Militarization and The Trans-Pacific “Strategic Economic” Partnership

A Secret Deal Negotiated behind Closed Doors

At present, there are two little words left dangling off the title of a free-trade agreement that the U.S. has been involved with negotiating since 2009. The Trans-Pacific “Strategic Economic” Partnership Agreement, or what we generally call the TPP, has been mostly framed as a secret free-trade agreement that is being advised by 600 of the largest corporations undermining government regulations on the environment, labor, finance and other regulatory industries; a 21st-century neoliberal assault that aims to streamline the global supply chain and undermine the sovereign integrity of states.

What has received less attention is that this strategic economic partnership has in large part, taken the form of a policy initiative called the Pacific Pivot, a shifting of military resources into the Pacific.

The TPP was originally considered a pathfinder agreement for a Free Trade Area of the Asia Pacific (FTAAP) which grew out of APEC, and was signed in 2005 between Singapore, NZ , Chile, and Brunei. Officially, the U.S. agreed to enter talks with the TPP countries on the liberalization of trade in the financial services sector in January 2008, and the following September, U.S. Trade Representative Susan Schwab announced that the U.S. would negotiate entry. In November 2009, Obama officially confirmed membership with the new expanded TPP partners and the U.S. launched negotiations “with the goal of shaping a regional agreement that will have broad-based membership and the high standards worthy of a 21st century trade agreement.”

In a November 2009 speech Obama gave while in Tokyo, he said, “the growth of multilateral organizations can advance the security and prosperity of this region. I know that the United States has been disengaged from many of these organizations in recent years. So let me be clear: Those days have passed. As a Asia Pacific nation, the United States expects to be involved in the discussions that shape the future of this region, and to participate fully in appropriate organizations as they are established and evolve.”

For context, agreements to enter TPP talks occurred before the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy in mid-September of 2008 ignited the economic collapse of our financial sector. Within days, CEOs of many of the top U.S. corporations who lost their short-term investments with Lehman’s collapse threatened Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson of walking away from their posts unless the federal government bailed them out. A walk-out by the CEOs of the top fast-food and retail business chains would threaten the government of having to react to unprecedented unemployment. It was clear that if CEOs did not receive a bail out, a large percentage of the 99% who live off their service-sector jobs would suddenly stop receiving paychecks. On Oct. 1st, President Bush signed the $700 billion dollars Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP). By March of 2009, within months of Obama’s presidency, the Federal Reserve committed $7.77 trillion dollars to rescue the financial system. When Obama won the presidency he not only inherited the financial collapse, but the TPP as well. Let that sink in for a minute.

By 2011, the Trans Pacific Strategic Economic Partnership had expanded to nine countries, and at the APEC meeting in Hawaii, it was announced that Canada and Mexico were joining and most suspected that it was just a matter of time before Japan would join talks.

Today, with it’s current 12-nation membership, the combined GDP of TPP countries is more that $26 trillion dollars, representing over a third of global GDP.

During APEC 2011, Obama unveiled his Pacific Pivot, a shifting of 60% of U.S. military resources from Iraq and Afghanistan, from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The policy was addressed by Hillary Clinton in a Foreign Policy op-ed a month earlier, called “America’s Pacific Century,” in which she outlined a six-point plan. These include: 1) strengthening bilateral security alliances; 2) deepening our working relationship with emerging powers; 3) engaging with regional multilateral institutions; 4) expanding trade and investment; 5) forging a broad-based military presence; and 6) advancing democracy and human rights.

Further, Clinton described the progress of the TPP as bringing coherence to the U.S. regulatory system and the “efiiciency of supply chains,” and hopes that the TPP agreement will eventually form the regional interaction of an FTAAP.

National Security adviser Tom Donilon said, “the shift in focus toward the Asia-Pacific region isn’t just a matter of military presence. Rather, he added, it’s an effort to harness all elements of U.S. power: military, political, trade and investment, development and values.”

NATO too, has refocused its attention to the Pacific, emphasizing a reliance upon U.S. maritime security. Even as recently as the August 2013 issue of “Atlantic Voices,” the Atlantic Treaty Association’s Journal analyst Miha Hribernik highlights key areas of cooperation between NATO and the Asia Pacific. In the Path Ahead for NATO Partners in the Asia-Pacific, he writes, “The North Korean threat or the unpredictable Sino-Japanese stand-off over the Diaoyu/Senkaku Islands could even entangle NATO directly. In the event of escalation and US involvement, Washington could possibly invoke Article 4 – or even Article 5 – of the North Atlantic Treaty and involve the other 27 allied countries. For all intents and purposes, NATO has one foot in the Pacific at any given time.”

