Reagan Backed Ex-Dictator Jorge Videla and Argentina’s Dirty War

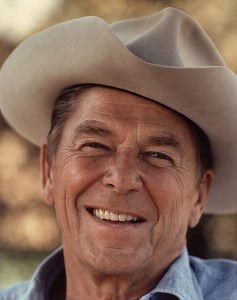

The 87-year-old ex-Argentine dictator Jorge Videla died Friday in prison where he was serving sentences for grotesque human rights crimes in the 1970s and 1980s. But one of Videla’s key backers, the late President Ronald Reagan, continues to be honored by Americans.

The death of ex-Argentine dictator Jorge Rafael Videla, a mastermind of the right-wing state terrorism that swept Latin America in the 1970s and 1980s, means that one more of Ronald Reagan’s old allies is gone from the scene.

Videla, who fancied himself a theoretician of anti-leftist repression, died in prison at age 87 after being convicted of a central role in the Dirty War that killed some 30,000 people and involved kidnapping the babies of “disappeared” women so they could be raised by military officers who were often implicated in the murders of the mothers.

The leaders of the Argentine junta also saw themselves as pioneers in the techniques of torture and psychological operations, sharing their lessons with other regional dictatorships. Indeed, the chilling word “disappeared” was coined in recognition of their novel tactic of abducting dissidents off the streets, torturing them and then murdering them in secret – sometimes accomplishing the task by chaining naked detainees together and pushing them from planes over the Atlantic Ocean.

With such clandestine methods, the dictatorship could leave the families in doubt while deflecting international criticism by suggesting that the “disappeared” might have traveled to faraway lands to live in luxury, thus combining abject terror with clever propaganda and disinformation.

To pull off the trick, however, required collaborators in the U.S. news media who would defend the junta and heap ridicule on anyone who alleged that the thousands upon thousands of “disappeared” were actually being systematically murdered. One such ally was Ronald Reagan, who used his platform as a newspaper and radio commentator in the late 1970s to minimize the human rights crimes underway in Argentina – and to counter the Carter administration’s human rights protests.

For instance, in a newspaper column on Aug. 17, 1978, some 2½ years into Argentina’s Dirty War, Reagan portrayed Videla’s junta as the real victims here, the good guys who were getting a bad rap for their reasonable efforts to protect the public from terrorism. Reagan wrote:

“The new government set out to restore order at the same time it started to rebuild the nation’s ruined economy. It is very close to succeeding at the former, and well on its way to the latter. Inevitably in the process of rounding up hundreds of suspected terrorists, the Argentine authorities have no doubt locked up a few innocent people, too. This problem they should correct without delay.

“The incarceration of a few innocents, however, is no reason to open the jails and let the terrorists run free so they can begin a new reign of terror. Yet, the Carter administration, so long on self-righteousness and frequently so short on common sense, appears determined to force the Argentine government to do just that.”

Rather than challenge the Argentine junta over the thousands of “disappearances,” Reagan expressed concern that the United States was making a grave mistake by alienating Argentina, “a country important to our future security.”

He mocked U.S. Ambassador Raul Castro who “mingles in Buenos Aires plazas with relatives of the locked-up suspected terrorists, thus seeming to legitimize all their claims to martyrdom. It went unreported in this country, but not a single major Argentine official showed up at this year’s Fourth of July celebration at the U.S. Embassy – an unprecedented snub but hardly surprising under the circumstances.”

The Cocaine Connection

Reagan’s Argentine friends also took the lead in devising ways to fund the anti-communist crusade through the drug trade. In 1980, the Argentine intelligence services helped organize the so-called Cocaine Coup in Bolivia, deploying neo-Nazi thugs to violently oust the left-of-center government and replace it with generals closely tied to the early cocaine trafficking networks.

Bolivia’s coup regime ensured a reliable flow of coca to Colombia’s Medellin cartel, which quickly grew into a sophisticated conglomerate for smuggling cocaine into the United States. Some of those drug profits then went to finance right-wing paramilitary operations across the region, according to U.S. government investigations.

