellion, and, more importantly, that in Jakarta as in Central Java the same battalions that supplied the “rebellious” companies were also used to “put the rebellion down.” Two thirds of one paratroop brigade (which Suharto had inspected the previous day) plus one company and one platoon constituted the whole of Gestapu forces in Jakarta; all but one of these units were commanded by present or former Diponegoro Division officers close to Suharto; and the last was under an officer who obeyed Suharto’s close political ally, Basuki Rachmat.17

Two of these companies, from the 454th and 530th battalions, were elite raiders, and from 1962 these units had been among the main Indonesian recipients of U.S. assistance.18 This fact, which in itself proves nothing, increases our curiosity about the many Gestapu leaders who had been U.S.-trained. The Gestapu leader in Central Java, Saherman, had returned from training at Fort Leavenworth and Okinawa shortly before meeting with Untung and Major Sukirno of the 454th Battalion in mid-August 1965.19 As Ruth McVey has observed, Saherman’s acceptance for training at Fort Leavenworth “would mean that he had passed review by CIA observers.”20

Fn. 17. CIA Study, p. 2; cf. p. 65: “At the height of the coup … the troops of the rebels [in Central Java] were estimated to have the strength of only one battalion; during the next two days, these forces gradually melted away.”

Fn. 18. Rudolf Mrázek, The United States and the Indonesian Military, 1945-1966 (Prague: Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences, 1978), vol. II, p. 172. These battalions, comprising the bulk of the 3rd Paratroop Brigade, also supplied the bulk of the troops used to put down Gestapu in Jakarta. The subordination of these two factions in this supposed civil war to a single close command structure under Suharto is cited to explain how Suharto was able to restore order in the city without gunfire. Meanwhile out at the Halim air force base an alleged gun battle between the 454th (Green Beret) and RPKAD (Red Beret) paratroops went off “without the loss of a single man” (CIA Study, p. 60). In Central Java, also, power “changed hands silently and peacefully,” with “an astonishing lack of violence” (CIA Study, p. 66).

Fn. 19. Ibid., p. 60n; Arthur J. Dommen, “The Attempted Coup in Indonesia,” China Quarterly, January-March 1966, p. 147. The first “get-acquainted” meeting of the Gestapu plotters is placed in the Indonesian chronology of events from “sometimes before August 17, 1965”; cf. Nugroho Notosusanto and Ismail Saleh, The Coup Attempt of the “September 30 Movement” in Indonesia (Jakarta: [Pembimbing Masa, 1968], p. 13); in the CIA Study, this meeting is dated September 6 (p. 112). Neither account allows more than a few weeks to plot a coup in the world’s fifth most populous country.

Fn. 20. Mortimer, Indonesian Communism, p. 429.

I would now suspect, admittedly without proof, that if one wanted to research CIA and/or MI6 input into the 1965 Gestapu plot, the MI6/Ali Murtopo connection would be a good place to begin.

In other words, my opinion of Sukarno and his downfall has somewhat changed. However, I continue to view as monstrous the criminal plans made 50 years ago to eliminate both him and the PKI through bloodshed, even if we concede that the actual massacre may have gone way beyond whatever had been planned.

Looking back, we can see the last century as a period when a number of new great powers emerged, and every one of them, not just the United States, have had a lot of innocent blood to account for. To understand U.S. policy in postwar Asia it is essential to determine the exact process by which the criminal decisions surrounding Gestapu were made and to examine them in light of covert interventions elsewhere.

The purpose of investigating the September 1965 event is not to punish its perpetrators, most of whom are now dead. It is to determine what forces capable of such a plot still exist, including in the United States and Indonesia, and to strive to reduce the probabilities of such crimes occurring again in the future.

Peter Dale Scott is a former Canadian diplomat and English Professor at the University of California, Berkeley. His latest book is The American Deep State: Wall Street, Big Oil, and the Attack on U.S. Democracy, published by Rowman & Littlefield. He is also the author ofDrugs Oil and War, The Road to 9/11, The War Conspiracy: JFK, 9/11, and the Deep Politics of War, and American War Machine: Deep Politics, the CIA Global Drug Connection and the Road to Afghanistan. A contributing editor of the Asia-Pacific Journal, his website, which contains a wealth of his writings, is here.

