Selling Empire: American Propaganda and War in the Philippines

by Susan Brewer

And of all our race He has marked the American people as his chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world. This is the divine mission of America, and it holds for us all the profit, all the glory, all the happiness possible to man. Senator Albert J. Beveridge, 1900

I thought it would be a great thing to give a whole lot of freedom to the Filipinos, but I guess now it’s better to let them give it to themselves. Mark Twain, 1900

At the turn of the twentieth century, Americans and Filipinos fought bitterly for control of the Philippine Islands. The United States viewed the Pacific islands as a stepping-stone to the markets and natural resources of Asia. The Philippines, which had belonged to Spain for three hundred years, wanted independence, not another imperial ruler. For the Americans, the acquisition of a colony thousands of miles from its shores required a break with their anti-imperial traditions. To justify such a break, the administration of William McKinley proclaimed that its policies benefited both Americans and Filipinos by advancing freedom, Christian benevolence, and prosperity. Most of the Congress, the press, and the public rallied to the flag, embracing the war as a patriotic adventure and civilizing mission. Dissent, however, flourished among a minority called anti-imperialists. Setting precedents for all wartime presidents who would follow, McKinley enhanced the power of the chief executive to build a public consensus in support of an expansionist foreign policy.1

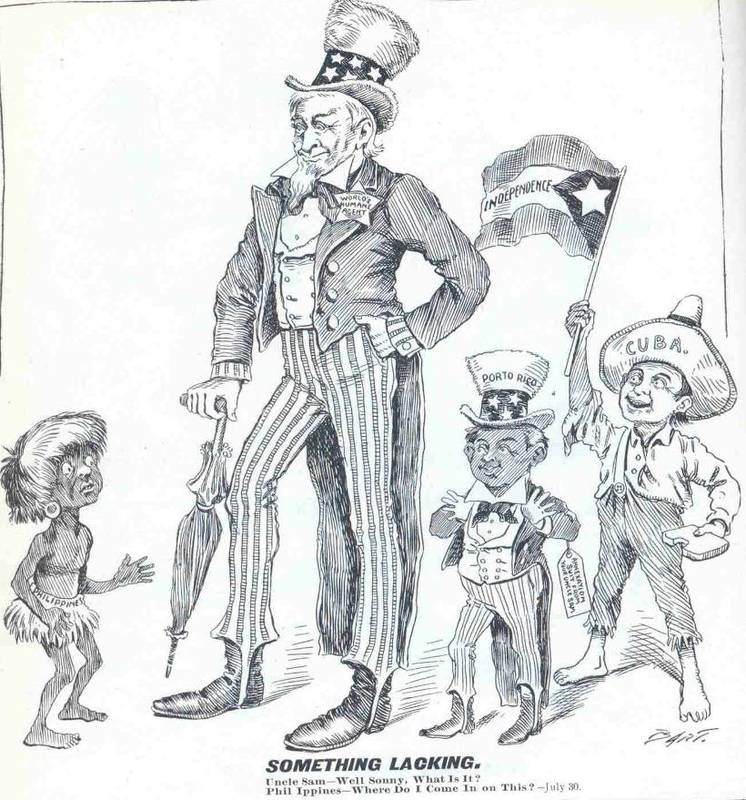

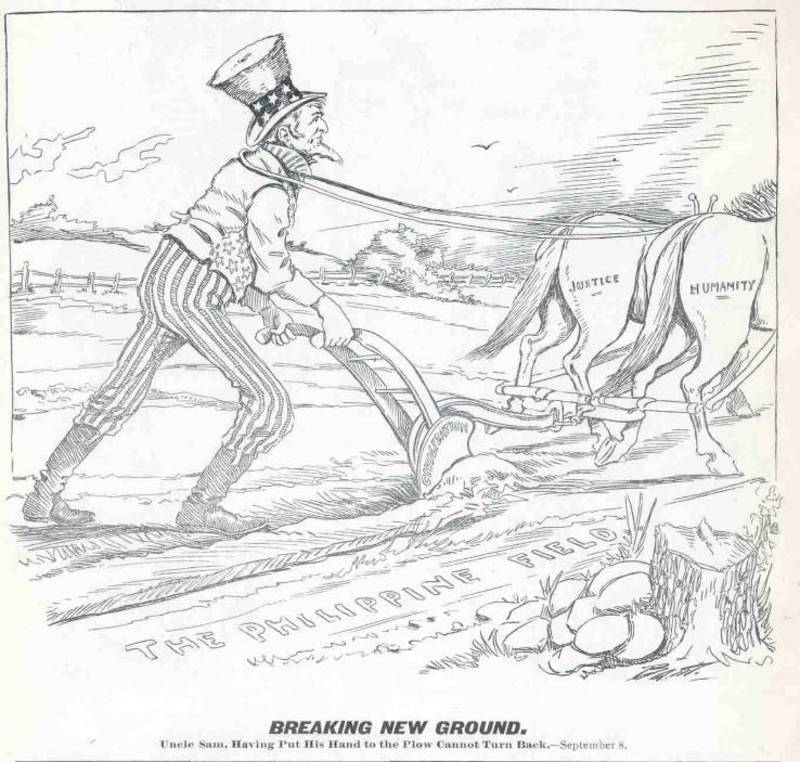

This article explores McKinley’s use of wartime propaganda extolling national progress and unity to aid his successful navigation of the transition of the United States to great power status. The president and his supporters did not portray the United States as an imperial power in the European manner. To win support for far-reaching changes in foreign policy, McKinley explained overseas expansion in terms of American traditions and drew on familiar themes from the past. The last Civil War veteran to serve as president, he celebrated the coming together of the North and South to fight a common enemy. He portrayed American expansion in the Pacific as a continuation of manifest destiny. He compared the Filipinos to Native Americans, calling them savage warriors or “little brown brothers.” Appealing to popular attitudes of the times, he encouraged Americans to fulfill their manly duty to spread Christian civilization. The United States, he asserted, was a liberator, not a conqueror.2

To rally support for his policy, the McKinley administration mastered the latest communication technology to shape the portrayal of the war by the media of the day. McKinley was the first to have his inauguration filmed and to have a secretary who met daily with the press, “for a kind of family talk,” as journalist Ida Tarbell put it. Reporters were provided with a table and chairs in the outer-reception room of the Executive Mansion where they could chat with important visitors and even the president if he approached them first. McKinley paid special attention to the representatives of the wire services, the news agencies that sent syndicated stories by telegraph to subscribing newspapers across the country. The president’s staff, which grew from six to eighty, monitored public opinion by studying daily hundreds of newspapers from around the country. To make sure that reporters accurately conveyed the president’s views, his staff issued press releases, timing the distribution so that reporters on deadline filed only the administration’s version of the story. Through news management, the McKinley administration disseminated war propaganda based on facts, lies, ideas, patriotic symbols, and emotional appeals.3

In contrast to the more rambunctious expansionists of the day, the genial McKinley exuded calm and dignity. As noted by his contemporary, the British historian and diplomat James Bryce, American leaders put considerable effort into leading opinion while appearing to follow it. The president spoke publicly of America’s expanded influence in the Caribbean and the Pacific as though it had happened by chance or been willed by God. His actions, however, made the acquisition of an empire no accident. In addition, his public position of passivity made it difficult for critics to challenge his policies until they were well under way. McKinley, observed the astute Henry Adams, a grandson and great-grandson of presidents, was “a marvelous manager of men.” While politicians, members of the press, and military men freely expressed their criticisms of U.S. policy, the president and his fellow expansionists took the country to war with Spain, built a consensus for keeping the Philippines, and maintained support for waging war against Filipinos who fought for their independence. In doing so, they constructed a persuasive version of U.S. policy in the Philippines as a “divine mission” that not only disguised the realities of war and conquest, but also would serve in years to come as an example of America’s commitment to spreading freedom.4

Competition for Empire

The war between the Americans and the Filipinos was just one of many colonial wars taking place in the late 1800s and early 1900s as the world’s industrialized powers scrambled for dominance in Africa and Asia. Britain doubled its imperial territory, France acquired three and a half million square miles including Indochina, and Russia expanded east. The aging Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, and Spanish empires struggled to hang on to what they had. Up-and-coming nations—Germany, Japan, and the United States—sought to expand their influence. Imperial powers clashed over faraway frontiers and subdued native peoples who resisted foreign rule. New technologies often made these fights one-sided. To fuel economic expansion, businessmen and traders competed over investments, raw materials, and markets, backing railroad construction in China, digging copper mines in Africa, and selling sewing machines to Pacific Islanders. Missionaries of many faiths crusaded for the souls of the “heathen,” preaching ancient beliefs as well as western attitudes about culture and consumer goods. Explorers raced to plant their flags. Claims of national glory accompanied many of these exploits, along with justifications of spreading progress and stability. Such fierce competition for territory, economic gain, and souls often produced upheaval instead.5

His goal, McKinley told Governor Robert LaFollette of Wisconsin was to “attain U.S. supremacy in world markets.” The United States had settled its western frontier, wrapping up thirty years of conflict with the Native Americans. With their own continental empire to manage, American expansionists seemed more interested in indirect imperialism—informal dominance through economic power—than direct imperialism, which entailed hands-on governance. For instance, U.S. companies already had made fortunes out of bananas and minerals from Latin America. To further economic expansion, Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan of the U.S. Navy advocated the construction of a canal through Central America, the buildup of a strong navy to protect trade routes, and the acquisition of refueling bases in the Caribbean and the Pacific. Mahan’s ideas had powerful support from McKinley, Senator Henry Cabot Lodge (R-MA), Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, and other expansionists, called “jingoes.” In particular, the United States wanted access to China with its millions of potential customers. So did Japan, Britain, Germany, Russia, and France. The imperial powers threatened to divide up China as they had Africa. In January 1898, the U. S. Minister to China warned Washington, “partition would destroy our markets.” Within months the United States would be a Pacific power practicing direct imperialism in the Philippines to advance indirect imperialism in China.6

