Mongolia as the Key to a Russian-South Korean Strategic Partnership

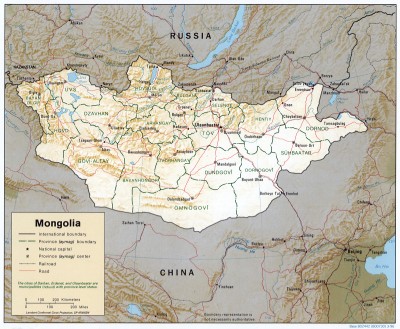

Nestled between Russia and China, Mongolia is a geographically obscure country with the sparsest population density in the world. It isn’t exactly what comes to mind when one thinks of East Asian or Pacific economic opportunities, yet for Russia, Mongolia is the key that it needs to unlock strategic relations with South Korea. Ulaanbaatar’s unique Third Neighbor Policy has allowed it to cultivate favorable relations with Seoul, and coupled with its valuable coal reserves and rare earth minerals, it has just the type of resources that South Korea needs. By bridging the geographic divide between the two, Russia stands to gain by entering into a strategic and multifaceted partnership with South Korea that proves the seriousness of its Pacific Pivot and could potentially transform Northeast Asian affairs.

Mongolia’s Third Neighbor Policy

Mongolia has historically been in the Russian sphere of influence, but after 1991, the country spearheaded the so-called Third Neighbor Policy to diversify its relations in the post-Cold War world. This saw it reaching out in economic, political, and military (although largely benign) ways to distant partners such as the EU and NATO, as well as closer ones such as Japan and South Korea. The guiding philosophy behind this policy was that Mongolia did not want to be dominated by either Russia or China, the latter of which it secured its independence from in 1911 after centuries of control. This concept will be important in later understanding Mongolia’s anticipated role in bringing together Russia and South Korea.

Image: Although securing significant natural resource investment from leading Western companies such as Canada’s Ivanhoe Mines and the UK’s Rio Tinto, it still sells 90% of its natural wealth to China, creating just the type of dependency that it had earlier sought to avoid.

Mongolia’s Chinese Dependency

Mongolia has thus been faced with the dilemma of interacting with the wider world while still being dependent on its neighbors for physical trade networks. Although securing significant natural resource investment from leading Western companies such as Canada’s Ivanhoe Mines and the UK’s Rio Tinto, it still sells 90% of its natural wealth to China, creating just the type of dependency that it had earlier sought to avoid. The fact that 20% of Mongolia’s GDP is dependent on mining, and growth in this field has allowed the country’s GDP to be the world’s fastest growing since 2012 (and expected to remain among the top for the coming years), reinforces the dominant role that Chinese mineral purchases have on the overall Mongol economy.

King Coal and its Curse

There are concrete reasons why Mongolia’s mining sector (and consequently, the mainstay of its economy) became dependent on China. Way more than rare earth mineral demand (of which China is already dominant), this has to do with China’s insatiable appetite for coal. Bluntly put, Mongolia is nothing more than a raw resource appendage of China and has little purpose for Beijing besides helping to keep the lights on. Nonetheless, this arrangement was beneficial for Mongolia, so long as China kept buying coal.

At the same time, though, this may be rapidly changing in the near future. For the first time, China’s coal consumption has actually decreased by 23% year-on-year for August-September as the government implements cleaner energy policies and diversifies its electricity generation to natural gas and other means. Although ideal for China, this will be disastrous for Mongolia, seeing as how intricately its mining sector (and by degrees, its entire economy) is dependent on Chinese coal consumption. Whereas in the past coal was treated as a king in Ulaanbaatar, now it appears to be a curse, and the country desperately needs to diversify its consumer base to stave off economic destabilization and possible social and Color Revolution-influenced unrest.

Image: Mongolian train full of coal, heading to China. Mongolian mining sector (and by degrees, its entire economy) is dependent on Chinese coal consumption.

The Mongolian Middleman

As all of this is happening, larger global processes are at play. Russia has set a grand aim of becoming a Pacific Power and moving away from its previous European economic interdependence, and in light of recent East-West tensions and subsequent sanctioning, this has taken on a more pressing urgency than ever. Concurrently, South Korea, wedged between heavyweights China and Japan, is growing at a consistent rate and is on the prowl for energy resources to fuel this into the future. 97% of its energy is foreign-sourced, and its import of coal, already at 80 million tons a year, is expected to rise to 128 million by 2018. Thus, the situation is presented where Russia wants a more active East Asian presence, South Korea is thirsting for energy, and Mongolia has the world’s largest untapped coking coal deposit. It is through this confluence of factors that the three actors are uniting their interests, with Mongolia being the middleman via its Third Neighbor Policy, which allowed it to jointly develop positive relations with both Russia and South Korea and thus make the entire arrangement workable.

