History: Britain’s Complicity in 1953 Iranian Coup Revealed: The Smoking Gun, MI6’s “Man of Mystery”

Must-See New Documentary Exposes Britain’s Complicity in the 1953 Bloody Coup in Iran–A Collusion which the UK Continues to Officially Deny After 67 Years

After 60 years of foot-dragging and dissembling, the U.S. government finally confessed and admitted its role in the bloody 1953 coup that overthrew Iran’s democratically elected government led by Dr. Mohammed Mossadegh. With Coup 53’s compelling documentary evidence, its now Britain’s turn to fess up.

More than 300 were killed and thousands imprisoned for “treason” in an MI6/CIA-backed coup that left the country condemned to a 25-year reign of terror under the dictatorship of U.S.-backed Shah, Mohmmad Reza Pahlevi.

In 2013, the CIA officially fessed up and admitted to (1) bribing high Iranian government officials, (2) spreading defamatory anti-government propaganda, (3) hiring Tehran’s most brutal criminal gangs to riot in the streets and ultimately (4) orchestrating the 1953 coup d’état in Iran as an act of U.S. foreign policy planned and approved by the highest levels of government.

But not a peep from Great Britain—which admitted nothing and concealed everything. The British government may even have arranged to conceal an interview with a talkative MI6 spy named Norman Darbyshire, who actually revealed his—and Britain’s—complicity in the Iranian coup during a 1985 BBC documentary called End of Empire. But his incriminating testimony was mysteriously edited out of the broadcast before it aired.

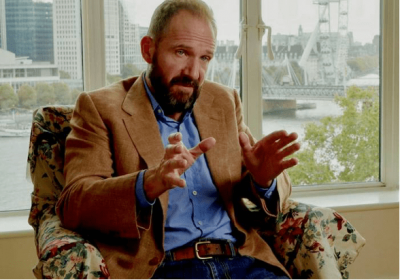

However, the transcript of agent Darbyshire’s lost interview has now resurfaced in numerous independent locations and has been reenacted, prominently, in this new documentary.[1]

The film’s director Taghi Amirani, an Iranian who traveled around the world seeking new details about the coup that devastated his homeland, stated:

Even though it has been an open secret for decades, the UK government has not officially admitted its fundamental role in the coup. Finding the Darbyshire transcript is like finding the smoking gun. It is a historic discovery.[2]

What Agent Darbyshire Reveals

Darbyshire served as head of the MI6’s Persian division based in Cyprus and worked in Iran from 1943 to 1947 and then again from 1949 until he was kicked out by Mossadegh in 1952. His motive for granting the interview to the BBC appears to have been to counter the boastful claims of CIA agent Kermit Roosevelt who wanted to take credit for the coup. In the all-important interview, Darbyshire stated his belief that Mossadegh was a weak character, an ardent nationalist and xenophobe who would have soon been overwhelmed by the communists if the British had not stepped in.

From the beginning of his time in the country, Darbyshire said he had been under orders from the British Foreign Secretary to remove Mossadegh secretly without telling the ambassador. He wanted to enact the coup earlier, but the head of the British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), John Sinclair, knew “about as much of the Middle East as a ten year old and was far more interested in cricket anyways.”

Darbyshire went on to detail that he had carried biscuit tins with “damn great notes” to pay bribes and that the coup operation cost around 700,000 pounds, a total he would know because “[he] spent it.” The coup plot, he also said, “worked.”

Darbyshire said that he played an especially key role in enlisting the Shah’s Sister, Princess Ashraf, who was tracked down in Paris and paid to go to Tehran to convince her brother to go along with the coup.

Darbyshire and his associates further paid off organized criminal networks led by the Rashidian Brothers, whom he said were “intrigued by contact with the British and delighted to take our money for something they believed in themselves.”

As the documentary shows, the MI6, in collaboration with the CIA, (1) planted anti-Mossadegh propaganda in the media, (2) recruited mobs to riot and chant anti-Mossadegh slogans, (3) bribed members of Iran’s parliament, and (4) assassinated key figures who were loyal to Mossadegh, most notably the head of the national police, Mohammed Afshartous.

Darbyshire notes in his interview that MI6 did not intend to kill Afshartous, only to kidnap him. According to Darbyshire:

Something went wrong: [Afshartous] was kidnapped and held in a cave. Feelings ran very high and Afshartous was unwise enough to make derogatory comments about the Shah. He was under guard by a young army officer and the young officer pulled out a gun and shot him. That was never part of our program at all but that’s how it happened.

However, this does not explain the clear evidence of torture on the body, not to mention that the corps was dumped on the street for all to see—a technique that is often used to instill widespread fear.

The rogue, young army assassination story is thus suspect, especially given men like Darbyshire; they are experts in disinformation. Their job is to cover up their agencies’ crimes, smear their enemies and try to sanitize the historical record—even after their own passing, as Darbyshire died in 1993.

Mohammed Mossadegh on trial after the coup. [Source: batiraporu.com]

Devious Policies

While Darbyshire may be trying to hoodwink us one final time, Coup 53 is nonetheless a remarkable film because of the many interviews that it runs, not only with Darbyshire, but also with other CIA and British MI6 operatives who speak openly about the people they were dealing with and the devious policies they were enacting in Iran.