American expansionists of the white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant middle and upper classes were confident that they could lead at home and overseas. Citing Social Darwinism and scientific studies that demonstrated the superiority of the white race, they viewed white American men to be dominant by virtue of their evolved good character and civilized self-control. The men of decadent Spain, they thought, had gone soft. They considered non-white people to be no more than children, primitive and wild, in need of the guidance of a big brother or great white father. Women, viewed as weak and passive, also required protection. Such attitudes reassured these leaders of their natural supremacy at a time when millions of Catholic and Jewish immigrants arrived from Southern and Eastern Europe, the women’s suffrage movement agitated for the vote, African Americans challenged the “color line” drawn by segregationists in the South, and workers and farmers demanded radical reforms. These leading men preferred the status quo at home. War overseas provided an escape from “the menace and perils of socialism and agrarianism,” thought Henry Watterson, the editor of the Louisville Courier-Journal, just “as England has escaped them, by a policy of colonialism and conquest.” In a nation at war, the leaders believed, everyone would know and accept their place in society whether at the top or the bottom. Freedom was only for “people capable of self-restraint,” said Theodore Roosevelt, who ironically was seen as a bit of wild man himself.7

American expansionists drew on these beliefs and interests to justify war with Spain in the summer of 1898 and the fighting in the Philippines that followed. For most Americans, the conflict with Spain was about the liberation of Cuba. By 1896, Cuban rebels, who carried out ruthless economic warfare by destroying cane fields, sugar mills, and railroads, had taken charge of more than half the island. To prevent civilians from supporting the rebels, Spanish authorities forced Cubans out of their villages into guarded “reconcentration camps,” where 100,000 died of disease and starvation. As Cubans and Spaniards fought on, American investors in Cuban railroads and sugar plantations lost millions. At his inauguration in March 1897, President McKinley referred to the turbulence in Cuba and declared that the United States wanted “no wars of conquest.” What the United States did want in Cuba was stability and economic access. McKinley informed Spain that it should put an end to the revolt, institute reforms, stop the reconcentration policy, and respect the human rights of the Cubans. Madrid proposed reforms that satisfied no one. As the upheaval continued, McKinley stepped up the pressure by ordering the new battleship U.S.S. Maine to Havana to protect American lives and property.

Americans followed the story of the Cuban Revolution in their many newspapers. New Yorkers alone could choose among eight morning and seven evening papers. They could read the Republican or Democratic papers for news that shared their politics. Or they could turn to the independent and, at three cents a paper, high-priced New York Times. For the less highbrow readers, there were the sensational “yellow journals.” To increase circulation, publishers Joseph Pulitzer of the New York World and St. Louis Post Dispatch and William Randolph Hearst of the New York Journal and San Francisco Examiner competed for readers (and advertisers) with exposés, stunts, comics, sports coverage, women’s features, and exciting accounts of foreign conflicts. They believed that war, especially the way they reported it, sold papers. Some histories have blamed yellow journalism for stirring up such frenzy for war with Spain that McKinley was compelled to undertake one. Although McKinley’s actions do not support this view, the stories featured in the yellow press did shape popular perceptions of the conflict. In contrast to the anti-war papers, with their accounts of complicated political problems and atrocities committed by both sides, the high circulation yellow press filled their pages with one-sided stories of Spain’s crimes of mutilation, rape, and murder.8

When the Maine blew up in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898, Americans were stunned by the loss of 266 sailors and outraged at the destruction of their ship. The administration asked for calm, appointed an expert board of inquiry to investigate the explosion, and accepted Madrid’s expressions of sympathy. Speaking at the University of Pennsylvania, McKinley said Washington would rely on God for guidance. Privately, he told Senator Charles W. Fairbanks (R-IN) that the administration would “not be plunged into war until it is ready for it.”9 The jingoes, meanwhile, were bursting with anticipation for war. Luck was with them when the official inquiry, without consulting the navy’s ordnance expert or chief engineer, concluded that an external explosion caused by a mine had destroyed the Maine, a verdict that was widely interpreted to mean that Spain was culpable even though the report did not say so. In a later investigation, the U.S. Navy determined that an internal explosion involving the fueling system most likely had destroyed the ship. At the time, however, McKinley fed the widespread impression of Spain’s guilt by saying that anything that happened in Havana was ultimately its responsibility.

McKinley prepared for war by calling for a military buildup. Congress appropriated fifty million dollars, three-fifths of which went to the Navy. The rest went to the Army, which assumed that only small forces would be needed to take beaches and aid the Cubans and so used most of its appropriation on coastal fortifications. In late February, without permission, the gung-ho Assistant Secretary Roosevelt put naval units on alert. Although all attention was on the Caribbean, he did not ignore Spain’s colony in the Philippines. He ordered George Dewey, the commander of the Asiatic Squadron, who had been busy searching the coast of China for the best site for an American port, to proceed to Hong Kong and stand at the ready. Secretary of the Navy John Long and the president countermanded most of Roosevelt’s orders, but not the one to Dewey. As for Spain, it had 150,000 troops in Cuba exhausted by fighting and disease, 20,000 in the Philippines, and an antique navy. Well aware that a single U.S. battleship could take out one of their entire squadrons, Spanish officers steeled themselves for what they hoped would be an honorable defeat.10

As the Spanish government searched for a compromise solution, the European powers considered whether they should take sides. From the Vatican, the pope asked McKinley to avoid a war by accepting Spain’s promise of an armistice with the rebels. Germany, which had its eye on Spanish possessions in the Pacific, and France proposed mediation. McKinley politely rejected these offers. The British decided to support the Americans by doing nothing. The president received reports that American business leaders had concluded a war might enhance opportunities for trade, investments, and profits. Congressional support consolidated after Senator Redfield Proctor (R-VT) returned from Cuba with a vivid description of the suffering under Spanish rule. His colleague from Wyoming, Senator Francis E. Warren, expressed growing indignation, “that we, a civilized people, an enlightened nation, a great republic, born in a revolt against tyranny, should permit such a state of things within less than a hundred miles of our shore as that which exists in Cuba.”11

Once ready to wage war, McKinley explained his reasons to Congress on April 11, 1898. By custom, he did not deliver his message in person, but sent it to be read out loud to the legislators by clerks. The president defined U.S. aims as ending the war between Spain and Cuba, establishing a stable government in Cuba, and insuring peace and security for both the citizens of Cuba and the United States. After calling for the use of force to achieve these purposes, the president mentioned in passing that Spain had proclaimed a suspension of hostilities in Cuba. In other words, Spain had made one more major concession. He closed by asking Congress to consider this development as it pondered action true to “our aspirations as a Christian, peace-loving people.” The Philippine Islands were never mentioned.

As Congress prepared to declare war on Spain, the big debate was not over whether to go to war, but whether the United States should recognize the revolutionary government in Cuba. The debate illustrated the gap between the public’s and the administration’s perceptions of what the war was about. McKinley’s aim was American access to a stable Cuba, not Cuban independence. As historian Louis Pérez has pointed out, the Cuban rebels were on the verge of achieving independence on their own. If they did, they might decide to pursue freedom from foreign domination not only by kicking out Spain, but also the United States. McKinley persuaded the lawmakers not to recognize Cuban independence. The United States and Spain declared war on each other at the end of April.12

As much as he could, McKinley centralized war news in the Executive Mansion. In the war room, he installed twenty telegraph wires and fifteen phone wires with direct connections to the executive departments and Congress. From the Executive Mansion, it took a speedy twenty minutes for a message to reach army headquarters in Cuba. To protect the secrecy of troop movements, McKinley ordered military censorship in Florida and in New York City, home of the wire services. The press complained, but complied. On May 17, the Associated Press (AP) resolved “to loyally sustain the general government in the conduct of the war” by avoiding publication of “any information likely to give aid to the enemy or embarrass the government.”13

To expand the regular army, McKinley called up 200,000 volunteers from National Guard units; each state was given a quota based on population. The commander-in-chief personally chose officers, considering party obligations, competence, and his theme of national unity. Most famously he gave commands to former Confederates, General “Fightin’ Joe” Wheeler and Fitzhugh Lee, nephew of General Robert E. Lee who had surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant in 1865. The troops’ lack of preparation was remarked upon by Kansas newspaper editor William Allen White. “The principal martial duty the National Guards had to perform before they were mustered out,” noted White, “was to precede the fire company and follow the Grand Army squad in the processions on Memorial Day and the Fourth of July.” White was confident that American citizen soldiers, as clumsy as they were, soon would be transformed into a disciplined regiment, a “human engine of death.”14

