Nelson Mandela’s Life: The Film

It has been said that this is the year of the black film. Three have stood out as the Oscar buzz begins in earnest.

First, there was The Butler, later Lee Daniels The Butler, after a studio pissing-match about who owned the title. The heavily rewritten and sanitized story of a black butler in the White House became a platform for celebration as a cast of Hollywood heavyweights led by TV Queen Oprah Winfrey offered a praise poem to civil rights victories in which they included the election of Barack Obama.

Some critics like one at the Daily Mail felt the film was over the top: “It has been given a rather overly generous dashing, as if by a nervous butler, of dramatic license. Not historic license, though. No, every majo development in the civil rights story is ticked off…what you might call the Forrest Gumping of Forest Whitaker.”

The Guardian said it “plays fast and loose with the facts” as the “central character becomes a cipher for the changing fortunes of African Americans in the 20th century.”

The underlying idea: turn civil rights into a feel-good story.

Then, enter British director Steve McQueen with a feel-bad counterpoint, 12 Years A Slave, a retelling of the brutality of slavery. It is a movie about subjugation and victimization. Most of the media loved it except the African-American critic Armond White who was brave but scathing in putting it down, writing:

“Depicting slavery as a horror show, McQueen has made the most unpleasant American movie since William Friedkin’s 1973 The Exorcist. That’s right, 12 Years a Slave belongs to the torture porn genre … but it is being sold (and mistaken) as part of the recent spate of movies that pretend ‘a conversation about race.’ The only conversation this film inspires would contain howls of discomfort.”

Nevertheless, the slavery story has been downplayed over the years — with some recent exceptions, most notably continuing references in Stephen Spielberg’s heroic paen to Lincoln=, and Quentin Tarantino’s mocking Django Unchained that played to the desire for revenge and payback by the ancestors of the victims.

Django became a comic vehicle for laughing at oppressors even as Lincoln aspired to educate Americans about their preferably forgotten tragic past.

Django also plays to the simmering anger and often silent discontent among black Americans who have come to realize how little our first black president has done for their community, plagued as it is by high levels of unemployment, massive foreclosures and pervasive downward mobility.

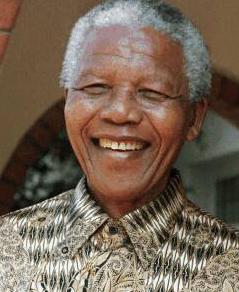

Now, late in the year, comes Mandela Long Walk to Freedom, a real-life majestic bio-pic that deals with the headier subject of liberation.

A South African production with powerful American and European distribution, it captures the sweep of Nelson Mandela’s long life from his childhood days in a rural tribal area to his triumph in the presidential election of l994. It deals openly with some of his flaws and role in an armed struggle denounced as terrorism at the time.

So far, most critics embrace it, especially Idris Elba’s sterling performance as Mandela and Naomie Harris as Winnie, although some sneer at it for being “stolid” or “worthy,” because it covers too much and deals with the political choices of Mandela and the ANC..

In many ways, some of these critics seem to believe their duty is to insure that major movies don’t stray from entertainment formulas and avoid serious issues. This is the kind of sniping that usually greets a film sympathetic to political movements; even this one has conformed to Hollywood narrative demands with a centerpiece portraying the ups and downs of the man South Africans called Madiba and his love affair with Winnie Mandela.

This is a film I know something about personally because I directed a multi-hour Making of, and Meaning of, documentary on the set. Some of my research and more than 100 recent interviews are also the basis of my new soon to be released book, Madiba AtoZ: The Many Faces of Nelson Mandela (Seven Stories Press).

It was commissioned by the movie’s producers because they want the rest of the story told too. It is being distributed—so far—in the U.S., South Africa and China.

So, I am partial to the importance of the underlying history of the triumphant fight against a brutal and slave-like apartheid system that was set up to allow a white minority to dominate the black majority on the basis of racism and white supremacy.

Turning Mandela’s story, based on his autobiography first drafted in prison, into a scipt inevitably requires leaving out a lot to capture the emotional intensity of the story. (Mandela originally asked the Producer who got the rights while he was behind bars if he thought anyone would want to watch a movie about him.

Screenwriter William Nicholson (Gladiator, Sarafina and others) underscores the fact that it is a drama, not a documentary. Happily a documentary was also made.

Making the movie took 15 years of money-raising, with more than 50 drafts of the screenplay and a shifting cast of actors and directors. Great attention was paid to historical detail in the sets and the setting, with period costumes made for the production and antique cars chronicling a life that goes back to 1918. It’s the most expensive film ever made in South Africa.

It is also probably the weightiest and best, given the leading South African actors who have also been cast and the passion I saw in the production as well as among the more than 700 extras that worked on a project they could believe in.

The brilliant Justin Chadwick who made the Kenya-based story First Grader that integrated the suppressed story of the Mau rebellion directs. The formidable South African filmmaker, Anant Singh, produces.

It is not often that third world film companies get to tell their own stories, and get them seen in movie theaters globally.

There have been enthusiastic screenings of Long Walk in South Africa and at film festivals beginning with Toronto. It has premiered in LA, and at New York’s Lincoln Center after a President Obama-hosted screening at the White House, and a bi-partisan Kennedy Center screening in Washington with Hilary Clinton, Colin Powell and Senator John McCain. It is also being shown at special community and school events, as part of an educational curriculum

Mandela Long Walk to Freedom opens in New York and LA at the end of November and then nationwide on Christmas Day. There will be a Royal screening in London and a premiere on January 3, 2014.

For more on the film and the book, see Madibabook.com

News Dissector Danny Schechter blogs at Newsdissector.net and edits News Dissector.net.