Not Saving Private Ryan: The Murderous Finale of the Great War. November 11, 1918, One Hundred Years Ago

An excerpt from Jacques R. Pauwels, The Great Class War 1914-1918, James Lorimer, Toronto, 2016

[Fall 1918, after the failure of the German final offensive:] The majority of the German soldiers on the western front realized that the war was lost, they wanted to get it over and done with, and go home. And they did not hide their contempt for the political and military leaders who had unleashed the conflict and thus caused so much misery. They were not willing to lose their lives for a lost cause.

The German army began to disintegrate, discipline broke down, and the number of desertions and mass surrenders skyrocketed. Some German historians have described this situation as a Kampfstreik, an undeclared “military strike” or “refusal to fight,” a “refusal to carry on with the war.”

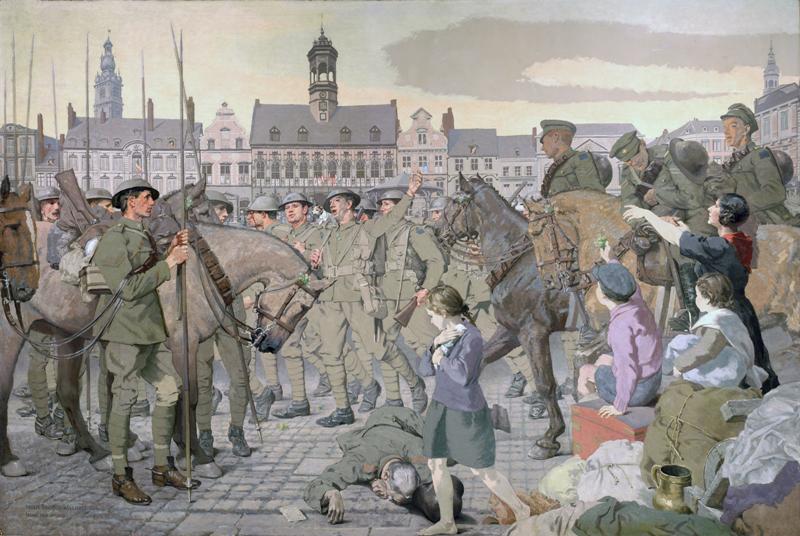

Canadian troops arriving in Mons, November 11, 1918 (painting by Inglis Sheldon-Williams, “The Return to Mons”, Canadian War Museum Ottawa CWM 19710261-0813, c/o Wikimedia Commons)

Between mid-July 1918 and the armistice of November 11 of that year, 340,000 Germans surrendered or ran over to the enemy. In September 1918, a Tommy witnessed how German POWs laughed and applauded each time a new contingent of prisoners was brought in. Even elite soldiers capitulated in large numbers. Of the German losses at that time, prisoners represented an unprecedented 70 per cent. The German soldiers now used all kinds of tricks to avoid going to the front, a practice that became known as Drückebergerei, “shirking.” Many men who were transferred from Eastern Europe to the western front crossed into the neutral Netherlands in order to be able to await there the end of the war as internees. No less than 750,000 German soldiers allegedly deserted at that time; and just about as many were simply reported as “absent” from their unit. The number of deserters hanging around in the capital, Berlin, was estimated by the police to be in the tens of thousands.

The epidemic of desertions, mass surrenders, and shirking mushroomed during August and September 1918, so much so that this state of affairs has been described as an “undeclared military strike.” And that is certainly how the “front swine” [German soldiers] themselves saw things. The soldiers who were leaving the front often insulted men that were marching in the opposite direction, calling them “strike breakers” and Kriegsverlängerer, “war prolongers”! The influence of the Russian Revolution in all this became obvious when, in October, the sailors stationed in the port of Kiel mutinied. They refused to obey orders — especially an absurd order for the fleet to undertake a suicidal sortie against the Royal Navy — and set up councils of soldiers and workers; in other words, Russian-style soviets. Similar councils soon emerged all over Germany.

Under these circumstances, it amounted to a miracle that the Germans managed to put up an ordered and relatively effective resistance when their enemies launched a final offensive toward the end of the summer and in the fall of 1918. They had to withdraw, and did so, but slowly and in good order. Until the bitter end, the Great War thus remained the murderous enterprise it had been from the start. During the last five weeks of the war, half a million men were still killed or wounded. Even the very last day saw heavy casualties being inflicted on both sides. Some soldiers “fell” only minutes before the armistice went into effect on November 11 at 11 a.m. On November 10, British and Canadian troops arrived on the outskirts of the Belgian town of Mons, where in August 1914 the British forces had first faced the Germans in a battle. Late at night, a message reached the local commanders. In Rethondes, a hamlet in a forest near Compiègne, where General Foch, supremo of the allied armies, had installed his headquarters, an agreement had been reached with German emissaries to lay down the arms later that same day, namely at 11 a.m. The British poet May Wedderburn Cannan has saluted this long-awaited announcement in a poem entitled “The Armistice”:

The news came through over the telephone: All the terms had been signed: the war was won And all the fighting and the agony, And all the labour of the years were done.

