Spain Blocks Argentinian Attempts to Prosecute Franco-Era Fascists

Argentinian judge María Romilda Servini de Cubría has issued arrest warrants for four former Spanish fascists from the regime of dictator General Francisco Franco.

Spain’s ruling Popular Party (PP), which has its origins in Franco’s National Movement, and the opposition Socialist Workers Party (PSOE) have closed ranks to block the arrests.

They have cited the 1977 Amnesty Law, passed during the transition from fascism to bourgeois democracy following Franco’s death in 1975. Its aim was to prevent any reckoning and investigation into the crimes committed during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and Franco’s rule afterwards (1939-1975). Since then, not a single fascist has been brought to justice for crimes including an estimated 300,000 political opponents murdered, 500,000 imprisoned and 500,000 forced into exile.

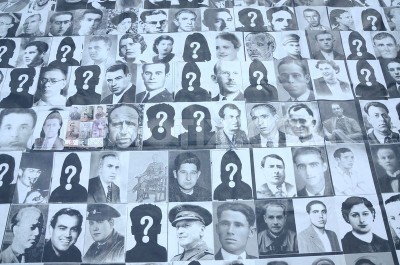

The case began in April 2010 after Argentinian resident Darío Rivas, son of an elected mayor of a Galician town in northwest Spain who was kidnapped and executed under Franco, made recourse to international law under which crimes against humanity have no limitations or jurisdictional boundaries. The trial now includes 120 individual plaintiffs and 62 human rights organisations.

Judge Servini wrote a 204-page report indicting four fascists, who were members of Franco’s political police, the Brigada Político Social, for crimes they committed.

Two of the accused, police commissioners Celso Galván Abascal and José Ignacio Giralte, died before the case began. The other two are police officers, Jesus Muñecas Aguilar, who also participated in the February 23, 1981, coup against the post-Franco state, and José Antonio González Pacheco, one of the most sadistic of Franco’s henchmen. He was known as “Billy the Kid” for his habit of spinning a gun around his finger while he beat his victims.

Direct evidence of Pacheco’s crimes has been given by Pérez Alegre, a former member of the Revolutionary Antifascist Patriotic Front (FRAP), who explained to El País, “They arrested me in October 1975. They took me to the DGS [Dirección General de Seguridad, the Francoist organ responsible for political repression], surrounded me and started beating me from all sides. There were five policemen. Billy the Kid hit me occasionally, but mostly he told the others what to do. They tied me to a radiator and hit me with truncheons on the back of my knees and in the kidneys…. When I had to go to the bathroom two people had to carry me there, since I couldn’t walk. I looked in the mirror and didn’t recognise my own body, which was deformed by the blows.”

Servini issued the arrest and extradition warrants for the four fascists to Interpol, declaring that under universal jurisdiction they could be charged under international law. She rejected attempts by the Spanish attorney general’s office to prevent the prosecution.

In their attempt to block the prosecution, the attorney general’s office, the PP government, and various judges and prosecutors have falsely claimed that there are “numerous judicial procedures open” in Spain that are investigating the Francoist crimes, and thus universal jurisdiction procedures are not valid. They also declared that Pacheco and Muñecas are immune from prosecution because they are protected by the 1977 Amnesty Law, which pardoned “possible crimes” committed by members of the security forces.

Nearly one month after Servini made her request to Interpol, which usually carries out such requests within hours, the two Francoist criminals remain free.

In a separate case, the United Nations Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances (OHCHR) instructed Madrid to “take on its responsibility” and draw up “a national plan to search for the missing,” revoke the 1977 Amnesty Law and bring cases of forced disappearance before the courts.

The OHCHR also criticised the “resistance” of Spanish authorities to declassifying documents from the Franco era, for obstructing the families of victims who wanted to access information and the Historical Memory Law passed by the previous PSOE government, for being “limited”.

At the time of the law’s passing in 2006, the World Socialist Web Siteexplained its purpose was “to divert this striving for the truth into safe channels for the Spanish ruling class. Not only does it continue the decades-long cover-up of the crimes of fascism, but it enshrines in law the claim that all sides in the civil war were equally guilty…. And, despite declaring the fascist sentences and executions unjust, the bill makes no firm commitment to overturn them in Spanish law or bring those responsible to justice.”

This warning was borne out in 2012 when National Court judge Baltasar Garzón was brought before the courts on charges that he abused his judicial power by launching an investigation into Francoist crimes. Garzón had demanded the regime be held accountable for murder, ordered mass graves to be opened and compensation paid to Franco’s victims, and began investigations into the disappearance of abducted babies.

Last May, Servini obtained the testimony of Garzón, who declared that there was no legal channel in Spain to investigate the crimes of Francoism after the Supreme Court prevented him from doing so. Questioned as to whether the attorney general’s office was investigating as claimed, he stated, “radically, no.… This court is the final judicial stronghold which remains for the victims of Franco to be repaired.”

The fact that the heirs of Francoism, the PP, can block any investigation of the crimes committed is due to the historical betrayal of the working class by the Stalinist Communist Party (PCE) and the PSOE during the transition.

Nothing exposed this more than Justice Minister Alberto Ruiz-Gallardón’s defence in parliament of the law by quoting PCE leaders such as Santiago Carrillo and Dolores Ibárruri (“La Pasionaria”), whom he declared, “Voted and were staunch defenders of the Amnesty Law”.

Gallardón’s father-in-law José Utrera Molina is one of the nine former government officials under Franco’s regime being investigated by Servini.

The PSOE and the PCE-led United Left (IU) are perpetuating the fraud that the Spanish authorities will address Franco’s crimes, while attempting to present themselves as defenders of his victims. In parliament, they are again urging the PP administration to locate and open all of the mass graves. Despite the Historical Memory Law, only 400 have been opened from which the remains of nearly 6,000 people who were shot have been exhumed of the approximately 114,000 who remain unaccounted for.

The PSOE has made clear that it defends the Amnesty Law. Ramón Jáuregui, a former minister under the Zapatero administration (2004-2011), stated, “It was a necessary law and we don’t think it is a good idea to annul it.”

Questioned about the Argentinian probe, Jáuregi replied, “The Argentinian initiative is full of good intentions, but in Spain we decided long ago that we weren’t going to look into what we did before 1976.”

The IU’s former leader, Gaspar Llamazares, has stated that there is no need to eliminate the law: “It would be enough to modify it to make sure that it cannot be interpreted as offering impunity to those who committed crimes under Franco.”

The ruling class and its parties are once again closing ranks to prevent any reckoning with Francoism. Under conditions in which 26 percent of workers are unemployed and 3 million Spaniards are in severe poverty, the same conditions that led to the revolutionary conditions of the 1930s are being created. Any investigation would undermine and provoke resistance to a ruling elite that is imposing austerity measures and social counterrevolutionary policies.