Remote Control Warfare. Some Sixty US Drone Bases around the World

Eric Ruder provides the facts about the new weapon of choice for the U.S. war machine–and documents the deadly impact of drones in conflicts around the globe.

ANTIWAR ACTIVISTS are planning actions in April to focus attention on a dark and deadly corner of U.S. military operations: The Pentagon’s and the CIA’s massively scaled-up use of drone aircraft around the world.

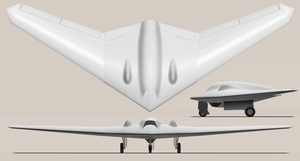

In 2000, the Pentagon had less than 50 drones. Ten years later, that number is 7,500–an increase of 15,000 percent. In 2003, the U.S. Air Force was flying a handful of round-the-clock drone patrols every day. By 2010, that number had reached 40.

“By 2011, the Air Force was training more remote pilots than fighter and bomber pilots combined,” explains Medea Benjamin in her book Drone Warfare: Killing by Remote Control. Benjamin cites Mark Maybury, chief scientist for the Air Force, who said in 2011, “Our number one manning problem in the Air Force is manning our unmanned platform.”

The reasons for the explosion in the use of drones to wage wars around the world are obvious enough. Training drone pilots is faster, less grueling and cheaper compared to traditional pilots. It takes two years to prepare an Air Force recruit for deployment as a pilot, but only nine months to train a drone operator. And, of course, the consequences of drone operator error are no more than the price of the drone itself. As Benjamin writes:

For more information about the April month of action against drone warfare, check out KnowDrones.com and the No Drones Network.

[T]here’s no pilot at risk of being killed or maimed in a crash. No pilot to be taken captive by enemy forces. No pilot to cause a diplomatic crisis if shot down in a “friendly country” while bombing or spying without official permission. If a drone crashes or is shot down, the pilot back home can simply get up and take a coffee break.

But more important is that the use of drones to carry out missions in far-flung countries has enabled the Obama administration to avoid any formal declaration of war while raining down lethal force from the skies–a clear attempt to skirt both U.S. and international law regarding war. As Nick Turse writes in The Changing Face of Empire: Special Ops, Drones, Spies, Proxy Fighters, Secret Bases and Cyberwarfare:

Take the American war in Pakistan–a poster child for what might now be called the Obama formula, if not doctrine. Beginning as a highly circumscribed drone assassination campaign backed by limited cross-border commando raids under the Bush administration, U.S. operations in Pakistan into something close to a full-scale robotic air war, complemented by cross-border helicopter attacks, CIA-funded “kill teams” of Afghan proxy forces, as well as boots-on-the-ground missions by elite special operations forces.

The U.S. has now deployed drones armed with lethal force in Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Somalia and Libya. Some 60 bases throughout the world are directly connected to the drone program–from Florida to Nevada in the U.S., from Ethiopia and Djibouti in Africa, to Qatar in the Middle East and the Seychelles Islands in the Indian Ocean.

According to Turse, for the last three years, Xe Services, the company formerly known as Blackwater, has been in charge of arming the fleet of Predator drones at CIA clandestine sites in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

THE OBAMA administration’s aggressive use of drone warfare is yet further confirmation that Barack Obama’s policies represent the continuation rather than the repudiation of the U.S. government’s militaristic foreign policy of the Bush years.

The withdrawal of combat troops from Iraq–after failing to renegotiate the terms of the Status of Forces Agreement with the Iraqi government–occurred on Obama’s watch, but the U.S. still plans to keep thousands of “non-combat” personnel in Iraq. Meanwhile, Obama carried out a troop surge into Afghanistan that doubled the number of U.S. soldiers in that country.

All along the way, the use of drones has accelerated–especially during Obama’s presidency, as this infographic effectively illustrates. They are seen as the ideal solution for a military that is overextended after 10 years of occupation in Afghanistan and Iraq–without achieving a decisive victory, but at enormous economic, political and diplomatic cost. Drones, by contrast, have a “lightweight footprint,” allowing them to operate behind a veil of secrecy. They provide intelligence, lethal force and global reach on the cheap, while simultaneously giving U.S. military strategists plausible deniability to avoid accountability for their actions.