Related articles

• Benedict Anderson, Impunity and Reenactment: Reflections on the 1965 Massacre in Indonesia and its Legacy

• Geoffrey Gunn, Suharto Beyond the Grave: Indonesia and the World Appraise the Legacy

Notes

1 Death estimates are discussed by Robert Cribb, and compacted into an assessment of “as low as 200,000 or as high as one million.” Robert Cribb, “Unresolved Problems in the Indonesian Killings of 1965–1966,” Asian Survey, July/August 2002, p. 559).

2 Peter Dale Scott, “Exporting Military Economic Development: America and the Overthrow of Sukarno, 1965-67,” in Malcolm Caldwell (ed.), Ten Years’ Military Terror in Indonesia (Nottingham: Spokesman Books, 1975), pp. 209-61.

3 Peter Dale Scott, “Exporting Military-Economic Development,” in Malcolm Caldwell, ed., Ten Years’ Military Terror in Indonesia(Nottingham, England: Spokesman Books, 1975), pp. 227-61; “The United States and the Overthrow of Sukarno, 1965-1967,” Pacific Affairs (Vancouver, B.C.) 58.2 (Summer 1985), pp. 239-64.

4 John Roosa, Pretext for Mass Murder: the September 30th Movement and Suharto’s Coup d’état in Indonesia (Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006); Bradley R. Simpson, Economists with Guns: Authoritarian Development and U.S.-Indonesian Relations, 1960-1968 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008).

5 For full citations of this and other sources in these footnotes, see the text of my article at Scott, “The United States and the Overthrow of Sukarno, 1965-1967”.

6 This has been partially corroborated by Andrew Feinstein, but without reference to the 1965 shift in middlemen. See Andrew Feinstein,The Shadow World: Inside the Global Arms Trade (New York: Picador, 2012), pp. 265-66: “In Indonesia in 1965, Lockheed disbursed bribes of $100,000 per plane. However, soon afterwards the CIA assisted the right-wing General Suharto to overthrow the Sukarno government. Lockheed worried that its agent, Isaak [sic] Dasaad, might not be sufficiently well connected to the new regime to be of use. Illustrating the extent of US government complicity in controversial foreign arms sales, the company’s marketing executive noted that a Lockheed official ‘went to the US embassy in Jakarta and asked them specifically whether Dasaad could continue, under the new regime, to be of value to Lockheed’. The embassy said yes, leading Lockheed to record that ‘apparently Dasaad has made the transition from Sukarno to Suharto in good shape.’” Cf. Wimanjaya K. Liotohe, Prima Dosa: Wimanjaya dan rakyat Indonesia menggugat imperium Suharto (Pasarminggu: Yayasan Eka Fakta Kata, 1993).

7 Tim Weiner, Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA (New York: Doubleday, 2007), p. 119. Lockheed money in Japan went to Sasakawa Ryoichi, a CIA agent of influence, and his friend Kodama Yoshio. In my 1965 essay I noted that Sasakawa had “boasted that he played a role in the coup that overthrew Sukarno.” The Lockheed funds to Sasakawa in Japan were partly handled by a Japanese American, Shig Katayama, whose ID Corp. in the Cayman Islands did unexplained business with the CIA-related Castle Bank in the Bahamas.

8 H. W. Brands, “The Limits of Manipulation: How the United States Didn’t Topple Sukarno,” Journal of American History, Vol. 76, No. 3 (Dec., 1989), pp. 785-808 (p. 787). Brands sees Johnson’s policy before his election, while still lacking “a personal political mandate,” as a modest mélange between desires to appease Sukarno, and “quiet efforts to encourage action by the army against the PKI” (pp. 791, 793). I believe he understates the importance of these “quiet efforts,” which (as noted above in discussion of Fact No. 3) a memo from Secretary of State Rusk described on July 17, 1964 as “of vital importance to the entire Free World.” And I know of no evidence for or against his claim that Gestapu caught the CIA “by surprise” (p. 787).

9 For an example, see Peter Dale Scott, Oswald, Mexico, and Deep Politics: Revelations from the CIA Records on the Assassination of JFK(New York: Skyhorse, 2013), pp. 28-29.

10 Victor M. Fic, Anatomy of the Jakarta Coup, October 1, 1965: The Collusion with China Which Destroyed the Army Command, President Sukarno and the Communist Party of Indonesia (New Delhi: Abhinav Publications, 2004), p. 3.