For instance, Bolivian cocaine kingpin Roberto Suarez invested more than $30 million in various right-wing paramilitary operations, according to U.S. Senate testimony in 1987 by an Argentine intelligence officer, Leonardo Sanchez-Reisse. He testified that the Suarez drug money was laundered through front companies in Miami before going to Central America, where Argentine intelligence helped organize a paramilitary force, called the Contras, to attack leftist-ruled Nicaragua.

After defeating President Carter in Election 1980 and becoming President in January 1981, Reagan entered into a covert alliance with the Argentine junta. He ordered the CIA to collaborate with Argentina’s Dirty War experts in training the Contras, who were soon rampaging through towns in northern Nicaragua, raping women and dragging local officials into public squares for executions. Some Contras also went to work in the cocaine-smuggling business. [See Robert Parry’s Lost History.]

Much as he served as a pitch man for the Argentine junta, Reagan also deflected allegations of human rights violations by the Contras and various right-wing regimes in Central America, including Guatemala where another military junta was engaging in genocide against Mayan villages.

The behind-the-scenes intelligence relationship between the Argentine generals and Reagan’s CIA puffed up Argentina’s self-confidence so much that the generals felt they could not only continue repressing their own citizens but could settle an old score with Great Britain over control of the Falkland Islands, what the Argentines call the Malvinas.

Even as Argentina moved to invade the islands in 1982, the Reagan administration was divided between America’s traditional alliance with Great Britain and its more recent collaboration with the Argentines. Reagan’s U.N. Ambassador Jeane Kirkpatrick joined the Argentine generals for an elegant state dinner in Washington.

Finally, however, Reagan sided with British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher whose counterattack drove the Argentines from the islands and led to the eventual collapse of the dictatorship in Buenos Aires. However, Argentina only slowly began to address the shocking crimes of the Dirty War.

Baby Snatching

The trial of Videla and co-defendant Reynaldo Bignone for the baby snatching did not end until 2012 when an Argentine court convicted the pair in the scheme to murder leftist mothers and farm their infants out to military personnel, a shocking process that was known to the Reagan administration even as it worked closely with the bloody regime in the 1980s.

Testimony at the trial included a videoconference from Washington with Elliott Abrams, Reagan’s Assistant Secretary of State for Latin American Affairs who said he urged Bignone to reveal the babies’ identities as Argentina began a transition to democracy in 1983. Abrams said the Reagan administration “knew that it wasn’t just one or two children,” indicating that U.S. officials believed there was a high-level “plan because there were many people who were being murdered or jailed.”

A human rights group, Grandmothers of the Plaza de Mayo, says as many as 500 babies were stolen by the military during the repression from 1976 to 1983.

General Videla was accused of permitting – and concealing – the scheme to harvest infants from pregnant women who were kept alive in military prisons only long enough to give birth. According to the charges, the babies were taken from the new mothers, sometimes after late-night Caesarean sections, and then distributed to military families or sent to orphanages.

After the babies were pulled away, the mothers were removed to another site for their executions. Some were put aboard death flights and pushed out of military planes over open water.

One of the most notorious cases involved Silvia Quintela, a leftist doctor who attended to the sick in shanty towns around Buenos Aires. On Jan. 17, 1977, Quintela was abducted off a Buenos Aires street by military authorities because of her political leanings. At the time, Quintela and her agronomist husband Abel Madariaga were expecting their first child.

According to witnesses who later testified before a government truth commission, Quintela was held at a military base called Campo de Mayo, where she gave birth to a baby boy. As in similar cases, the infant then was separated from the mother.

What happened to the boy is still not clear, but Quintela reportedly was transferred to a nearby airfield. There, victims were stripped naked, shackled in groups and dragged aboard military planes. The planes then flew out over the Rio de la Plata or the Atlantic Ocean, where soldiers pushed the victims out of the planes and into the water to drown.

According to a report by the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the Argentine military viewed the kidnappings as part of the larger counterinsurgency strategy.