On the first of May, George Dewey sailed his fleet from Hong Kong to the Philippines and into Manila Bay. He gave the order “You may fire when ready, Gridley,” and oversaw the efficient destruction of Spain’s Pacific naval force without losing a single American sailor. Ships from the British, French, and German navies witnessed his triumph. As Dewey’s fleet attacked, a British naval band showed their support by playing “The Star Spangled Banner,” a song whose lyrics had been composed by an American as the British bombarded Baltimore in the War of 1812. The Germans, with their five warships in Manila Bay, proved more troublesome as time went on, making clear their interest in any available islands. The British for their part much preferred the United States as a partner in the Pacific to Germany. To control information from his end, Dewey cut the transoceanic cable, which meant that news of his victory was transmitted through Hong Kong and reached the United States on May 7. The dramatic reports of Joseph L. Stickney of the New York Herald, who blurred the line between reporter and participant by serving as Dewey’s aide during the battle, Edward W. Harden of the New York World and the Chicago Tribune, and John McCutcheon, cartoonist of the Chicago Record made Dewey a national hero. Quick to capitalize on the victory, entrepreneurs slapped Dewey’s picture or name on songs, dishes, shaving mugs, baby rattles, neckties, and chewing gum.15

McKinley adopted a public face of reluctance and uncertainty about the Philippines while he moved to take control. He remarked that “old Dewey” would have saved him a lot of trouble if he had sailed away once he defeated the Spanish fleet. Although certainly true, McKinley followed up Dewey’s victory by sending 20,000 troops under General Wesley Merritt to the islands. The president decided, “While we are conducting war and until its conclusion, we must keep all we get. When the war is over we must keep what we want.” He told committed expansionist Henry Cabot Lodge that he had doubts about keeping all of the islands, but “we are to keep Manila.” The president continued, “If, however, as we go on it is made to appear desirable that we should retain all, then we will certainly do it.” Over the next several months, Senator Lodge and his fellow jingoes dedicated themselves to make it “appear desirable.” As for American troops, they were shipped overseas on an open-ended mission with inadequate intelligence. Caught by surprise, the War Department could provide Merritt’s staff with only an encyclopedia article on the Philippines. Even so, Lt. Col. Edward C. Little of the 20th Kansas Volunteer Infantry Regiment, had a good idea of their objective. He told his men, “We go to the far away islands of the Pacific to plant the Stars and Stripes on the ramparts where long enough has waved the cruel and merciless banner of Spain.”16

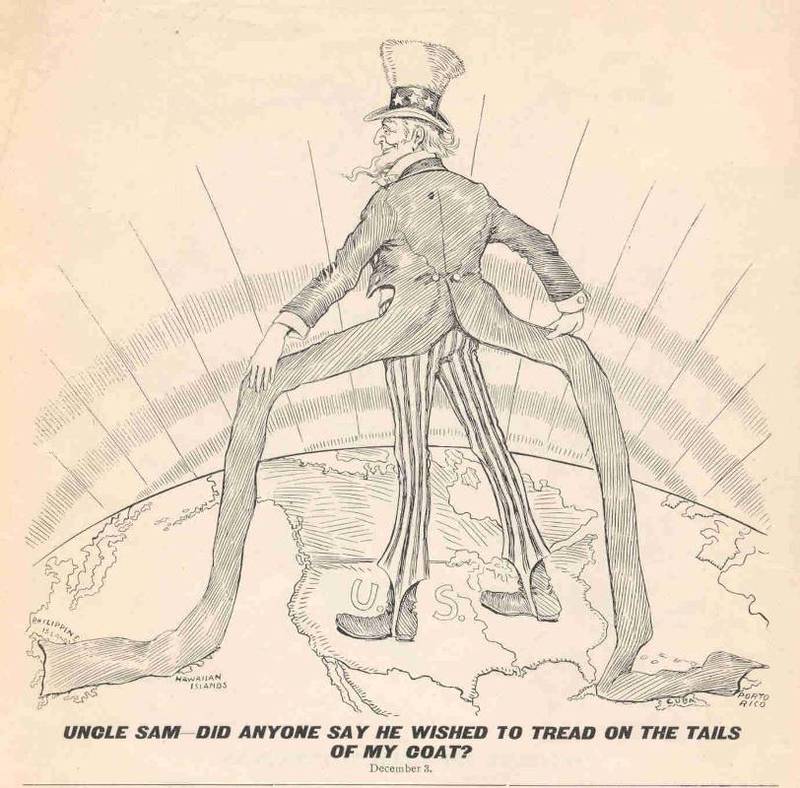

On their way to the Philippines, U. S. forces stopped to take the island of Guam from Spanish officers who didn’t know they were at war. At the same time, McKinley stepped up plans to acquire the Hawaiian Islands. The president told his secretary, “We need Hawaii just as much and a good deal more than we did California. It is manifest destiny.”17 Five years earlier, U.S. marines and warships had provided support for the overthrow of Queen Lili’uokalani led by pro-American plantation owners. Urging annexation during the war with Spain, Senator Lodge made the case that if the United States didn’t take the islands now someone else would, an argument that he would use again regarding the Philippines. Congress made Hawaii a U.S. territory by joint resolution despite petitions of protest from Hawaiians. With the islands of Hawaii, Guam, and the Philippines, the United States would have the refueling bases for naval and merchant ships in the Pacific so desired by expansionists. The U.S. defeat of Spanish forces in Cuba in mid-July enhanced U.S. dominance over the Caribbean.

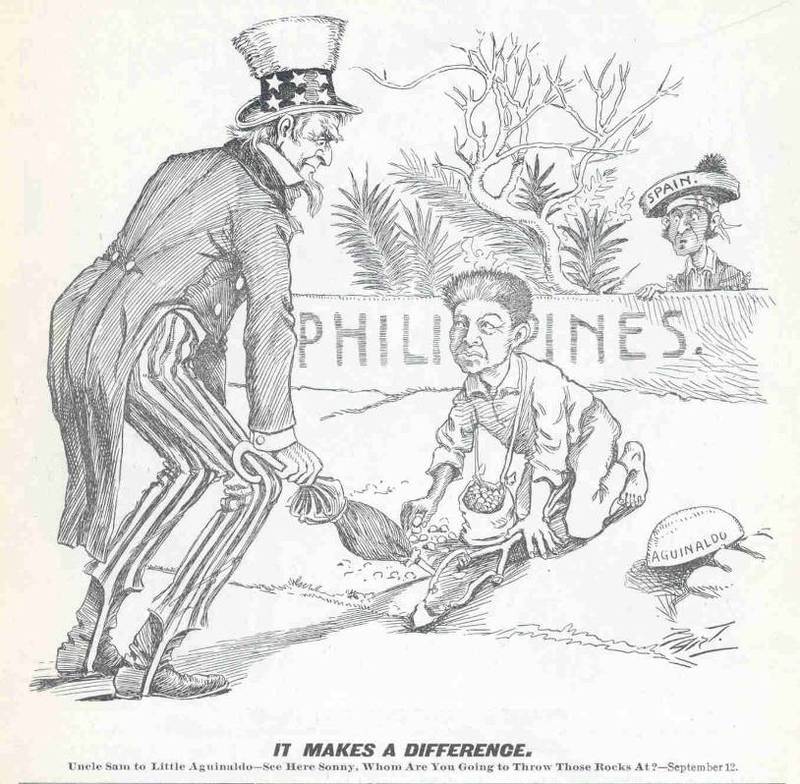

In the Philippines, the big problem for the U. S. military was not Spain, but the army of Filipinos headed by the twenty-seven year old Emilio Aguinaldo. Spanish colonial administrators had faced a growing nationalist movement led in 1897 by Aguinaldo who declared the Philippines independent, named himself president, and called for rebellion. When Spain began to use the same repressive tactics it used in Cuba, Aguinaldo accepted a truce, which included his exile to Hong Kong. He remained there until Dewey had him returned to the Philippines to help the Americans in their fight against Spain. In short order, Aguinaldo resurrected an army, took control of all of the islands with the exception of Manila, a few ports, and the areas inhabited by Muslims, issued a declaration of independence, and set up an elite-dominated government with a national assembly of lawyers, doctors, educators, and writers. Then U. S. army troops arrived, carrying instructions that they were not to share authority in the islands with the Filipinos. General Thomas M. Anderson sent Aguinaldo a message: “General Anderson wishes you to inform your people that we are here for their good and that they must supply us with labor and material at the current market prices.”18

Recognizing the Filipino people as the real threat, the American command worked out a deal with the Spaniards to stage a mock battle of Manila on August 13, 1898. They would shoot at each other and then Spain would surrender before the Philippine Army of Liberation could take part. As the Americans raised their flag over Manila, the outraged Filipinos cut off the city’s water supply. General Merritt was forced to negotiate and allow Filipinos access to their capital city. Merritt sailed for the Spanish-American peace conference held in Paris, leaving General Elwell S. Otis, a graduate of Harvard Law School and a veteran of Gettysburg and the Indian wars, in command. Relations between the Filipinos and the Americans were both tense and friendly. Manila was an “odd place,” wrote volunteer Wheeler Martin to his family in Idaho. “They cant talk english nor we can’t understand them,” but there lived “some of the prettyest women I ever saw in my life.” A number of U.S. soldiers, who referred to the Filipinos as “niggers” and “gugus,” expected deference from the “natives.” Filipinos, who knew something about the tragic history of Native Americans and African Americans, expressed their belief that it might be better to die fighting than live under U.S. control.19

Its victory over Spain meant that the United States had become a world power. “Our army’s greatest invasion of a foreign land was completely successful,” war correspondent Richard Harding Davis wryly concluded, “because the Lord looks after his own.” Other commentators were from “the Lord helps those who help themselves” school of analysis. McClure’s Magazine ran an article replete with statistics and charts showing that the United States had become so strong it could prevail in war against any combination of European nations. Blue and gray had fought together, celebrated McKinley. Theodore Roosevelt trumpeted the uniting in battle of the economic and social classes so divided by industrial strife between business and labor. The fashion magazine Vogue wasn’t so sure that class unity was a positive development. It expressed regret that “our democracy” required gentlemen to mingle with the other classes in military units, fearing that “constant contact with the rougher element … would affect a man’s character.” Spain, which had been so vilified in the weeks leading up to war, was now seen as gallant in defeat. The peoples of Cuba and the Philippines who the Americans had pledged to liberate began to be portrayed by the administration and the press as child-like, violent, incompetent, and untrustworthy.20