11 B. R. O’G. Anderson and Ruth McVey, A Preliminary Analysis of the October, 1965, Coup in Indonesia (Ithaca: Cornell University, 1971).

12 For this relationship see Peter Dale Scott, The American Deep State: Wall Street, Big Oil, and the Threat to U.S. Democracy (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014 (pp.16-17, 22, 127-29.

13 Benedict R. Anderson, “Impunity and Reenactment: Reflections on the 1965 Massacre in Indonesia and its Legacy,” Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, April 15, 2013: “Army leaders, helped by advice and half-concealed support from both the Pentagon and the CIA – then reeling under heavy reverses in Vietnam – had long been looking for a justification for a mass destruction of the Party. Now the September 30th Movement and the murder of the six generals provided the opening they awaited.”

14 Bradley R. Simpson, Economists with Guns: Authoritarian Development and U.S.-Indonesian Relations, 1960-1968 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2008), p.173, 311n6.

15 Tim Weiner, Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA (New York: Doubleday, 2007), p. 260.

16 (1) Peter Dale Scott, Peranan C.I.A. Dalam Penggulingan Bung Karno. Buku ini dilatang beredar oleh KEJAGUNG RI. (West Berlin: Perhimpunan Indonesia, 1988);

(2) Peranan C.I.A. dalam penggulingan Bung Karno Konspirasi Soeharto-CIA : penggulingan Soekarno, 1965-1967 (Surabaya: Pergerakan Mahasiswa Islam Indonesia: Perkumpulan Kebangsaan Anti Diskriminasi, [1998]); (3) An anthology, Gestapu, matinya para jenderal dan peran CIA (Yogyakarta: Cermin, 1999); (4) Peter Dale Scott, CIA dan penggulingan Sukarno (Yogyakarta: Lembaga Analisis Informasi, 1999); (5) Peter Dale Scott, Amerika Serikat dan penggulingan Sukarno 1965-1967

([S.l. : s.n.], 2000); (6) Peter Dale Scott … et. al. ; editor, Joesoef Isak], 100 tahun Bung Karno : 6 Juni 1901-2001: sebuah liber(Jakarta : Hasta Mitra, 2001), pp. 278-316; (7) Peter Dale Scott, Peran CIA dalam penggulingan Sukarno (Jakarta: Buku Kita, 2007.

17 Jonathon Green, Encyclopedia of Censorship [New York: Facts on File, 2005], p. 278.

18 Zoe Reynolds, “Putu Oka Sukanta and Poetry from Prison,” Jakarta Post, July 25, 2013: “Others, such as Peter Dale Scott, a former Canadian diplomat and a professor at the University of California, claim that a dalang (or puppet master) — maybe the CIA, maybe Soeharto — was manipulating the events that led to … the bloodletting to come.” This breaking of journalistic silence in Indonesia was the more remarkable, in that an army general was still president.

19 Peter Dale Scott, “How I Came to Jakarta,” Agni, No. 31/32 (1990), p. 297.

20 R. Tanter, “The Totalitarian Ambition: Intelligence Organisations in the Indonesian State,” in State and Civil Society in Indonesia, ed. A.K. Budiman, (Monash: Centre of Southeast Asian Studies, 1990), 218: Jusuf Wanandi, Shades of Grey: A Political Memoir of Modern Indonesia, 1965-1998 (Jakarta: Equinox, 2012), p. 68.

21 In similar CIA-backed plots against Allende in Chile (1970-73), a loyalist Army Chief of Staff was also murdered, making way for a right-wing General Pinochet who would subsequently carry out an army coup and massacre. But these were two plots separated in time, not a single piggy-backed plot.

22 Paul Lashmar and James Oliver, “How We Destroyed Sukarno,” Independent (London), December 1, 1998,

23 Stephen Dorril, MI6: Inside the Covert World of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service (New York: Free Press, 2000), 718: “In co-operation with their colleagues from the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS), MI6’s Special Political Action group launched up to six different disruptive actions, including… the recruitment of ‘moderate’ elements within the army.”

24 John Roosa, review of Wanandi, Shades of Grey, Inside Indonesia.

25 Cf. Fact No. 5 above.