Since the announcement of the U.S. joining the TPP, the U.S. has been in the midst of aligning new partnerships in the Pacific. In 2010, I posted an article here called “Clinton and the Colonial Paradigm” which outlined the 6-point military/strategic alliance that the U.S. had been forming in the Pacific with partners that include the Pacific Island Forum. This alliance includes the cooperation of Pacific Island partners in the assertion of the “Pacific Plan,” a regional development and investment proposal asserted by the Pacific Island Forum. Whether it was intended to or not, the Pacific Plan serves as the latest blueprint for colonial hegemony facilitated by Obama’s announcement of a “Pacific Pivot.”

“STRATEGIC”

I want to briefly address this word “strategic,” as it is often elusive like a Chesire Cat, sometimes visible sometimes not. “Strategic” is an example of a word that has a very precise meaning in the context of international agreements, yet it is often overlooked. The Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of Marshall Islands, and the Republic of Palau comprise the Freely Associated States (FAS). They were originally listed as Trust Territories, territories that had belonged to the Axis power in WWII, to be administered for decolonization along with the other Allied held, Non-Self-Governing Territories. In 1947, the FAS were reclassified as a United Nations Strategic Trust Territory to be administered by the United States. Although they should have been afforded the same rights for self-determination as the other 62 countries that gained their independence as a result of the UN decolonization process, their sovereignty was limited because of the insertion of that little word “strategic.” Despite its often glaring omission in the FAS’s designation as Trust Territories, the U.S. had taken up military stewardship over the strategic role of “protecting the inhabitants against the loss of their lands and resources.”

“ECONOMIC COOPERATION”

As an FTAAP, the TPP was meant to be a potentially APEC-wide free-trade agreement. APEC, the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation has often been described as “four adjectives in search of a noun.” However, the term “economic cooperation,” much like “strategic” has a very precise meaning, too. The 1948 Economic Cooperation Act (ECA), aka the “Marshall Plan” was as much a military and strategic international agreement as it was a development/aid and investment strategy. The ECA provided development and aid to war torn Europe in exchange for its commitment to US-free market trade rules, which is arguably the rod that pulled the Iron Curtain of the Cold War. The USSR was working off an entirely different development and economic stabilization model that was “inter-dependent” of states trading resources to build their own infrastructure and labor programs towards full-employment.

“Economic Cooperation” became the moniker in International Organization-speak for a post-war U.S. economic strategy that aimed to centralize free-market development and trade among cooperating countries and their territories. The Economic Cooperation Act harmonized branches of the State Department, the various bureaus within the Departments of Labor, Commerce, and Agriculture, the Treasury, the Washington Import-Export Bank, and created an entirely new international union called the International Confederation of Free-Trade Unions. The stated purpose of harmonizing these departments were to conform to changes motivated by the creation of the United Nations while protecting commercial interests. In terms of development and aid, this meant rebuilding Europe’s infrastructure with a sizable quota of U.S. labor, while providing participating countries with development funds for small and medium-sized businesses. This aid was provided in exchange for cooperating with a list of fundamental reforms in currency, trade, shipping and banking rules. Additionally, these reforms also included more open access to the commodity resources of the economic cooperation’s old territories (most of which were listed as non-self-governing territories in accordance with Chapter 11 of the UN Charter).

By 1951, the ECA was renamed the Mutual Security Act, which continued to provide the framework for US military involvement over the role of “promoting the foreign policy of the United States by authorizing military, economic and technical assistance to friendly countries, to strengthen the mutual security and individual and collective defenses of the free world, to develop their resources in the interest of their security and independence and the national interest of the United States and to facilitate the effective participation of those countries in the United Nations system for collective security.”