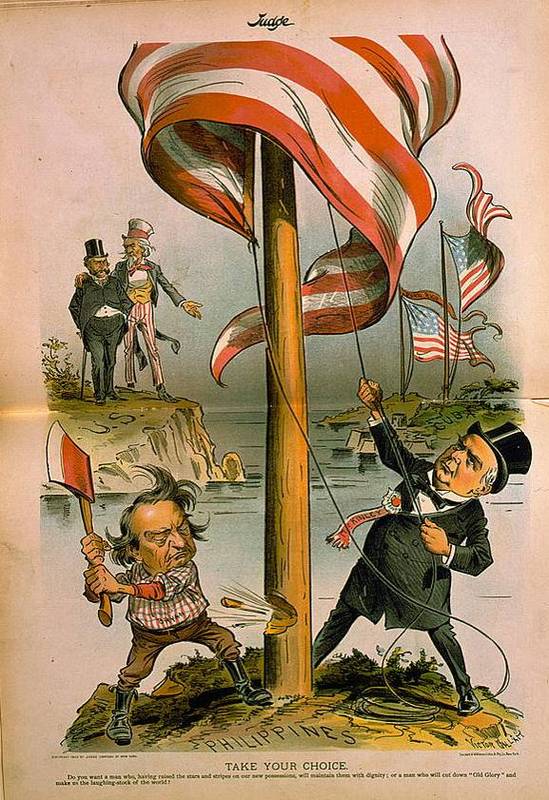

Campaign to Keep the Philippines

As the peace talks with Spain began in the fall of 1898, McKinley announced that he would make a speaking tour to “sound out” opinion on what to do with the Philippines. His real purpose was to build support for keeping them. In fifty-seven appearances, McKinley linked patriotism with holding the islands. At train stops, he frequently commented with pleasure on seeing children waving “the glorious old banner of the free.” He also sought approval to keep troops in the Pacific, even though, as Democratic leaders pointed out, the men had enlisted to free Cuba. McKinley’s aides made sure that his appearances in mid-western towns reached a wide audience. They took along a train carload of reporters from the wire services, national magazines and big city newspapers. The president’s staff distributed advance copies of formal speeches along with numerous bulletins complete with human-interest anecdotes, which frequently appeared word for word as news stories. Newspaper editors got the message and reported that it looked like the United States would be keeping the Pacific islands.21

President McKinley greets the citizens of Alliance, Ohio, from the rear platform of his train, 1900. (Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-102871) President McKinley greets the citizens of Alliance, Ohio, from the rear platform of his train, 1900. (Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-102871) |

McKinley struck two major themes, unity and progress, as he spoke to cheering crowds in Iowa. To the people of Clinton, he said, “North and South have been united as never before. People who think alike in a country like ours must act together.” He suggested that where war and foreign policy were concerned politics should stop at the water’s edge. At Denison, he said, “Partisanship has been hushed, and the voice of patriotism alone is heard throughout the land.” In Chariton, he spoke of the peaceful acquisition of Hawaii in addition to the Spanish territories. “And, my fellow-citizens, wherever our flag floats, wherever we raise that standard of liberty, it is always for the sake of humanity and the advancement of civilization,” proclaimed McKinley. “Territory sometimes comes to us when we go to war for a holy cause, and whenever it does the banner of liberty will float over it and bring, I trust, blessings and benefits to all the people.” At Hastings, the president was direct about the rewards of war: “We have pretty much everything in this country to make it happy. We have good money, we have ample revenues, we have unquestioned national credit; but we want new markets, and as trade follows the flag, it looks very much as if we were going to have new markets.” To the people of Arcola, Illinois, the president spelled out what it meant to have foreign markets: “When you cannot sell your broom-corn in our own country, you are glad to send the surplus to some other country, and get their good money for your good broom-corn.” When McKinley returned to Washington, he remarked that “the people” seemed to expect that the United States would keep all of the Philippines.22

The administration had wanted Manila as a base and decided early on to hold the island of Luzon to protect the capital city. When the Navy argued that it would be better to have all of the islands, McKinley agreed. He accepted General F. V. Greene’s pro-expansion report on the commercial opportunities of the islands. Numerous articles and books about “our new possessions” outlined their potential for supplying Americans with coffee, sugar, and mineral wealth. Washington instructed U.S. authorities in the Philippines not to promise anything to “the natives” or to treat them as partners, but to avoid an outright conflict. For their part, Aguinaldo and his supporters, committed to the goal of independence, were divided on how best to proceed, unsure whether to ask for American protection of their independence or formal recognition. 23

McKinley organized the Peace Commission so that expansionists would dominate the delegation to Paris, carefully including prominent Senators since the Senate would have to ratify any treaty. During their deliberations, the commissioners were briefed by General Charles A. Whittier, who said that, based on his meetings with Aguinaldo, the Filipino leader would not be difficult to manage. Furthermore, he reassured them as to “the ease with which good soldiers could be made out of the natives, provided they were led by white officers.”24 With Spain, the commissioners negotiated a treaty which gave the United States control of Cuba, Puerto Rico, Guam, and for twenty million dollars, the Philippine Islands.

Shortly after the president signed the treaty, but before it was submitted to the Senate for ratification in late December 1898, he sent orders to General Otis in the Philippines announcing that “the mission of the United States is one of benevolent assimilation.” McKinley continued, “In the fulfillment of this high mission, supporting the temperate administration of affairs for the greatest good of the governed, there must be sedulously maintained the strong arm of authority, to repress disturbance and to overcome all obstacles to the bestowal of the blessings of good and stable government upon the people of the Philippine Islands under the free flag of the United States.” This elaborate message expressed the desired combination: a free United States and a stable Philippines. The War Department instructed Otis to “prosecute the occupation” with tact and kindness, avoiding confrontation with the insurgents by being “conciliatory but firm.” Aguinaldo, convinced that the Senate would reject the treaty because it so grievously violated American principles, maintained a siege of Manila. His envoy Felipe Agoncillo traveled to Paris where both sides at the peace talks ignored him. Agoncillo returned to Washington to make the case that the “greatest Republic of America” should recognize the first Republic of Asia or there would be conflict, but no official would see him.25

As McKinley’s plan to take the Philippines became clear, a number of Americans spoke out in opposition for a variety of reasons, some principled, some practical. Anti-imperialists included former presidents, the Democrat Grover Cleveland and the Republican Benjamin Harrison, industrialist Andrew Carnegie, labor leaders Samuel Gompers and Eugene V. Debs, philosopher William James, and writer William Dean Howells. Satirists Mark Twain and Peter Finley Dunne mocked the high-sounding rhetoric of humanitarianism and morality, which they saw as a cover for racism and greed. Dunne’s famous character, the barkeeper Mr. Dooley, said it was a case of hands across the sea and into someone’s pocket. African American leaders Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois believed that the Filipinos could govern themselves and certainly would do a better job than the United States judging by its record with non-white people at home. Other anti-imperialists were white supremacists who believed that any effort to prepare Filipinos for self-government would fail. Women’s rights groups, still fighting for the vote, sympathized with the Filipinos who faced the prospect of being governed without their consent. Those with strategic concerns pointed out that the United States always had depended on the Pacific Ocean as a barrier, protecting it from attack. Acquisition of hard-to-defend bases at Manila and Pearl Harbor would make the United States more vulnerable.26

Despite the organization of the Anti-Imperialist League with its 30,000 members, the Senate ratification of the peace treaty appeared likely. The economy was booming and the Republicans did well in the off-year elections. The president’s critics accused him of either being a genial hack, the tool of bosses and capitalists, or a mastermind, craftily forging an empire by trampling over the Constitution and Congress, a sure indication that they were demoralized and did not know how to challenge him. The president made another tour to promote his Philippines policy, this time through the South, where in Savannah he asked, “Can we leave these people, who, by the fortunes of war and our own acts, are helpless and without government, to chaos and anarchy, after we have destroyed the only government they have had?” He answered, “Having destroyed their government, it is the duty of the American people to provide for a better one.” The president dismissed as unpatriotic any suggestion that the American people were incapable of creating a new government for others. On February 6, 1899, the Senate ratified the treaty with one vote to spare, dividing largely along party lines, which meant that partisan politics may have had more to do with the outcome than the outbreak of fighting in the Philippines the day before.27

War in the Philippines

“Insurgent dead just as they fell,” 5 February 1899. (National Archives, III-AGA-3-22) “Insurgent dead just as they fell,” 5 February 1899. (National Archives, III-AGA-3-22) |

No one knows for sure who fired the first shot. The opening battle followed weeks during which both sides had engaged in provocations. Most accounts identify Americans from the 1st Nebraska Regiment as the ones who opened fire when three or four Filipinos failed to halt as ordered. But the story that first reached the Executive Mansion, courtesy of the New York Sun, reported that the insurgents had attacked. McKinley never wavered from this version, later elaborating on it by claiming that the attacking insurgents had violated a flag of truce and shot down U.S. soldiers while they treated wounded Filipinos. How the Filipinos came to be wounded went unexplained. The president was confident that the United States would easily and quickly pacify the islands. Reports of the first battle in which forty-four Americans and seven hundred Filipinos were killed helped to inspire such confidence. Washington called the conflict an insurrection; the Philippine Republic considered it a fight for independence.28

