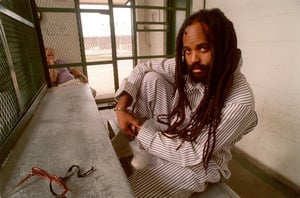

“Mumia Abu-Jamal Live From Death Row”: Why Mumia Matters to the Nation and the World

By John Edgar Wideman, novelist and PENN/Faulkner Award-winner

Recalling the horrors of African-American history, accepting the challenges our history presently places on us, is like acknowledging a difficult, unpleasant duty or debt that’s been hanging over our heads a very long time, an obligation that we know in our hearts we must deal with but that we keep putting off and evading, as if one day procrastination will make the burden, the obligation we must undertake, disappear.

Mumia Abu-Jamal forces us to confront the burden of our history. In one of his columns from death row he quotes at length an 1857 ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court. The issue being determined by the Court is whether the descendants of slaves, when they shall be emancipated, are full citizens of the United States. Chief Justice Roger Taney states:

“We think they are not, and that they were not included, and were not intended to be included, under the word “citizens” in the Constitution, and can therefore claim none of the rights and privileges of the United States . . .” – Justice Taney, speaking for the Court, confirms the judgment of his ancestors and articulates an attitude prevailing to this very day.

Mumia points out that Thurgood Marshall, the first person of African descent appointed to the U.S. Supreme court, admitted, just hours after his resignation from the Court, that “I’m still not free.” . . . Mumia Abu-Jamal’s writing insists on these kinds of gut checks, reality checks. He reminds us that to move clearly in the present, we must understand the burden of our past.

Mumia Offers Models for Struggle

Situated as he is in prison, a prison inside a prison actually, since he’s confined on death row, Mumia Abu-Jamal’s day- to-day life would seem to share little with ours, out here in the so-called free world. Then again, if we think a little deeper, we might ask ourselves – who isn’t on death row? Perhaps one measure of humanity is our persistence in the business of attempting to construct a meaningful life in spite of the sentence of death hanging over our heads every instant of our time on earth.

Although we can’t avoid our inevitable mortality, we don’t need to cower in a corner, waiting for annihilation. Neither should we allow the seemingly overwhelming evil news of the day to freeze us in our tracks, nor let it become an excuse for doing nothing, for denial and avoidance, for hiding behind imaginary walls and pretending nothing can harm us. Alternatives exist. Struggle exists. Struggle to connect, to imagine ourselves better. To imagine a better world. To take responsibility step by step, day by day, for changing the little things we can control, refusing to accept the larger things that appear out of control. The life and the essays of Mumia Abu-Jamal provide us with models for struggle. . . .

The Uniqueness of Mumia’s StoryMumia Abu-Jamal’s voice is considered dangerous and subversive and thus is censored from National Public Radio, to name just one influential medium. Many books about black people, including a slew of briskly selling biographies and autobiographies – from Oprah to O.J. to Maya Angelou – are on the stands.

What sets Mumia’s story apart as so threatening?

It is useful to remember that the slave narrative and its progeny, the countless up-from-the depths biographies and autobiographies of black people that repeat the form and assumptions of the slave narrative, have always been best- sellers. They encapsulate one of the master plots Americans have found acceptable for black lives. These neoslave narratives carry a message the majority of people wealthy enough to purchase books wish to hear.

The message consists of a basic deep structure repeated in a seemingly endless variety of packages and voices. The slave narratives of the 1800s posited and then worked themselves out in a bifurcated, either/or world. The action of the story concerns moving from one world to another. The actor is a single individual, a featured star, and we watch and listen as this protagonist undergoes his or her rite of passage. South to north, rural to urban, black environment (plantation) to white environment (everywhere), including the language in which the narrator converses with the reader), silence to literacy, are some of the classic crossovers accomplished by the protagonists of such fables. If you punch in modern variants of these dichotomies – ghetto to middle class, ignorance to education, unskilled to professional, despised gangster to enlightened spokespersons, you can see how persistent and malleable the formula is.