So when Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) recently blurted out in late February that U.S. drone strikes had killed 4,700 people, the military establishment no doubt shuddered.

Graham was speaking to the Rotary Club in Easley, S.C., and was the first government official to provide a figure for the number of casualties in the drone wars–his number was around one-and-a-half times greater than unofficial estimates based on press accounts and other eyewitness reports.

Of course, Graham wasn’t bemoaning the high death toll–he was enthusiastic about it. Graham went on to say that he approved of the U.S. targeting of American citizens abroad and even the use of drones on the U.S.-Mexico border. Of Anwar al-Awlaki, the U.S. citizen killed in a drone strike in Pakistan in 2011, Graham said, “He’s been actively involved in recruiting and prosecuting the war for al-Qaeda. He was found in Yemen, and we blew him up with a drone. Good.”

“I didn’t want him to have a trial,” he continued. “We’re not fighting a crime, we’re fighting a war. I support the president’s ability to make a determination as to who an enemy combatant is.”

Opinion polls show that many Americans aren’t as enthusiastic as Graham about drones. According to an article by Joan Walsh at Salon.com:

[W]hile 56 percent of respondents support using drones against “high-level terrorist leaders,” only 13 percent think they should be used against “anyone suspected of being associated with a terrorist group.” And only 27 percent supported using drones “if there was a possibility of killing innocent people.” Another 13 percent opposed the drone program entirely.

Given that only a minority of those killed by drones to date are “high-level leaders”–the New American Foundation estimates it’s as low as 2 percent–Americans may be more skeptical of the policy the more they learn about it.

Still, the military establishment has a secret weapon in the public relations battle to preserve support for its favorite secret weapon–Barack Obama himself. Polling done by political scientist Michael Tesler found that significantly more whites “racial liberals” (a pollster category for liberals who are liberal on questions of race) supported the policy of targeted killings once they were told that the Obama administration had carried out this policy. As Walsh writes:

Only 27 percent of white “racial liberals” in a control group supported the targeted killing policy, but that jumped to 48 percent among such voters who were told Obama had conducted such targeted killings. White “racial conservatives” were more likely than white racial liberals to support the targeted killing policy overall, and Obama’s support for it didn’t affect their opinion.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

THE OBAMA administration is thus the perfect mouthpiece for reestablishing the military’s prestige among a war-weary public–and drones are the perfect vehicle.

In this respect, Obama is bringing U.S. military strategy full-circle, as Turse explains:

In 2001, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld began his “revolution in military affairs,” steering the Pentagon toward a military-lite model of high-tech, agile forces. The concept came to a grim end in Iraq’s embattled cities. A decade later, the last vestiges of its many failures continue to play out in a stalemated war in Afghanistan…In the years since, two secretaries of defense and a new president have presided over another transformation–this one geared toward avoiding ruinous, large-scale land wars, which the U.S. has consistently proven unable to win.

Benjamin’s book sometimes implies that the problem with drones is that they make for “bad foreign policy”–because they make immediate recourse to the use of force less costly and therefore more likely. While this is no doubt true, Turse helps to explain how the use of drones is situated within a larger framework.

Drones are really a symptom, not a cause, of the reorientation of U.S. foreign policy away from the cowboy imperialism of the Bush years.

The U.S. has by far the most lethal and technologically advanced military force on the planet, but with its treasury drained and the rapid rise of global competitors, especially China, the “Obama doctrine” employs different strategies to achieve the same goals: fewer tanks, more spies and special forces; fewer invasions, more secret bases and drones; and whenever possible, offloading direct responsibility for fighting onto proxy forces and friendly (to U.S. interests) well-armed dictators.

The goals of these policies aren’t even the choice of presidents. They are obligations imposed on all nations in a world system built around economic competition. This competition compels nation states to arm themselves for military conflict–or be overrun. And it’s the U.S.–which spends as much as the other countries in the top 20 military spenders combined–that does the lion’s share of overrunning.

So while it’s essential to oppose drones and the various imperial adventures they enable, the economic system that gives rise to military conflict must also be challenged.