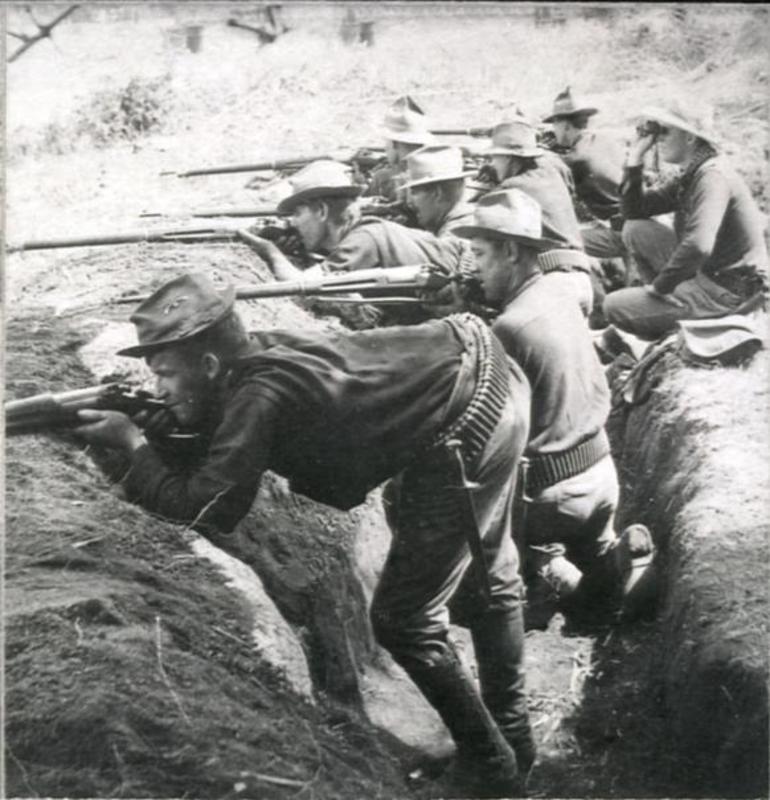

Between February and November 1899, Americans and Filipinos fought a conventional war with regular armies and set battles. The American forces maintained an average troop strength of 40,000, the Filipinos between 80,000 to 100,000 regulars. Military historian Brian McAllister Linn described the Filipino Army as intrepid and courageous with an impressive infantry, but suffering from inadequate training and lack of weapons and ammunition. The Americans had greater skills, effective and powerful weapons, and a navy that shut down coastal and island traffic. Late in the year, Filipino forces turned to guerrilla tactics designed to hit the Americans at their weak points. U.S. troops occasionally sighted and pursued the enemy, only to come upon farmers working hard in a field. Private Frederick Presher of New Jersey suspected they were “quick change artists,” but had no proof. Aguinaldo exercised less control over his forces in the guerrilla phase, and the fighting continued after he was captured in 1901. The Filipino strategy aimed to wear out the Americans and make their occupation too costly to continue.29

Emilio Aguinaldo (second seated man from right) and other insurgent leaders. (National Archives, 391-PI-34). Emilio Aguinaldo (second seated man from right) and other insurgent leaders. (National Archives, 391-PI-34). |

To carry out benevolent assimilation, the U.S. Army pursued a “carrot and stick” policy developed during the Civil War and Indian wars. It rewarded cooperation with reforms and punished opposition with coercion, destruction of property, and death. General Otis applied his significant administrative skills to civic action programs. McKinley established a Philippines Commission to visit the islands and determine what should be done to maintain “order, peace and the public welfare.” The commissioners reported that the Filipinos were not ready for independence. McKinley set up a second Commission, led by William Howard Taft, a fellow Republican from Ohio, to serve as the U.S. governing authority. The U.S. civilian and military authorities attempted to woo Filipino elites with promises of opportunity and privilege. General Arthur MacArthur ordered his soldiers to establish “friendly relations with the natives.”30 Otis, like McKinley, was confident of success because he mistakenly thought only a small percentage of Filipinos opposed American rule.

At home, millions of viewers saw the administration’s optimism about the war reflected in films. The new motion picture companies discovered that audiences were eager to watch dramatic scenes of their military forces in victorious action. The films, each less than a minute long, served as a “visual newspaper and as propaganda,” according to film historian Charles Musser. Some films featured actual footage of troops marching and ships sailing. Others were faked and called “reenactments.” For example, the box-office hit Battle of Manila Bay was made on top of a roof in New York City with cardboard ships floating in a table turned upside-down and filled with water. Thomas Edison’s company produced six reenactment films set in the Philippines and shot in New Jersey. In Advance of Kansas Volunteers at Caloocan, made in June 1899, white American soldiers wave the flag as they triumphantly defeat the Filipinos played by African Americans. Such films and others in which actors in blackface played Filipinos reinforced the perception that the war was about superior, white Americans subduing a dark and inferior enemy. Theater owners further enhanced the spectacle with the sound of gunfire or spreading smoke through the audience who would hiss at the enemy and cheer the raising of the American flag. Musser concludes that, during the war, the movie showmen “evoked powerful patriotic sentiments in their audiences, revealing the new medium’s ideological and propagandistic force.”31

Press reports from the Philippines indicated that victory might not be as imminent as the film reenactments or Otis’s official reports suggested. The military placed few restrictions on war correspondents, who traveled, ate, camped, and sometimes joined in combat operations with the troops. Reporters wrote that Otis “never visited the lines” and refused to heed the analysis of those at the front. In the popular magazine Collier’s Weekly, Frederick Palmer noted, “General Otis does not impart his plans to anybody either before or after they have failed.” One general told Palmer that he disagreed with Otis on strategy: “I want to lick the insurrectos first and reason with them afterward. He wants to reason with them and lick them at the same time.” In June 1899, correspondent John Bass, who reported for Harper’s Magazine, observed that the “whole population of the islands sympathizes with the insurgents” and that “the American outlook is blacker now than it has been since the beginning of the war.”32 Reporters, who for the most part endorsed expansionist policies, criticized what they saw as Otis’s ineffectiveness because they wanted the U.S. military to succeed.

Reporters also objected to what they saw as excessive censorship. The Army controlled the one telegraph line out of Manila and reviewed all press reports. Otis assured Washington that his censors allowed reporters to cable “established facts,” but not the “numerous baseless rumors circulated here tending to excite the outside world.” In the summer of 1899, the censor blocked a story reporting that General Henry Lawton thought it would take at least 75,000 troops to pacify the islands, a story that reinforced the impression that all was not going as well as Otis claimed. When correspondents objected, Otis threatened to expel or court-marital anyone who sent a formal letter of complaint from Manila. The frustrated reporters transmitted their complaint to the United States via Hong Kong and charged that censors clamped down on news not because it would harm operations but because it would upset people back home. They accused Otis of attempting to make things look better than they were by fixing casualty reports, overrating military accomplishments, and underestimating the Filipinos’ commitment to independence. The administration was implicated in these charges because it released Otis’s official reports, making it hard to tell, as the Cleveland Plain Dealer pointed out, “whether Otis misled the administration or the administration misled the public on its own.” Even the expansionist press joined in the criticism, except the McKinley loyalists who argued that only the president could be in the position to know what news of the war was safe to report. The president announced that he would continue to support Otis’s censorship policies.33

Although soldiers and reporters tended to believe that Filipinos were inferior to Americans, some learned to respect their opponents’ tenacity. For example, Colonel Frederick Funston told a correspondent that the enemy was “an illiterate, semi-savage people, who are waging war, not against tyranny, but against Anglo-Saxon order and decency.” Palmer’s reporting, however, gave the Filipinos credit for effective fighting. “But the island of Luzon is large,” he wrote, “and the Lawton expedition, such is the excellence of Aguinaldo’s intelligence bureau, was not more than fairly started before the Filipino army appeared on the flank of MacArthur’s division opposite to where it was wanted and began taking pot shots at the worn and cynical Montana regiment.”34

“Our Boys entrenched against the Filipinos,”1900. (National Archives, 165-F5-16-13634) “Our Boys entrenched against the Filipinos,”1900. (National Archives, 165-F5-16-13634) |

William Oliver Trafton, a 22-year-old Texas cowhand who enlisted for adventure, referred to the enemy as savages, wild varmints, and Indians. When he endured more hardship than adventure, he developed some admiration for the Filipinos. Before a battle Trafton talked with his friend:

He says, “Hell, they sure won’t kill only 40 of us.”

I says, “You told me that we could whip the whole thing in two weeks.”

He says, “Haven’t we licked them every time that we have had a fight?”

I says, “Yes, but the damn fools won’t stay whipped.”35

Like many Americans, Trafton had underestimated the Filipinos’ determination to resist.