Russia, after rejecting economic cooperation in 1948, joined APEC in 1998, seven years after the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

THE TPP IS A STRATEGIC AGREEMENT

The TPP is a strategic agreement between the United States, Vietnam, Malaysia, Singapore, Brunei, Mexico, Peru, Chile, Canada, Australia, NZ, and Japan. There is no Soviet threat, and no Russian participation in the TPP. Also missing from the TPP is China, the second largest economy in the world, and it’s absence reflects the TPP’s move away from its originally designed FTAAP. For the US, China’s rise is perceived as a threat to its global economic hegemony, and unless the US is able to contain China’s economy, the TPP serves as a kind of China containment strategy.

Despite rising tensions over disputed maritime boundaries in what is conventionally considered the South China Sea, the catalyst for this threat over Chinese military aggression is, rather, the Chinese investment process. China’s system of State-owned investment (SOI) has won them favor in the Africa, Middle East, Pacific, Caribbean, and Central/South America regions, in many of the same resource-rich countries that the U.S. and its allies struggled to control during the post-war years.

Currently, neither the US nor the EU have the regulatory means or authority to stop competing Chinese investment protocols, however, the new EU-US Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) may try to develop new investment and trade rules allowing for a greater capacity to compete with China over the investment of the commodity resources in developing countries.

BRICS

One of the result’s of China’s economic success in negotiating regional and global trade is that China has the economic clout to partner with other ex-colonial or non-ECA partners, Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa to potentially give rise to a new currency reserve based on what Goldman Sachs termed BRICS.

One of the result’s of China’s economic success in negotiating regional and global trade is that China has the economic clout to partner with other ex-colonial or non-ECA partners, Brazil, Russia, India and South Africa to potentially give rise to a new currency reserve based on what Goldman Sachs termed BRICS.

A reserve currency stabilizes currencies in participating markets and provides greater access for trade. Without a stabilizing currency, trade in the global market would be extremely slow and cumbersome, particularly since every currency and commodity trade has to be valued against the perpetual fluctuations of a basket of unstable markets.

The standard economic indicator that is used to measure the strength of our national economies for trade is GDP, a national accounting system that was defined by the U.S. in 1953 and has been revised via the UN System of National Accounts in 1993 and in 2008. How we account for GDP is the index through which we measure national economies and the value of our currencies in trade.

(For those who seek clarity over the accounting framework, this may be a good time to address an article that I posted on the UN SNA and the 2008 accounting revisions, including the way the accounting of military systems were revised, as it is well-referenced with a lot of primary documents.)

The rise of the BRICS as a competing reserve currency is technically what the IMF calls, Special Drawing Rights (SDR) and the role of a BRICS SDR would be to stabilize fluctuating currencies among the emerging or developing trade partners. From the perspective of the dominant US and the EU economies, the rise of BRICS is both in direct competition and symbiotic to the reserve currency held by the US Treasury, which not coincidentally, was also a process that resulted from the Economic Cooperation Act.

What the move towards BRICS means for developing economies is that it is a viable alternative to the World Bank, the Asia Development Bank, and other global financial institutions that demand structured repayment of their loans and investments for the development of infrastructure services facilitating, for example, resource acquisition and extraction industries. As is evident, the turnaround time for the development of infrastructure projects don’t often fall into the time frame or profit margins demanded by investment banks, and China and the state-owned investment banks are able to restructure debt payments in a way that doesn’t criminalize governments and peoples, as it did with Greece, which perhaps coincidentally, was the first country to receive post-war security and development assistance. The 1947 “Bill to provide assistance to Greece and Turkey Act,” was the direct precursor to the establishment of the 1948 Economic Cooperation Act.

In July of 2012, the World Bank launched a program to raise $400 billion dollars to finance development needs through a global tax reform. Primarily targeting the top transnational corporations, it appears that this global tax reform is being harmonized in coordination with a wide range of global governance reforms and new international programs that reaches towards meeting the 2015 UN Millennium Development Goals, addressing economic and environmental reform, poverty reduction and other development needs. If there is an agenda to harmonize these global governance reforms, then arguably, the rush to conclude the TPP/TTIP at its present timetable seeks to use the combined economic weight of the U.S. cooperation as leverage to assert its influence and role in reforming global markets.

To be clear, I don’t want to suggest that these global governance reforms are directed towards containing China or BRICS, but I do think that the interests of the large transnationals and extractive industries are lobbying for governments to ensure that any new revision to global governance is designed to meet the demands of industries.

As recently as last September for example, the final declaration from the G20 summit reaffirmed their support for the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), a tax and trade initiative comprised of the industrial mining and mineral sector.