At Mons, however, the fighting and agony were not done yet. The men could have enjoyed a leisurely breakfast and waited until 11 before sauntering into the town. However, the Canadian commander, General Arthur Currie, gave the order to take Mons early in the morning, knowing very well that the Germans would resist and that blood would flow. “It was a proud thing,” he was to explain later, “that we were able to finish the war there where we began it, and that we, the young [Canadian] whelps of the old [British] lion, were able to take the ground lost in 1914.” But his subordinates saw things quite differently. Two Canadian historians describe their reaction:

[They] openly questioned the need to advance any further . . . None of [them] wanted any part of the Mons show. They were all grumbling to beat hell. They knew the war was coming to an end and there was going to be an armistice. ‘What the hell do we have to go any further for?’ they grumbled . . . At the end of the day the men were furious about the losses.”

These losses included George Ellison and George Price, respectively the last Tommy and the last Canadian to “fall” in the Great War; they were killed within minutes before the arms were laid down. They rest in the British-German war cemetery of Saint-Symphorien, a few kilometres outside of Mons, together with John Parr, the very first British soldier to lose his life in the Great War. Hundreds of other British, Germans, and Canadians perished in and around Mons in the early stages and in that war’s final minutes. However, the very last soldier to be killed in the Great War was an American of German origin, named Henry Gunther; he fell in the village of Chaumont-devant-Damvillers, situated to the north of Verdun, just one minute before the end.

Exhausted soldiers after a battle in World War I

(photo from the Imperial War Museums)

On the last day of the Great War, November 11, 1918, all armies combined suffered 10,944 casualties on the western front, including 2,738 men killed. This was approximately twice the daily average of killed and wounded during 1914–1918. (It was also about 10 per cent more than the total casualties on D-Day, the first day of the landings in Normandy in June 1944.)

This bloodshed could have been avoided if the French and allied commander-in-chief, Marshal Foch, had not refused to accept the German negotiators’ request to declare a ceasefire as soon as the capitulation was signed in the night, rather than to wait until 11 a.m. In Mons, the disgruntled Canadian soldiers “were exhausted and just wanted a good meal, a hot shower, and a comfortable bed. They were glad the war was over, but for many it was not a cause for celebration because of the many friends they had lost . . .” There were no celebrations other than “some jumping around and things like that,” a soldier reported; and it did not help that the commanders ordered a general inspection, causing the men to have to “stand out six hours in the cold rain.”

With respect to the final minutes of the Great War, a quaint anecdote deserves to be mentioned, even though it may be apocryphal. Shortly before 11 a.m., somewhere on the western front, a German started to fire his machine gun furiously. At precisely 11 he stopped, stood up, took off his helmet, took a bow, and walked quietly to the rear.

Distinguished historian Dr. Jacques Pauwels is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG)

To order Dr. Jacques Pauwels book entitled the Great Class War, 1914-1918, click front cover of book

Historian Jacques Pauwels applies a critical, revisionist lens to the First World War, offering readers a fresh interpretation that challenges mainstream thinking. As Pauwels sees it, war offered benefits to everyone, across class and national borders.

Historian Jacques Pauwels applies a critical, revisionist lens to the First World War, offering readers a fresh interpretation that challenges mainstream thinking. As Pauwels sees it, war offered benefits to everyone, across class and national borders.

For European statesmen, a large-scale war could give their countries new colonial territories, important to growing capitalist economies. For the wealthy and ruling classes, war served as an antidote to social revolution, encouraging workers to exchange socialism’s focus on international solidarity for nationalism’s intense militarism. And for the working classes themselves, war provided an outlet for years of systemic militarization — quite simply, they were hardwired to pick up arms, and to do so eagerly.

To Pauwels, the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914 — traditionally upheld by historians as the spark that lit the powder keg — was not a sufficient cause for war but rather a pretext seized upon by European powers to unleash the kind of war they had desired. But what Europe’s elite did not expect or predict was some of the war’s outcomes: social revolution and Communist Party rule in Russia, plus a wave of political and social democratic reforms in Western Europe that would have far-reaching consequences.

Reflecting his broad research in the voluminous recent literature about the First World War by historians in the leading countries involved in the conflict, Jacques Pauwels has produced an account that challenges readers to rethink their understanding of this key event of twentieth century world history.