Sir Peter Ramsbotham, for example—a man who would later become Ambassador to Iran in the early 1970s—revealingly discusses how the men on her Majesty’s Middle Eastern desk would call Mossadegh “dotty” or crazy in the head because of his defiant policies and habit of conducting bedside conferences in his pajamas.

A strong parallel exists with Belgian secret service agents who branded Patrice Lumumba, Congo’s first post-independence leader, as “Satan” after he had condemned Belgian colonialism and aimed to assert national control over the Congo’s rich mineral wealth.[3]

In a CBC documentary made in the 1990s, Colonel Louis Marlière and former CIA Station Chief Lawrence Devlin cavalierly discuss the different methods they had adopted for trying to assassinate Lumumba, including the use of toothpaste poison, and how Lumumba’s body was disposed of in acid.

When asked about his reaction to Lumumba’s killing in January 1961, Colonel Marlière said “good riddance,” while Devlin stated that he had been very busy, and with Lumumba out of the way, a major problem had been solved.

Lumumba (center), prior to his murder by firing squad, had much in common with Mossadegh, both in terms of his domestic policy and in the way he was overthrown. [Source: trtworld.com]

Colonial Legacy

Coup 53 significantly showcases the colonial conditions that existed in Iran prior to the coup, which were similar to the Congo and other African countries.

The British expatriates lived in luxury while the locals were treated as second-class citizens or worse in their own country. An old Iranian gardener interviewed in the film describes commuting from his mud hut to the show-piece cottages with backyard swimming pools that were advertised in promotional videos by the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company trying to recruit new British employees.

The Iranians who worked for the Anglo-Iranian Company did not mix with the British who called them wogs. Further tensions developed when the British built a pipeline to Iraq, under the Koran River, as a means of siphoning off fuel for the British Royal Navy.

While the Anglo-Iranian oil company had rights to drill for oil in Iran, the agreement entailed paying Iran 16% of the revenues in return. When requests to see the company books were rejected, the Iranian government decided to nationalize the oil refineries.

Darbyshire himself acknowledged that the Iranians, “had the feeling they were being screwed the whole time and quite rightly too and from about 1920 onwards.”

After Mossadegh’s nationalization decree, the British tried to destabilize the government by sabotaging the major oil refinery at Abadan and prevent it from working.

U.S. President Harry S. Truman at the time enjoyed positive relations with Mossadegh who was named as Time Magazine’s Man of the Year in 1952, and rebuffed British overtures to back a coup.

However, when Truman was succeeded by Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, and foreign policy was placed under the control of John Foster and Allen Dulles, who had worked for one of Wall Street’s biggest financial houses, Sullivan & Cromwell, Mossadegh’s political fate was sealed along with that of the Iranian people.

Final Moments of Coup Reenacted

The interviews in Coup 53 vividly recount the final moments of the coup and the heroism of those who tried to defend the sitting president. Mossadegh’s relatives, former bodyguards and aides testify about Mossadegh’s despondency after the coup, exacerbated by his solitary confinement and subsequent house arrest.

Mossadegh generally comes across sympathetically as an intelligent and dignified leader who had the best interests of his people in mind. By contrast, the coup plotters, like Colonel Marlière, come across as smug and arrogant, showing little remorse for their coordination of the sinister plot.

Anti-Mossadegh protestors on eve of the coup display a portrait of the Shah. [Source: theguardian.com]

The Iranian coup ultimately poisoned U.S. and Western relations with the Middle East and signified that the West, while favoring authoritarianism, would overthrow democratic regimes which sought to control and more equitably distribute their own economic resources.

One can indeed trace an important lineage between the 1953 coup in Iran and the 1954 coup in Guatemala right on up through to recent efforts by the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) and other U.S. government agencies working in collaboration with the British to try to topple left-wing and nationalistic regimes that tried to enact similar policies to those in Iran led by Mossadegh.

Darbyshire tellingly returned to Iran in the early 1960s where he played a role in developing the Shah’s secret police, SAVAK, which was notorious for torturing and terrorizing the political opposition. His career and legacy remind us of the damaging consequences of covert operations and the need for transparency in government.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Jeremy Kuzmarov is Managing Editor of Covert Action Magazine and author of four books on U.S. foreign policy, including Obama’s Unending Wars (Clarity Press, 2019) and The Russians Are Coming, Again, with John Marciano (Monthly Review Press, 2018).

Notes

[1] Coup 1953 (2020), Taghi Amirani, Walter Murch, https://coup53.com/. The National Security Archive has reprinted the Darbyshire interview on its web site: https://nsarchive.gwu.edu/dc.html?doc=7033886-National-Security-Archive

[2] Julian Borger, “British Spy’s Account Sheds Light on Role in 1953 Iranian Coup,” The Guardian, August 17, 2020, https://www.msn.com/en-

us/news/world/british-spys-account-sheds-light-on-role-in-1953-iranian-coup/ar-BB182WX0

[3] Lumumba’s adversary, the Belgian collaborator Moise Tshombe, was nicknamed “the Jew” because he governed the wealthy province of Katanga.

Featured image: As reenacted in the new documentary entitled “Coup 53,” British MI6 agent Norman Darbyshire reveals all the dirty details in suppressed interview. [Source: ft.com]