Although many rightfully take issue with calling China a containment strategy in the way we might talk about containing North Korea, I’d suggest that what we are actually seeing is more of a containerment strategy. For one thing, as long as China’s relationships with their trade partners remain productive, China is beyond being contained and any attempt at containing China would likely be seen as a deluded conceit.

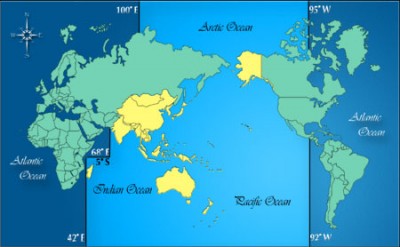

There are, however, other strategies that could be employed that can impede China’s transport of materials, resources and manufactured goods, and one of those is controlling the shipping lanes. As long as the US maintains the transpacific partnerships, the US will continue patrolling and assisting to militarize the shipping lanes. As the image to the left shows, China’s container traffic (in yellow) measures 5000+ transits a year exceeding 10,000 gross tonnage per ship, or 13+ transits a day.

As BRICS economies become the favored trade partner with many of the developing resource-rich countries, and with China being the manufacturing powerhouse that it is, how does the US and EU maintain their influence when their investment procedures have become outmoded? BRICS has a procedural, if not fraternal advantage over the US/EU, and the rise of the BRICS economies will likely attract further partnerships among the developing countries.

Revisiting the old colonial power’s administrative strategy which has been employed for centuries, the U.S. appears to be further militarizing the shipping lanes in accordance with today’s customary international maritime law. Of course innocent passage through territorial seas is a right of nations, however, there are a wide range of U.S. laws and new treaty obligations pertaining to fisheries, wildlife, customs, immigration, environmental protection, marine safety that are enforced by regional or national agencies and could be used to involve the Department of Defense, not to mention the transport of illegal substances and weapons, which would directly involve the military.

In preparation for the writing of this article, I read through the Annotated Supplement to the Commander’s Handbook on the Law of Naval Operations, Oceans Law and Policy to get a sense of the procedures with which ships could be detained in the territorial waters of cooperating countries. Without overreaching, the U.S could– within the reach of international law– control the passage of ships through territorial waters while employing a program of peaceful transit passage. This is equivalent to putting up stoplights on freeways or highways and allowing the police to randomly search your vehicle.

A July 2013 incident that underscores the control that is manifest within the right of innocent passage, is that a ship delivering sugar from Cuba to North Korea was stopped at the Panama Canal for suspicion of drugs. Authorities found undeclared weapons hidden in the cargo and the ship was detained for inspection. In a statement from Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, officials said the vessel was carrying “240 metric tons of obsolete defensive weapons… all of it manufactured in the mid-20th century — to be repaired and returned to Cuba.”

What was strange was that the timing of this seizure occurred just days after Nicaragua announced that it had signed that investment deal by a Chinese billionaire, to build a Nicaraguan canal that would essentially open the Asia-Pacific with the Caribbean and its Atlantic-American trade partners, via Nicaragua’s maritime boundaries and outside the jurisdiction of the U.S. military. It has been put forward by some reports that the Chinese government is behind this investment deal.

DIRE STRAITS

Regional free-trade agreements and other bilateral trade agreements are pathways through which we could impose our strategic economic influence and destabilization policies, encouraging public consent of US maritime security in the region.

If we map out China’s main transport route for importing resources from Africa, the Middle East, Russia, and the Pacific, and we impose the militarized areas of multi-laterel or bilateral FTA or Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) countries, the first thing that we notice is that these are mostly militarized choke points that have become unstable since the signing of these agreements.

If we map out China’s main transport route for importing resources from Africa, the Middle East, Russia, and the Pacific, and we impose the militarized areas of multi-laterel or bilateral FTA or Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) countries, the first thing that we notice is that these are mostly militarized choke points that have become unstable since the signing of these agreements.

• The Strait of Malacca which is part of Malaysia/Singapore and the access route for China to the Middle East and Africa already had a strong presence via COMLOG WESTPAC; and was established at the Port of Singapore Authority after it relocated from Subic Bay, Philippines, when the base was closed in 1992.