Russia’s Delicate Steps

Within this structure of interests, Russia took care to avoid upsetting its global strategic partner, China. It signed an historic natural gas deal in May to supply it with nearly half a trillion dollars’ worth of energy for 30 years, thus assisting with Beijing’s plans to replace coal with natural gas during this timeframe. This massively important tradeoff is advantageous for China and placates any fears or jealousy that it may have over Mongolia’s future trade links with South Korea. Additionally, Russia, China, and Mongolia have announced their intent to economically cooperate in a trilateral framework and create an economic corridor, showing that no bad blood exists between any of these actors. As is thus seen, Russia has taken delicate steps to ensure that Beijing would not be perturbed by its Mongolia-enabled outreach to South Korea, as such a move, in line with the practice of the Russian-Chinese Strategic Partnership, would increase the strategic influence of both Moscow and Beijing if successful.

The Way Forward

Going back to the Mongolia’s role in connecting Russia with South Korea, the heart of it all rests in a proposed railroad project to link Mongolia’s Gobi desert coal deposits to Russia’s Pacific coast. Afterwards, the coal would be loaded onto ships for transport to South Korea and possibly Japan. Leading Australian companies already fear that the opening of Mongolia’s coal resources to the East Asian market would be a game-changer and could possibly push them out of the market, indicating the enormous impact that this project would have if successfully implemented.

Although rail links already exist between Mongolia and China, as stated earlier, the former is trying to cut its future dependence on the latter and understands the additional influence that Beijing would have if the line ran southeast instead of northeast. Also of importance, Mongolia’s expected customers, South Korea and possibly Japan, would be hesitant to know that a growing percentage of their energy imports are indirectly controlled by China. That being said, the proposed railroad through Russia takes care to respect the geopolitical sensibilities of its intended East Asian client(s).

Russia’s Pacific Future

Projecting even further, the East Asian coal market is only one of the many spheres that would be fundamentally altered by the proposed Mongolian-Pacific railroad. One of the most breakthrough results of this would be the creation of a Russian-South Korean strategic partnership. Although Russia would be playing a physically passive role in the Mongol-South Korean energy relationship simply through allowing the railroad to traverse its territory, it will still have prized access to influential South Korean companies, investors, and government figures who are involved in its construction. As Russia naturally needs investment in its Far East and South Korea has a hunger for energy besides coal, this could open the prospect for South Korean investment in the region in exchange for Russian natural gas exports, most likely through LNG, of which Seoul is the world’s second-largest importer. Of relevant note, South Korea’s demand for natural gas is expected to increase 1.7% annually until 2035, meaning that both Russia and South Korea now have the perfect time to work out an energy deal as significant and historic as the one between Russia and China (possibly even involving the promise of a share of Artic gas resources in the future).

The strategic partnership between the two states would then take on a larger significance. The demonstration effect of the booming Russian-South Korean energy trade could possibly convince recalcitrant Japan to abandon its blind loyalty to its American overseer and concede its Kuril Islands claims in exchange for a similar and much-needed deal as well. Additionally, South Korea is at the center of the US-China-Japan nexus in Northeast Asia, and by moving closer to Russia, it can expand its foreign policy importance and serve as the perfect conduit between all four actors in this region. By integrating Russia more closely into the region and its affairs, it could give it a greater stake in the peninsula’s future, thereby possibly motivating it to seek a diplomatic breakthrough in the North Korean nuclear talks. With Russia returning to the Korean peninsula, no matter in which form this takes (diplomatic, energy, political, economic, etc.), it would place the US on the strategic defensive in Northeast Asia and show that Russia has succeeded in pivoting to the Pacific.

Concluding Thoughts

It is of absolute importance for Russia’s future that the country move as rapidly as possible to the burgeoning Asia-Pacific region. Although China is a steadfast and loyal strategic ally, by itself, bilateral relations between the two do not constitute a proper Pacific Pivot for Russia. Instead, what is urgently needed is for Russia to enter into a strategic relationship with a non-Chinese partner that can immediately accelerate full-spectrum relations between the two. This is where South Korea comes in, but the key to accessing that country’s decision makers and business leaders is to provide them with something that they too urgently need, and this is Mongolian coal. By acting as a conduit between Mongolia’s coal mines and South Korea’s power plants via a strategic railroad, Russia can take a concrete step in pivoting to the Pacific, attracting investment to the Far East, and working to transform the long-term nature of Northeast Asian relations.

Andrew Korybko is the American political correspondent of Voice of Russia who currently lives and studies in Moscow, exclusively for ORIENTAL REVIEW.