The Debate over Empire

The resistance of the Filipinos to U.S. rule required some adjustment in the administration’s presentation of its policy. McKinley still portrayed the American cause as humanitarian, expressing his sorrow that certain “foolish” Filipinos had failed to recognize the benefits of American generosity. A year after the sinking of the Maine, McKinley stood in the Mechanics’ Hall in Boston, the capital of the anti-imperialist movement, before portraits of Washington, Lincoln, and himself labeled “Liberators,” to explain to an audience of almost six thousand that the United States sought to emancipate the Philippines.“No imperial designs lurk in the American mind,” he asserted. Dismissing controversy, McKinley said it was not “a good time for the liberator to submit important questions concerning liberty and government to the liberated while they are engaged in shooting down their rescuers.” Ironically, the news that the Filipinos were fighting for their independence was used to justify the argument that they weren’t ready for it. With exasperation, the anti-imperialist Nation commented, “McKinley is one of the rare public speakers who are able to talk humbug in such a way as to make their average hearers think it excellent sense, and exactly their idea.”36

As opposition to the war grew at home, McKinley linked support for the troops with support for his policies. The president spoke at the August homecoming of the Tenth Pennsylvania Regiment in Pittsburgh. He expressed his confidence in General Otis, his praise for the troops who served their country “in its extremity,” and his disdain for critics who said the soldiers should be brought home. He argued that without U.S. soldiers, the Philippines would be in chaos and suffering under the rule of “one man, and not with the consent of the governed.” Here he somehow implied that the Filipinos themselves prevented the establishment of “the consent of the governed,” but in the same speech he stated that the goal was the creation of a government there under the “undisputed sovereignty” of the United States. The most dramatic moment of the ceremony came when McKinley slowly read a list of the regiments engaged in the Philippines: “First California, First Colorado, First Idaho, Fifty-first Iowa, Twentieth Kansas, Thirteenth Minnesota, First Montana, First Nebraska, First North Dakota, Second Oregon, Tenth Pennsylvania, First South Dakota, First Tennessee, Utah Artillery ….” As he did, the soldiers of Pennsylvania roared their appreciation for each regiment. By celebrating unity with a roll call of the states, the president, with the help of cheering soldiers, could drown out dissent.37

President McKinley reviews the state militia in Los Angeles, 1901. (Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-122820). President McKinley reviews the state militia in Los Angeles, 1901. (Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-122820). |

McKinley and his fellow expansionists linked national glory to power and economic interests. Just before he left on another autumn tour to promote his policies, the president privately told his secretary, George Cortelyou, “one of the best things we ever did was to insist upon taking the Philippines and not a coaling station or an island, for if we had done the latter we would have been the laughing stock of the world. And so it has come to pass that in a few short months we have become a world power.” The president, who tended to be less specific about American power in public, left the more assertive statements to his supporters. In Collier’s Weekly, Lodge made the persuasive case that if left alone, the Philippines would be vulnerable to takeover by some European power not bothered by issues of self-government. He described the islands as rich in natural resources and a large potential market “as the wants of the [Filipinos] expand in the sunshine of prosperity, freedom and civilization.” Moreover, the islands provided access to even greater markets in China. “Will the American people reject this opportunity?” Lodge asked. “Will they throw away all this trade, and all this wealth?” He didn’t think so.38

The expansionists mustered racial arguments to justify U.S. policies. Senator Albert J. Beveridge told the Senate that race was more powerful than the Constitution. “God has not been preparing the English-speaking and Teutonic peoples for a thousand years for nothing but vain and idle self-contemplation and self-admiration. No!” he declared. “He has made us the master organizers of the world to establish system where chaos reigns.”39 Without U.S. control, Lodge predicted “bloody anarchy” among the eight million people of many different races and tribes speaking fifty or sixty languages and dialects on the 1,725 islands of the Philippines. He denounced Aguinaldo as “an irresponsible Chinese Mestizo” (Aguinaldo’s maternal grandfather was Chinese) and a “self-seeking dictator of the ordinary half-breed type” leading one portion of a tribe in rebellion. Theodore Roosevelt compared the Filipino insurgency to the Indian wars when he accepted the Republican vice-presidential nomination in 1900; the parallels, he declared, were so “exact” that self-government to the Philippines “would be like granting self-government to an Apache reservation under some local chief.” War correspondent John Bass shared some of the racial views of the expansionists, but was less confident that the use of force in the Philippines would succeed. Writing in Harper’s Magazine about the Moros or Muslims of the islands of Sulu and Mindinao, he predicted that these people, like the Native Americans, would succumb eventually to the superior race. In the meantime, although their “land of promise” could flourish with tobacco and coffee plantations, it was best to leave the Moros with their wives and their Koran alone, concluded Bass. If they were forced to change, he correctly predicted, they would fight.40

Much was made of manly duty. In Madison, Wisconsin, McKinley announced that, since the army and navy had “brought us” new territories, Americans must meet their responsibilities “with manly courage, respond in a manly fashion to manly duty, and do what in the sight of God and man is just and right.” Theodore Roosevelt, advocate of the strenuous life, insisted that military service toughened American manhood, which too much civilization tended to undermine. American men, in particular, had an obligation to set an example. “The eyes of the world are upon us,” declared Philippines Commissioner Dean C. Worcester, recalling Puritan founder John Winthrop in a speech before prominent Chicagoans. Quoting Rudyard Kipling’s new poem, “The White Man’s Burden,” Worcester called for Americans to take up their imperial responsibilities over their “new-caught, sullen peoples, half-devil and half-child.”41

As later recalled by a minister, McKinley’s most quoted explanation for his Philippines policy was oddly personal. Speaking to a delegation of Methodists in 1899, he insisted that he had not wanted the Philippines and “when they came to us, as a gift from the gods, I did not know what to do with them.” He described praying on his knees for guidance when it came to him that it would be “cowardly and dishonorable” to give the islands back to Spain, “bad business” to give them to commercial rivals Germany and France, and impossible to leave them to “anarchy and misrule” under unfit Filipinos. “There was nothing left for us to do,” he concluded, “but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them.” In this account of divine guidance, McKinley neglected to mention that many Filipinos were Roman Catholic or that the Philippines had a university older than Harvard. This explanation, nevertheless, summed up the key principled, pragmatic, and prejudiced justifications of the president’s imperial policy.42

Anti-imperialists also cited principles and national self-interest to argue against U.S. policy in the Philippines. To state the opposing position, Collier’s Weekly invited Republican George F. Hoar, the respected senior Senator of Massachusetts and Lodge’s counterpart. The debate, Hoar argued, was between republic and empire, between liberty and slavery, between the Declaration of Independence and imperialism. Standing by its traditional principles, the United States had become “the strongest, freest, richest nation on the face of the earth.” Americans would deny their own heritage, he asserted, if instead of dealing with the people of the Philippines as Christians who desired independence, they treated them as “primitives to be subdued so that their land might be used as a stepping-stone to the trade of China.” Other anti-imperialists used satire to contrast U.S. policy with Christian values. William Lloyd Garrison, Jr., the son of the noted abolitionist, rewrote a popular hymn.

Then onward, Christian soldier! Through field of crimson gore,

Behold the trade advantages beyond the open door!

The profits on our ledgers outweigh the heathen loss;

Set thou the glorious stars and stripes above the ancient cross!

The New York Evening Post justified such opposition, saying, “Anti-Imperialism is only another name for old-fashioned Americanism.”43

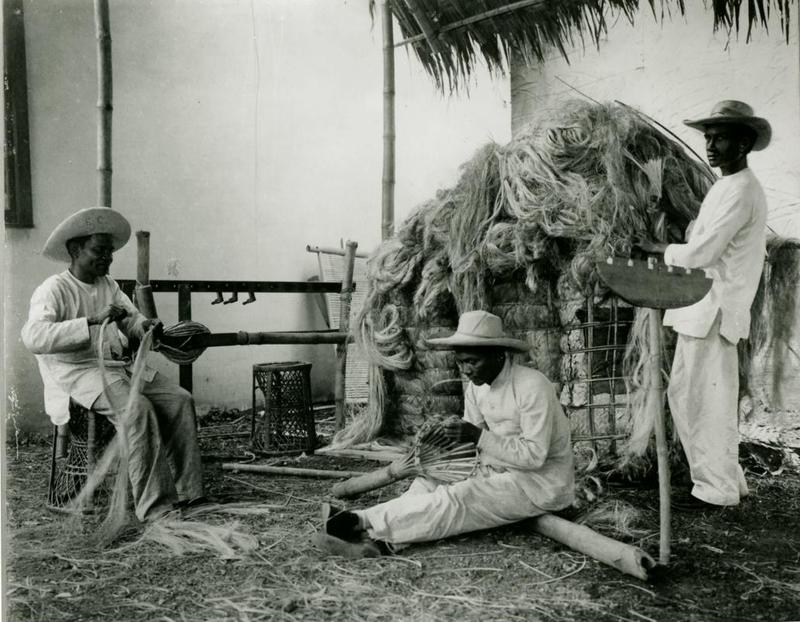

For imperialists and anti-imperialists interested in expanding American trade in the Pacific, the debate centered on the question whether the Filipinos on their own were capable of providing the Americans with the economic opportunities they wanted. In his Annual Message, now called the State of the Union address, President McKinley told the nation that the Filipinos “are a race quick to learn,” but “should be helped … to a more scientific knowledge of the production of coffee, india rubber, and tropical products, for which there is demand in the United States.” The anti-imperialist Senator George Turner of Washington acknowledged the vast interests in Asia, but pointed out that if Manila became a great trading port, it would be at the expense of American ports on the Pacific coast. “It will profit principally a motley population of foreigners, for whom we care nothing,” Turner concluded. He suggested that, by letting the Filipinos govern themselves, the United States could then make commercial treaties with the islands without the burdens of governing. Even Senator Hoar desired access to the Pacific; he simply objected to the means by which the United States was obtaining it. So did the editors of Harper’s Weekly, who felt that the United States had made a mistake in the Philippines. Echoing the president, however, they concluded that once the country was at war, everyone must pull together to support the troops.44