• The Spratly Islands are 45 islands occupied by military forces of China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Brunei. Besides China, all of the countries with a claim in the Spratly Islands are TPP countries, or have, in the case of the Philippines a TIFA with the U.S. Despite these overlapping territorial claims, the Association of Southeast Asian Countries (ASEAN) have been at the forefront negotiating a resolve over these long-held historical disputes.

ASEAN is also a regional forum of which the U.S. attends but is not a member and China and ASEAN members have begun negotiations over what can be seen as a competing trade alignment to the TPP, the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). Whichever agreement concludes first will establish the rules of trade in the region, and just as China will be free to join the TPP if it adopts and conforms to US-led rules, the U.S. too will be free to join the expanded ASEAN+, if the RCEP should conclude first. Neither China nor the US will be excluded from the TPP or the RCEP once concluded. At the moment, I’d argue, the race is over investment and trade rules.

• Jeju, aka “Peace Island” is a pristine island belonging to South Korea and is at the nose of the Korea strait leading from the South China Sea to the East Sea or the Sea of Japan. The militarization of Jeju by the ROK in 2011 has been controversial because it is a multiple UNESCO World Heritage Site, a major tourist attraction and has been a symbol of Peace following the slaughter of up to 80,000 civilians by ROK troops during a democratic uprising in 1948. It should not be thought of as merely coincidence that the militarization of Jeju was announced after the KORUS FTA was signed in 2007, and just after the conclusion of new agreements in 2010.

• Jeju, aka “Peace Island” is a pristine island belonging to South Korea and is at the nose of the Korea strait leading from the South China Sea to the East Sea or the Sea of Japan. The militarization of Jeju by the ROK in 2011 has been controversial because it is a multiple UNESCO World Heritage Site, a major tourist attraction and has been a symbol of Peace following the slaughter of up to 80,000 civilians by ROK troops during a democratic uprising in 1948. It should not be thought of as merely coincidence that the militarization of Jeju was announced after the KORUS FTA was signed in 2007, and just after the conclusion of new agreements in 2010.

On March 26, 2010, forty-six South Korean sailors were killed in an explosion that sank the Cheonan, a South Korean Pohang-class corvette of the Republic of Korea Navy (ROKN). An international team of investigators, which excluded both China and Russia, concluded that the fragments of the torpedo which was said to have sank the Cheonan was North Korean. At the time of this sinking, the US and the ROKN were in the midst of one of the largest and longest running wargames, Key Resolve-Foal Eagle. The controversy over who sank the Cheonan has not been resolved, particularly since accusations of a North Korean sub infiltrating South Korean waters during these war games and escaping have been largely dismissed by critics and independent observers. However, the effect of this tragedy was enough for President Lee to stir Koreans into supporting further militarization.

How Jeju conforms to the China “containerment” theory, is that commodity resources are also being shipped from Vladivostok, and a new port on the North Korean side of the Tumen river where China, Russia and North Korea share borders. China and Russia have just signed leases allowing them access to the new North Korean harbor which is said to be a very deep and fast port, and unlike Vladivostok, it is open year round and not susceptible to closures because of ice.

• The Senkaku/Daioyu Island dispute. In Sept. 2012, the Japanese government reached an agreement with the family that owns three of the five islands in the disputed Senkaku/Daioyu chain to purchase the territory for Japan. The Senkaku islands, between Okinawa and Taiwan, also lie along the shipping lanes near China’s manufacturing corridor along the East China Sea. When China protested, Prime Minister Noda hinted at using Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (SDF) to “defend” Senkaku if China responded militarily. According to a recent Japan Times article, the Japanese government consulted with the State Department prior to the purchase, and the U.S. State Department had given “very strong advice not to go in this direction.”

• The Senkaku/Daioyu Island dispute. In Sept. 2012, the Japanese government reached an agreement with the family that owns three of the five islands in the disputed Senkaku/Daioyu chain to purchase the territory for Japan. The Senkaku islands, between Okinawa and Taiwan, also lie along the shipping lanes near China’s manufacturing corridor along the East China Sea. When China protested, Prime Minister Noda hinted at using Japan’s Self-Defense Forces (SDF) to “defend” Senkaku if China responded militarily. According to a recent Japan Times article, the Japanese government consulted with the State Department prior to the purchase, and the U.S. State Department had given “very strong advice not to go in this direction.”

