The Plebiscite: Most Affected Colombians Voted for Peace, Who Voted ‘No’?

The “No” vote won in the Colombian plebiscite on the peace deal recently signed between the government and the FARC-EP, when surveys anticipated that at least two-thirds of voters would approve it.

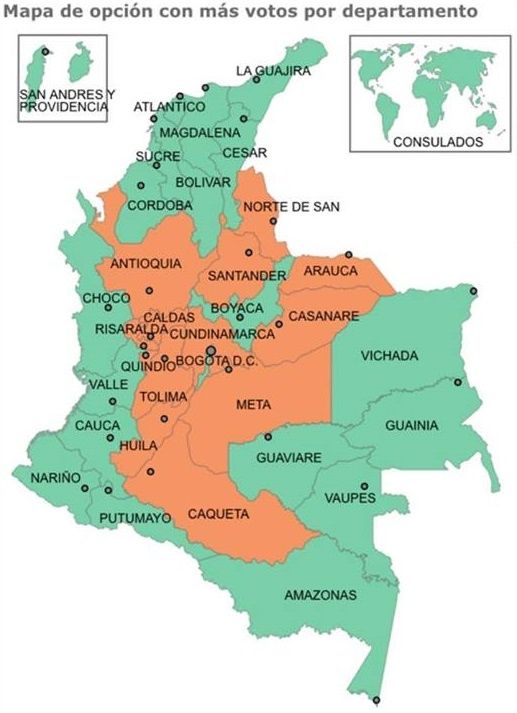

Looking closely at the geographical distribution of the vote, it seems that the “No” vote received more support in Colombian departments that are not as affected by the armed conflict.

Meanwhile, the poorest, rural, Afro-descendent, Indigenous departments—located on the outskirts of the country, including border and Caribbean departments—have overwhelmingly favored a political solution to the conflict because they continue to pay the highest price for the conflict.

Of the major cities, Bogota, the country’s capital, and Cali voted “Yes,” while Medellin, with ties to nacro -trafficking, voted “No.”

“Thanks to the armed conflict, Colombia has been able for years to avoid addressing strong protests or social demands,” said sociologist Daniel Pecaut, in an interview with El Tiempo in June. “The armed conflict has contributed to maintaining the social and political structures of the country, and even to increasing the concentration of land property, as well as the unequal distribution of revenues.”

“Many sectors, not only the governing elites, found out, quite subconsciously, that the armed conflict was not disturbing the cities too much, but only the country’s peripheries,” he said two years earlier to Semana, commenting on the electoral campaign that mostly revolved around the possibility of peace negotiations with the FARC-EP.

As a result, he observed, Colombia has paradoxically had a consistent economic growth in the past 30 years, yet maintaining the same level of social inequality as in the 1930s.

With the recent agrarian strikes that paralyzed Colombia, the ruling sectors of the country started fearing even more—the possibility of social reforms—and the peace deal could create the conditions for such reforms.

Such sectors are represented by former president Alvaro Uribe, known for his close ties with paramilitary groups, who has led a smear and fear-mongering campaign against the peace deal.

“A modern country needs to accept social conflict; this is the price of democracy,” warned Pecaut, who found “extremely worrying” the country’s divisions around the peace deal.