The formula for the neoslave narrative sells because it is simple; because it accepts and maintains the categories (black/white, for instance) of the status quo; because it is about individuals, not groups, crossing boundaries; because it comforts and consoles those in power and offers a ray of hope to the powerless. Although the existing social arrangements may allow the horrors of plantations, ghettos, and prisons to exist, the narratives tell us, these arrangements also allow room for some to escape. Thus the arrangements are not absolutely evil. No one is absolutely guilty, nor are the oppressed (slave, prisoner, ghetto inhabitant) absolutely guiltless. If some overcome, why don’t others?

Vicarious identification with the narrator’s harrowing adventures, particularly if the tale is told in first person “I”, permits readers to have their cake and eat it too. They experience the chill and thrill of being an outsider. In the safety of an armchair, readers can root for the crafty slave as the slave pits himself against an outrageously evil system that legitimizes human bondage. Readers can ignore for a charmed moment their reliance on the same system to pay for the book, the armchair.

The neoslave narratives thus serve the ambivalent function of their ancestors. The fate of one black individual is foregrounded, removed from the network of systemic relationships connecting, defining, determining, undermining all American lives. This manner of viewing black lives at best ignores, at worst reinforces, an apartheid status quo. Divisive categories that structure the world of the narratives – slave/free, black/white, underclass/middle class, female/male – are not interrogated. The idea of a collective, intertwined fate recedes. The mechanisms of class, race, and gender we have inherited are perpetuated ironically by a genre purporting to illustrate the possibility of breaking barriers and transcending the conditions into which one is born.

Mumia Abu-Jamal’s essays question matters left untouched by most of the popular stories of black lives decorating bookstores today. And therein lies much of the power, the urgency, of his writing.

On Mumia, Defiance and Authentic Freedom

His essays are important as departure and corrective. He examines the place where he is – prison, his status – prisoner, black man, but refuses to accept the notion of difference and separation these labels project. Although he yearns for freedom, demands freedom, he does not identify freedom with release from prison, does not confuse freedom with what his jailers can give or take away, does not restrict the concept of freedom to the world beyond the bars his jailers enter from each day. Although dedicated to personal liberation, he envisions that liberation as partially dependent on the collective fate of black people.

He doesn’t split his world down the middle to conform to the divided world prison enforces. He expresses the necessity of connection, relinquishing to no person or group the power to define him. His destiny, his manhood, is not attached to some desperate, one-way urge to cross over to a region controlled or possessed by others. What he is, who he can become, results from his daily struggle to construct an identity wherever his circumstances place him. . . .

The first truth Mumia tells us is that he ain’t dead yet. And although his voice is vital and strong, he assures us it ain’t because nobody ain’t trying to kill him and shut him up. In fact, just the opposite is true. The power of his voice is rooted in his defiance of those determined to silence him. Magically, Mumia’s words are clarified and purified by the toxic strata of resistance through which they must penetrate to reach us. Like the blues. Like jazz. . . .

Mumia’s Voice as a Key to Our Nation’s Survival

In a new world where African people were transported to labor, die, and disappear, we’ve needed unbound voices to reformulate our destiny – voices refusing to be ensnared by somebody else’s terms. We’ve developed the knack of finding such voices in the oddest, darkest, most unforeseen places. A chorus of them exists in Great Time, the seamless medium uniting past, present, and future. The voices are always there, if we discipline ourselves to pick them out. Listen to them, to ourselves, to the best we’ve managed to write and say and dance and paint and sing.

African-American culture, in spite of the weight, the assault it has endured, may contain a key to our nation’s survival, a key not found simply in the goal of material prosperity, but in the force of spirit, will, communal interdependence.

Because he tells the truth, Mumia Abu-Jamal’s voice can help us tear down walls – prison walls, the walls we hide behind to deny and refuse the burden of our history.

Excerpted with author’s permission from John Edgar Wideman‘s “Introduction”, in Mumia Abu-Jamal, Live from Death Row (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley Pub. Co., 1995).