Following this action, nationalist protests erupted in both Japan and China. Discussions about expanding the role of Japan’s SDF, including the redrafting of Article 9, which prohibits Japan from possessing military power were held, and as of October 3, 2013, Japan and the U.S. concluded a joint statement implementing military cooperation meeting Japan’s regional military objectives.

From a July 2012 article in Asia Security Watch, “Japan’s Regional Security Environment and Possibilities for Conflict:”

“Indeed there are signs of a strategy being implemented. While Noda is unlikely to decisively agree to Japan’s joining TPP negotiations, he will continue to fly the TPP flag”… “and the LDP have identified in their policy statements a desire to change Japan’s disposition towards defense and collective self-defense in particular, the dubious mechanism of “constitutional reinterpretation” to Article 9. Noda has in the last week identified discussion on the interpretation of collective self-defense as something he wants to push forward in the current parliamentary session, particularly as it pertains to defense of US ships on the high seas and Japan’s use of its BMD system to defend the US from ballistic missile attack. Finally, Noda has also pushed forward on the previously identified proposal of ‘nationalizing’ the Senkaku Islands… “

Japan had been teetering on the TPP fence, since the U.S. announced it was joining talks. Japan’s powerful agriculture lobby was adamantly opposed to Japan joining the TPP, understanding that any agreement would threaten government protections of rice and small family rice farmers, the backbone of Japanese agriculture. However, the TPP had very wide support among the business and commerce, manufacturing and automobile sectors and this was reflected by the conservative Liberal Democratic Party win of both the Upper and Lower house of the Japanese Diet.

Despite the shroud of secrecy that continues to enfold TPP negotiations, when it came to Japan, every nuance had been magnified. For many following the TPP as closely as we’ve been able to over the last few years, the question of whether Japan would join or not would unfold how the TPP would conclude, if at all.

Because of the size and influence of the Japanese economy, some thought that Japan joining would end up stalling the negotiations, others thought Japan joining would ensure quick conclusion, either way, it was anticipated that with Japan’s entry, new concessions and demands would have to be met, and this would include US-Japan Defense Cooperation.

When the Oct. 3rd high-level US-Japan Security Consultative Committee met in Tokyo, new bilateral planning over the sharing of defense technology and facilities were established, strengthening Japan’s SDF, integrating Japan in “multilateral cooperation” in trade, maritime security, disaster relief and trilateral cooperation between Australia and the ROK, and realigning U.S. forces in Japan.

In a private meeting with Ho-Fung Hung a Chinese political economist and featured speaker at the Feb. 2011, USC “State of the Chinese Economy” conference about China’s relationship to the TPP, Hung expressed, “at this time, China did not take an official position because it was waiting to see what Japan does, whether or not Japan signs on to the TPP or not.”

Two years later, Hung’s analysis appears to have rung true. On March 16th, 2013, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, formally announce that Japan would join the TPP. What followed is that in May, two months later, China’s alternative to the TPP, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) held it’s first meeting in Brunei with ASEAN+6 members (which include Australia, Japan, South Korea, India and New Zealand). In June, Hong Kong billionaire, Wang Jing, signed the inter-oceanic Nicaragua canal investment deal with Nicaragua president Daniel Ortega to develop a $40 billion project in the U.S. hemisphere. And on July 23rd, Japan officially became the 12th member of the TPP.

Now I don’t want to over-determine the narrative of these events, because history never really unfolds this neatly. I do however, want to assert that Japan has been a lynchpin to US-China relations and much of what happens now between the US and China across the Asia-Pacific region will result from Japan having joined the TPP. If the dots were not already connected, this US-Japan security alliance was predicated on Japan joining the TPP (or vice-versa).

This is the TPP

So as part of the justification for this Pacific Pivot, could it be that the US has been quietly emboldening our Trans Pacific Partners and other FTA or TIFA allies into manufacturing tensions? In looking at the timeline of events, it would be difficult to disassociate the U.S. backed militarization of the Pacific Pivot from being distinctly separate from the policy of economic cooperation.

These manufactured events, as Noam Chomsky describes in Manufacturing Consent, are “related to the understanding that indoctrination is the essence of propaganda. In a “democratic” society indoctrination occurs when the techniques of control of a propaganda model are imposed — which means imposing Necessary Illusions.” In this case the necessary illusion is economic cooperation.

We cannot, should not separate the TPP from its military component. It’s disingenuous to call for an end to these free-trade agreements without simultaneously calling for an end to militarization.