Also fueling anti-imperialist anger was the perception that the administration had abused its power and deceived the public. Senator Hoar believed that the American people had been misled when they were told that the Filipinos were “barbarous and savage” and had made “an unprovoked attack … upon our flag.” Referring to “McKinley’s War,” anti-imperialists charged the president with waging war by military authority, not a congressional declaration. Mark Twain thought that the American people and the Filipinos were being “sold a bill of goods,” featuring two different brands of civilization. “For home consumption,” he thought, the “blessings of civilization”—justice, gentleness, Christianity, law and order, temperance, liberty, equality, education—were prettily and attractively displayed. For export to “the heathen market,” in contrast, “civilization” meant blood, tears, destruction, and loss of freedom. The war, he felt, betrayed the Filipinos and the “clean young men” sent to fight them. Twain tried to imagine what the Filipinos thought: “There must be two Americas: one that sets the captive free, and one that takes a once-captive’s new freedom away from him, and picks a quarrel with him with nothing to found it on; then kills him to get his land.” He said he wished he could see how the United States was going to get out of what had become “a mess, a quagmire.”45

The debate over the war became more politicized in the 1900 presidential election. The Democratic candidate William Jennings Bryan called for Congress to consider granting independence to the Philippines. Anti-imperialist and philosopher William James hoped that if the Filipinos held out long enough, Americans would come to their senses and reject “imperialism and the idol of a national destiny, based on marital excitement and mere ‘bigness.’” The administration and the military condemned the anti-imperialists for, as they saw it, encouraging the Filipinos to resist by denouncing U.S. policies. Taft thought with justification that the insurgents would fight on in hope of a Democratic victory in November.46 Bryan centered much of his campaign on the Philippine issue, declaring it a betrayal of principles and a violation of the sacred mission of America. McKinley spoke of jobs and economic growth. Roosevelt, with his escort of armed cowboys, campaigned for virile, nationalistic Republicanism. At his second inauguration in March 1901, McKinley began his speech talking about currency and ended with the Philippines. “We are not waging war against the inhabitants of the Philippine Islands. A portion of them are making war against the United States,” he declared. “By far the greater part of the inhabitants recognize American sovereignty and welcome it as a guaranty of order and of security for life, property, liberty, freedom of conscience, and the pursuit of happiness.”47

After McKinley’s re-election, U.S. forces escalated the repression. In May 1900, Otis had been succeeded by MacArthur who rejected “benevolent assimilation” and with it the belief that most Filipinos really wanted American rule. In December, MacArthur ordered U.S. forces to wage war against the civilian population in hostile areas. The Americans employed torture, executed prisoners, raped women, looted villages, and destroyed the rural economy. The most effective way to punish a guerrilla fighter, explained General Robert P. Hughes, was to attack his women and children. Funston tricked Aguinaldo into surrender by pretending to be a prisoner of disguised Filipino scouts, entering the leader’s camp, and taking him captive. Aguinaldo called for the end of resistance; several of his generals surrendered and many guerrillas went home. Where the fighting continued, both sides carried out atrocities. In Batangas province in 1901 and 1902, the Americans used reconcentration camps that had caused such outrage when Spain used them in Cuba. An estimated 200,000 Filipinos died from disease and starvation. The punitive policies succeeded in breaking the resistance. Colonel Arthur Murray, who had opposed brutal actions that would make enemies out of civilians assumed to be friendly, concluded that if he had it to do over, he would have had done “a little more killing and considerably more burning.”48

The conciliation side of U. S. policy was the responsibility of Taft, who was confident of the ability of the United States to bring justice and order to the islands. He believed that once laws governing land, mining, banking, and transportation were in place and schools, roads, and hospitals were built, enterprise and prosperity would follow. Yet, he was dogged by problems everywhere. The Filipinos were ignorant and superstitious, he reported. “We shall have to do the best we can with them.” Taft’s deeper frustrations were reserved for his fellow Americans. He condemned the U.S. military officers who treated the Filipinos with cruelty and prejudice, because such behavior inspired more recruits for the insurgents. To Secretary of War Elihu Root, Taft complained about the behavior of U. S. civilians. “You know we have the rag tag and bob tail of Americans, who are not only vicious but stupid,” wrote Taft. “They are most anxious to have Congress give an opportunity to open this country and develop it, but instead of facilitating a condition of peace and good feeling between the Americans and the Filipinos, they are constantly stirring up trouble.” Taft, who was trying to win over the Filipino upper class, despaired when a visiting congressman announced at a press interview in Manila that the Filipinos were “nothing but savages, living a savage life and utterly incapable of self government and without the slightest knowledge of what independence is.” The same attitudes about Filipino inferiority that expansionists had expressed to justify the takeover now interfered with the administration’s efforts to carry it out.49

Taft also had to respond to Washington’s concerns about news reports that described Manila as a den of sin, drunkenness, and prostitution. In contrast to the administration’s claims that its purpose was to bring Christian uplift to the Philippines, the occupation of the islands instead seemed to have corrupted the morals of U.S. troops. Taft blamed the negative press for upsetting the people at home, but had to admit the characterization was valid. He defensively noted that Manila at least was more sober than American cities of its size. The army, alarmed by the spread of venereal disease, established a system for examining prostitutes and confining the diseased to hospitals. As historian Kristin Hoganson has noted, such news prompted anti-imperialists to challenge the administration’s portrayal of its policy as a civilizing mission. Critics declared that instead of enhancing masculine nobility, imperialism led to degeneracy or “going native.”50

At home, McKinley concentrated on spreading the word of progress. In his last speech given in September at the 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, New York, the president praised the fair for recording “the world’s advancement.” Extolling industrial growth, commercial advantage, and new communications technology, he declared, “Isolation is no longer possible or desirable.” For the instruction and entertainment of millions of fair-goers, the fair directors constructed a Filipino Village–their idealized version of the Philippines–alongside Mexican, Hawaiian, Cuban, Eskimo, and Japanese villages. To enter the eleven-acre Filipino Village, fair-goers passed U.S. soldiers on parade at the gates. Once inside they saw one hundred Filipinos at work and play, thatched huts, water buffalo pulling carts, a Catholic church, and a theater where a Filipino band played “The Star-Spangled Banner.” The organizers included representatives of the more “primitive tribes” having decided against putting Aguinaldo on display. The exposition’s artificial global order was shattered when Leon Czolgosz, an anarchist and the son of Polish immigrants, shot the president. After McKinley died eight days later, anarchists and socialists were arrested around the country, demands escalated for immigration restriction, and the price of souvenirs at the exposition skyrocketed.51

Theodore Roosevelt’s administration defended the ongoing conflict in the Philippines and the extreme methods used to fight it. Under pressure from Senator Hoar, the Senate investigated the conduct of the war in April and May 1902. News stories of the reconcentration program and torture practices had appeared in the press. Anti-imperialists bypassed military censorship in the Philippines by publishing eye-witness accounts of atrocities reported by returning soldiers. Chaired by Senator Lodge, the hearings led to light fines for a few officers and a court martial for General Jacob H. Smith, who had ordered his troops to kill every person over ten years old on the island of Samar, which ended in a reprimand. Lodge said that he regretted the atrocities but blamed American behavior on Filipino culture. “I think they have grown out of the conditions of warfare, of the war waged by the Filipinos themselves, a semicivilized people, with all the tendencies and characteristics of Asiatics, with the Asiatic indifference to life, with the Asiatic treachery and the Asiatic cruelty, all tinctured and increased by three hundred years of subjection to Spain,” he explained. Roosevelt dismissed reports of U.S. atrocities, calling the American troops’ behavior at the massacre of the Sioux at Wounded Knee worse. Moreover, he denounced the army’s critics “who walk delicately and live in the soft places of the earth” for dishonoring the “strong men who with blood and sweat” suffered and died “to bring the light of civilization into the world’s dark places.”52

A Century of Selling Empire

On July 4, 1902, President Roosevelt declared the war in the Philippines over. The editors of the Washington Post noted that, between the two of them, Presidents McKinley and Roosevelt had tried to pronounce the war over six times already. The Philippine Commission defined any continuing Filipino insurgence as “banditry.”53 Forty-two hundred Americans had died along with hundreds of thousands of Filipinos. The fighting between Filipinos and Americans continued until 1910 and against the Moros on Mindinao until 1935. Six years later, in December 1941, the Japanese attacked the Philippines and defeated U.S. forces led by General Arthur MacArthur’s son, General Douglas MacArthur, who vowed to return and liberate the islands. Aguinaldo, his father’s old adversary, sided with the Japanese. After World War II, the United States granted the Philippines independence on July 4, 1946, but kept major naval and air bases on the islands until the early 1990s. Aguinaldo, ever the survivor, marched in the first Philippine Independence Day parade waving the revolutionary flag he first had raised in 1898.

