Russia’s Palmyra Concert Reveals What the West Lacks

In the war on ISIS, only Russia is acting as if there’s something worth fighting for.

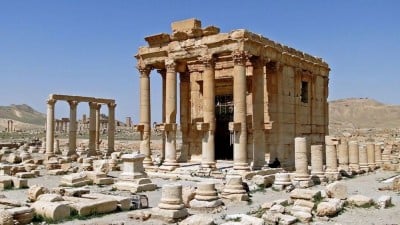

But that was then. ISIS’s 10-month occupation of Palmyra was brought to an end in March when Syrian government forces backed by the Russian military reclaimed it. Now, a very different event has been filmed.

This time, a camera pans round the packed Roman amphitheatre. The audience consisting of Russian ministers, soldiers and an army of journalists, look on, rapt, as the security forces keep watch out of sight. And then, the main event: Bach’s chaconne for solo violin from Partita No2; the quadrille for cello from Shchedrin’sNot Love Alone; Prokofiev’s first symphony… And, as the orchestra from St Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theatre performs the concert of a lifetime, the sound of the ongoing artillery bombardment of ISIS lines less than 10 miles away is drowned out, if only for a few minutes.

As a New York Times journalist admitted, ‘the concert was simply, starkly beautiful, and unfolded as the late afternoon sun faded over the ruins’. In just 30 sublime minutes, it managed to do what the West has failed to do since ISIS pranced on to the global stage two years ago: Russia produced a piece of propaganda to rival ISIS’s tweeted and vlogged barbarism; it allowed a glimpse of the civilisation that it might just be worth fighting for – a sight, amid the ruins of antiquity, of the heights to which humanity can soar. In itself, it was majestic; in context, awe-inspiring.

Yet in the West, the response to the concert has been marked not by awe, but by witless cynicism. It’s as if Western media and politicians are incapable of seeing anything but Russian PR, anything but a shameless attempt to dress up real politikin the garb of high culture. They see only shallow motives, not deep conviction. Those performing were doing so not because of what it meant, it’s suggested, but because of who they knew. So reports tell us that the featured soloist, cellist Sergei Roldugin, is ‘a close friend’ of Russian president Vladimir Putin, and that the conductor, Valery Gergiev, is ‘a Kremlin favourite’. (Reports make little-to-no mention of the fact that Roldugin is also a world-renowned musician, or that Gergiev is a favourite in plenty of other places, too, having been the principal conductor for the London Symphony Orchestra and the director of the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra.) As far as Western media were concerned, ‘[the concert’s] purpose was to assert Russia’s unapologetic might and disdain for Western opinion’. It was no more than, as the Telegraph put it, ‘a bold propaganda stunt’.

Propaganda? Of course, it was propaganda. No one doubts that Russia staged the concert to propagate a certain idea of itself, to endow its largely decisive role in the conflict so far with a grander sense of mission. It wanted to assert itself as the defender not just of a particular regime, or a particular piece of territory, but of something more, too, of something that transcended this particular conflict – as the defender of Western civilisation.

Putin has been positioning Russia as such for a few years now, ‘defending traditional values that have made up the spiritual and moral foundation of civilisation’, as he put it in 2014, largely in opposition to the West’s right-on, rainbow-hued culture war against Eastern Europe. Not that Russia is now the embodiment of the best of Western civilisation. To the gay-friendly, feminist and now transgendered intolerance of the West, Putin’s regime has responded with the traditional, often religious, intolerance of the past. It’s fair to say that Putin’s Russia tends to honour Western Enlightenment values, such as freedom of speech, in the breach rather than the observance.

But the Palmyra concert was not just a shallow pose. It took commitment and conviction; the commitment to pull off the concert, and the conviction that doing so meant something, that performing works by Prokofiev or Bach a few miles away from the frontline in the war against ISIS was worth the risk. Just think about the risk for a moment: a whole orchestra, from the stand-up basses, cellos and other instruments to the musicians themselves, were ferried into a venue that a few weeks ago was being used as an executioner’s stage, and, even now, from which it was still possible to hear the sounds of an artillery bombardment a few miles away. It was propaganda, but that doesn’t mean that what was being propagated was worthless. After all, Russia was prepared to stage a classical-music concert in a warzone to do so.

And that’s why the cynical response of Western pundits and politicians has been so telling. For despite their high-flown blather about the mortal threat posed by ISIS, they can’t conceive of anything about Western civilisation worth the risks Russia took. As they see it, the concert could only have been motivated by something rather less admirable, be it Putin’s vanity, Russian self-aggrandisement or, as UK defence secretary Philip Hammond concluded, something darker. ‘It was a tasteless attempt to distract attention from the continued suffering of millions of Syrians’,suggested Hammond. ‘It shows that there are no depths to which the [Russian] regime will not sink.’

In Hammond’s inability to see the performance as anything other than a subterfuge, one catches sight of something: the reason why Western nations have been unwilling and unable to take the fight to ISIS. The reason, that is, why Russia has emerged as the force most likely to roll ISIS back. Western states don’t lack the means to fight; they lack a sense of what it is they’re fighting for. To Russian ears, a concert in Palmyra resounds with the strains of a long tradition of cultural achievement; to Western ears, it only rings hollow. That’s why Europe and America’s war on ISIS has been so two-faced, with fist-pumping rhetoric about battling ISIS as this ‘imminent threat to every interest we have’ on one side, and, on the other, shady deals with ISIS-facilitating states such as Turkey or Saudi Arabia, and a deep-seated unwillingness to commit troops on the ground. The military capacity’s there, but the bottle’s gone. All talk and no military fatigues. We at spikedhave long noted the nihilism of ISIS, but its wellspring lies in the West itself, in its disavowal of its long-held values and principles, its abandonment of its traditions and heritage, and, now, in its dismissal of an orchestral concert in the ruins of an ancient city.

Tim Black is editor of the spiked review.