“The anguish generated in the rest of the surviving family because of the absence of the disappeared would develop, after a few years, into a new generation of subversive or potentially subversive elements, thereby not permitting an effective end to the Dirty War,” the commission said in describing the army’s reasoning for kidnapping the infants of murdered women. The kidnapping strategy conformed with the “science” of the Argentine counterinsurgency operations.

According to government investigations, the military’s intelligence officers also advanced Nazi-like methods of torture by testing the limits of how much pain a human being could endure before dying. The torture methods included experiments with electric shocks, drowning, asphyxiation and sexual perversions, such as forcing mice into a woman’s vagina. Some of the implicated military officers had trained at the U.S.-run School of the Americas.

The Argentine tactics were emulated throughout Latin America. According to a Guatemalan truth commission, the right-wing military there also adopted the practice of taking suspected subversives on death flights, although over the Pacific Ocean.

Spinning Terror

Gen. Videla, in particular, took pride in his counterinsurgency theories, including clever use of words to confuse and deflect. Known for his dapper style and his English-tailored suits, Videla rose to power amid Argentina’s political and economic unrest in the early-to-mid 1970s.

“As many people as necessary must die in Argentina so that the country will again be secure,” he declared in 1975 in support of a “death squad” known as the Argentine Anti-Communist Alliance. [See A Lexicon of Terror by Marguerite Feitlowitz.]

On March 24, 1976, Videla led the military coup which ousted the ineffective president, Isabel Peron. Though armed leftist groups had been shattered by the time of the coup, the generals still organized a counterinsurgency campaign to wipe out any remnants of what they judged political subversion.

Videla called this “the process of national reorganization,” intended to reestablish order while inculcating a permanent animosity toward leftist thought. “The aim of the Process is the profound transformation of consciousness,” Videla announced.

Along with selective terror, Videla employed sophisticated public relations methods. He was fascinated with techniques for using language to manage popular perceptions of reality. The general hosted international conferences on P.R. and awarded a $1 million contract to the giant U.S. firm of Burson Marsteller. Following the Burson Marsteller blueprint, the Videla government put special emphasis on cultivating American reporters from elite publications.

“Terrorism is not the only news from Argentina, nor is it the major news,” went the optimistic P.R. message. Since the jailings and executions of dissidents were rarely acknowledged, Videla felt he could count on friendly U.S. media personalities to defend his regime, people like former California Gov. Ronald Reagan.

In a grander context, Videla and the other generals saw their mission as a crusade to defend Western Civilization against international communism. They worked closely with the Asian-based World Anti-Communist League and its Latin American affiliate, the Confederacion Anticomunista Latinoamericana [CAL].

Latin American militaries collaborated on projects such as the cross-border assassinations of political dissidents. Under one project, called Operation Condor, political leaders — centrist and leftist alike — were shot or bombed in Buenos Aires, Rome, Madrid, Santiago and Washington. Operation Condor sometimes employed CIA-trained Cuban exiles as assassins. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “Hitler’s Shadow Reaches toward Today,” or Robert Parry’sSecrecy & Privilege.]

For their roles in the baby kidnappings, Videla, who was already in prison for other crimes against humanity, was sentenced to 50 years; Bignone received 15 years.

Earlier in May, Guatemala’s ex-dictator Efrain Rios Montt, another close ally of Ronald Reagan, was convicted of genocide against Mayan Indians in 1982-83 and was sentenced to 80 years in prison. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “Ronald Reagan: Accessory to Genocide.”]

Yet, while fragile democracies in places like Argentina and Guatemala have sought some level of accountability for these crimes against humanity, the United States continues to honor the principal political leader who aided, abetted and rationalized these atrocities across the entire Western Hemisphere, the 40th President of the United States, Ronald Reagan.

Investigative reporter Robert Parry broke many of the Iran-Contra stories for The Associated Press and Newsweek in the 1980s. You can buy his new book, America’s Stolen Narrative, either in print here or as an e-book (from Amazon and barnesandnoble.com).