President McKinley had announced a new global role for the United States when he acquired the Philippines. The United States ran its colony in the interests of powerful Americans, specifically those with influence in Washington. “Any connection between these interests and those of the Filipino people at large—or, for that matter, of the American people at large—was basically coincidental,” concluded historian H. W. Brands. The United States had become a Pacific power, but the costs of running a colony exceeded the profits. The experience of the Americans in the Philippines reinforced their preference for economic expansion in Asia without direct imperialism. McKinley nevertheless did not hesitate to assert U.S. interests. For instance, in 1900, the president dispatched 5000 American troops from the Philippines to China to join the other imperial powers who were dedicated to putting down the Chinese government-backed rebellion against foreign influence known as the Boxer Rebellion. By ordering U.S. forces to fight overseas against a recognized government without congressional approval, McKinley had created a new presidential power. And he had proven Senator Lodge to be right. The acquisition of the Philippines meant no other power could “shut the gates of China” on the United States and that included China.54

McKinley, who, according to Root, “always had his way,” claimed to follow the will of the people as he shaped opinion. 55 He established the White House as the producer of news, and through the emerging mass media, delivered his messages which balanced principles and interests with something for almost everyone: gung-ho expansionists, do-gooders and missionaries, businessmen, and flag-waving audiences at train stations across the country. He presented the United States and himself as servants of a higher power, fulfilling an extended version of Manifest Destiny. He declared that “trade follows the flag” and the flag must be honored wherever it waved. Although he spoke of the benefits of new markets and enhanced prestige, McKinley assured Americans that this policy was not mainly one of self-interest. It was a “divine mission” in which Americans took on the responsibility of guiding and protecting Filipinos. Popular films, cartoons, and fair exhibits reinforced the official messages that such a mission meant profit and glory. At the same time, such assertions of America’s moral and material superiority were challenged by a drawn-out war, heavy loss of life, and reports of atrocities. Critics expressed concern that war for empire could damage the republic. And the argument made by anti-imperialists–that Americans should not just preach their democratic traditions overseas but actually practice them–would survive.

With gusto, President Theodore Roosevelt associated American expansion with the progress of civilization. It was the task of the “masterful race,” announced Roosevelt in 1901, to make the Filipinos “fit for self-government” or leave them “to fall into a welter of murderous anarchy.” In his Annual Message of 1902, he asserted that, as civilization had expanded in the last century, warfare had diminished between civilized powers. “Wars with uncivilized powers,” Roosevelt explained, “are largely mere matters of international police duty, essential for the welfare of the world.”56 It would be the job of his successors to define who was civilized and who was not.

To justify interventions elsewhere, future presidents would recall McKinley’s attractive version of U.S. involvement in the Philippines. In 1950, President Harry Truman used the Philippine example to defend U.S. intervention in the Korean War. “We helped the Philippines become independent,” he announced in a radio address, “and we have supported the national aspirations to independence of other Asian countries.” The United States, Truman explained, stood for freedom against communist imperialism. That was why, he announced following the outbreak of war in Korea, he had ordered the expansion of U.S. commitments to the Chinese nationalists on Taiwan, to the French rulers of Vietnam, and to the American-sponsored government of the Philippines, which received U.S. military and CIA advisors along with economic aid to assist it in putting down the radical nationalist Huk movement. Notably, Truman presented these three nationalist struggles in Asia as Cold War conflicts. Such a portrayal required little explanation of what was actually happening in these countries and it positioned the United States as their protector in a global struggle defined by Truman as a battle between freedom and totalitarianism.57

“A new totalitarian threat has risen against civilization,” announced President George W. Bush in a speech before the Philippine Congress in October 2003. “America is proud of its part in the great story of the Filipino people,” declared the president. “Together our soldiers liberated the Philippines from colonial rule.” As he rallied support for U.S. leadership in the global war on terror, Bush asserted that the Middle East, like Asia, could become democratic as illustrated by the Republic of the Philippines six decades ago. Not only did President Bush gloss over the inconvenient facts of the past, but he also put a positive face on the present. Uneasy about instability in the Philippines, Bush announced a joint American-Filipino five-year plan to “modernize and reform” the Philippine military. U.S. policymakers were worried about Abu Sayyaf, a terror group thought to have links to Al Qaeda and Islamic extremism. A few thousand U.S. marines were already in the southern Philippines assisting local forces in fighting an Islamic separatist movement with roots going back to the resistance against the Americans a century before.58

McKinley’s portrayal of American rule in the Philippines as the “advancement of civilization,” and “a guaranty of order and of security for life, property, liberty, freedom of conscience, and the pursuit of happiness” held its appeal. His successors also would manipulate media coverage, present war as a humanitarian mission, and call for support of the troops when the “natives” resisted and criticism on the home front grew louder. The propaganda designed to build support for America’s first land war in Asia created an illusion of the United States as a benevolent liberator that lives on.

Susan A. Brewer is a professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. She is the author of Why America Fights: Patriotism and War Propaganda from the Philippines to Iraq (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009) and To Win the Peace: British Propaganda in the United States during World War II (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997).

Related articles

• Paul Kramer, Guantánamo: A Useful Corner of the World

• Jeremy Kuzmarov, American Police Training and Political Violence: From the Philippines Conquest to the Killing Fields of Afghanistan and Iraq

• Paul A. Kramer, The Military-Sexual Complex:Prostitution, Disease and the Boundaries of Empire during the Philippine-American War

• Paul A. Kramer, The Water Cure. An American Debate on torture and counterinsurgency in the Philippines—a century ago

• Paul A. Kramer, Race-Making and Colonial Violence in the U.S. Empire:The Philippine-American War as Race War

• Catherine Lutz, US Military Bases on Guam in Global Perspective

• Catherine Lutz, US Bases and Empire: Global Perspectives on the Asia Pacific

Notes

1 This article first appeared as Chapter 1, “The Divine Mission”: War in the Philippines,” in Why America Fights: Patriotism and War Propaganda from the Philippines to Iraq (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 14-45 and is reprinted in revised form here with the permission of Oxford University Press.

2 “He is evidently going to make unity—a re-united country—the central thought.” Diary of George B. Cortelyou, 9 December 1898, Box 52, George B. Cortelyou Papers, Library of Congress, Washington, DC; Anders Stephanson, Manifest Destiny: American Expansion and the Empire of Right (New York; Hill and Wang, 1996), 66-111; Matthew Frye Jacobson, Barbarian Virtues: The United States Encounters Foreign Peoples at Home and Abroad, 1876-1917 (New York: Hill & Wang, 2000), 221-65; For an excellent historiography on the United States as empire see Paul A. Kramer, “Power and Connection: Imperial Histories of the United States in the World,” American Historical Review 116 (December 2011): 1348-1391.

3 Ida Tarbell, “President McKinley in War Times,” McClure’s Magazine, July 1898, 209-24; Stephen Ponder, “The President Makes News: William McKinley and the First Presidential Press Corps, 1897-1901,” Presidential Studies Quarterly 24 (Fall 1994): 823-37; For an outstanding collection of political cartoons see Abe Ignacio, Enrique de la Cruz, Jorge Emmanuel, Helen Toribio, The Forbidden Book: The Philippine-American War in Political Cartoons (San Francisco: T’boli Publishing, 2004).

4 James Bryce, The American Commonwealth, vol. 2, 3rd ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1899), 252-54; Henry Adams, The Education of Henry Adams (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1961), 374.

5 Paul M. Kennedy, The Rise and Fall of the Great Powers: Economic Change and Military Conflict from 1500-2000 (New York: Random House, 1987), 150.

6 Walter LaFeber, The American Search for Opportunity, 1865-1913 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 133, 138.

7 Robert Hannigan, The New World Power: American Foreign Policy, 1898-1917 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2002), 1-16; Thomas Schoonover, Uncle Sam’s War of 1898 and the Origins of Globalization (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2003), 98.

8 Robert Hilderbrand, Power and the People: Executive Management of Public Opinion in Foreign Affairs, 1897-1921 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1981), 17-28.

9 Margaret Leech, In the Days of McKinley (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1959), 167-68.

10 Allan R. Millett and Peter Malowski, For the Common Defense: A Military History of the United States of America (New York: Free Press, 1994), 287-88.

11 LaFeber, American Search, 142-43; Lewis L. Gould, The Presidency of William McKinley (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1980), 77.

12 Louis A. Pérez, Jr., The War of 1898: The United States and Cuba in History and Historiography (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 10-12.

13 Hilderbrand, Power and the People, 32.

14 William Allen White, “When Johnny Went Marching Out,” McClure’s Magazine, June 1898, 198-205.

15 Leech, Days of McKinley, 209.

16 Leech, Days of McKinley, 238; Gould, Presidency of William McKinley, 101.

17 Gould, Presidency of William McKinley, 50.

18 Walter Millis, The Martial Spirit (1931; reprinted, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1989), 334.

19 Paul A. Kramer, “Race-Making and Colonial Violence in the U.S. Empire: The Philippine War as Race War,” Diplomatic History 30 (April 2006): 190; Paul A. Kramer, The Blood of Government: Race, Empire, the United States and the Philippines (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 102-5.

20 John Seelye, War Games: Richard Harding Davis and the New Imperialism (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2003), 275; F. W. Hewes, “The Fighting Strength of the United States,” McClure’s Magazine, July 1898, 280-87; Edna Woolman Chase and Ilka Chase, Always in Vogue (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1954), 47.

21 Hilderbrand, Power and the People, 36, 41.

22 William McKinley, Speeches and Addresses of William McKinley: From March 1, 1897 to May 30, 1900 (New York: Doubleday & McClure Co., 1900), 85, 97, 109, 113-14, 124.

23 Gould, Presidency of William McKinley, 132, 139; George B. Waldron, “The Commercial Promise of Cuba, Porto Rico, and the Philippines,” McClure’s Magazine, September 1898, 481-84.

24 H. Wayne Morgan, ed., Making Peace with Spain: The Diary of Whitelaw Reid, September-December 1898 (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1965), 215.

25 McKinley to Secretary of War, transmitted to General Otis, 21 December 1898; Adjutant General to Otis, 21 December 1898; Alger to Otis, 30 December 1898, Box 70, Cortelyou Papers; H. W. Brand, Bound to Empire: The United States and the Philippines (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), 48.

26 Robert L. Beisner, Twelve Against Empire: The Anti-Imperialists, 1898-1900 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985); Roger J. Bresnahan, In Time of Hesitation: American Anti-Imperialists and the Philippine-American War (Quezon City, Philippines: New Day, 1981).