Seeing Through Perception Management

The Berster Case. Part 6.

The jury in Kristina Berster’s case went out on a Monday afternoon in mid-October. By the following day it was obvious that a verdict would not come easily. The jurors in Burlington were snagged on two issues: her fear and the justification for her actions. Had sneaking across the border been necessary to avoid West German repression? They couldn’t decide, and looked to the judge for guidance.

Facing the possibility of a hung jury on the third day of deliberations, Judge Coffrin called them back and read an expanded definition of the “necessity defense.” Fear of harm, he said, could only be a defense if the harm would follow immediately. Having a gun to your head, or facing a tiger, would be enough. But just having a tiger in the neighborhood was no excuse for crossing a border illegally.

Photo: Local protest in the late 70s on the right, Bernie Sanders

Photo: Local protest in the late 70s on the right, Bernie Sanders

Even that didn’t settle it. The jury was still stuck. They asked about conspiracy and listened to testimony excerpts. By Friday afternoon they’d broken Vermont’s record for the length of a jury deliberation.

The verdict, finally delivered by the exhausted group at sundown on October 27, 1978 was a felony and misdemeanor conviction. But Kristina was acquitted on the conspiracy charge.

US Attorney William Gray didn’t consider that a victory. The jurors had sent a message through their mixed verdict that they were looking for a way to acquit her. Thwarted in court, Gray went to the press. Breaking the agreement he had made earlier, he revealed that Kristina once lived in South Yemen. While forced to admit this didn’t prove she was a terrorist, he suggested that it did tend to disprove her innocence of terrorist affiliations.

Faced with partial defeat, he had returned to a desperate line of defense — guilt by association. Presumably, he also understood the potential impact of such a last-minute revelation: a renewed crackdown in West Germany, where the press and authorities were watching and viewed South Yemen as a terrorist training ground.

And so, the trial ended as it began, with front page headlines and twisted facts. Kristina remained a pawn of governments, imprisoned without bail, interrogated by agents from two continents, and labeled by both to justify extreme tactics. In Vermont, the rhetoric had softened. But beyond the state line the smear campaign rolled on.

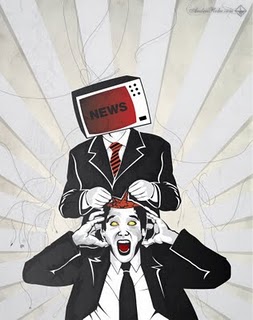

In New York City, a banner headline the day after Berster’s conviction trumpeted, “No Asylum for Terrorist.” That’s how perception management works: When in doubt, just keep on lying.

But the story doesn’t end here. First of all, the jury had reached other conclusions. Some members said afterward that they found Kristina’s situation compelling and expressed hope that a guilty verdict on minor charges wouldn’t prevent her from winning asylum. The following February, the Judge sentenced her to a nine month jail term, all but two weeks of which she’d already served.

Remarking that her story of persecution and flight was credible, Judge Coffrin called for leniency.

It was a strange turn of events, leading some of us to think she might soon be free. But that was not to be. The Immigration and Naturalization Service immediately began deportation proceedings.

By this time, Berster was rightly skeptical that the US would allow her to stay, particularly not as long as it meant defying a close ally. At the time no one represented US interests in Europe more forcefully than the Federal Republic of Germany. From monetary policy and trade to the stationing of nuclear missiles, Germany was to Western Europe what Iran, until the Shah fled, was to the Persian Gulf – a regional policeman. But Germany had committed itself to a policy of “counterterrorism” that threatened civil liberties.

As the 1970s ended, repression was being legalized globally. After the kidnapping of Aldo Moro produced a NATO alert throughout Europe, Germany took the lead, but other countries, including the US, followed suit with their own commando units and “grassroots” networks of spies.

In such a world, what to make of the Kristina Berster case? In one sense, it was a matter of human rights. Victimized by shifting international politics, a student activist whose only crime was crossing a border to seek asylum had spent almost two years in prison, in Germany and then the US.

But there was more to it than that. Berster’s case demonstrated how a campaign against terrorism can easily go off the rails, threatening anyone who actively tries to change the way society is run – from civil libertarians and prison reformers to anti-nuclear protesters and feminists. Across the country, despite claims that the days of COINTEL were over, reports were surfacing – harassment, covert agents provoking violence in nonviolent groups, wiretapping, political grand juries, and intrusive surveillance. As the 1970s wound down a chill was setting in, and terrorism was becoming an excuse for virtually any tactic the government found effective.

Going home in late 1979, Kristina Berster was freed when the original charges against her were dropped. A “complex arrangement” was worked out between the two governments, making it possible for her to voluntarily return without a deportation order.

But her US stay had revealed a few things — for example, that officials, working in and with intelligence agents, were ready to lie in court and sanction illegal surveillance, and that some media could be used to distribute rumors and falsehoods; The evidence remained circumstantial, but it also looked like Vermont had witnessed the manufacturing of a terrorist scare, an attempt to warp public perceptions for political gain. The FBI had lied, so had the prosecutor. Anyone who supported the defendant was targeted for surveillance. Then there was the simulated terrorist “siege.”

In essence, it looked like a concerted effort to influence public opinion, what would soon be labeled “perception management” in a Defense Department manual. Basically, this tactic involves both conveying and denying information “to influence emotions, motives, and objective reasoning.” The goal is to influence both enemies and friends, ultimately to provoke the behavior you want. “Perception management combines truth projection, operations security, cover and deception, and psychological operations,” according to DOD.

In the Reagan years this type of operation was euphemistically labeled “public diplomacy,” which was officially expanded to include domestic disinformation during the Bush I administration. In those days it was mostly about stoking fear of communism, the Sandinistas, Qaddafi, and anyone else on Reagan’s hit list. Clinton modifications were outlined in Directive 68, which still showed no distinction between what could be done abroad and at home. When Bush II took office, the name was changed again, this time to “strategic influence.”

Covering such stories can have costs, like being watched, losing your job, or much worse. In this case, at least the true story did get out in progressive publications, although The Village Voice bought it, then sent a kill fee at the last minute. Columnist Alex Cockburn told me there were two reasons: an ownership change at the paper, and a red flag over the suggestion that Andreas Baader might have been murdered in jail.

Back in Burlington, Jim Martin, the editor who fired me, lasted only a few months himself, Before the end of the year I was back, this time as co-editor. More important, a government “perception management” campaign had been attempted — but had basically failed. Somehow, enough people around Vermont had seen through the haze.

Two years later, Burlington elected a socialist mayor.